NB: This satirical post was shared in honor of April Fool’s Day, 1 April, 2021

We might consider baseball as American as apple pie. Popular legend ascribes its invention to Abner Doubleday in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York, while historians of the sport point out that a similar game was played in North America as early as the late eighteenth century. Some, however, have hypothesized that the game had earlier roots in two early modern English games, rounders and cricket.

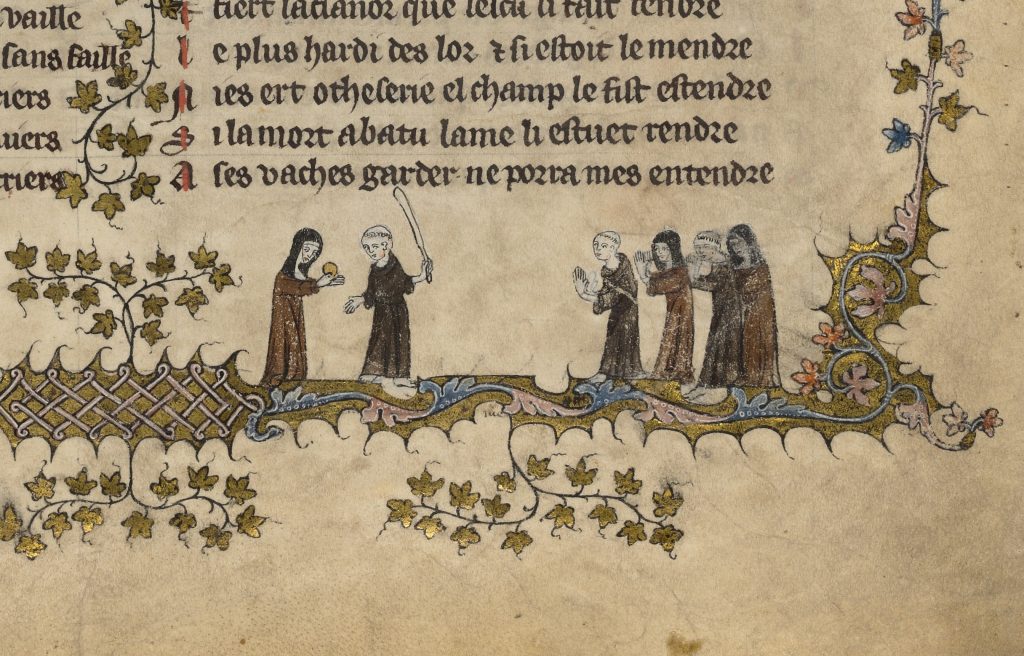

Yet there is evidence to suggest that baseball has far deeper historical roots, reaching back to the Middle Ages. The marginal decoration of a fourteenth-century French manuscript now in Oxford’s Bodleian Library (MS. 264) includes what may be the earliest conclusive illustrations of the game, played here by a group of nuns and monks. The nun at left has caught the ball just after the monk at bat has swung and missed. The monk turns to argue the count as two monks and two nuns in the infield raise their hands, ready to field, in a classic example of what Otto Pächt has called “simultaneous narrative.” The absence of outfielders in the scene was surely the result of artistic economy, given the limited space afforded by the gilded floral and foliate border, a decorative form that perhaps inspired the much later planting of ivy on the outfield wall at Wrigley Field, where players still contend with limited space.

The representation of the game’s players as cloistered religious figures offers a note of accuracy, as French nuns are in fact the earliest recorded players of the game that they called le base-bal. As early as the twelfth century, the nuns of the Abbey of Fontevraud in particular had established a reputation for their high on-base percentage and daring in run-downs; a certain Wilgefortis is lauded in conventual records for her lusty swing and reliability in the clutch. Barnstorming throughout the Loire valley, the Fontevraud nuns found the women of other convents eager to meet them between the lines, although the same could not be said of the monks and canons they challenged, most of whom refused to play, claiming the women “couldn’t throw.” The mixed-gender matchup depicted in the fourteenth-century Bodleian manuscript reflects a later era, when the dominance of the Fontevraud lineup had faded into distant memory and monks became more willing to test their skills against their slugging sorores.

Conventual baseball faded in Europe in the sixteenth century as reformers like Martin Luther turned popular opinion against the “devil’s game,” describing it as a gateway to luxury and vice and also complaining that the action was “too slow.” Today, it is only pictorial traces like that in Bodleian 264 that preserve the vibrant medieval traditions that gave us “America’s pastime.”

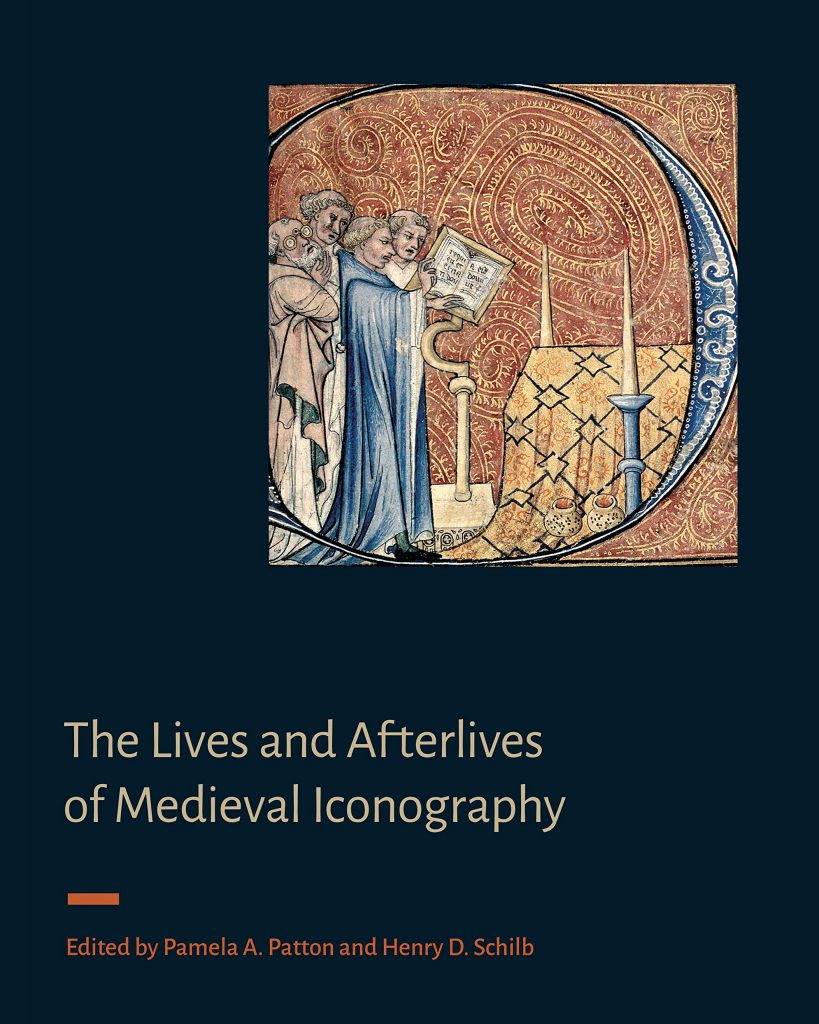

We are pleased to announce the publication of the first book in the new series “Signa: Papers of the Index of Medieval Art at Princeton University,” co-published with Penn State University Press. The new volume, The Lives and Afterlives of Medieval Iconography, is co-edited by Pamela A. Patton and Henry D. Schilb and includes contributions from Kirk Ambrose, Charles Barber, Catherine Fernandez, Elina Gertsman, Jacqueline E. Jung, Dale Kinney, and D. Fairchild Ruggles. Congratulations and thank you to all our authors!

The second volume in the series, Beyond the Crossroads: Image, Meaning, and Method in Medieval Art, is currently in production.

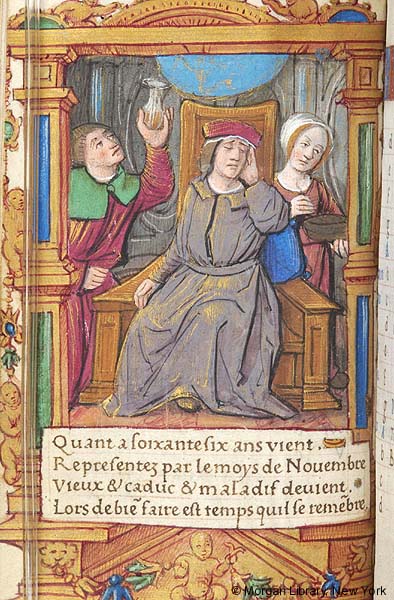

The year 2020, with its global pandemic, successive environmental crises, and sharp social and political divisions, has tested the patience, faith, and/or equilibrium of many people. As we approach the winter holidays, some will find solace in practicing gratitude—for challenges overcome, for crises averted, or simply for the love and support of those around them. It was not so different in the Middle Ages, when people in difficult circumstances also sought opportunities to consider or express gratitude, sometimes by pondering longstanding exemplars and sometimes by offering thanks of their own. Many of these left traces in medieval visual culture.

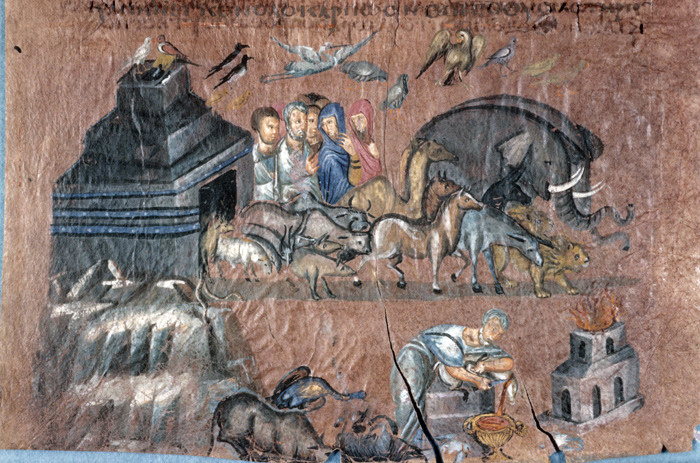

The most widely known medieval images of thanks-giving are those directed to the divine and holy figures to whom the faithful turned in troubled times. An example is the offering made by Noah after surviving the Great Flood, as described in Genesis 8:20 and represented in such works as the sixth-century Vienna Genesis [1]. In this purple-dyed luxury manuscript, the offering scene appears below a short parade of humans and animals, including elephants, lions, and camels, that issues from the ark onto dry land. Noah hunches gently over a sacrificial lamb he has placed on an altar as a thank-offering for humanity’s second chance.

A more creative expression of thanks appears in the Golden Haggadah [2], a fourteenth-century Passover manuscript in which Aaron’s sister Miriam leads the women of the Israelites in music-making and dance to thank the Lord for bringing them safely out of Egypt (Ex. 15:20–21).

Medieval Christians often gave visual thanks to the saints on behalf of those whom they were thought to have healed or rescued from danger. A thirteenth-century stained glass window in Canterbury cathedral records a number of miraculous cures performed by the relics of Saint Thomas Beckett, depicting the relieved victims of an arrow wound, malaria, madness, and even a nosebleed kneeling before the saint’s altar, their hands joined in thanks [3].

In the later Middle Ages, the Virgin Mary, thought to be the intercessor closest to God, earned special gratitude for her protection of the faithful: in the Cantigas de Santa María, the devotees who thank her for her miracles on behalf of the ill, the injured, and the unfortunate include the owner of an ailing silkworm colony, the recovery of which she celebrates by producing a beautiful silk textile that is presented to the Virgin by the king [4].

At times it was the work of art itself that embodied thanks offered to a holy helper. An intriguing example is a mid-sixth-century silver processional cross from Divirigi, now in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, which bears an inscription in Armenian that has been translated “In gratitude … [missing text] … offers to their intercessor St. George (of) Caginkom” [5]. Although the name of the patron is now lost and the reason for their offering remains unstated, the economic value of this substantial silver object suggests the depth of the unknown donor’s gratitude.

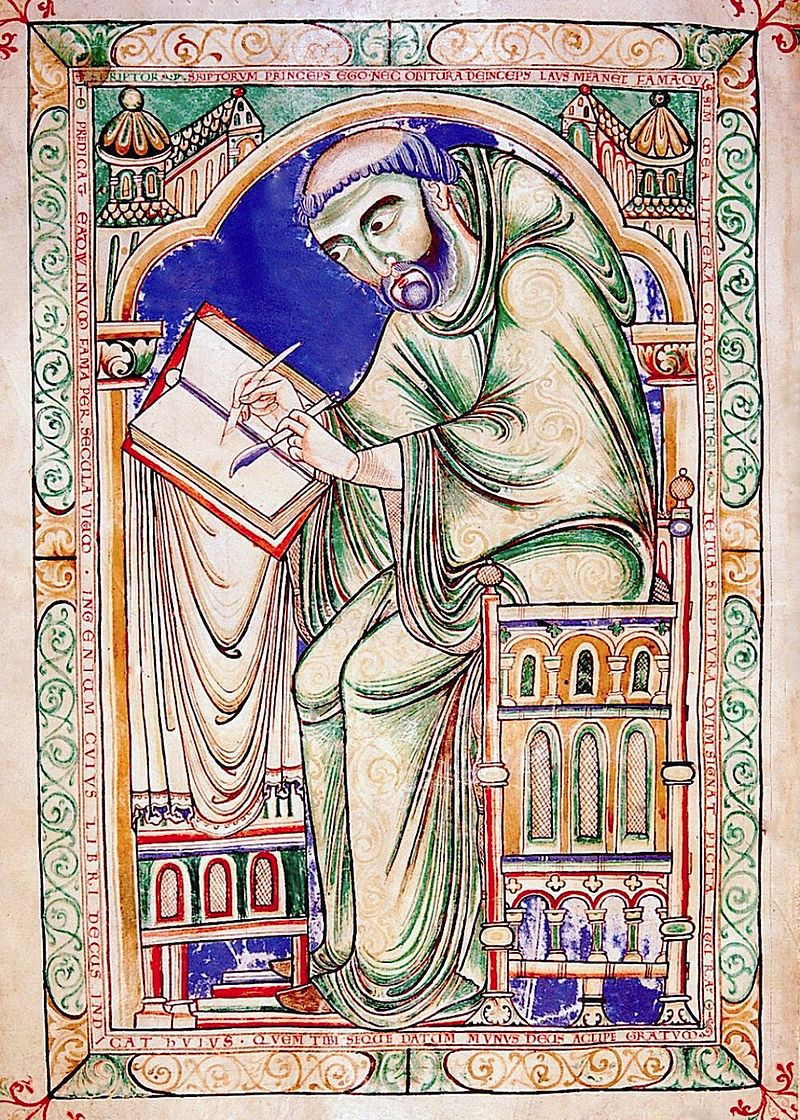

Creators and patrons sometimes added their thanks for the successful completion of a work of art. In an eleventh-century French manuscript of the poetic collection De sobrietate (Leiden, Universiteitsbib. BBL 190, fol. 16v), the poet Milo of Saint-Amand kneels before a church from which the hand of God issues in blessing; an inscription above reads “POETA GRA(TIA)S AGIT DEO PRO EXPLETO OPERE SUO” (The poet thanks God for the completion of his works) [6].

In the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the mihrab added to the structure in the 960s is framed by blue and gold mosaic inscriptions in Arabic that thank God for the successful expansion of the building to accommodate the faithful [7].

The belief that all good things come from God threads strongly through medieval visual culture. Nonetheless, some works record expressions of thanks between mortals—even if often these are legendary. An early sixteenth century tapestry from the Netherlands, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, depicts the story of Perseus and Andromeda in a series of scenes reading right to left [8]. While the climax of the narrative is Perseus’ slaying of the dragon that threatened the princess and her land, the sequence ends with the marriage of Andromeda to Perseus in thanks for his heroic deed, an arrangement for which the young couple appears to be, well, grateful.

The staff of the Index hope that the season finds our readers safe, in good health, and with something to give thanks for.

Like many individuals and institutions, we at the Index of Medieval Art have been saddened and angered by the tragic and unjust deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, and Breonna Taylor in Kentucky, which highlight the persistent patterns of racist violence, harassment, and injustice that mark our nation’s history. As historians, we see the long roots of inequity and prejudice that gave rise to this legacy; as individuals, we commit to eradicating them.

We stand with Princeton University’s president, Christopher Eisgruber, in acknowledging our responsibility to oppose racism and to work to dismantle the systemic structures that allow it to survive. We join him in pursuing the commitment to diversity, inclusivity, and human rights that stands at the core of the university’s mission.

For the Index, this will include continuing to grapple with our own collection’s Eurocentric and colonialist past, as well as our responsibility to present the visual culture of the Middle Ages in a way that is expansive, inclusive, and respectful of the wide diversity of human artistic expression. It also means making it clear that the Index doors are open to all who wish to work and learn with us; inviting and amplifying new voices and perspectives in the work that we do; and creating opportunities that support academic, professional, and individual development for all.

We took modest steps toward these goals in the renaming of the Index in 2017, in updating and beginning to rethink its century-old taxonomy and cataloguing parameters, and through efforts to choose Index conference themes and speakers that are more widely representative of our field’s true diversity. However, we know that there is much more and harder work still to come. We commit to the self-reflection and dialogue that this work entails and look forward to making our values clear in deeds as well as words.

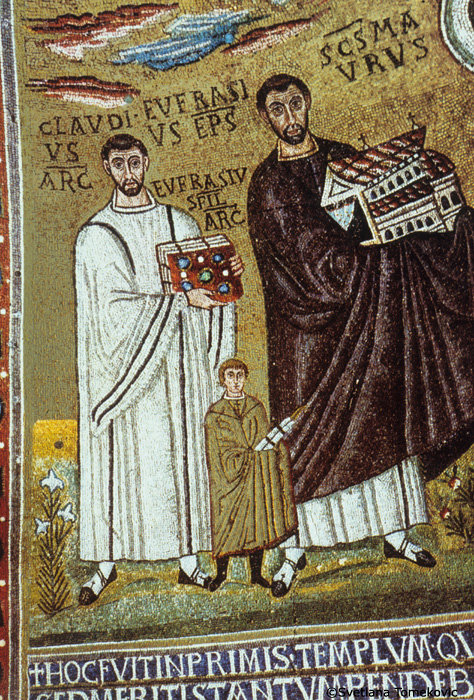

The Svetlana Tomeković Database of Byzantine Art is now live on the Index Digital Collections page. Users can once again browse this rich and extensive archive of photographs of Byzantine monumental art and architecture collected by Dr. Tomeković. There are nearly 4,000 images, many of them from little-studied buildings or sites that are hard to access. Reflecting the interests and specialization of Dr. Tomeković—who published extensively on wall paintings, iconography, and hagiography—the database includes photographs of sites ranging from Eastern Europe to the Mediterranean, including monuments in Greece, Serbia, the Republic of North Macedonia, Kosovo, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia, Italy, Turkey, Georgia, the Republic of Cyprus, and Israel.

The new application created to display this digital image collection allows researchers to browse the entirety of the Svetlana Tomeković Database with thumbnails or to explore the collection by location. Other Digital Image Collections hosted by the Index of Medieval Art are under construction and will be accessible in the coming months. The Svetlana Tomekovic Database of Byzantine Art can be found among the Digital Image Collections listed in the Resources menu on our web site. We hope you’ll explore this collection of images, and let us know what you think!

As always, for copyright and permission queries about images in the Tomeković Database, please contact Catherine Jolivet-Lévy at the Sorbonne in Paris (catjolivet@yahoo.fr).

In response to continued uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, the Index will postpone the “Fragments” conference until November 6, 2021. We are grateful that all the originally scheduled speakers envision being able to join us at that time.

The conference will address the role played by fragments and fragmentation in the medieval and modern understanding of works of art. Speakers will address such topics as the use or reuse of fragments in the creation of new works; quotation and replication as a kind of fragmentation; fragmentation of the perceptual or conceptual experience of a work; deliberate fragmentation or fragmentariness in works such as pilgrims’ tokens or votive objects; and the modern engagement with fragments as an attempt to reconstruct lost works of art, lost visual traditions, or lost cultural practices.

Andrea Achi, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Patricia Blessing, Princeton University

William Diebold, Reed College

Shirin Fozi, University of Pittsburgh

Gregor Kalas, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

Kathryn M. Rudy, University of Saint Andrews

Henry D. Schilb, Princeton University

Susanne Wittekind, Universität zu Köln

In reflecting on the crises precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Index of Medieval Art recognizes that many of our faithful blog readers are facing challenges that were unimaginable even a couple months ago. This has led us to consider how our predecessors must have worked through and responded to the various global catastrophes of the twentieth century. Since the founding of the Index in 1917, these have included the 1918 flu pandemic, two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Cold War, and countless other periods of political turmoil around the world. Through it all, the Index has never existed in isolation, and a sharp-eyed researcher can still find subtle traces of these global calamities in our records.

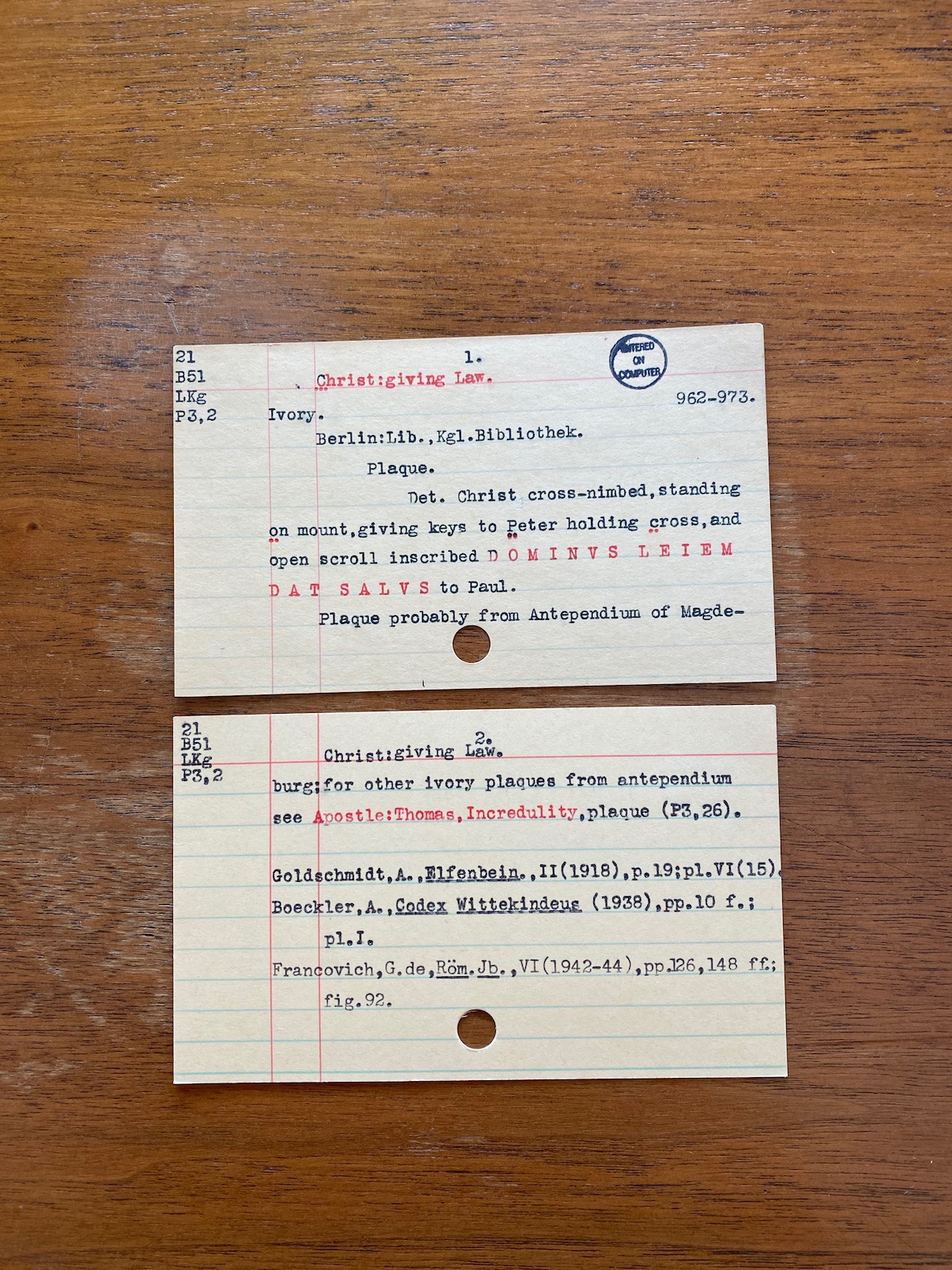

Consider the Index in its original physical (print) form. Visitors who have had the pleasure of thumbing through one of our five card catalogues may have missed a small but intriguing detail.

While the obverse of the main subject cards presented researchers with an iconographic synthesis (at least as it was understood in the twentieth century) in the form of a concise description of a work of art, the reverse sides recorded the creation and revision of the record itself, the handiwork of the scholar-cataloguers who composed all the information on the obverse.

Discreetly located in the corners of individual cards, humble date stamps mark the endpoints of the typically extensive research that went into the composition of all the main cards and secondary cards dedicated to any given monument in the Index. From a practical standpoint, these date stamps were meant to acknowledge any modifications made to individual work of art records, as new publications often generated changes to the identification of particular subjects within the description. Yet they also serve to remind us that Index work continued even during moments of international unrest. The sharp uptick in the number of records originating in the late thirties and forties, for example, not only underscores the exponential growth of the holdings within the physical card catalogue, but also highlights an awareness that many medieval monuments and objects in war zones were in danger of utter destruction.

One such case is a series of date stamps beginning in June of 1933, roughly four months after Hitler was appointed Reichskanzler of Germany, when an anonymous Index staff member added a record to the card catalogue related to one of the sixteen Magdeburg ivories, masterpieces of Ottonian art carved in the tenth century for a subsequently dismantled object—possibly an antependium—in Magdeburg cathedral. The ivory plaque in question bears a representation of the traditio legis, tersely described on the cards as “Christ cross-nimbed, standing on mount, giving keys to Peter holding cross, and open scroll inscribed DOMIVS LEIEM DAT SALVS (sic) to Paul.” The ivory’s location in 1933 was neatly typed above the description as an abbreviation for the Königliche Bibliothek, Berlin’s famed library, today known as the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. It arrived there as one of four other ivory plaques that adorned the book cover of the Codex Wittekindeus, a tenth-century manuscript from Fulda.

A subsequent date stamp confirms that the Index secured a photo of the plaque for the card catalogue on January 9, 1940, a seemingly mundane archival acquisition that might have generated a sense of unease in a research staff painfully cognizant of a Europe that was already in flames. Indeed, the building that housed the Magdeburg ivories and other treasures later sustained an enormous amount of damage from Allied bombing during the course of World War II. When modifications were made to the record in April of 1944, one can imagine that our cataloguer even contemplated whether the ivory plaque still existed at that moment.

That Index staff members were galvanized to participate in the war effort is clear. In 1942, Index director Helen Woodruff herself left the position that she had held since 1933 to join the Women’s Reserve of the United States Navy. Woodruff’s successor William Burke was a member of the Committee on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas, also known as the Dinsmoor Committee, which undertook the creation of maps and lists of monuments for the Allied armed forces in an effort to spare cultural treasures from bombing raids. While the accomplishments of Burke and other members of the “Monuments Men” remain justifiably well documented, it is also worth recognizing that Index staff members also must have felt driven to harness their knowledge of medieval art in the effort to record and preserve Europe’s medieval cultural patrimony. The rapid proliferation of records concerning endangered works of art, while not directly ameliorating human suffering in wartime, clearly acknowledges that the suffering of humanity and the annihilation of monuments were twin evils that both merited the world’s response.

Today we witness the international COVID-19 crisis from within the confines of our homes, electronically connected but physically separated from all the colleagues, students, works of art, museums, libraries, and archives that sustain us intellectually and imbue our own work with a sense of purpose. Although we Indexers have been able to maintain and grow our online database remotely during this difficult period, the physical card catalogue—now an historiographic monument in its own right—remains a testament to all the scholars of the previous century who continued to pursue their research through periods of darkness and uncertainty. Like many of you, we at the Index also look for strength and inspiration in the very manuscripts, monuments, and other precious objects that have by now borne witness to centuries of plagues, wars, and countless other tragedies. Together we must emulate the monuments that we study—and endure.

Catherine A. Fernandez, Art History Specialist

This conference will address the role played by fragments and fragmentation in the medieval and modern understanding of works of art. Speakers will address such topics as the use or reuse of fragments in the creation of new works; quotation and replication as a kind of fragmentation; fragmentation of the perceptual or conceptual experience of a work; deliberate fragmentation or fragmentariness in works such as pilgrims’ tokens or votive objects; and the modern engagement with fragments as an attempt to reconstruct lost works of art, lost visual traditions, or lost cultural practices.

Andrea Achi, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Patricia Blessing, Princeton University

William Diebold, Reed College

Shirin Fozi, University of Pittsburgh

Gregor Kalas, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

Kathryn M. Rudy, University of Saint Andrews

Henry D. Schilb, Princeton University

Susanne Wittekind, Universität zu Köln

Complete conference details, including schedule and a link to free registration, will be shared on this page in late summer.

In recognition of the challenges faced by students, faculty, and researchers now working on line in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Index of Medieval Art at Princeton University has made its online database open-access until June 1, 2020. As always, the database can be accessed at theindex.princeton.edu. Index staff will continue to respond to research inquiries sent via our inquiry form. We hope that this modest change will support researchers both old and new as they navigate teaching, learning, and scholarship during this trying time.

As part of Princeton University’s efforts to reduce the spread of COVID-19, the Index staff will be working remotely for the next several weeks and our reading room will be closed. Our online database will remain accessible, and we will be happy to respond by email or phone to any queries sent in using the research inquiries form. We will post an update when we’re able to return to campus. We thank you for your patience.