The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to launch a new series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank our interviewees for their time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I’m not a medievalist but my work in Renaissance iconography has always depended on research material from earlier times. I had my first course in art history as a senior in high school, Mary Institute, St. Louis, 1942–1943. I majored art history at Washington University, St. Louis, receiving my M.A. (1949) under H.W. Janson, and did graduate work at the Institute of Fine Art, NYU, with Erwin Panofsky and others. I received my PhD on the basis of three related published articles in 1973.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located then? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

My first visit to the Index was in 1950. For a seminar with Panofsky, I was investigating the sudden appearance of the Infant St. John the Baptist in the Florentine early fifteenth century. The Index was in McCormick Hall. I met Rosalie B. Green and worked with her and Isa Ragusa. I also, by chance, met Professor Morey on that visit. I quickly found that the arrangement of the Index card catalog did not offer simple searching under the Baptist’s name. Learning the biblical structure of the index then helped me broaden the conceptual basis of my project and enriched my results.

In my years of working in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, it was always reassuring to know that the copy of the Index was there for consultation. In the 1980s, when I was a member of the Getty AHIP team, the precedence of the Index was a motivating factor in creating new computer tools for art historical research.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I am told that my article on the iconography of the Infant St. John, published in 1955 in The Art Bulletin remains useful up to the present day.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database? Where do you think Index work should go next?

With the appointment of Pamela Patton, the Index has finally hit its stride. Along with its change of name, broadened constituency, and superb technical improvements, the Index is fast becoming a major research center. It seems to me obvious that these advances indicate that the direction The Index of Medieval Art is going is the right one.

This blog post is the ninth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce our student worker Brooke Jurgenson.

What year are you in your Princeton education? What are some of your favorite courses or subjects?

I am a second-year student in the Class of 2026. I intend to declare psychology as my major, but I also love philosophy, literature, and art history. My first year, I really enjoyed the Western Humanities Sequence, which traced the development of the Western intellectual tradition through such foundational works as Augustine’s Confessions and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This semester, I am bridging my interests in psychology and philosophy with the course “The Psychological Foundations of the Mind” and branching out into linguistics by taking “On the Origins and Nature of the English Language.”

What do you do at the Index?

At the Index, I go through different iconographic categories, such as Virgin Mary, Dormition and Christ, Presentation, and add subjects to make the categories more comprehensive and accessible for researchers. For instance, I might add the subject tags “Joseph the Carpenter,” “Anna the Prophetess,” and “Dove” to all the records containing this imagery in scenes of the Presentation of Christ. I also collaborate with the Index research staff on refining the subject taxonomy and applying it more widely to records.

Aside from your experience at the Index, what was the most interesting job or internship you had?

In addition to fostering a love of medieval art at the Index, I have learned much about Princeton’s modern sculpture collection by serving as a Student Art Tour Guide with the Princeton University Art Museum. I lead small group tours around Princeton’s campus, highlighting the subtleties of Henry Moore’s bronze craftsmanship and Jacques Lipchitz’s mysterious abstractions.

What have you learned about medieval art since working for the Index? Has anything surprised you, or does anything stand out as extraordinary or curious about medieval art?

I absolutely love medieval art! Beautiful florals, ornate Latin scripts, gold pigments, and captivating renditions of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child regularly grace my screen. My appreciation for medieval art has grown immensely, and I have come to recognize just how rich and varied the subject area is.

I also never fail to come across the most mysterious and fun “hybrid creatures.” It is only here that I stumble across cats playing hurdy-gurdies and half-dragons slaying monsters. Medieval art truly expands your imagination.

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

This past summer, I took a somewhat impromptu trip to Berlin and visited the Bode Museum. I reveled in the amazing Byzantine collection there. Aside from medieval art, I enjoy Impressionism because of how it captures the ephemeral. My favorite work (as of right now) is Claude Monet’s “View of Vétheuil” painted in 1880, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Accession number 56.135.1).

What’s your favorite building or spot to sit on campus?

When it is warm outside, I love sitting on a bench in the garden behind Maclean House while reading. It is the perfect place to listen to the birds sing and feel the serenity of nature. I also love gazing at the stained glass windows of the Princeton University Chapel, watching the colorful dances of light play out in the sacred space.

Coffee or tea?

I avidly drink both coffee and tea, but I am a tea lover by heart. A steaming cup of freshly brewed green tea is all I need to be content.

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2024.

Although some scholars have claimed to see something like pizza in a wall painting at Pompeii, most historians trace the origins of modern pizza to sixteenth-century Naples. However, researchers at the Index of Medieval Art have discovered previously unrecognized medieval evidence of pizzerias in manuscripts dating at least two centuries earlier.

These early pizza-making scenes depict workers baking crusts, as in the miniature of a fifteenth century Book of Hours (Princeton University Library, MS Garrett 54). Notice how the pizza chef thrusts a long-handled peel with a round crust into a roofed pizza oven. Other steps in the preparation of crust have been identified in the iconography of pizzerias, including a hybrid figure tossing a circle of dough into the air to give the pizza its custom shape. Tossing dough in the air has long been the preferred method in pizza preparation to thin out the crust and give it its signature stretchy, glutinous finish.

Our research found that the toppings for pizza throughout the medieval period would have run the gamut. The typical meats and vegetables that popularly eaten today would have featured on pizza in the Middle Ages, too…with one major exception: the edible berry of the plant Solanum lycopersicum, more correctly identified as the Amoris pomum and commonly called the “the tomato.” Tomato sauce on pizza was strictly prohibited due to the prevalence of the belief that the love apple is the devil’s fruit. But pizza was always a highly customizable dish, and pizza mongers were apt to use any combination of sauces with any number of toppings to suit their palates. Pineapple and anchovies on pesto with casu martzu was a particular favorite among both penitents and unrepentant heretics alike.

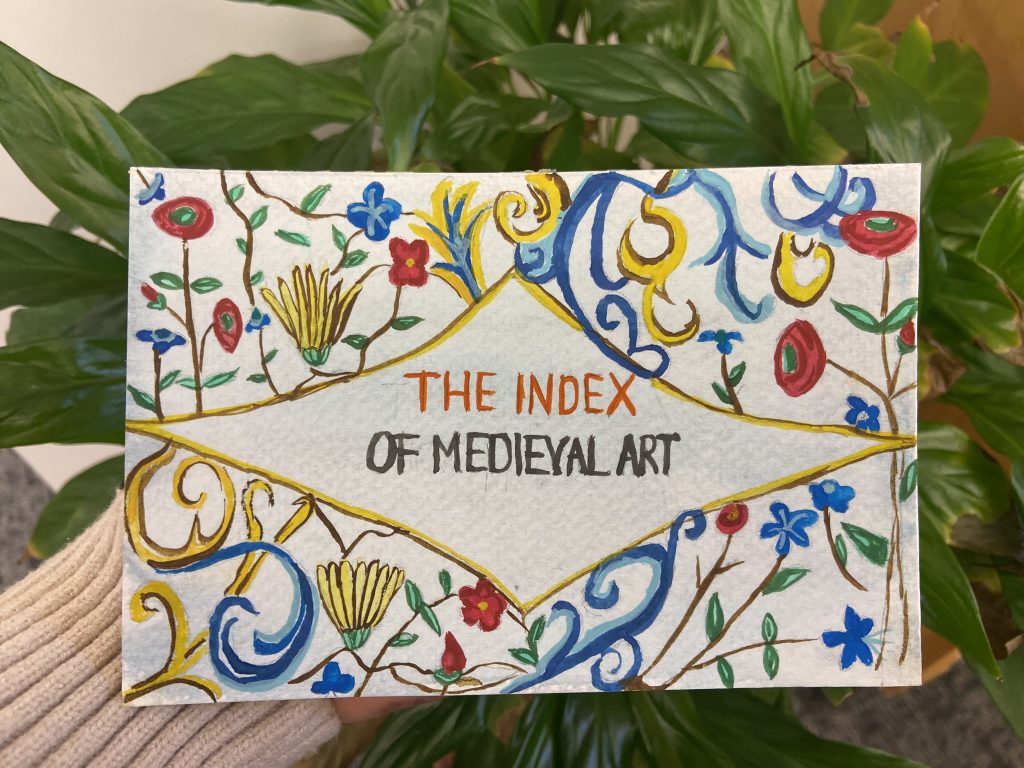

You can imagine our surprise at finding in one late fifteenth-century Neapolitan cookbook, known as the “Cuoco Napoletano,” a recipe for a type of blood sausage known as cervellato (manuscript inscribed “Cirvelato de carne de porco ho di vitelli”) with a mention of its use in pizza preparation. Legendarily, and much like today, sausage was a favorite topping among medieval consumers of pizza, and the following leaf in the cookbook describes such usage in great detail. Or are you a fan of fungi on your pies? Mushrooms too made it onto the menus of pizza chefs, and some illustrations in medieval manuscripts show the fleshy morsels lined up and ready to chop.

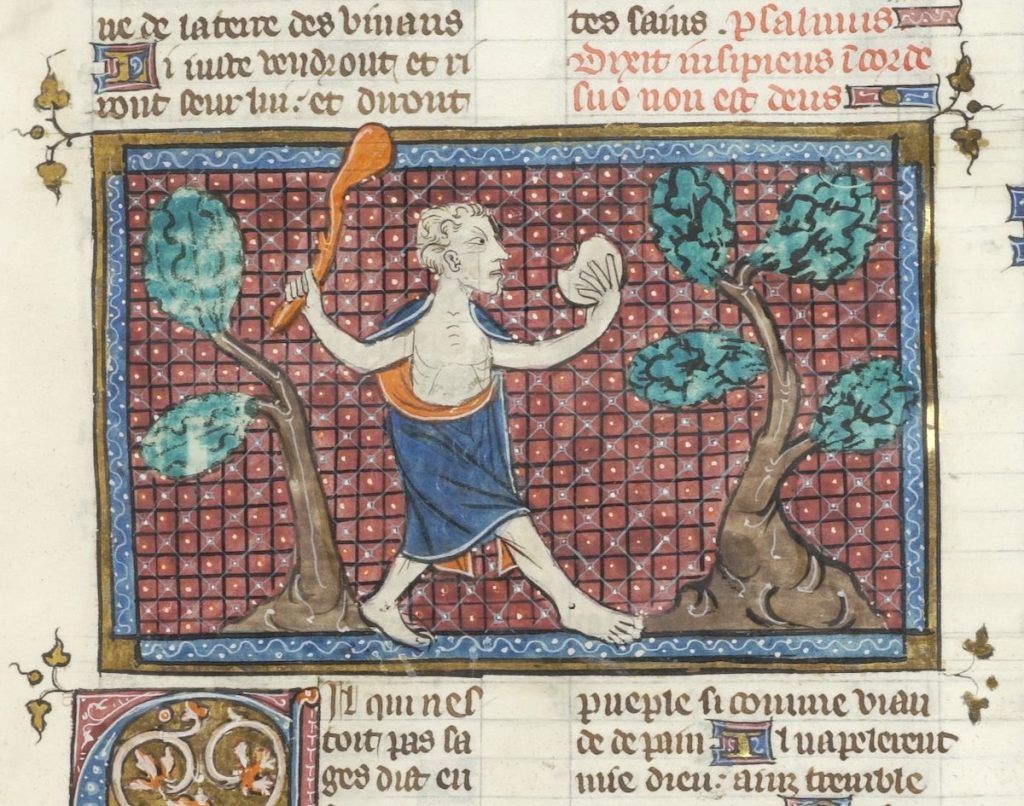

Whether deep-dish or thin with extra cheese, pizza was prized in the Middle Ages. Pizza to go wasn’t out of the ordinary, either, but the pie would have to be fiercely guarded by its consumer. Eating a slice, or “wolfing ’za” as the medieval collegiate vernacular would have it, was often a perilous, two-handed operation. In one medieval image, you’ll notice that a large man chowing down on a delicious slice folded in one hand was required to wield a club with his free hand to ward off would-be pizza poachers!

It was also a seasonal favorite. Such early forms of a pizza would have been regarded as the perfect addition to any menu on the first day of April.

(And by the way, April Fool!)

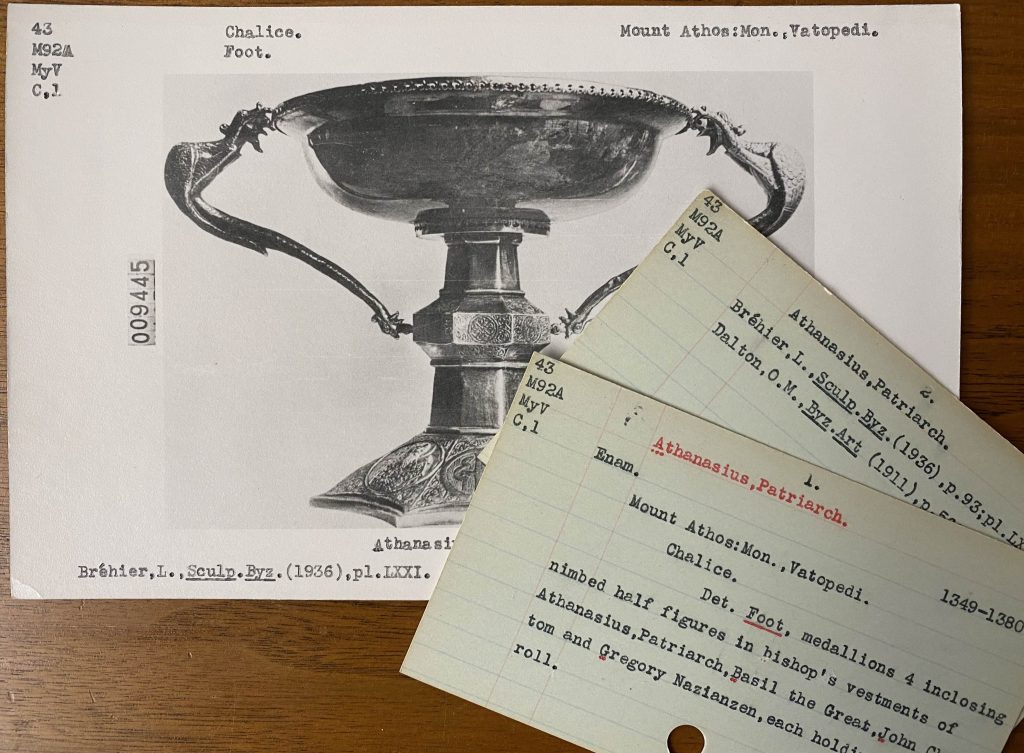

We are very pleased to announce that Kyriaki Giannouli has joined the Index remotely for a three-month, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works on Mount Athos (Greece) into the database!

Kyriaki is a doctoral candidate specializing in Byzantine History at the University of Ioannina and a professional conservator of paintings. Her research focuses on examining the significance of Greek landscapes within the travelogues of Western Holy Land pilgrims from the 12th to the 17th centuries. She is an expert in Byzantine portable icons, frescoes, coins and seals and has hands-on experience in creating specialized conservation reports and working with databases.

At the Index, Kyriaki has started working on enamel and metalwork backfiles and has already made digitally available several objects on Mount Athos, including a fourteenth-century chalice from Vatopedi monastery (Index system number mar20240205001) and an eleventh-century book cover from Lavra monastery (Index system number mar20240212001). Her position requires her to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. This will allow scholars worldwide, who are not able to travel to use the print Index on the Princeton campus, to access these images and their metadata. We are very excited and grateful to have Kyriaki join us in this collaboration!

This position is part of a multi-year project focusing on Mount Athos-related collections at Princeton (https://athoslegacy.project.princeton.edu/) and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.

This blog post is the eighth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce our student worker Tinney Mak.

What year are you in your Princeton education? What are some of your favorite courses or subjects?

I’m a junior right now studying computer science. Some of my favorite classes that I’ve taken are “Everyday Writing in Medieval Egypt” and one where I learned how to read hieroglyphics (fulfilled my childhood dream).

What do you do at the Index?

I mostly deal with tagging subjects on works of art to make sure that people doing research have an easier time finding the materials they want.

Aside from your experience at the Index, what was the most interesting job or internship you have had?

The most interesting internship I’ve had was last summer where I spent eight weeks in Malaysia analyzing a diabetes dataset. I learned a lot from the people I worked with and also really enjoyed exploring the country.

What have you learned about medieval art since working for the Index? Has anything surprised you or does anything stand out as extraordinary or curious about medieval art?

Since working for the Index, I’ve been continually impressed by the amount of skill and knowledge it must take to decipher what’s going on in a piece of art, especially since objects often get extremely worn down through time. It’s always interesting learning about the vast number of different work of art types that I didn’t even know existed (current favorite: croziers!).

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

My favorite place that I’ve visited is probably Budapest. I remember taking the ferry down the Danube and being in awe of the Liberty Monument on the hill.

What’s your favorite building or spot to sit on campus?

The Mathey common room because of the comfy couches, high ceilings, and occasional piano playing.

Coffee or tea?

Tea! Specifically, a nice cup of Earl Grey.

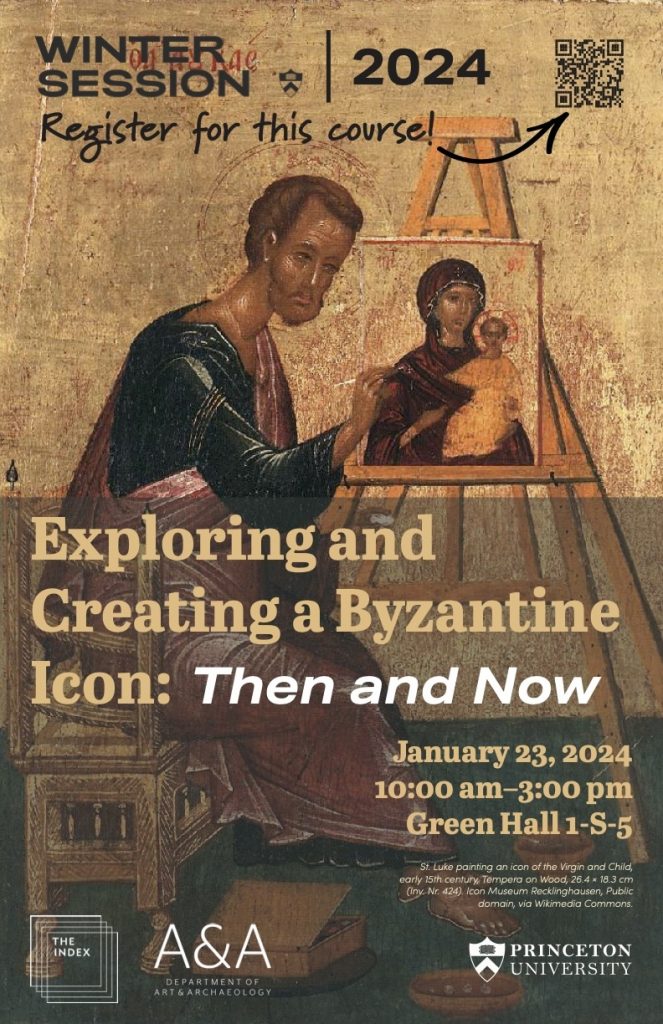

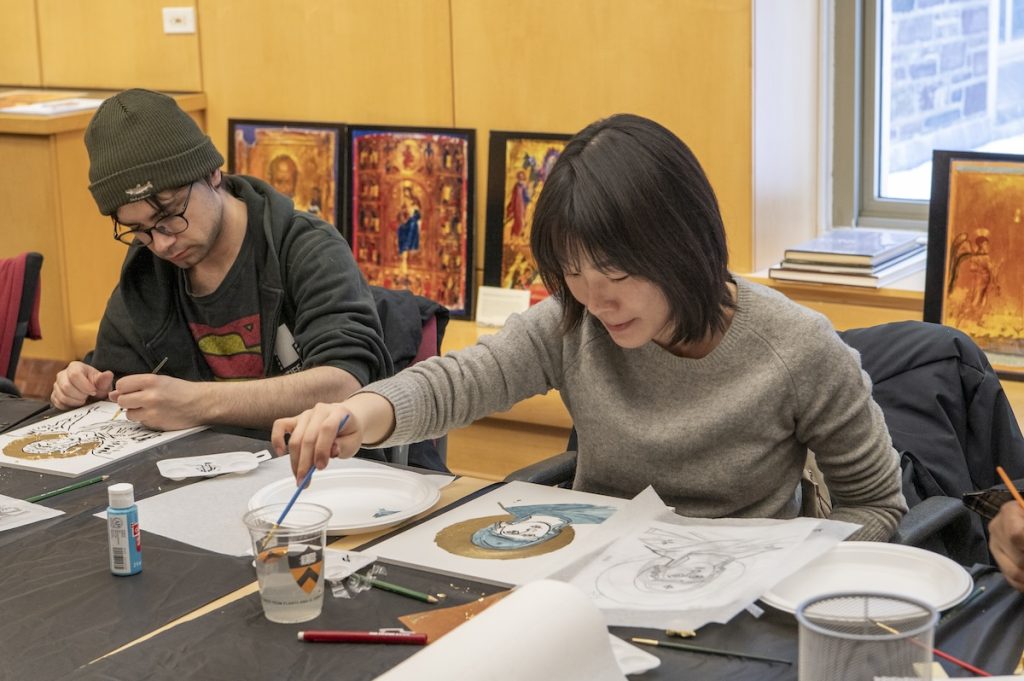

The Index of Medieval Art was delighted to offer its second Wintersession, “Exploring and Creating a Byzantine Icon: Then and Now,” on January 23rd, 2024. Its fifteen participants included Princeton staff, faculty, undergraduate and graduate students. In the first part of the workshop, they learned about the history and creation of Byzantine icons. In the second, they had the opportunity to create their own icons using modern artistic materials.

Index Art History Specialists Maria Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage led the workshop, opening with a presentation on the Index resources and delving into some questions about iconography using large reproductions of the icons from Mount Sinai, generously loaned by Visual Resources, as a basis. The group discussed the iconographic details in works of art, exploring the subject matter in icons that generate tags in the Index database. Jessica invited the students to observe the figures and scene in a twelfth-century Sinai icon of the Annunciation (Index system no. 57527), looking for major and minor details in the painting, as small as an octopus swimming underwater. Alessia introduced participants to the way Byzantine icons were displayed and their devotional practices by examining a folio from the Hamilton Greek Psalter (Index system no. 103381).

The first guest lecturer, local icon painter Maureen McCormick, showed the participants how to make the binder for egg tempera paint by mixing egg yolk and … No, not water … rather, white wine! Maureen showed the class all the tricks of the icon painter, including where to buy authentic pigments, how to grind them, and how to literally use one’s breath to “blow” gold leaf onto a red clay bole sample, which formed the nimbus of a saint. A short Instagram reel was made by Kirstin Ohrt, Communications Specialist in the Department of Art & Archaeology, to show Maureen’s breathtaking lesson in action, and you can check it out here: https://www.instagram.com/artandarchaeologyprinceton/reel/C2ud3gZLAJW/.

The afternoon session was led by Department of Art & Archaeology graduate student and icon painter, Megan Coates, who spoke about her own work with icons, as well as their importance for memory and communication. As part of an organized hands-on activity, participants created their own Byzantine icons using templates designed by Megan or choosing their own models from books or memory. Acrylic paint, brushes, drawing materials, gessoed panels, as well as gold and silver leaf materials were supplied by the Princeton Office of Campus Engagement. The outcomes were astonishing!

It was a pleasure to observe the participant’s ideas and skillful process unfold as they engaged in the long-treasured art of icon-making. One participant Sigrid Adriaenssens, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, wrote to us after Wintersession and said, “Thank you so much for organizing this workshop. It opened a whole new world to me that I didn’t know existed at Princeton. I really enjoyed learning about the Index, icons, and how they are made. The speakers Maureen and Megan were also very interesting and exciting to listen to!” Another participant, Zi (Zoe) Wang, visiting doctoral candidate and researcher at Princeton from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, said she felt transported by the instrumental music we played during the hands-on activity. Zoe said about the experience, it was like “immersing myself in meditation.” We couldn’t agree more!

Are you interested in learning more and researching icons at the Index? Here are some general tips for starting an Index search about Byzantine icons, especially if you do not know exactly which icon you are looking for!

However, these results might be too broad, so if you want to refine them you can keyword search the word “Byzantine” on the upper right search window of the database, and then filter by these other controlled terms we just mentioned, such as Work of Art Type “panel” or Medium “wood.” But if you want even narrower results, or if you know the iconography you are interested in, such as the iconography of an angel, or searching for angels by name, as in the case with the Annunciation image, you can filter by the Subject “Gabriel the Archangel.”

If you have any questions about starting research with the Index resources, fill out our inquiry form and we will be in touch: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/.

Finally, this Wintersession workshop could not have been possible without the generous support of the Princeton Office of Campus Engagement, the Department of Art & Archaeology, and the Index of Medieval Art. Thank you to all who helped plan and participated in this event!

As editorial staff at the Index continue cataloging our physical backfiles, which contain over 200,000 photographs of works of art in sixteen media categories, we are happy to announce that at last, all our print records of gold glass objects have been fully digitized in the Index database! In gold glass, an image in gold leaf is fused between layers of glass. Gold glass was a favored art form in Hellenistic Greece and during the Roman period, often decorating the bases of feasting vessels, such as bowls, cups, and plates, with hidden pictures that would slowly be revealed during the consumption of food and wine. The newly digitized “Gold Glass” backfiles document over 650 objects from about 60 locations. Most examples are identified as vessels, medallions, or plaques (Fig. 1).

The glittering portraits on these glass objects, now mostly fragmentary, are usually bust length and often show whole families. These are classified under the Index subject “Family Group,” while the subject “Married Pair” is used for images depicting a bride and groom, sometimes crowned by Christ. Gold glass objects are frequently associated with marriage celebrations, and several pieces retain the names of the men and women depicted with inscriptions of good wishes. Frequently, this inscription is the Latin drinking toast “PIE ZESES” (“Drink to live,”), either in full or abbreviated, although a fourth-century gold glass fragment from Rome, now in the British Museum, bears the more sentimental words “DVLCIS ANIMA VIVAS” (“Sweet soul, may you live [long]”) around the heads of the newlyweds (Fig. 2).

Several gold glass objects contain other paired figures, especially Peter and Paul the Apostles, as the patron saints of Rome, and Adam and Eve, commonly represented in the Fall of Man scene. Old Testament narratives and figures, such as Moses, Abraham, Daniel, and Jonah were popular, and Christian miracles were also frequently depicted on vessels. The Index database contains just over fifty miracle scenes executed in the gold glass medium, including the Raising of Lazarus, the Miracle of Loaves, and the Wedding at Cana, suggesting that healing themes held some favor among patrons. The objects may also have served a commemorative function.

Some surviving gold glass objects contain Jewish iconographic motifs, including the Temple implements, such as the menorah, shofar, etrog, and Torah Ark. These implements can be found in the Index database by browsing the Subject list, or by searching for “gold glass” as a term and filtering by the Style/Culture “Jewish.” Mythological figures and narratives from the classical world were also favored subjects to depict on gold glass vessels. The Herculean labors, sea-nymphs, and cupids can be identified on some fragments. Other well-represented motifs in the medium include the “Good Shepherd,” which has iconographic connections to the ancient Greek ram-bearing cult figure Kriophoros. There remains much to discover and assess about images in gold glass and their meanings, production, and patronage throughout the late antique, Roman, and Byzantine periods, making the Index an essential study tool. Now, with increased access, more researchers can learn how this rather fragile art form documents fashion, commerce, rituals, and historical names and epigraphs from ancient daily life (Fig. 3).

The Index gold glass backfiles received significant attention by Ryan Gerber, our 2019 summer intern from the Rutgers School of Communication, who is now a Marquand Art Library Collections Specialist. Gerber inventoried the collection and wrote about his impressions in a blog post called “A Face in Gold Glass.” After Henry D. Schilb, Index Art History Specialist in Byzantine Art, finished adding the collection with the help of Gerber’s inventory, he noted that many gold glass objects recorded in major nineteenth century catalogs did not survive into the modern era. Thus, the publications that earlier Index catalogers used in their research may have contained the last known record of an object’s existence. Schilb said, “it was surprising to learn that many of the gold glass objects entered into the Index files have been lost to time, and at least one of them was apparently reduced to dust in the collection where it was last recorded. Not surprisingly, we have also simply lost track of several examples that were originally cataloged by Indexers before the Second World War.” With too little information to go on, the Index cataloger can sometimes upload only a drawing from the catalog and record only a “Last Known Location” for objects presumed lost to history. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this in the database by giving “Unknown” as the current location with a “Last Known Location” to identify the place where an item was last known to exist. This can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are either simply lost or are now in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s true current location, that bit of data can sometimes elude us, so we always welcome intelligence from anyone who might have a good lead!

It is a great achievement when we can complete an entire category in the backfiles with newly researched information, including updated location names, fuller iconographic descriptions, and new or updated terms from Index vocabularies to expand the findability of work of art records. We ought to be clear, however, that we do not claim to have recorded every known example of any medium or type of object. That must remain an ongoing project. Nevertheless, the whole Index team is thrilled to make the gold glass corpus of the original Index card catalog fully available in the database. If you want to see for yourself, you can browse “gold glass” records by Medium more fully here: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/list/ListMediums.action. You can also reach out to us with any inquiry here: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/. Please let us know how the Index can improve the records we have, or find out how the Index can serve your own research needs.

Cheers!

Further Resources

Garrucci, Raffaele. Vetri ornati di figure in oro: Trovati nei cimiteri dei cristiani primitivi di roma. Rome: Tipografia Salviucci, 1858.

Deville, Achille. Histoire de l’art de la verrerie dans l’antiquité. Paris: Morel, 1871.

Vopel, Hermann. Die Altchristlichen Goldgläser: Ein Beitrag zur altchristlichen Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte. Freiburg im Breisgau: J. C. B. Mohr, 1899.

Morey, Charles Rufus. The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library: With Additional Catalogues of Other Gold-Glass Collections, ed. Guy Ferrari. Vatican City: Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1959.

Meek, Andrew. New Light on Old Glass: Recent Research on Byzantine Mosaics and Glass. London: British Museum Press, 2013.

Howells, Daniel Thomas. A Catalogue of the Late Antique Gold Glass in the British Museum. London, British Museum Press, 2015.

For the second year, the Index of Medieval Art was pleased to offer the Graduate Student Travel Grant in an effort to support a non-Princeton student who wishes to attend the Index conference in person. The recipient this year was Anahit Galstyan, a PhD student in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who joined us in Princeton on November 11 and attended the “Whose East?” conference. We are glad to share her thoughts.

“It was an immensely enriching experience, and I found great enjoyment in the proceedings. The presentations were not only intellectually stimulating but also delivered with an engaging flair that made the entire event thoroughly enjoyable. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks for the generous grant that made my participation in this conference possible. Without such support, this experience would have remained beyond my reach. I think that by facilitating students’ attendance through the Graduate Student Travel Grant, the Index of Medieval Art contributes to the broader dissemination of knowledge and the fostering of academic dialogue.

“I found great merit in the engagement of the meticulously curated selection of participants in exploration and reevaluation of the entrenched dichotomies between East and West, Islam and Christianity. The discussions surrounding cultural interactions within the expansive region of the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond also further contributed to the recent scholarly discourse on questioning the traditional disciplinary predisposition of Byzantine studies to prioritize its metropolitan center, this way contributing to the reshaping of the dominant narratives in our field.

“Given my focus on the culturally and socially diverse medieval city of Ahlat and its funerary architecture, the exploration of intercultural exchanges at the event deeply resonated with my own work, making it not just intellectually engaging but also personally significant. I enjoyed all the presentations, with one of the standouts being Christian Raffensperger’s talk on the classification and categorization of Rus in medieval times. His insights provided a refreshing perspective that challenges established norms in the field. Anthi Andronikou’s presentation on interfaith dynamics between Eastern Christian and Islamicate art was also especially captivating among the various talks.

“I want to particularly highlight Gohar Grigoryan’s presentation, which provided a fascinating glimpse into first-hand accounts, shedding light on the intricate dynamics of Armenian elite self-fashioning in the thirteenth-century geopolitical context. It was particularly noteworthy in challenging the traditional view of a relatively uniform Armenian society during that era. Her paper was not just intellectually engaging but also skillfully presented, prompting me to reflect on my own research on identity creation. Grigoryan’s work emphasized the importance of examining the individuals I study not only in relation to external political dynamics but also in relation to each other, encouraging a more nuanced exploration of subtle expressions of personal identity. Additionally, Erik Thunø’s exploration of South Caucasian cross steles added another dimension to my understanding, urging me to consider similar cultural expressions beyond simple transmission.

“While attending the conference was truly delightful, I was also thrilled to have the opportunity to visit the numismatics collection. Handling and closely examining Byzantine, Cilician Armenian, and Seljuk coins was a highlight for me – an opportunity that I doubt I would have had as a grad student otherwise. Additionally, spending time in the Index was a wonderful experience. Dr. Maria Alessia Rossi and Dr. Henry D. Schilb provided invaluable assistance in navigating both physical and online catalogs to trace some types of funerary objects I study, such as censers and lamps, that are scattered across different collections worldwide. Finally, I am immensely grateful to Professor Pamela Patton for her generous hospitality and to Fiona Barrett for ensuring that I was well-fed throughout my stay.”

And we thank YOU, Anahit, for your thoughtful comments and for sharing your experience with the Index readers!

Anahit Galstyan is a PhD student in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on Christian-Islamic interactions in medieval Anatolia as manifested in the transculturation and the transmission of architectural knowledge.

We are excited to announce a short-term graduate opportunity at the Index of Medieval Art! This is a two to three-month remote, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works of art on Mount Athos into the Index database. The position would require the student to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. They will be trained in Index norms in cataloging works of art, describing the iconography, transcribing inscriptions, and adding bibliographic citations.

The position is part of a new multi-year project, Connecting Histories: The Princeton and Mount Athos Legacy, that aims to create an international team of faculty, staff, and students that will explore and bring awareness to the rich, complex, and remarkable historical and cultural heritage of Mount Athos, and its connection to Princeton. This opportunity offers a stipend of $2,500 and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.

The deadline for applications is December 1, 2023. For more details about eligibility criteria and the application process, please visit the “Announcements” page on the Connecting Histories website.

Index staff have been busy at the Index working on a variety of projects and launching free public access to the database, which officially opened on July 1, 2023. It has been wonderful to see a warm reception from researchers, and recent user statistics show that the Index database is reaching hundreds of unique users per day.

We will continue offering Zoom tutorials and the next one is planned for the Spring 2024 semester. If you have been wondering how to get the best results out of your searches and see more about what the Index covers, please stay tuned for the next date, or write to us directly with your research inquiry!