On May 19-20, 2017, international and US Scholars will gather at Princeton to examine the near-intact monastic treasury of San Isidoro in Leon, in northern Spain, as a springing point for larger questions about sumptuary collections and their patrons across Europe and the Mediterranean across the Middle Ages. Topics of inquiry include Islamic law and sumptuary production, Christian manuscripts and metalwork, patronage and royal studies, identity and gender studies, and cultural and political history. The diversity of questions and perspectives addressed by the speakers will shed light on the nature of Leon as a paradigmatic treasury collection, as well as on the broad efficacy of multidisciplinary study for the Middle Ages.

Follow the link below for a full schedule and (free) registration information. We hope to see you there!

In medieval terms, March 25 was about as symbolically busy as a day could get. Already noted in the Julian calendar as the date of the vernal equinox, it is identified in the Golden Legend of the chronicler and archbishop Jacopo da Voragine as the date of an unusual number of auspicious Biblical events: Adam’s and Eve’s fall into sin; Cain’s murder of Abel; Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac; Melchisidek’s offering of bread and wine to Abraham; the martyrdom of John the Baptist; the deliverance of Saint Peter; the martyrdom of Saint James the Great; and the Crucifixion. Still more strongly associated with this date was the Annunciation, at which, according to Luke 1:26-28, the archangel Gabriel brought word to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive the son of God: “And in the sixth month, the angel Gabriel was sent from God into a city of Galilee, called Nazareth, to a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. And the angel being come in, said unto her: Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women.”

Gabriel’s announcement to Mary inaugurated the Christological narrative that governed all the feasts of the liturgical year, so it is unsurprising that this event should be highlighted in medieval calendars, where its proximity to the start of spring also led many to treat March 25 as the beginning of the new year.

The Annunciation is among the most consistently depicted subjects in medieval iconography; it is found in everything from early Christian catacombs and sculpted facades to books of hours, mosaics, and panel paintings. Its composition and details vary in accordance with its setting: the Virgin might appear on a throne, in a loggia, in a bedroom, or outdoors, and she often is shown spinning or reading. A variant of particular interest is the depiction of the Annunciation at the Spring (as it is catalogued in the Index), also known as the Annunciation at the Well. Inspired by accounts preserved in early apocryphal texts such as the Protoevangelium of James and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, this variant depicts the Virgin greeted by Gabriel as she is fetching water, the first of two successive meetings in which the angel delivers his news.

The Annunciation at the Spring emerged in late Antiquity and flourished in Byzantium and the visual traditions close to it. An early exemplar appears on a fifth-century plaque, possibly a book cover, now in Milan Cathedral Treasury. Here, a small square scene of the Annunciation initiates the narrative of Christ’s life; it depicts the Virgin Mary kneeling by a stream, pitcher in hand, as she looks back to receive the angel’s greeting. In a much later manuscript example, a twelfth-century Homilies of James Kokkinobaphos (Paris, BnF, MS gr. 1208, fol. 159v), two meetings are implied: at left, Mary dips her pitcher into a well as she turns to hear Gabriel’s message; at right, she approaches a house where she will receive the angel a second time.

A more dynamic version of the well scene appears in an early fourteenth-century mosaic in the Church of the Savior at Chora in Istanbul: composed on a pendentive below one of the structure’s domes, it positions the angel as a fluttering visitor who descends the curved surface to greet Mary as she teeters over the well below.

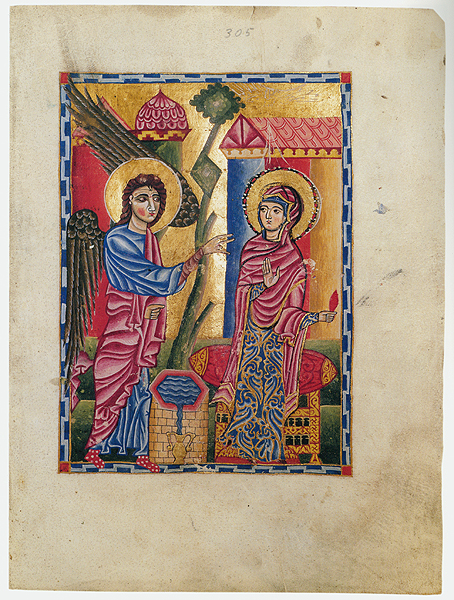

Other cultures with close ties to Byzantine traditions also adopted the Annunciation at the Spring. The scene appears among twelfth-century mosaics of the Life of the Virgin in the transept of the church of San Marco in Venice, as well as in the early fourteenth-century Armenian manuscript known as the Glazdor Gospels (Los Angeles, University of California Research Library, MS. 1, p. 305).

In the Gospels manuscript, a flattened, stylized well and pitcher offer only a vestige of the original iconography as they stand between Gabriel and the Virgin. The figures’ static postures, animated only by Gabriel’s speaking gesture and the Virgin’s raised palm, recall western Annunciation scenes, but Mary’s gilded brocade and the ogival dome at the top of the composition attest to its eastern roots.

The medieval church season of Lent officially opened with Ash Wednesday, the Wednesday after Quinquagesima Sunday (the period of fifty days before Easter). The observance of Ash Wednesday marked forty fast days before Easter, not counting Sundays. During Lent, medieval Christians were forbidden to consume meat, eggs, dairy and animal fats, except on the permitted Sundays which were viewed as a “mini-Easter.” By adding a level of restraint to their daily lives, medieval Christians fulfilled a call for penance, which was especially important during the Lenten season. On Ash Wednesday, in the Middle Ages as it is now, a celebration of Mass incorporated the distribution of blessed ashes on the foreheads of believers. When dispensing the ashes, the celebrant reminds those receiving it that “as you are from dust, from dust you shall return” (based on Genesis 3:19).

The Index records three examples in manuscript illumination of the distribution of ashes. Each begins a part of a liturgical book read for this feast: a Gradual fragment in Princeton University Library (Kane 13), a Gradual in the Morgan Library (M.933), and a Missal in the Walters Art Museum (W.174). The Morgan and Princeton Graduals begin with the same Latin Introit, “Misereris omnium domine et nichil odisti eorum…” (Thou hast mercy upon all, O Lord, and hatest nothing…). It is interesting to note that the subject heading “Scene, Liturgical: Distribution of Ashes” used by the Index now was not in the original card file but was developed sometime during the last twenty years when post-1400 material was incorporated into the Index.