The Index is pleased to serve as site host for “The Medieval Multiple,” a conference organized by Sonja Drimmer (University of Massachusetts Amherst) and Ryan Eisenman (University of Pennsylvania), with support from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the International Center of Medieval Art, the University of Massachusetts Amherst College of Humanities and Fine Arts, Professor James Marrow and Dr. Emily Rose, and the Princeton University Department of Art & Archaeology. The conference will be held both in person and online.

Recent efforts to conceptualize the “pre-modern multiple” only occasionally reckon with the Middle Ages. Medieval multiples are frequently positioned against their modern counterparts—especially print—and subsequently presented as isolated, unrealized forms of mass (re)production. Yet the multiple was not an anomaly but rather the product of a common mode of artistic creation in the Middle Ages, found in a wide variety of materials and object types. Recognizing its ubiquity in visual and material culture, this conference brings together scholars to consider the multiple in the interconnected cultures of Afro-Eurasia between ca. 500 and 1500: its ontological status, the ways in which it could be produced, and how its makers and viewers recognized (or failed to recognize) replication.

For speakers and schedule and to register, please follow this link.

As many of the world’s traditions celebrate the returning light and the promise of new growth, the staff of the Index of Medieval Art wish all our researchers and friends a bright and peaceful winter break.

Our office and reading room will be closed Dec. 26 & 27, 2023, and Jan. 1 & 2, 2024.

By Henry Schilb, Art History Specialist

Is it lost? Was it destroyed? Did it ever really exist at all?

These are questions that we Indexers have to ponder all too often. We try to be both accurate and thorough in our descriptions of the objects in the database, but sometimes we get stumped. Although we Indexers understand that the database we’re building is an invaluable resource—that’s why we do what we do, after all, and we try to do it well—we also understand that there is room for improvement. The Index is neither complete nor perfect. There are gaps and errors in our data, and we know it.

But here’s the thing. In July 2023 the Index of Medieval Art was very pleased to announce that a paid subscription is no longer required for access to the Index database, a change made possible by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the support of the Index’s parent department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University. And now, to celebrate this change, we want to hear from you! Specifically, we want you to tell us what we’ve got wrong. Now that the Index is open to anyone with access to the internet, you can help us correct a mistake, if you find one, or fill in a lacuna in one of our records. It has always been important that we hear from all who use the Index, especially those who know things that we don’t, so what are you waiting for? You can use our Feedback form, or you can also contact one of the Research Staff directly.

Strange as it may seem, one of the most challenging pieces of information to verify is the present whereabouts of an object. As we catalog our oldest records, we sometimes run across works of art that we simply aren’t able to locate. An object’s location is the type of data that can change over time: things get lost; things get sold; things get stolen. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this by giving “Unknown” as the current location. You’ll find hundreds of examples in the Index. When possible we include a “Last Known Location,” the place where an item was last known to exist. A “Last Known Location” can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are lost or in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s current location, that bit of data often eludes us.

So, we’re asking for your help. Here are a few examples:

Can you help us find the piece of gold glass in figure 1? This is the only image we have, an illustration from a nineteenth-century publication. This piece is cataloged as Index system number jkg20200423001, and we have reason to hope that we’ll be able to find this one eventually. You see, a similar piece from the same collection—and illustrated in that same publication—is now in the MFA Boston (MFA accession number 1974.483 and Index system number hds20230131002).

An ivory diptych cataloged as Index system number hds20230620001 presents a similar problem (fig. 2). One wing is now in the Museum Mayer van den Bergh in Antwerp, but the location of the other wing is still unknown. Even the more specialized Gothic Ivories Project at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London lists the location of the left wing as unknown, so it’s not just us. Knowing the location of only one wing of a diptych can be frustrating, but we cling to our hope that we’ll eventually discover the present whereabouts of the other wing.

A more extreme example is cataloged as Index system number hds20230712001, an object formerly in the Rumyantsev Museum, Moscow. All the information we have comes from a nineteenth-century publication [Linas, Charles de, “L’Histoire du Travail a l’Exposition Universelle de 1867,” Revue de l’art chrétien 11 (1867): 344–45]. We have no other leads or clues. We don’t even have a photograph or a drawing to go on! Does it still exist? Is it a phantom? Can you help us find it?

Some of these items may still be in private collections; others may have been destroyed at some point after they were first entered into the Index of Medieval Art card catalog; but others may be sitting in storage in some museum in Oz, or Narnia, or even New Jersey, just waiting for you to point us in their direction. Could that be the case for the little chess piece entered in the database as Index system number hds20230330001 (fig. 3)? Formerly in a private collection in Paris, its current location is unknown to us. Is it in Peoria now? Or Paducah? Or even right here in Princeton? If you know the answers to any of these questions—or if you see other gaps that you might be able to help us fill—please tell us! With your help, piece by piece, we’ll make the Index of Medieval Art as accurate, thorough, and up to date as it possibly can be.

Please save the date for the next Index of Medieval Art conference, “Whose East? Defining, Challenging, and Exploring Eastern Christian Art” on November 11, 2023.

This conference asks how the concept of “the East” has shaped perceptions of Eastern Christianity generally and Eastern Christian Art more specifically, in Euro-American scholarship as well as in the popular view. Building on or dismantling such historical divisions as Western/Eastern Roman Empire, Latin/Orthodox, or simply East/West, speakers will explore what “East” and “East Christian” mean, how the boundaries of these concepts changed over time, and where exactly are the edges of the geographic, political, and religious “East.” This conference will offer a new understanding of the eastern Christian world by examining its cultural production in its own right and demonstrating that its rich, complex, and significant artistic production was not at the periphery of somewhere else, but rather at the center of an interconnected world.

The conference will focus on the regions of medieval Syria, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe. These territories are often neglected in medieval and early modern scholarship as regions that are merely “East” of somewhere more important. The material culture produced in the regions “east” of Western Europe—such as modern-day Ukraine, Serbia or Romania, to mention only a few—has for a long time been considered of “lesser” value or importance compared to France or Italy; the Caucasus is often considered only in relation to Byzantium; and art produced in Armenia, Georgia and Anatolia has often been discussed in terms of a center/periphery dichotomy. Rarely is the visual production of these areas allowed to speak for itself.

Speakers will include:

Anthi Andronikou (University of St Andrews)

Breaking Free from Bias: Eastern Christian Art between the Islamic and Western Worlds

Jelena Bogdanović (Vanderbilt University)

On Theory and Architecture in the Medieval Balkans

Jana Gajdošová (Sam Fogg)

Byzantium and the Court of Emperor Charles IV in Prague

Gohar Grigoryan (University of Fribourg)

The East-West Paradigm in HighMedieval Armenia: The Evidence of Polemical Writings and Visual Sources

Christian Raffensperger (Wittenberg University)

A Third Category: Rus in History and Art

Erik Thunø (Rutgers University)

Nobody’s East: The Interconnected World of South Caucasian Cross Steles

Tolga Uyar (Nevsehir Haci Bektas Veli University)

Thirteenth-Century Monumental Painting in Cappadocia: The Artistic Bonds between Byzantium, Seljuk Rūm, and Eastern Mediterranean World

Margarita Vulgaropoulou (Ruhr-Universität Bochum)

Whose Adriatic? Blurring theBoundaries of East and West in the Artistic Production of the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic

Respondents:

Antony Eastmond (Courtauld Institute of Art)

Mirela Ivanova (University of Sheffield)

The conference will be hosted in person as well as live-streamed. The conference schedule, location details, and live stream registration link will be posted in September.

We are very pleased to announce that as of July 1, 2023, a paid subscription will no longer be required for access to the Index of Medieval Art database. This transition was made possible by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the support of the Index’s parent department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University.

When an online database of Index records was first launched in the 1990s, it was as a subscription service; only those affiliated with a subscribing institution or willing to pay for a subscription of their own could access the full online records. An opportunity to rethink this model arose in 2017, when our shift to a new, non-commercial database platform lowered costs enough that, with careful budget management, the subscription fees could be progressively reduced. In 2023, bridge funding from the Kress Foundation will allow us to eliminate fees entirely, giving researchers at all levels full access to the Index database at no cost, and ensuing support from the Department of Art & Archaeology will allow us to make this transition permanent. We express our deepest thanks to both the Kress Foundation and our department for their support of this initiative.

We look forward to working with the wide range of new researchers who will gain access to our resources, and in the coming months we will offer several online training sessions to introduce the database to those who may be unfamiliar with it. The schedule and signups for these will be publicized on this blog and through the Index social media accounts. Index staff also remain available at all times for researcher questions via our online form at https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/.

We hope that this good new brightens your New Year as much as it does ours, and we look forward eagerly to sharing our resources with students and scholars from high school to retirement, as well as with public learners seeking the reliable information about medieval art and culture that has always been the goal of the Index of Medieval Art.

The Index of Medieval Art will close at noon this Friday, Dec. 23. The reading room will open to visitors on Dec. 28 and 28 and then resume its normal weekly schedule (9 am to 5 pm, Monday through Friday) beginning Jan. 3, 2023. As the days grow longer and winter begins, we share our best wishes for a warm, bright holiday season and promising New Year.

In November 2022 the Index of Medieval Art was pleased to award a Graduate Student Travel Grant to Johann Spillner, a doctoral candidate at the University of London to attend the Index Conference “Looking at Language.” He sends this reflection on his experience:

“It is the sign of a great conference when every paper, no matter how remote to one’s own field of interest, holds your attention. “Looking at Language,” held by the Index at Princeton this November, was certainly a great conference and I count myself lucky to have been able to attend in person due to the generous support of a travel grant from the Index. The papers which addressed, among other things, updates of language in manuscripts (Benjamin C. Tilghman); misspellings in mosaics (Warren T. Woodfin and Ludovico V. Geymonat); or fictional objects in vernacular narratives (Kathryn Starkey) were thought-provoking throughout. The presentation that has stuck with me the most is the one by Prof. Margaret S. Graves on “The Limits of Language,” in which she discussed the art historical bias towards the “talkative” artifact and served as a poignant finale to all the previous papers. Among the things that are still only possible when attending in person (apart from ingesting the excellent food provided by the Index) were the conversations during and after coffee breaks and at luncheon—here, I have to especially thank Prof. Ruba Kana’an for some enlightening and thought-provoking chats.

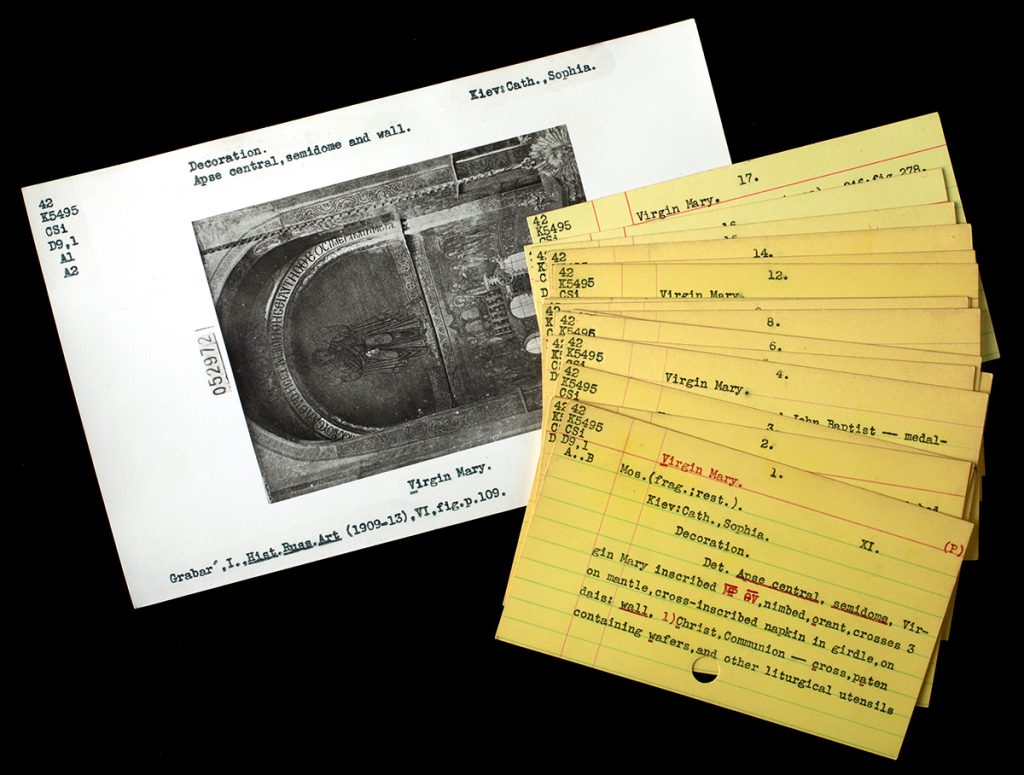

“While the conference alone was well worth my eight-hour transatlantic flight, the second highlight of my trip was certainly visiting the Index itself. Having only seen the online portal of the Index, the actual library and card indices have left a deep impression on me. My own research tries to address the formative power of art historical categorization and language, and standing in the Index itself, I could not help but feel that the Index, through countless years of sweat and, I imagine, a lot of tears, was the physical manifestation of that trajectory. There is something to be said for getting lost in the Index’s system and diving into the countless rabbit holes that the card index offers. While I started by looking at images of Stylites—Christian ascetics who lived out their lives atop of columns and pillars—my interest was caught by a different category of persons positioned next to various building parts: the unnamed nineteenth- and twentieth-century “staffage figures” who give a sense of scale or local color to the photographs of in-situ monuments. These do not represent a category of their own in the Index, but one can imagine the countless stories encapsulated in these photographs.

“All this is to say that my research at the Index was a joyful and stimulating journey. At this point, I would like to thank the Index of Medieval Art, and especially Pamela Patton, Fiona Barrett, and Jessica Savage for the support and their kindness that enabled me to come to Princeton. Special thanks to Jessica Savage for not only sacrificing her time and patience to teach me the ins and outs of the Index system but also accompanying me on my aberrations during my stay.”

And the Index thanks YOU, Johann, for traveling to join us and for sharing your experience with our readers. We hope to see you again soon.

Johann Spillner is a PhD candidate at the University of London, Birkbeck College in the Department of History of Art. His research focuses on Islamic architectural objects in Western museums, more specifically, what their removal, display and representation mean for the subsequent reading of these objects.

The Index of Medieval Art will welcome Princeton University and area researchers to its annual Open House on September 15 from 4:30-6:00 pm. For those farther away: we look forward to hearing about how we can help with your research this year! Please visit our Research Inquiries link with your questions.

Wishing everyone the best for the new academic year!

We are very pleased to announce that Prof. Julia Matveyeva will be joining the Index remotely in August to work on adding iconography from Ukraine’s medieval cultural heritage in the online database. Matveyeva will begin with St. Sophia in Kyiv, a UNESCO world heritage site and central medieval monument in the history of art. Legacy records of the mosaics of St. Sophia in Kyiv already exist in the print collection of the Index, as do those from Saint Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral and almost two dozen records of icons and other objects in Kyiv museums. However, scholars who are not able to travel to use the print Index on the Princeton campus have had no access to these images or their metadata, which moreover are in need of updating. By the end of the project in December, these works of art will be updated and incorporated into the online database, making them available for study by an international community of scholars, students, and lay learners.

Matveyeva is an Associate Professor at the department of Fine Arts and Design of the O. M. Beketov National University of Urban Economy in Kharkiv. Her research has been primarily focused on Byzantine iconography, especially textiles and embroidery, within the Empire and in the neighboring territories, including Kievan Rus’, Romania, Bulgaria, and Italy. Her book Decorative Fabrics in the Mosaics of Ravenna: Semantics and Cultural Context was published in 2020 and she is now working on a new project titled The Evolution of the image of the altar space: from liturgical fabrics to iconostasis in the 4th- 15th centuries. Subjects, semantics, iconography.This project was made possible by a Flash Grant from the Princeton University Humanities Council.

Please save the date for the next Index of Medieval Art conference, “Looking at Language,” on November 12, 2022. Assuming no major changes in university or government pandemic protocols, the conference will be hosted in person as well as live-streamed. It will feature eight medievalist scholars, in a wide range of specializations, who will address the many relationships between language and works of art, including the literal use and/or representation of language in creating a work; the linguistic traditions that surrounded its creation and reception, and the language now used to analyze and understand it. Speakers will include:

Ludovico Geymonat, Louisiana State University

Margaret Graves, Indiana University

Ruba Kana’an, University of Toronto

Sean Leatherbury, University College, Dublin

Sarit Shalev-Eyni , Hebrew University

Kathryn Starkey, Stanford University

Ben Tilghman, Washington College

Warren Woodfin, Queens College CUNY

The conference schedule, location details, and live stream registration link will be posted in September.