Please save the date for the next Index of Medieval Art conference, “Art and Proof in the Ninth Century.” Organized by Professors Beatrice Kitzinger and Charlie Barber in collaboration with the Index and co-sponsored by the Department of Art & Archaeology, the conference will follow on the department’s 2025 Kurt Weitzmann Memorial Lecture by Francesca dell’Acqua (Università di Salerno) on December 5, which will double as the conference keynote.

The springing point of the conference is December 825, when the city of Paris witnessed a synod devoted to the discussion of the status of images in the Carolingian world. This meeting, convened in response to flare-ups of the “image question” in Constantinople and Rome, set forth a Latin Christian understanding of images that would remain dominant in early and high Medieval Europe. The dossier affirmed the value of images as mnemonics and devotional aids but ultimately re-asserted the primacy of verbal media in the religious sphere. However, as the conference speakers will show, artistic evidence itself suggests that ninth-century approaches to the role of images complicated and exceeded those prescribed for them by the bishops at Paris.

Prof. dell’Acqua’s lecture will directly address the Roman–Frankish context in which the Paris synod unfolded. The papers that follow will dramatically expand the lens through which we view the central questions by considering the notion of proof in the ninth century through a much wider lens, reaching from the British Isles to Japan and from Georgia to Egypt and representing a wide range of languages and religious communities. Key themes include: the terminology surrounding images and their uses; questions of representation, semiotics, authenticity and truth; propositions that need proving and their modes of proof; the functions and status of images in society, and how these are secured; how occasions for image discussion reflect on local circumstances and priorities; ways in which discussing the validity of images intersects with politics, diplomacy, or self-fashioning; whether the notion of proof in relation to images, which emerged from a specific Christian and European moment, resonates in other contexts; and whether a more global perspective provides different valences for the concept of “proof” through artwork.

Francesca Dell’Acqua [Weitzmann Lecture, Dec. 5, 2025] Associate Professor, Università di Salerno

Andrea Achi, Associate Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Nourane Ben Azzouna, Associate Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anouk Busset, Lecturer, Université de Lausanne

Zsuzsanna Gulacsi, Professor, Northern Arizona University

Rachel Saunders, Assistant Professor, Princeton University

Ephraim Shoham-Steiner, Associate Professor, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Erik Thunø, Professor, Rutgers University

Anca Vasiliu, [Respondent] Director of Research, CNRS, Sorbonne Université

About 45 people attended the hybrid session sponsored by the Index of Medieval Art at the 60th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, MI on May 8, 2025. “Breaking the Mirror: New Approaches to the Study of Medieval Images” asked scholars in all fields to think afresh about what they can learn from medieval images, and especially how their potential to go beyond mere illustration—to aspire, deceive, and even fantasize—complicates what and how medievalists can learn from them. The session roster included:

“Byzantine Images and Religious Truths: A Wide-Angled View.”

Diliana Angelova, University of California–Berkeley

“The Imago agens in the Illumination of the Luttrell Psalter: Expressing the Ineffable that Is Beyond Words.” Christina Caroline ten Wolde-Marshall, Independent Scholar (Wales)

“Portrayals of the Patriarch: The Pictorial Slander and Celebration of Ignatios.”

Lora Webb, Emory University

The three papers provoked a lively discussion and a dynamic start to the three-day conference. Hearty thanks to our three speakers and their audience, both in person and online!

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2025.

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to introduce a new AI assistant to support users in their research on medieval iconography. The new IAI (Index Artificial Intelligence) aims to save researchers time and energy by aggregating search results into a digestible single image for use in your research paper or article. No more online filters to manipulate, index drawers to pull out, or search results to sort: simply tell IAI what you’re looking for and it will deliver an image that distills all the essential features of your search terms into the quintessential example for your next research project. And because it’s AI generated, no one will worry about copyright permissions.

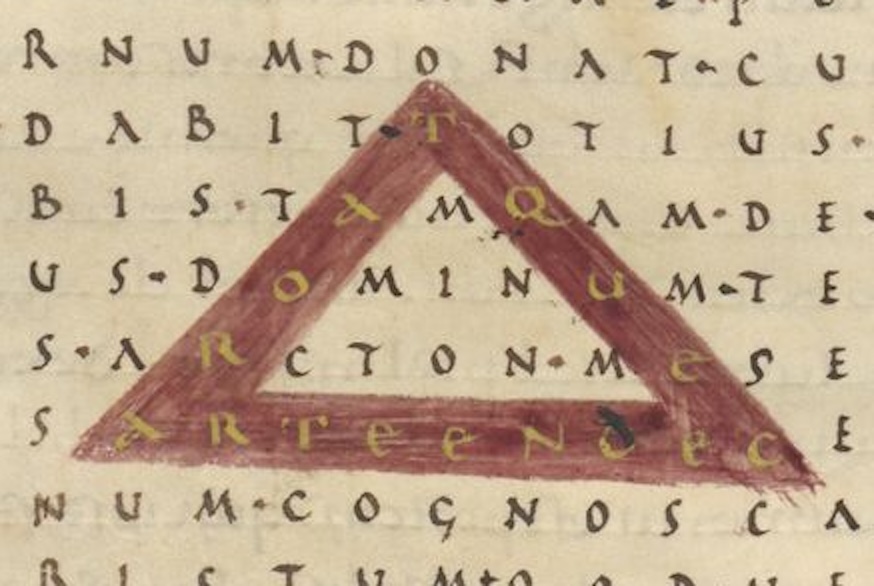

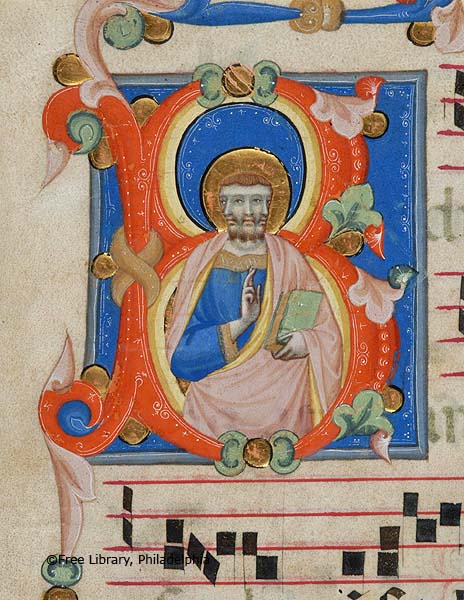

Perhaps you’re looking for a traditional inhabited initial in a musical manuscript, say a representation of the blessing Christ inhabiting the initial B of “Benedictus.” You could of course search for existing images in the traditional way, using the Subject term “Christ, Blessing” or an Associated Text using an incipit like “BENEDICTA SIT….” That could yield a lot of search results! But who wants to comb through those? Let IAI do the job for you, and you could get something like this:

Here, nested cozily in a bright vermilion letter B with all the right kinds of leafy decoration, is a generously robed figure of Christ holding a book as he raises his hand in blessing. Is it perfect? Well… you know how sometimes figures in AI art come out with a couple of extra fingers, or arms, or maybe even faces? Let’s just say we’re still working out a few things.

In the meantime, maybe you’re interested in legendary beasts and looking for a medieval depiction of a fierce mythological animal, say one that uses massive horns and fire to defend itself from attackers. IAI has got you covered! Of course, you could dig around in the Subject Classifications network to see all the different kinds of animals you can actually find in the Index of Medieval Art, maybe checking out the “Mythological and Religious Creatures” category to find your fiery friend. But searching on your own is so old school. Let IAI do it for you! We know you’ll like what you see.

Big horns: check! Fire: check! Attackers repelled: check! Oh wait, you wanted the fire coming from its mouth? How was IAI supposed to know that? Maybe you should have searched on your own for this one, using the Subject term “Dragon.”

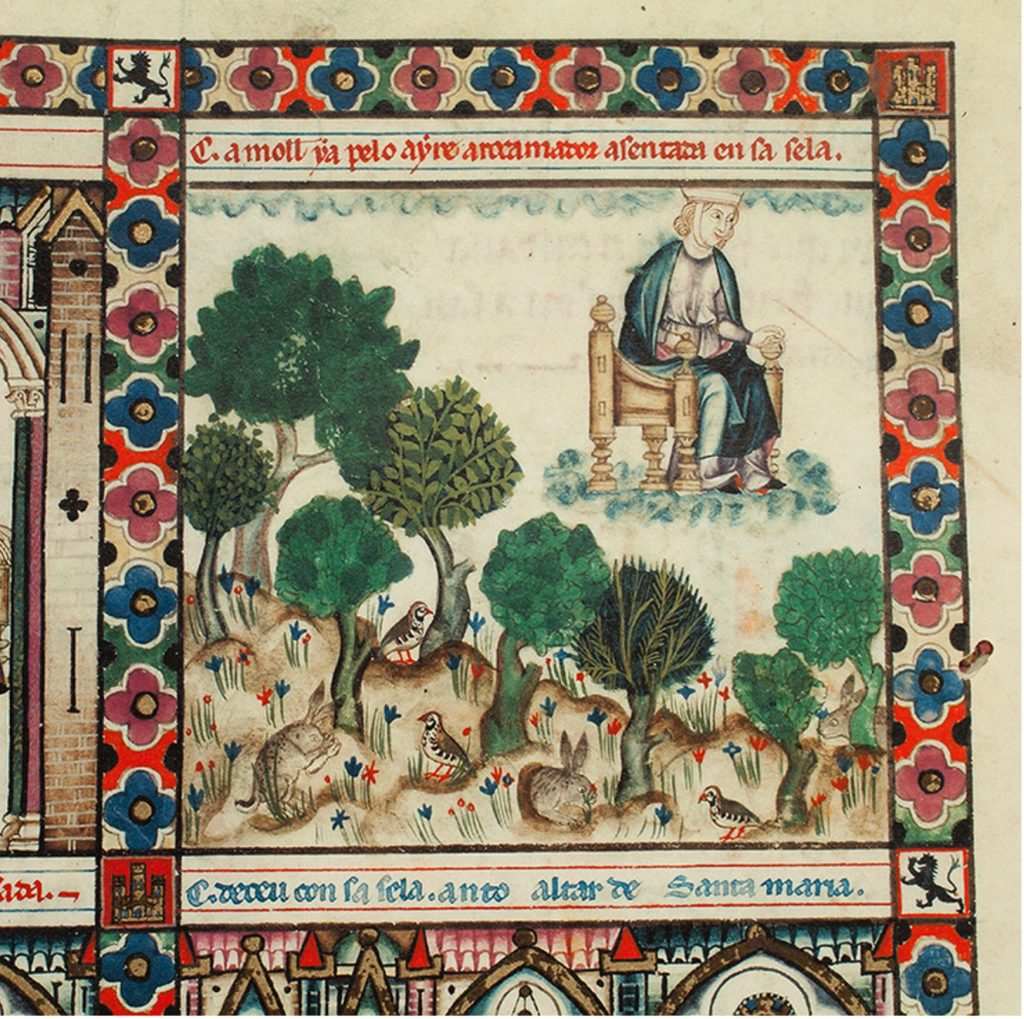

Let’s try something a little simpler. How about a medieval pilgrim? Pilgrimage to sacred sites, whether for penitence or to show devotion, was so important to medieval people that you won’t be surprised to learn there are more than thirty Index Subjects starting with “Pilgrim” in the database. But do you really want to take the time to look at all of those and then have to make decisions about which ones best suit your research needs? IAI has got your back. Let’s make it authentic by narrowing the parameters: we’ll ask for a female pilgrim on her way to the shrine of Our Lady of Rocamadour.

That’s a lady pilgrim all right, and the captions tells you she’s definitely on the way to Rocamadour. Yes, it does seem a little unusual that she’s flying there in a chair instead of riding a donkey, but of course if you’d wanted that kind of detail, you would have used the search filters for a Boolean search of the Subjects “Pilgrim” and “Donkey.” But since when were donkeys so important? IAI thinks this is a terrific way to go. You’ve never heard of armchair travel?

Even if IAI still has a kink or two to work out, we think you’ll love what it can do for you. Mental energy is precious; why devote so much of it to original image research when you can harness multiple terabytes of data and enough electricity per search to fully charge your phone just so IAI can come up with one fantastic image like these? Is IAI easy? You bet. Is IAI fun? Tell us, who doesn’t love flying chairs and flaming poo? Is IAI responsible? Now why would you ask us that? It’s not a self-driving car.

As friends and colleagues around the world prepare to celebrate festivals of light, we at the Index wish you all a luminous holiday season and a peaceful, fulfilling New Year.

This year we’re inspired by the global interest in Index resources, which has grown considerably since we ended our yearly database subscription fees in 2023. Our last online database training session saw individual registrations from more than ten different countries, including Australia, Greece, Spain, Ireland, the UK, Italy, China, and Canada. Interchange with this wide network has been a highlight for us.

In 2024, we also offered online database tutorials, hosted classroom visits, and fielded more than one hundred research questions in person and online. Such interaction is at the core of the Index’s long history as a research tool and hub for scholarship in medieval art history. We here offer a selection of the highly varied questions asked of the Index in 2024:

Please continue to stay in touch. Follow us on Facebook and Bluesky; use our Research Inquiries form; and watch our blog for new events in 2025. Next year’s happenings include an online database training session, an Index Wintersession class on writing alternative text for images, the conference session “Breaking the Mirror” at the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, and a fall conference on “Art and Proof in the Ninth Century.” We look forward to sharing these events with you and to supporting your research for many years to come!

Free registration is now open for on-site attendance at the Index conference “Unruly Iconography?” In it, eight speakers from a variety of fields will open new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules, challenging their listeners to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided when iconographic motifs should be considered canonical and which are instead “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” They will interrogate the value and limitations of the unspoken binaries that often underlie such labels: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, or center versus periphery. Their wide-ranging papers will demonstrate the value of a more critically aware, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

The conference will take place on November 9, 2024 in the Louis A. Simpson Building, A71, at Princeton University. Although the conference will not be recorded, a live stream link will provide digital access to those who cannot attend in person. Those planning to attend on site are asked to register to ensure adequate seating and refreshments.

Please find the full conference schedule and registration link here. We look forward to seeing you!

Many people know the name of Belle da Costa Greene, if not also her story as the fledgling librarian who rose to become librarian and then director of the famous Morgan Library & Museum in New York (1905–1948). A major exhibition opening this fall at the Morgan will explore the broad scope of Greene’s life and career, including the challenges she faced as a young woman of African-American heritage who lived as white in a field dominated by powerful European and American men. But where did Greene acquire the training in languages, history, and rare book studies that would advance her career? With the support of the Princeton Histories Fund, a team of researchers from Princeton University Library and the Index of Medieval Art set out to learn more. Their findings include the discovery of Greene’s hand in library records, a letter pinpointing the beginning of her work with the Morgan in summer 1905, and a fascinating correspondence documenting her continuing professional relationship with Princeton faculty and staff after her departure for New York.

These findings will be highlighted in a mini-exhibition opening on November 12, 2024 at Firestone Library and beginning with a round table discussing the project’s findings and their ramifications for Greene’s biography and the history of librarianship. Featured participants will include Kathleen Brennan of Princeton’s Mudd Library; Erica Ciallela of the Morgan Library & Museum and Schlesinger Library, Harvard University; and Mireille Djenno of Firestone Special Collections. The round table will be held at 4:30 pm on Nov. 12 in the Chancellor Green Rotunda, the very building in which the university’s library was housed during Greene’s time at Princeton. It will be followed by a reception and viewing in Firestone Library. Both round table and exhibition, supported by the Princeton Histories Fund, are free and open to the public.

The Index of Medieval Art is delighted to share a call for participation in a field seminar hosted by the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” at the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples on 12-13 June 2025. Associated with the conference “Unruly Iconography?”, which will be hosted on 9 November 2024 at the Index of Medieval Art, “Unruly Iconographies / Iconografie Indisciplinate” will take medieval Naples and southern Italy as a laboratory for exploring relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages.

The seminar organizers welcome proposals that consider individual case studies from medieval Naples and southern Italy as points of departure for investigating questions including so-called exceptions, hapaxes, mistakes, and lost originals; dynamics between “center” and “periphery”; challenges of chronology and dating in so-called peripheries and border zones; circulations of iconographies through polycentric cultural networks; translations of motifs across mediums, formats, functional contexts, and audiences; the legibility and illegibility of iconographies across cultures; mechanisms of transfer including mobile artworks, artists, and patrons; interplays between royal, non-royal elite, and non-elite patronage; and the limitations of previous models of iconography when confronted with cases in medieval Naples and southern Italy. They welcome in particular proposals that locate southern Italy within broader Mediterranean worlds, at the convergence of multiple cultural and religious currents including Latin and Orthodox Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

Further details and a compete call for papers are found here.

The Index of Medieval Art will sponsor the session “Breaking the Mirror: New Approaches to the Study of Medieval Images” at the 60th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo.

Everyone wants something from medieval images: a sense of story, a corroborated argument, a witness to medieval realities. Although the methods by which scholars seek these answers have evolved considerably, their work remains dominated by the conception of the medieval image as mirror, one that reflects either explicitly or indirectly the truths of the historical past. This session challenges this tendency by asking what we can really expect to learn from medieval images. How does their potential to go beyond illustration—to aspire, deceive, and even fantasize—complicate what and how scholars can learn from them?

We invite papers from researchers at all levels and especially encourage submissions from early-career scholars. The session’s hybrid format can accommodate up to two remote participants. Conference details and a full call for papers can be found at this link.

“Unruly Iconography?” opens a new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules. Its eight speakers will challenge their listeners to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided when iconographic motifs should be considered canonical and which are instead “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” They will interrogate the value and limitations of the unspoken binaries that often underlie such labels: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, or center versus periphery. Their wide-ranging papers will demonstrate the value of a more critically aware, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

“Unruly Iconographies?” will take place on November 9, 2024 and constitutes the first of two internationally linked conferences, the second of which will be a site-based seminar at the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” in Naples in June 2025, which makes southern Italy a laboratory for exploring the relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages.

Speakers for the conference are listed alphabetically below. A schedule and free registration link will be shared on this page in September 2024.

Diliana Angelova (UC Berkeley), “Lawless, Hilarious, Black: Eros and Companions in Byzantium.”

Alexander Brey (Wellesley College), “Iconography Between Empires: The Red Hall at Varakhsha.”

Heidi Gearhart (George Mason University), “A Poem, a Scribe, a Saint, and a Scriptorium: Evoking Multiple Presences in Arras Bibliothèque Municipale MS 860.”

Julie A. Harris (Independent Scholar, Chicago), “Indicate, Illustrate, Decorate, or Comment? Iberian Hebrew Bibles and Their Unruly Paratextual Marks.”

Krisztina Ilko (University of Cambridge), “The Chessmen of the Hunt.”

Nicole C. Paxton (John Cabot University), “Iconographic Innovation and Political Subversion in the Medieval Serbian Akathistos Cycle.”

Patricia Simons (University of Michigan/University of Melbourne), “The Goldfinch: Flights of Fancy.”

Mark H. Summers (University of Arkansas), “Dressed to Impress: Reconsidering Roger II of Sicily and the Iconography of Kingship.”

Modern study of medieval iconography inevitably entails grappling with exceptions and the rupture of expectations. No sooner might scholars settle on an expected visual formula—Cain killing Abel with his farmer’s hoe, Saint George riding his snowy steed—than we’re pulled up by an image that flouts those rules. In the fifteenth-century Alba Bible, Cain sinks his teeth directly into his brother’s neck, arguably in reference to Jewish exegesis, while in some Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons of St. George, a small boy carrying a cup rides with the saint, inspiring a semi-serious modern tradition concerning George’s love of coffee. Other iconographic traditions seem to emerge out of the blue, as did the distinctive type known as the Virgin of Humility, which flowered suddenly in Mediterranean cities in the 1340s. Such unruly iconographies both intrigue and disappoint us: they engage yet disobey our expectations, and we are left to wonder why.

The culprit in such cases is less often a rogue medieval work of art than the rigidity of modern scholarship. Despite ample evidence to the contrary, the assumption that medieval iconographic norms were formulaic, authoritative, and above all universally obeyed still shapes the way modern scholars analyze the imagery they study. Even after the poststructuralist turn, art historians have continued to wrestle with expectations deeply embedded in the discipline: that medieval artists preferred to copy or turn to text rather than to innovate; that unprecedented iconography must be based on a lost original; that patrons or learned advisors must have directed artists’ work; that traditions translated smoothly across media, formats, and contexts; that all viewers read and understood the images they saw in the same way. Underlying many of these assumptions has been a wider one: that the ideas of greatest value must be tracked to artists rooted in cosmopolitan centers, rather than to artists and works of art that circulated freely throughout their peripheries.

The conference “Unruly Iconographies? Examining the Unexpected in Medieval Art” aims to open a new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules. We call for papers, drawn from any area of the medieval world broadly defined, that ask both speakers and audience to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided which iconographic motifs are canonical and which are “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” At the broadest level, we seek to problematize the binaries on which these paradigms were founded: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, and center versus periphery. At a more specific one, we invite deeply researched case studies whose particularities can lead scholars to a more effective, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

“Unruly Iconographies?” will take place on November 9, 2024 at the Index of Medieval Art at Princeton University, following the Weitzmann Lecture by Dr. Brigitte Buettner, held on November 8 and hosted by Princeton’s Department of Art & Archaeology. It also will constitute the first of two internationally linked events, the second of which will be a site-based seminar at the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” in Naples in June 2025. Whereas the Index conference will consider broadly disciplinary questions about methodology, theory, and models, the Naples conference, hoped to be the first of several site-based conferences of this kind, takes southern Italy as a laboratory for exploring the relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages, focusing on the potentials and limits of the study of iconography in southern Italy. Details about this conference will be available in Summer 2024.

Submissions for the Princeton-based conference are invited by April 1, 2024. They should include a one-page abstract and c.v. and be sent to fionab@princeton.edu. Travel and hotel costs for the eight selected speakers will be covered by the Index. Speakers will be informed of their selection no later than May 1, 2024.