The middle of April strikes dread (or joy) in the hearts of millions of tax filers. Since 1955, April 15 has typically marked the end of the tax season in the continental US. This year, however, filers have received a three-day reprieve to accommodate Emancipation Day in Washington D.C, which is observed on the weekday closest to April 16 when it falls on a weekend.

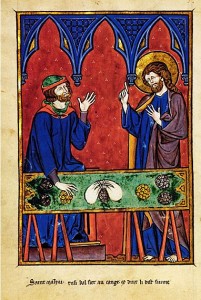

Saint Matthew is among the best-known tax collectors in the history of Christian art. According to the gospel accounts, Jesus encountered Levi (Matthew’s name before his conversion) in the custom house of Capernaum on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. Jesus said to him, “Follow me,” and Matthew obeyed.

A remarkable depiction of Christ calling Matthew appears in the Picture Book of Madame Marie, a thirteenth–century French devotional manuscript now at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. The scene takes place beneath sharply-cusped arches and against a fiery background. Wearing a brilliant blue garment and purple cloak, Christ addresses Matthew, whose money table has been dramatically tilted to reveal neat piles of gold and silver coins. Thematically related is a fifth-century gold solidus of Pulcheria with the empress wearing an elaborate coiffure and lavish jewels, a macabre Dance of Death featuring a money-changer from a fifteenth century French Book of Hours, and a regal image of the Queen of Coins on a fifteenth-century Italian tarot card.

May the rocks in your field turn to gold!

“And when he was come into Jerusalem, the whole city was moved, saying: Who is this? And the people said: This is Jesus the prophet, from Nazareth of Galilee.” (Matthew 21:10-11)

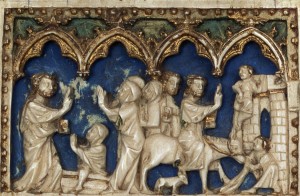

Celebrated seven days before Easter Sunday, Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Passion Week and commemorates Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The episode, which appears in the four canonical gospels, describes the multitudes gathering at the gates of Jerusalem to welcome Jesus, laying their cloaks and branches on the ground in recognition of his status as the Messiah.

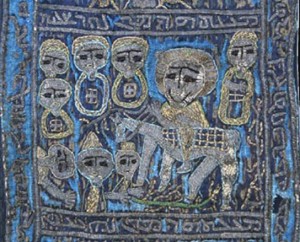

The earliest extant pictorial representations of the Entry into Jerusalem date to the fourth century, and the subject was popular across media throughout the Middle Ages. A highly compressed version of the episode appears on a fourteenth-century ivory diptych from the Abbey of Muri, Switzerland, which is decorated with Passion scenes. The right side of one of the leaves portrays a single disciple trailing the mounted Christ blessing two figures, who serve as shorthand for the multitudes. Equally schematic is the Entry into Jerusalem on the batrashil of bishop Athanasius Abraham Yaghmur of Nebek, produced in Syria in the fourteenth century. This long, embroidered stole shows three figures placing a palm branch before Christ, riding on an ass and attended by five disciples.

The lintel from the main portal of the twelfth-century church of San Leonardo al Frigido in Italy presents a more expansive version of the scene by illustrating all twelve disciples, their open mouths perhaps indicative of speech, and three small figures perched in a tree on the right-hand side of the composition. The last detail, common in depictions of the subject, relates to the prophecy of Zechariah, which describes children breaking branches from an olive tree and following the crowd into Jerusalem.

This year, the vernal equinox in the northern hemisphere falls on Sunday, March 20, marking the moment when the sun shines directly on the equator and the length of day and night are nearly equal. In anticipation of the change of season, The Index of Christian Art presents images thematically related to spring. First, a fifth-century mosaic from the synagogue in Zippori, an abandoned Roman-era town in central Galilee, depicts a personification of spring, identified by Greek and Hebrew inscriptions. Portrayed with roses in her hair, the bust-length figure is flanked by a blossoming branch and a bowl of flowers (on the left) and a basket of flowers and two lilies (on the right).

Second, a personification of March, labelled MARCIUS, graces a Catalonian textile from the late-eleventh or early-twelfth century. The figure appears to be chasing a stork (CICONIA), known as a harbinger of spring because of its migratory patterns. The figure holds a serpent, described in medieval bestiaries as an enemy of the stork, and a frog, perhaps a reference to the rainy season. Above is a personification of the north wind (FRIGUS), as well as a crescent moon and blazing sun. Last, a thirteenth-century Flemish Psalter depicts a figure pruning a stylized tree, an agricultural labor closely associated with the month of March.

Celebrated annually on February 14 as a day for courtship and romance, Valentine’s Day began as a liturgical celebration in honor of one or more Early Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The Roman Martyrology mentions two Valentines, both of whom were decapitated on the ancient Via Flaminia, the main artery connecting the city of Rome to the Adriatic Sea. One Valentine died in Rome and seems to have been a priest. The other, who may have been a bishop, was martyred approximately 60 miles away at Interamna (modern Terni).

The earliest extant connection between Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (1383): “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” February 14 was associated with courtly love as early as 1400, in a charter ostensibly issued by Charles VI of France (d. 1422). The text describes the festivities of the royal court, which included love poetry competitions, dancing, jousting, and a feast. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm evidence linking Valentine’s Day with the ancient Roman Lupercalia, a pastoral festival observed from February 13 through 15 to purify the city of Rome and to promote health and fertility.

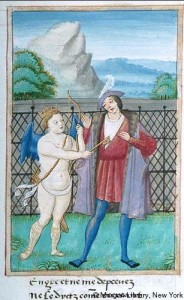

The Index of Christian Art is delighted to present four images thematically associated with Valentine’s Day. First, the nimbed Valentine of Rome is represented with the sword of his martyrdom in the fifteenth-century Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Morgan Library, M.917 and M.945). Second, a sixteenth-century Roman de la Rose contains a charming depiction of the God of Love locking the Lover’s heart with a giant key (Morgan Library, M.948). Third, a fourteenth-century ivory box cover of Parisian origin shows women defending the castle of love, a popular subject in late medieval courtly circles. The winged god of love at the top of the roundel prepares to launch his arrow, while women throw flowers at the attacking knights. Last, a sixteenth-century drawing from an Arma Christi and Prayers (Princeton University Library, Taylor 17), which portrays Christ’s heart with three blossoming flowers, is inscribed pyte, love, and charyte.