The Index of Medieval Art wishes all our faithful blog readers a joyful New Year! Whether you are currently recovering from the excesses of New Year’s Eve, eating certain foods that bring good luck, contemplating a new exercise regime (that you will abandon by Groundhog Day), or arguing with your most pedantic family member (unless that happens to be you) over when the new decade really begins, we Indexers would like to take the time to examine some medieval New Year festivities for your reading pleasure today.

For the Valois courts in late medieval France, the new year was celebrated by partaking in the étrennes, an annual gift-giving ritual with roots in Roman Antiquity. Originating from the Latin strena, the term étrenne encompassed both the ritual act of gift giving as well as the actual gifts themselves.[1] Thus, on New Year’s Day the highly dysfunctional yet fashionable members of Valois nobility gave one another exquisitely-made, begemmed objects known as joyaux. Few of these resplendent pieces are extant today, but Valois inventories preserve a wealth of information on the kinds of items that were presented for the étrennes and the identities of their original donors and recipients.

The only surviving non-manuscript étrenne is the Göldene Rössl, a multifigured masterpiece of fifteenth-century Parisian gold- and enamelwork. Positioned atop a golden platform, the Virgin and Child loom large beneath a gem-encrusted trellis, towering over delicate representations of infant saints and the kneeling figures of King Charles VI and a knight. Below this assemblage stands a small, white horse led by a page in elegant clothing.

Beyond its obvious material value, the Göldene Rössl also serves as one of the finest examples of émail en ronde bosse, an enamel technique that showcases varying gradations of color and translucency. Presented by Isabeau of Bavaria to her husband Charles VI on New Year’s Day in 1405, the object exemplifies the kinds of sumptuous objects exchanged by members of the Valois courts for the étrennes.

The kneeling figure of Charles VI venerating the Virgin and Christ Child exudes a sense of decorum, sanctity, and solemnity that belies the reality of the ruler’s frequent bouts of madness described in early fifteenth-century sources. The Index includes other portraits of the king, identified within the database as the subject Charles VI of France. Other notable Index Valois subjects include Philip the Bold; Charles V of France, the Wise; and, of course, John, Duke of Berry (Jean de Berry). Curiously enough, the most famous portrait of the duke of Berry, namely, the January calendar page of the Très Riches Heures, does not show a representation of gift exchange. Nevertheless, the luxurious metalwork on display and the sartorial finery of the duke and his courtiers depicted in the illumination underscore the absolute lavishness of the New Year’s celebrations.

Lest we assume that bad gift-giving behavior developed in the modern world, consider the documented foibles of the Valois nobility. For those of us who feel guilty about splurging on items for ourselves during the Black Friday sales, take comfort that Louis of Orléans gave himself a fabulous sword “in the Venetian style,” ornamented with gold and precious stones, one New Year’s Day, or that during the étrennes of 1404, Philip the Bold gifted himself an exquisite gold nef (ship model) covered in gems and pearls that cost a minor fortune.[1]

Have a friend or family member who likes to give you weird “joke” gifts for Christmas or Hanukkah? The Limbourg brothers crafted a fake book for Jean de Berry made from a single block of wood affixed with a faux binding and clasp. Hilarity must have ensued when their illustrious patron attempted to open the trompe l’oeil volume in front of other members of his court on the first of January in 1411.[2]

Forget to buy something for that special someone in your life? Jean de Berry’s wife Jeanne de Boulogne remained, as Michael Camille astutely observed, “notoriously absent [emphasis mine] from the ‘give and take’ of the inventories” that carefully recorded all of the gifts presented during the annual festivities.[3] The duke of Berry also habitually committed the common sin of regifting. As the duke’s inventories attest, many of the joyaux that he received during the étrennes were later regifted to other individuals or were even melted down for the creation of new objects. Nor was he the only member of the family to do so, and even the Göldene Rössl met a similar fate. Only a few months after receiving the piece, Charles VI (always low on funds) pledged it to his brother-in-law Louis of Bavaria as a partial payment for his annual pension![4]

In spite of the depressing historical realities surrounding these ostentatious objects, they will always have a hold on the modern imagination. And why not? The future is golden, dear readers. Happy 2020!

[1] Buettner, “Past Presents,” 608, 623, n. 71.

[2] Michael Camille, “‘For Our Devotion and Pleasure:’ The Sexual Objects of Jean de Berry,” Art History 24, no. 2 (2001): 181.

[3] Camille, “‘For Our Devotion and Pleasure,’” 180.

[4] Buettner, “Past Presents,” 607. For a more in-depth analysis on the creation and history of this amazing object, see Reinhold Baumstark and Renate Eikelman, eds., Das Göldene Rössl: Ein Meisterwerk der Pariser Hofkunst um 1400 (Munich: Hirmer, 1995).

Contributed by Catherine A. Fernandez, Art History Specialist.

As the calendar approaches the winter solstice, our thoughts turn to Saint Lucy, whose feast day on December 13 shares many of the same themes of light and hope. A modern viewer’s first encounter with medieval images of the early Christian saint Lucy might seem somewhat gruesome. The Index holds 139 records with the subject Lucy of Syracuse, and in many, as you will notice, she is represented holding a dish or tray bearing two eyes (Fig.1). This peculiar attribute derives from her hagiography, in the course of which the saint’s eyes were gouged out.

The narratives related to this eye-gouging seem to have developed only in the later Middle Ages, and they are inconsistent: some recount that her Roman persecutors tore her eyes out as part of her martyrdom; others claim that she herself did it to present them to an unwelcome suitor who admired her beauty—take your pick!

In case you were wondering—and those of you who are acquainted with fourth-century martyrs will probably have already guessed it—in neither version of the story was eye-gouging the cause of Lucy’s death. As is almost always the case in such stories, after several other tortures, her head was cut off. This leads us to the other way Lucy is often represented, either holding a dagger or with a dagger thrust into her throat (Fig.2).

But there is much more to the Lucy story than martyrdom details. According to her vita, Lucy was an early Christian during the reign of Diocletian. She decided to devote her life to God and leave her inheritance to the poor. But without her knowing, Eutychia, her mother, had already arranged her marriage. When she called off the wedding, her suitor was indignant (no surprise there) and in revenge reported her as a Christian to the Roman authorities. Although this part of Lucy’s life is less often represented than her martyrdom, some images of this period were also produced. An example is the Index subject Lucy of Syracuse, Giving Dower to Poor. As depicted by Giovanni di Bartolommeo Cristiani (active 1367–1398), Lucy appears flanked by Eutychia (Fig.3). Her left hand reaches into a decorated purse, while with her right hand she offers a coin to a man leaning on a crutch and cane. He is followed by a veiled woman and five men, all wearing hats, one with an arm in a sling and a wooden leg, and two holding canes, one probably blind. All, presumably, will be the beneficiaries of Lucy’s generosity.

Having heard that Lucy was a Christian, Paschasius, the Governor of Syracuse, commanded that she be brought to a brothel for prostitution. But when the guards tried to seize her, her body became too heavy to be lifted. In response they decided to tie her to several oxen to drag her, but she would remain immobile. This is the episode represented by Bartolo di Fredi Montalcino in the second half of the fourteenth century (Fig.4). Paschasius, seated and crowned, is at the far left, while Lucy stands at the center of the composition, with her tormentor behind her; she is tied with ropes to three oxen and a group of men trying desperately to make her move.

Since she was unmovable, her attackers next decided to cut bundles of wood and burn her alive. Although this might have seemed a solid choice, it also failed: Lucy remained unscathed and unburned. Eventually, as represented in the illumination for her feast day in the Menologion of Basil II (976–1025), she was martyred by sword in ca.304, in Syracuse in Sicily (Fig.5).

In addition to the Index subject Lucy of Syracuse, Martyrdom, Saint Lucy can also be found tagged with subjects Martyrdom, by Beheading and Sword (Martyrdom Instrument). Yes, at the Index we like to be thorough! If you’re interested in learning more about how martyrdom was represented in the Middle Ages, you can find all martyrdom types in the Index Subject browse list, where you will find instances of martyrdom by boiling oil, disembowelment, dragging by horse, and hanging by hair, for example. If searching for the instruments, you also can go to our Subject Classification and click Religious Subjects > Christianity > Saints > Martyrdom Instruments.

But enough about martyrdom. Medieval and modern devotion to Saint Lucy is deeply tied to her name: Lucia in Latin, which shares the root luc with the Latin word for light, lux, and by extension with sight. Because of this connection, she is often shown with a torch or a burning lamp, as in this thirteenth-century panel painting, today in the Musée de Grenoble (Fig.6). Lucy appears here richly dressed as a Byzantine empress, wearing a crown with precious jewels and pendula of pearls, and holds a lighted lamp in her right hand. She is flanked by two winged angels swinging censers, emerging from above. On the foreground, to the left, the female donor, Angila Cerroni, veiled, kneels with her joined hands raised in prayer.

Just like Angila Cerroni, many other devotees found themselves invoking Lucy against blindness, eye disease, sore throat, fire, and poverty; penitent prostitutes also called on her. Perhaps because Lucy’s feast day, December 13, originally coincided with the winter solstice, marking the shortest day of the year, she is especially celebrated in the Northern Hemisphere. In Scandinavian tradition even today, the oldest daughter in the family may dress in white and wear a crown of candles on her head, bringing light, just like Lucy, in the darkness of winter.

Contributed by M. Alessia Rossi, Art History Specialist.

We have recently learned of an incident that occurred at the reception following the recent Index conference “Art, Power, and Resistance in the Middle Ages,” during which an attendee not affiliated with Princeton University behaved uncivilly and aggressively toward another individual. The attendee’s remarks targeted the individual’s identity in a way that was inappropriate in any context. We wish to make it clear that conduct of this kind will not be tolerated at any event sponsored by the Index of Medieval Art.

Our recent conferences have encouraged speakers to address those ways in which the study of medieval images and ideas might shed light on contemporary social, cultural, and political issues, and several have done so. Their presentations might surprise, or even provoke intellectual discomfort in, any of our listeners. But as medieval scholars themselves well recognized, discomfort and learning often go hand in hand, and it is by exploring the sic et non of differing points of view that we move knowledge forward. Attendees at Index conferences should always feel welcome to raise questions that express disagreement with a speaker during Q&A, but both there and in all conference events, they are expected to maintain the same civil and respectful standards of discourse that are the norm in our profession, as outlined by such organizations as the International Center of Medieval Art (http://www.medievalart.org/about-us) and the Medieval Academy of America (https://www.medievalacademy.org/).

Any attendee who wishes to share a concern about the topic or content of a lecture given at an Index conference may do so by contacting the Index director, Pamela Patton, at ppatton@princeton.edu.

If you celebrate Thanksgiving in the United States, decorations for the feast might well include a representation of a cornucopia, a literal “horn of plenty” (Latin cornu + copiae) spilling over with fruits, vegetables, and flowers suggestive of a generous harvest. Wondering where this symbol came from and how it got onto Aunt Marian’s Thanksgiving table? Wonder no more: armed with 139 online records for the subject “cornucopia,” the Index is here to help.

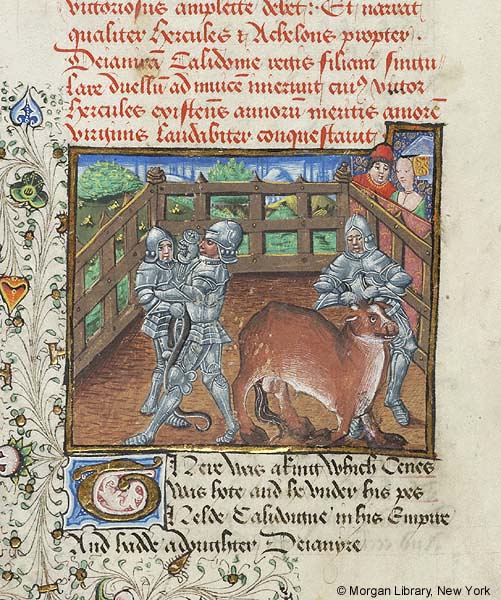

The cornucopia originated in classical mythology, where it bore connotations of plenty and good fortune. Explanations of its origins vary: according to Ovid’s Metamorphoses (ix.8), the Greek demigod Herakles tore the horn from the head of the shapeshifting river god Achelous, whom he wrestled to win the hand of Achelous’s daughter Deianira. Heracles then gave it to the Naiads, who turned it into a horn that produced an endless supply of foodstuffs. The Index records include an engagingly “modernized” version of this scene in a fifteenth-century manuscript of John Gower’s Confessio Amantis now in the Morgan Library (Fig. 1). Several other ancient sources attribute the horn to the goat Amalthea, which suckled Zeus on Crete when he was hidden there by his mother Rhea from his child-eating father Cronus. When Zeus accidentally broke off one of the goat’s horns, it became imbued with the power to be filled with whatever the owner might desire.

The positive connotations of the cornucopia made it a popular classical attribute. Usually configured as a twisted horn from which fruit, flowers, or other plants emerged, it became associated with a number of deities and personifications, including Demeter, Gaia, Persephone, and Tyche, the Roman Fortuna. A Roman statue of Tyche-Fortuna from the first or second century CE, today restored with the portrait head of an unknown woman (Metropolitan Museum of Art), portrays the goddess holding a ship’s rudder, alluding to how fortune steers human fate, in her right hand and a cornucopia filled with fruit in her left (Fig. 2).

A rendering of Fortuna with these attributes also can be found in a fresco from the synagogue of Dura Europos, produced by 244 CE (National Museum of Damascus). One of many classical references found in these early Jewish wall paintings, it appears as a faint line drawing on the right lower panel of the central door (Fig 3). In both these cases, the overflowing horn suggests a hope for the abundance that comes from good fortune.

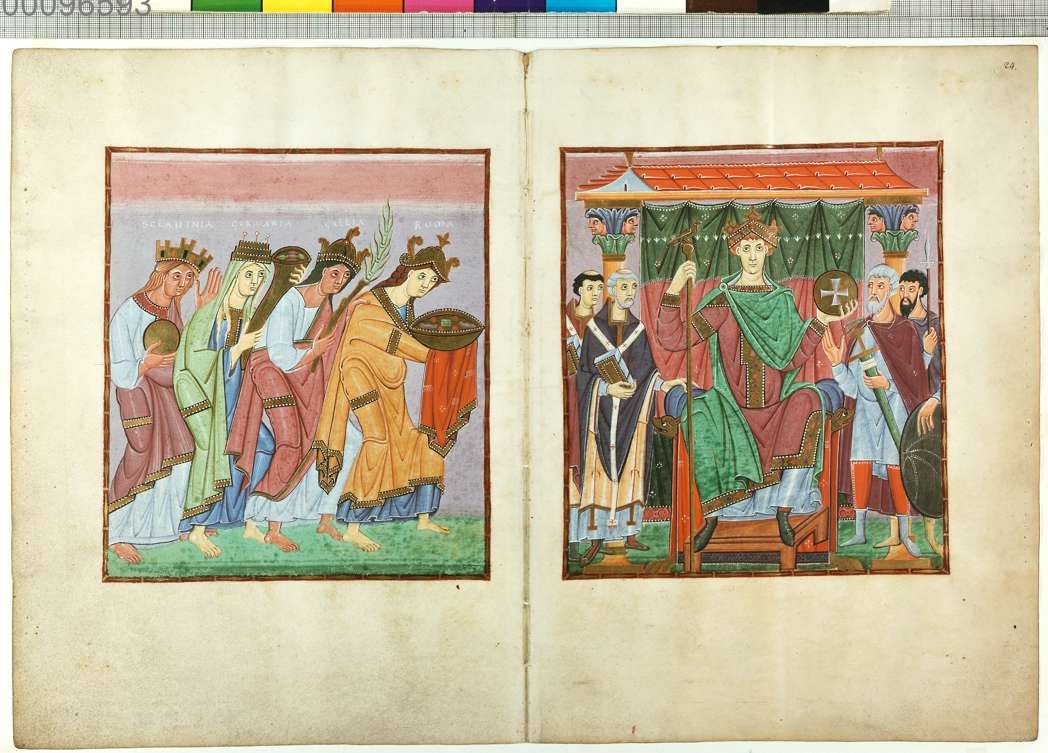

During the Middle Ages, the symbolic associations of the cornucopia expanded significantly. While it could continue to promise good fortune, it also appeared as a sign of homage, as in the Gospels of Otto III, produced in the Holy Roman Empire around the year 1000 (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek). Here, the four personified provinces who bring tribute to the emperor include a personification of Germania holding a golden cornucopia (Fig. 4); although no fruits are visible, its implications of earthly abundance would have made it an appropriate offering for the imperial ruler.

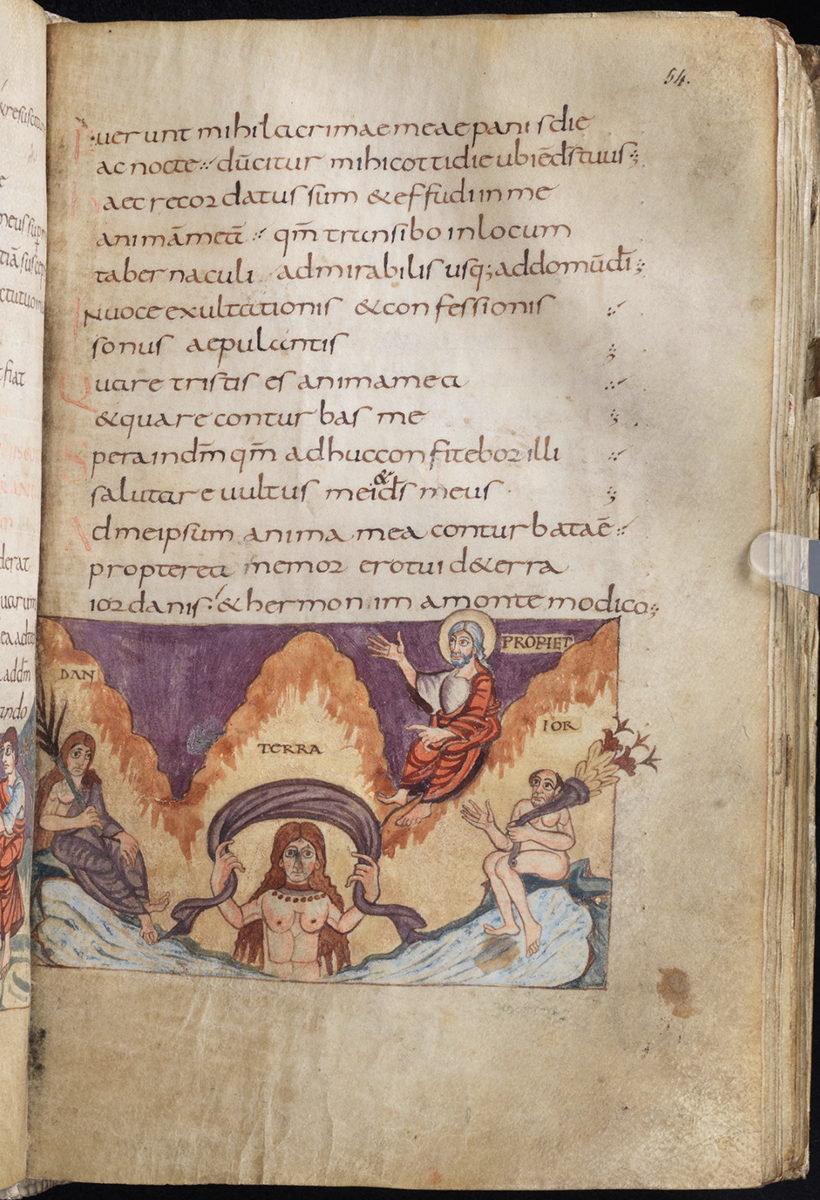

The cornucopia can also be found as an attribute of personified geographical locations, such as cities or waterways. On the right-hand leaf of a fifth-century diptych representing the cities of Rome and Constantinople (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), the figure representing the Byzantine capital holds a large cornucopia in her left hand (Fig. 5); in the Stuttgart Psalter (Württemburgische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart), the personified river Jordan holds a cornucopia sprouting leaves and flowers (Fig. 6).

The cornucopia could also represent more abstract values, including charity, hope, and abundance itself. The portrayal of Abundantia as a lesser goddess who holds a cornucopia originated in Roman tradition, and it persisted throughout the Middle Ages as a secular personification with very similar iconography.

In the early modern era, the formula was further popularized by artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, whose majestic red-robed Abundantia, painted circa 1630, spills an array of apples, grapes, figs, and other fall fruits from a cornucopia to the ground, to the delight of the putti who scramble for them at her feet (Fig. 7). This may be the formulation of the horn of plenty most familiar to modern viewers, for whom a cornucopia centerpiece suggests both the gratitude for good fortune and the spirit of generosity that both stand at the core of the modern Thanksgiving holiday.

Registration is now open for the Fall Index conference, “Art, Power, and Resistance in the Middle Ages,” November 16, 2019. To view the speakers and schedule and link to the registration form, please click the link below.

As always, Index conference admission is free and open to the public; your registration is appreciated to ensure adequate seating and refreshments. https://ima.princeton.edu/conferences/

Detail, Arch of the Transfiguration Apse Mosaic, 6th century.

Church of the Transfiguration, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt

Location, Location, Location: In-Situ Iconography within the Medieval Built Environment

55th International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo MI, May 7-12, 2020

Proposal Deadline: September 15, 2019

Please consider submitting a paper to the next Index-sponsored session at the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo! This year’s session concerns the role of iconography within the built environment and has been organized by Index specialist Catherine Fernandez.

Session description: Almost all architectural components in the Middle Ages had the potential to bear images. Walls, arches, portals, domes, capitals, and other structural supports proffered surfaces for the deployment of narratives, portraits, drolleries, and ornament. Iconography in such locations not only figured prominently in relation to ephemeral occurrences, such as the performance of the liturgy, processions, and other civic rituals; it also underscored more permanent demarcations within urban cityscapes and rural landscapes by recalling specific events or established cultural or environmental conditions, both historical and legendary. This session invites proposals that explore the integration of in-situ iconography within the medieval built environment. We welcome papers that consider the relationship between the location of imagery within a monument and related external factors such as ritual, topography, patronage, institutional or civic memory, and regional identit(ies). Papers may consider specific case studies or address more theoretical concerns.

Please send abstracts of no more than 300 words with a completed Participant Information Form (https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/submissions) to caf3@princeton.edu) by September 15, 2019.

Further information about the Congress can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress

Information on awards granted to defray the travel costs of speakers can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/awards

Please join the Index of Medieval Art for a one-day conference that examines the role of the visual in the negotiation of medieval power relationships, whether political, social, religious, or individual. Eight scholars with a range of specializations will address how works of medieval art were used to impose and maintain power over others, to resist dominant figures or regimes, or as agents in the back-and-forth of an ongoing power struggle. Speakers will include:

Heather Badamo, University of California, Santa Barbara

Elena Boeck, DePaul University

Thomas E.A. Dale, University of Wisconsin

Martha Easton, St. Joseph’s University

Eliza Garrison, Middlebury College

Anne D. Hedeman, University of Kansas

Tom Nickson, Courtauld Institute of Art

Avinoam Shalem, Columbia University

106 McCormick Hall, Princeton University

Organized by Elina Gertsman and Vincent Debiais and hosted at the Index of Medieval Art

Focusing on the long and rich tradition of nonfigurative art, this international symposium will explore the inception and transformation of abstraction(s) at various historical pivot points between the advent of Christianity and the interrogation of epistemological queries in the later Middle Ages. The symposium aims to introduce the concept of abstraction to the field of premodern art and redefine it as a visual structure that predicates the very nature of image-making. We seek to interrogate non-figurative forms in medieval material culture; to contextualize these forms within the contemporaneous cultural and philosophical discourses; to identify the common features that favor the emergence of abstraction specifically in the long Middle Ages; and to determine how abstraction has been used to make visible what is beyond any kind of representation. For the full schedule, click here.

Registration is free but required to guarantee seating.

The conference is co-sponsored by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the French-American Cultural Exchange Foundation, the Index of Medieval Art, Case Western Reserve University, and the École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

Eclecticism at the Edges: Medieval Art and Architecture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Cultural Spheres c.1300–c.1550

On April 5-6, 2019, the Index will co-host “Eclecticism at the Edges: Medieval Art and Architecture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Cultural Spheres,” along with the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, the Department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University, The Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Stanley J. Seeger Hellenic Fund, the Mary Jaharis Center for Byzantine Art and Culture, the International Center of Medieval Art, and the Society of Historians of East European, Eurasian, and Russian Art and Architecture. This two-day symposium focuses on the art, history, and culture of Eastern Europe between the 14th and the 16th centuries .

In response to the global turn in art history and medieval studies, “Eclecticism at the Edges” explores the temporal and geographic parameters of the study of medieval art, seeking to challenge the ways in which we think about the artistic production of Eastern Europe from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries. This event will serve as a long-awaited platform to examine, discuss, and focus on the eclectic visual cultures of the Balkan Peninsula and the Carpathian Mountains, the specificities, but also the shared cultural heritage of these regions. It will raise issues of cultural contact, transmission, and appropriation of western medieval and Byzantine artistic and cultural traditions in eastern European centers, and consider how this heritage was deployed to shape notions of identity and visual rhetoric in these regions that formed a cultural landscape beyond medieval, Byzantine, and modern borders.

You can view the program here.

The symposium is free, but registration is required to guarantee seating. For any queries, please contact the organizers at eclecticism.symposium@gmail.com.

NB: This satirical post was shared in celebration of April Fool’s Day 2019.

From time to time, we Indexers like to lift the veil, so to speak, on the cataloguing procedures and upgrades that we have undertaken online. One of our current priorities is filling out our Subject Authority records. These records are where researchers can find further information about a given iconographic subject, including the preferred term used by the Index for that subject and a brief description of the iconography, its main attributes, and its relevant cultural details.

We know that visitors to the database may use alternate names, spellings, or related terms for a particular subject during a search query, and we’re determined to help you find them. As we Indexers like to joke, one scholar’s Maiestas Domini is another scholar’s Christ in Majesty! (rim shot) It is for this reason that we supply a field for “See-From” terms, a list of alternate names and phrases that will redirect you to the preferred Index iconographic term.

Below is a sampling of our newest subject authority terms offered as an overview of our work methods, as well as a sense of where our field is heading with regard to iconography.

NAME: COCONUT

Note: Aural method of riding in medieval Britain that consisted of banging two empty halves of coconuts together to mimic the sound of horse hooves. Nota bene: the coconut is not indigenous to the region and likely arrived due to the migratory practices of the African Swallow.

See-Froms:

NAME: FRENCH PERSONS

Note: Surly Gallic individuals speaking with outrageous accents and serving Guy de Loimbard, possessor of “a” Holy Grail. Experts in deploying taunts at their enemies.

See-Froms:

NAME: LIVESTOCK (ARMS AND ARMOR)

Note: Favored weaponry of French Persons, comprising cows, geese, and other assorted farm animals to be hurled over castle walls.

See-Froms:

NAME: KNIGHTS WHO SAY “NI!”

Note: Darkly-clad knights wearing helmets bearing cow horns, keepers of the sacred words “Ni,” “Peng,” and “Neee-Wom.” Those who hear them seldom live to tell the tale. Lovers of ornamental garden elements that are nice and not too expensive.

See-Froms:

NAME: RABBIT OF CAERBANNOG

Note: A deceptively cuddly rabbit who is a foul, cruel, and bad-tempered thing. It guards the entrance to the Cave of Caerbannog, home to the Legendary Black Beast of Arrrghhh.

See-Froms:

NAME: HOLY HAND GRENADE OF ANTIOCH

Note: One of the sacred relics created to “blow thine enemies into tiny bits.” Instructions for its use found in the Book of Armaments 2:9–21.

See-Froms:

NAME: CASTLE ANTHRAX

Note: Castle with admittedly not a good name but possessing beds that are warm and soft and very, very big. It houses eightscore young blondes, cut off from the rest of the world with no one to protect them. These females enjoy bathing, dressing, [SCENE, OBSCAENA], making exciting underwear, [SCENE, OBSCAENA], and after [SCENE, OBSCAENA], [SCENE, OBSCAENA]. *

See-Froms:

* Note from the Editors: Given our reputation as a family-friendly blog, we have decided to redact this particular authority record. To that end, we have dusted off the Index’s trusty early twentieth-century subject heading “Scene, Obscaena.” As you readers are well aware, Latin makes everything sound more modest. The cataloguer responsible has been sacked.