One of the little thrills those us who do academic research get to enjoy — whether we specialize in the arts and humanities or engineering and sciences — is when our favorite topics come up in films or on television. Imagine the excitement for anyone who studies Andalusian architecture when the quasi-medieval show “Game of Thrones” received rare permission to film inside the beautiful Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain.

Now perhaps it will come as no surprise that several of us here at the Index of Medieval Art are looking forward to the next series of “Doctor Who” — and the premiere of the first female Doctor (to be played by Jodie Whittaker)! — when the Doctor’s complicated history with historical accuracy resumes. For those of you regrettably unfamiliar with “Doctor Who,” it is a long-running BBC show about a long-lived, possibly immortal, time-traveling alien, and history nerds are among the most avid Whovians. To understand why, just watch the episode in which Pompeii was destroyed because aliens were building a spaceship in Vesuvius! In another episode, we learned that William Shakespeare’s plays include secret spells that open portals to other parts of the universe!

In the most recent series, the episode “The Eaters of Light” took place in Scotland in the second century AD. The Ninth Roman Legion, charged with the task of defeating the “barbarians” living in ancient Scotland, disappeared without a trace. When the Doctor and his companions investigate, things get a little strange. In the second century, the Roman Empire was trying desperately to maintain control of the lands of the “Picts” who lived north of what would very soon be the site of Hadrian’s Wall. The Picts are so called because these “painted people” (Picti) are mentioned in very early medieval texts. We know almost nothing about them, other than that they were fierce warriors, they painted their bodies before battle, and they left behind large stone monuments decorated with pictographic writing.

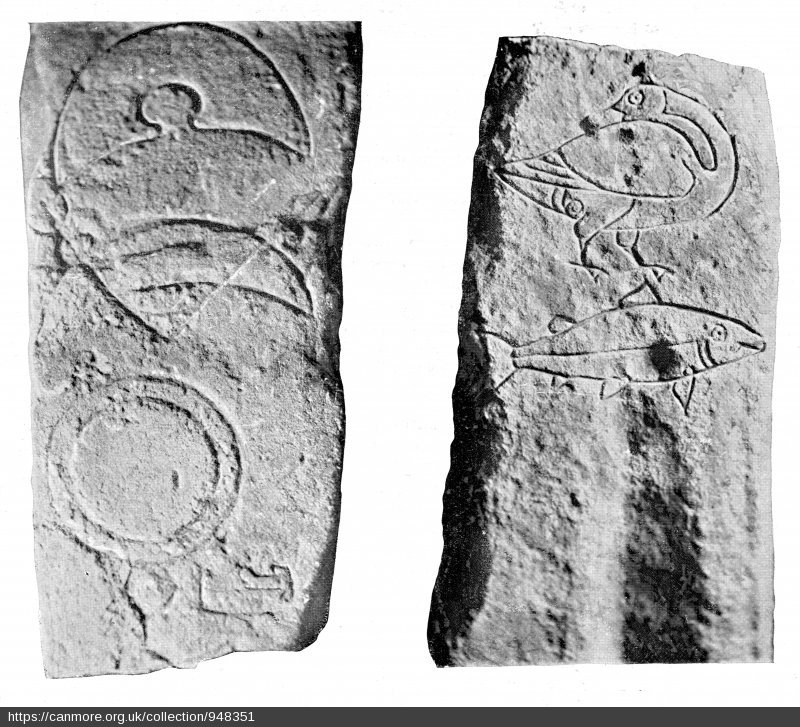

The Index of Medieval Art has almost 250 entries for “Pictish” artwork, most of which are large stones, either stelai or crosses. The stones usually appear in pairs, and the symbols carved on them depict inanimate objects like mirrors and combs, or crescents, and other geometrical shapes, as well as animals such as horses, dogs, birds and the enigmatic “Pictish beast.” It was this Pictish beast, a creature something like a hybrid of dolphin, horse, and dragon, or even (as some have argued), the Loch Ness Monster, that was the focus of “The Eaters of Light.” The episode proposed that it was a species of lizard-like alien monster that traveled through a great stone chamber-tomb in northern Scotland. Released in order to defeat the invading imperial army, it continued eating, threatening to consume all the light in our universe. Of course!

While this episode provides a fanciful interpretation of the Pictish stone carvings, it does actually highlight a point that art historians and archaeologists have been puzzling over for more than a century — just what do these symbols mean?

The stones were classified in the early twentieth century into three types, based upon their iconography and the level of detail in their carving. Class I stones, which date roughly to the fifth to seventh centuries, are relatively plain, and have only Pictish symbols inscribed upon them. Class II stones are slightly more ornate, with more effort obviously spent on not only carving the imagery but also on decorating the shape of the stone itself. They have not only Pictish symbols, but also Christian iconography such as very simple cruciform carvings. These are thought to date to the period of the seventh to ninth centuries, when conversion to Christianity was becoming more common in the region we now know as Scotland. Finally, Class III stones, which date to the later eighth and ninth centuries, are the most ornate. Their edges are highly decorated, the shape itself has been clearly hewn from the rock rather than simply incised upon it, and they have intricate carvings of knot-work and lace-work. Apparently used not only as upright markers or crosses but also as grave slabs, all of these Class III stones have explicitly Christian imagery, with many carved in the shape of crosses. None of them bear Pictish symbols, so these stones are interpreted as a last step in the Christianization of Scotland.

There are, however, two main difficulties in interpreting these Pictish symbol stones, though there are many theories as to what they represent. First, we are not entirely sure what they were for. Scholars have debated the issue for the last half century, arguing that they were monuments marking important meeting places or boundaries, or that they were memorials to particular individuals, families, events, or even that they might have been political statements opposing the spread of Christianity in early medieval Britain. Inscriptions are not helpful for interpretation either. While ogham writing in Ireland and Wales is found on stones that include Latin inscriptions, so that each stone is like a Rosetta Stone (with the Latin inscription in each case serving as a key to interpreting the ogham text), we do not currently have such a direct method of interpreting Pictish ideograms.

The second problem is the dating. Surviving Pictish stones suggest a development from the simple, presumably pagan, Pictish animals and shapes of Class I stones to the elaborate crosses in Class III. Like much archaeological evidence from the post-Roman fifth and early-sixth centuries in Britain, this dating is often based upon our expectations affected by early medieval texts like Bede’s Ecclesiastical History or Gildas’s On the Ruin of Britain, none of which were written in Britain in the period they describe. Unlike human or plant remains, stones cannot be radiocarbon dated. Even if we wanted to make the attempt at dating, for example, organic elements of the soil beneath the stones, only a few of the stones are actually still in situ. So the dating of the Pictish stones depends on parallels in manuscripts such as the Book of Durrow, and upon what we currently think about the history of the arrival of Christianity in Scotland. Even if we were able to determine with absolute certainty when exactly these stones were first inscribed and placed in the landscape, that account would still not consider the many succeeding generations and their many possible uses for these stones.

The Pictish stones in the Index of Medieval Art, especially the Class I stones, are part of a wider discussion of very early medieval society in Scotland. The Picts are the people that sixth-century and later texts blame for the beginning of the end of Roman Britain. Their raids along coasts to the south created defensive problems at a time when the Roman military presence in Britain was declining. Over the last fifty years or so, archaeological excavations of cemeteries in Scotland have increased our understanding of the monumental commemorations of death among the people who raised these decorated stones and crosses. The iconography on the stones that these people left behind is one of the few sources that modern scholars can work with to learn about the Picts and their world — and it also turns out to be a great source of inspiration for science fiction television.

This guest blog post was written by Janet Kay, a CLSA-Cotsen postdoctoral fellow at the Princeton Society of Fellows. She studies the history of fifth-century Britain, looking at burial practices to study a period for which there are no surviving texts. Janet uses material culture and funerary rites as primary sources to explore how fifth-century communities understood themselves and their newly-arrived neighbors from the continent and how invested they were in maintaining connections with their Roman past.

The Index invites paper proposals for two sessions at the 2018 Medieval Congress in Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, on the theme of “Iconography and Its Discontents.”

Modern scholars often express discomfort with the term “iconography,” caricaturing its study as obsessed with rigidified taxonomies, elaborate stemmae, and the abstract pursuit of textual analogues for free-floating images. Yet the fundamental questions that drive iconographic studies remain central to scholarship in art history and many other medievalist disciplines. What did a medieval image mean, and to whom? How did these meanings change in different contexts and in the eyes of different viewers, and what can this tell us about the values and practices of the society in which they were made and viewed? The ways in which researchers answer these questions, meanwhile, has changed dramatically, bolstered by new methodologies and the increasing availability of digital tools to quantify, compare, and analyze a wide range of medieval images. Such advances suggest that the study of iconography not only is “not dead yet,” but is very much alive and open to reassessment.

Our two sessions capitalize on the new vitality of current iconographic studies by gathering papers that reexamine the potential of iconographic work for medievalists, prioritizing work that pushes past traditional approaches to engage with the new questions, new methods, new disciplines, and new technologies of greatest impact within the field. Following on the centennial and digital relaunch of Princeton’s recently renamed Index of Medieval Art, one of the first and longest-lived iconographic repositories of its kind, the session aims to chart a new path in a scholarship transformed by both technological advancements and disciplinary creativity.

Session I: Iconography and/as Methodology. What questions do today’s scholars ask of medieval images, and what approaches do they take to answering them? Do their efforts represent a break with the past or a continuation of it? What disciplines do they most engage? For this panel, we invite papers that explore the impact of new methods, whether from art history or from other disciplines, on modern understanding of how medieval images did their work for their makers and viewers. Papers that assess the relevance or revision of past approaches are also welcome.

Session II: Iconography and Technology. How have digital resources transformed the ways in which scholars approach the study of medieval images and their meaning? What new questions (and answers) are now possible, and what remains the same? For this panel, we seek papers that evaluate the impact of online collections, databases, and other digital tools on image-based scholarship in any discipline. Both case studies and broader analyses are invited.

Proposals are invited from scholars at all levels and in any relevant discipline. To submit, please send a Participant Information Form (https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/submissions) and one-page abstract to:

Pamela A. Patton, Director

Index of Medieval Art

A7 McCormick Hall

Princeton University

Princeton, NJ 08544-1018