In reflecting on the crises precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Index of Medieval Art recognizes that many of our faithful blog readers are facing challenges that were unimaginable even a couple months ago. This has led us to consider how our predecessors must have worked through and responded to the various global catastrophes of the twentieth century. Since the founding of the Index in 1917, these have included the 1918 flu pandemic, two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Cold War, and countless other periods of political turmoil around the world. Through it all, the Index has never existed in isolation, and a sharp-eyed researcher can still find subtle traces of these global calamities in our records.

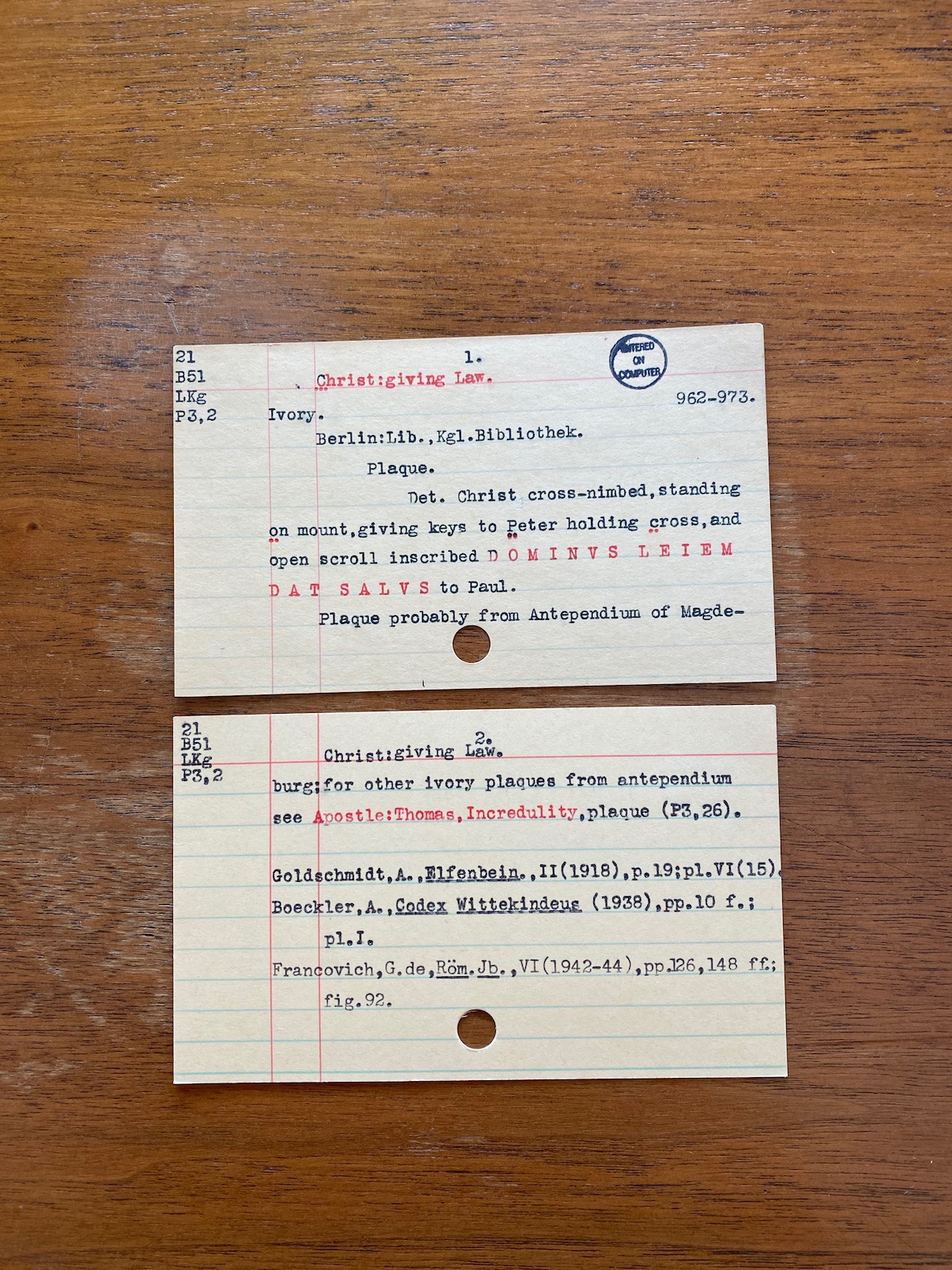

Consider the Index in its original physical (print) form. Visitors who have had the pleasure of thumbing through one of our five card catalogues may have missed a small but intriguing detail.

While the obverse of the main subject cards presented researchers with an iconographic synthesis (at least as it was understood in the twentieth century) in the form of a concise description of a work of art, the reverse sides recorded the creation and revision of the record itself, the handiwork of the scholar-cataloguers who composed all the information on the obverse.

Discreetly located in the corners of individual cards, humble date stamps mark the endpoints of the typically extensive research that went into the composition of all the main cards and secondary cards dedicated to any given monument in the Index. From a practical standpoint, these date stamps were meant to acknowledge any modifications made to individual work of art records, as new publications often generated changes to the identification of particular subjects within the description. Yet they also serve to remind us that Index work continued even during moments of international unrest. The sharp uptick in the number of records originating in the late thirties and forties, for example, not only underscores the exponential growth of the holdings within the physical card catalogue, but also highlights an awareness that many medieval monuments and objects in war zones were in danger of utter destruction.

One such case is a series of date stamps beginning in June of 1933, roughly four months after Hitler was appointed Reichskanzler of Germany, when an anonymous Index staff member added a record to the card catalogue related to one of the sixteen Magdeburg ivories, masterpieces of Ottonian art carved in the tenth century for a subsequently dismantled object—possibly an antependium—in Magdeburg cathedral. The ivory plaque in question bears a representation of the traditio legis, tersely described on the cards as “Christ cross-nimbed, standing on mount, giving keys to Peter holding cross, and open scroll inscribed DOMIVS LEIEM DAT SALVS (sic) to Paul.” The ivory’s location in 1933 was neatly typed above the description as an abbreviation for the Königliche Bibliothek, Berlin’s famed library, today known as the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. It arrived there as one of four other ivory plaques that adorned the book cover of the Codex Wittekindeus, a tenth-century manuscript from Fulda.

A subsequent date stamp confirms that the Index secured a photo of the plaque for the card catalogue on January 9, 1940, a seemingly mundane archival acquisition that might have generated a sense of unease in a research staff painfully cognizant of a Europe that was already in flames. Indeed, the building that housed the Magdeburg ivories and other treasures later sustained an enormous amount of damage from Allied bombing during the course of World War II. When modifications were made to the record in April of 1944, one can imagine that our cataloguer even contemplated whether the ivory plaque still existed at that moment.

That Index staff members were galvanized to participate in the war effort is clear. In 1942, Index director Helen Woodruff herself left the position that she had held since 1933 to join the Women’s Reserve of the United States Navy. Woodruff’s successor William Burke was a member of the Committee on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas, also known as the Dinsmoor Committee, which undertook the creation of maps and lists of monuments for the Allied armed forces in an effort to spare cultural treasures from bombing raids. While the accomplishments of Burke and other members of the “Monuments Men” remain justifiably well documented, it is also worth recognizing that Index staff members also must have felt driven to harness their knowledge of medieval art in the effort to record and preserve Europe’s medieval cultural patrimony. The rapid proliferation of records concerning endangered works of art, while not directly ameliorating human suffering in wartime, clearly acknowledges that the suffering of humanity and the annihilation of monuments were twin evils that both merited the world’s response.

Today we witness the international COVID-19 crisis from within the confines of our homes, electronically connected but physically separated from all the colleagues, students, works of art, museums, libraries, and archives that sustain us intellectually and imbue our own work with a sense of purpose. Although we Indexers have been able to maintain and grow our online database remotely during this difficult period, the physical card catalogue—now an historiographic monument in its own right—remains a testament to all the scholars of the previous century who continued to pursue their research through periods of darkness and uncertainty. Like many of you, we at the Index also look for strength and inspiration in the very manuscripts, monuments, and other precious objects that have by now borne witness to centuries of plagues, wars, and countless other tragedies. Together we must emulate the monuments that we study—and endure.

Catherine A. Fernandez, Art History Specialist