If you have feedback or a general inquiry, please use the form below.

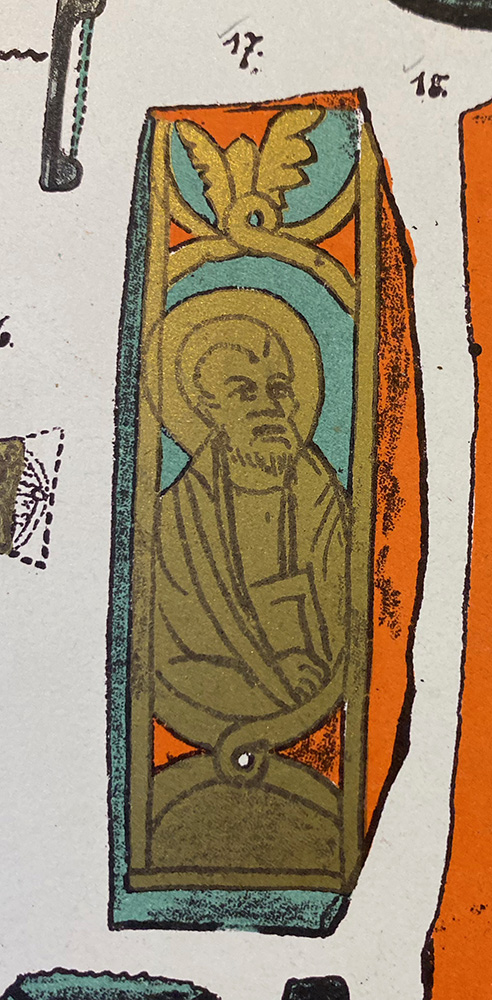

The Index is pleased to announce the launch of a new digital resource for the study of Byzantine iconography, the Lois Drewer Calendar of Saints in Byzantine Manuscripts and Frescoes. Compiled by the late Lois Drewer, PhD, longtime specialist in Byzantine art at the Index, this calendar identifies saints, cites standard and hagiographic references (with a guide to their abbreviations), and concisely describes manuscript illuminations and frescoes. The calendar is organized by feast days in the Constantinopolitan calendar.

There are four main ways to browse the resource. The first is by selecting a month and day under the tab for calendar. This entry point leads to the core of the data, and we recommend this as a good place to start. For example, searching today’s date of the fifth of March reveals three entries for saints: 1. Mark of Egypt; 2. Conon the Gardner; and 3. Hypatius of Gangra. The list you will find there offers identifications, references, and examples.

Many of the saints and holy martyrs included in Dr. Drewer’s calendar are obscure or infrequently represented in medieval art, such as Conon the Gardener (also known as Conon of Perga), a gardener from Nazareth martyred under the Roman emperor Decius (r. 249–251 CE).[1] In some cases, the iconography has not yet been cataloged by the Index, making this an especially useful additional resource.

There are also two lists for iconographic motifs and iconographic scenes with feast days linked on the right, and a list of feasts days organized A to Z. The iconographic motifs and scenes are grouped alphabetically beneath bold headings.

A majority of the headings in this resource cover martyrdom and torture scenes for Byzantine saints–among them holy martyrs, hermits, prophets, and women, but Drewer also included groups for various vestments and clothing, human gestures, attributes, and objects. For example, it is possible to see that an axe is associated with John the Baptist.

In some examples of medieval iconography, the preaching John the Baptist is depicted pointing to an axe at the base of a tree, a reference to Matthew 3:10. Or you can discover that the representation of grief is linked to Sophia of Rome, who is portrayed in various scenes as mournfully throwing out her arms in response to the beheadings of her daughters Pistis, Elpis, and Agape.

There is much to discover by browsing these lists, and we expect that this resource may usefully supplement your searches within the wider Index of Medieval Art Database. You may also try browsing the Svetlana Tomeković Database of Byzantine Art for similar themes represented in Byzantine art. We welcome your feedback, and we look forward to receiving questions through our research inquiries form.

We warmly thank the Index’s Technology Manager Jon Niola for bringing this project to fruition. Lois Drewer dedicated much of her life to iconographic research, and we feel certain that she would have approved of this posthumous tribute. We are proud to offer this additional resource so that all may benefit from Dr. Drewer’s calendar of saints.

[1] Drewer’s database notes three instances of the iconography of the holy martyr Conon the Gardener: a small illustrated Menologion, 1322-1340 (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. f. 1, fol. 30v), and two frescoes in the south aisle of the narthex in Dečani and in the dome of the south tower narthex in Treskavec, all of which have yet to be added to the Index database.

By Henry Schilb, Art History Specialist

Is it lost? Was it destroyed? Did it ever really exist at all?

These are questions that we Indexers have to ponder all too often. We try to be both accurate and thorough in our descriptions of the objects in the database, but sometimes we get stumped. Although we Indexers understand that the database we’re building is an invaluable resource—that’s why we do what we do, after all, and we try to do it well—we also understand that there is room for improvement. The Index is neither complete nor perfect. There are gaps and errors in our data, and we know it.

But here’s the thing. In July 2023 the Index of Medieval Art was very pleased to announce that a paid subscription is no longer required for access to the Index database, a change made possible by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the support of the Index’s parent department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University. And now, to celebrate this change, we want to hear from you! Specifically, we want you to tell us what we’ve got wrong. Now that the Index is open to anyone with access to the internet, you can help us correct a mistake, if you find one, or fill in a lacuna in one of our records. It has always been important that we hear from all who use the Index, especially those who know things that we don’t, so what are you waiting for? You can use our Feedback form, or you can also contact one of the Research Staff directly.

Strange as it may seem, one of the most challenging pieces of information to verify is the present whereabouts of an object. As we catalog our oldest records, we sometimes run across works of art that we simply aren’t able to locate. An object’s location is the type of data that can change over time: things get lost; things get sold; things get stolen. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this by giving “Unknown” as the current location. You’ll find hundreds of examples in the Index. When possible we include a “Last Known Location,” the place where an item was last known to exist. A “Last Known Location” can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are lost or in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s current location, that bit of data often eludes us.

So, we’re asking for your help. Here are a few examples:

Can you help us find the piece of gold glass in figure 1? This is the only image we have, an illustration from a nineteenth-century publication. This piece is cataloged as Index system number jkg20200423001, and we have reason to hope that we’ll be able to find this one eventually. You see, a similar piece from the same collection—and illustrated in that same publication—is now in the MFA Boston (MFA accession number 1974.483 and Index system number hds20230131002).

An ivory diptych cataloged as Index system number hds20230620001 presents a similar problem (fig. 2). One wing is now in the Museum Mayer van den Bergh in Antwerp, but the location of the other wing is still unknown. Even the more specialized Gothic Ivories Project at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London lists the location of the left wing as unknown, so it’s not just us. Knowing the location of only one wing of a diptych can be frustrating, but we cling to our hope that we’ll eventually discover the present whereabouts of the other wing.

A more extreme example is cataloged as Index system number hds20230712001, an object formerly in the Rumyantsev Museum, Moscow. All the information we have comes from a nineteenth-century publication [Linas, Charles de, “L’Histoire du Travail a l’Exposition Universelle de 1867,” Revue de l’art chrétien 11 (1867): 344–45]. We have no other leads or clues. We don’t even have a photograph or a drawing to go on! Does it still exist? Is it a phantom? Can you help us find it?

Some of these items may still be in private collections; others may have been destroyed at some point after they were first entered into the Index of Medieval Art card catalog; but others may be sitting in storage in some museum in Oz, or Narnia, or even New Jersey, just waiting for you to point us in their direction. Could that be the case for the little chess piece entered in the database as Index system number hds20230330001 (fig. 3)? Formerly in a private collection in Paris, its current location is unknown to us. Is it in Peoria now? Or Paducah? Or even right here in Princeton? If you know the answers to any of these questions—or if you see other gaps that you might be able to help us fill—please tell us! With your help, piece by piece, we’ll make the Index of Medieval Art as accurate, thorough, and up to date as it possibly can be.

The Index staff is pleased to announce the relaunch of the Index’s digital image collections, which have recently undergone a massive upgrade. The updated platform hosts ten collections of images generously donated to the Index and made freely accessible to the public through the Index website. These unique documentary resources include more than 50,000 images of medieval art and architecture and reflect the varied interests and travels of their twentieth-century photographers. They represent a range of subjects, techniques, and media, including English medieval embroidery, medieval and Byzantine manuscripts, European choir stall sculpture and stained glass, and Gothic and Romanesque architecture.

Although the images in these collections have not been cataloged with the same level of detail as those in the iconographic database, every effort has been made to assign them basic information regarding location, date, and in many cases, iconographic subjects. The latter can be found in browse lists that include a variety of iconographic topics, including saints and martyrs, animals, zodiac, occupations, and secular and religious scenes, all updated to follow the current subject standards of the main Index database. Browsing these subject lists reveals much about each collection. For instance, the subject list for the “Opus Anglicanum” database—an image collection of medieval English needlework on ecclesiastical and secular textiles—includes numerous saints especially venerated in England, with multiple scenes for Margaret of Antioch, Nicholas of Myra, and Thomas Becket.

Browsing the subject list of another collection, the Elaine C. Block database of misericords, reveals the wide variety of drôleries that decorated the wooden under-seat structures: fantastic creatures, battling animals, and figures playing in sports and games, engaged in occupations, or enacting proverbial lessons. John Plummer’s database of medieval manuscripts includes large numbers of biblical and apocalyptic images, including scenes with Christ, David, and the Virgin Mary, and other popular saints found in late medieval prayer books. The subjects in Plummer’s collection closely resemble those found in Jane Hayward’s collection, perhaps reflecting the shared interests of two scholars were curators at major collections in New York City during the second half of the twentieth century.

The Gabriel Millet collection comprises the study and teaching images of that scholar, an important archaeologist and historian of the early twentieth century who specialized in Byzantine art. Subjects represented here include multiple biblical figures and scenes, but also Byzantine generals and emperors and several text subjects, such as the Chronicle of Manasses and the biblical psalms by number.

The Gertrude and Robert Metcalf Collection of Stained Glass is a documentary treasure for the study of Gothic stained glass. The Metcalfs, who were both stained glass artists and experienced photographers, took more than 11,000 images of stained glass from European monuments, covering sites in Austria, England, France, Germany, and Switzerland. Their images of stained glass windows are a fascinating record of a fragile artistic medium, captured during fragile times. Their travels coincided with the dawn of World War II in Europe over the years 1937 and 1939, and they produced a body of documentary evidence that became critical to postwar restoration efforts. A look at the Metcalf subject list reveals many of the expected themes in medieval iconography, but also significant iconographic cycles for several French bishops, such as Austremonius and Bonitus of Clermont, Germanus of Auxerre, and Martialis of Limoges.

Geographically, the collections cover country and city locations in four continents—Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America—from obscure sites to famous ones, and they include many types of repositories, from in-situ locations to museums, libraries, and private collections. To better accommodate browsing by region, locations in all the collections have been formatted to begin with the country. Each collection is introduced with general information about its history, scope, and image use policies. It has been satisfying to edit and release these collections—now with more consistent information and a more secure digital platform—knowing that they are now more useful to scholars. Your feedback on the collections is welcome via this form.

The Index of Medieval Art has completed a systemwide update aimed at making the database both more user-friendly and fully compliant with current accessibility standards. Launched April 1, the update includes the following improvements:

We encourage researchers to explore the updated site, making use of the new Help pages linked on the Welcome page. As always, we welcome your research inquiries and feedback.

Third in a series of short blog posts introducing new features of our online database

Have you tried out our Medium filter yet? As part of our ongoing series introducing specific features of our database to assist you in developing research strategies, let us direct your attention to the Medium field. First, you may ask, what exactly do we mean by “Medium”? In the Index database, “Medium” refers both to the materials that compose the work of art and to the methods of facture or technique employed in its creation. As Herbert Kessler rightly observes, “matter mattered in the Middle Ages,” and we at the Index wish to foster exciting new scholarship related to the iconography of materials.[1] A cursory glance at our Medium category under the “Browse” tab reveals an extraordinary array of materials and techniques. Objects may include materials ranging from “acacia” wood to “zeiler sandstone,” and all these materials might have been “hammered” and “punched,” or “chiseled” and “incised,” or subjected to many other possible means of manipulation.

But what if you are not ready for this level of specificity? For more general Medium searches, we have devised a series of basic category terms to help you find what you need: “stone,” “gems,” “wood,” “ivory,” “metal,” “enamel,” and “textile.” For example, let’s say you’re interested in representations of the Virgin Mary in any kind of stone. A keyword search for “Virgin Mary” on the database homepage will yield thousands of results in all media. So, if you want to limit your results to images in stone, simply find the “Filters” tab under “Advanced Search” and select “stone” under the Medium filter. Click on “Search,” and you will reduce your list to 1,752 records.

Now what if you know that you’re searching for representations of the Virgin Mary in a specific kind of stone? This time, let’s say you’re looking for marble sculpture. Instead of sifting through all 1,752 records for marble examples, just try selecting “marble” in the Medium filter. This should bring your results down to a mere 410 records.

You can also try refining your search with another filter. Interested in marble representations of the Virgin produced in medieval France? Add “France” in the Location filter, and you’ll narrow your results to 55 records.

So, whether you’re searching within broad categories or examining specific materials and techniques, try using the database’s Medium filter to adjust your search to your research interests.

Here are a few additional pointers:

So, as you undertake your research with us, we hope that you’ll give the Medium filter a try. As always, please feel free to send us questions or comments about any aspect of the IMA database. Contact us at theindex@princeton.edu. Matter matters…and so does your feedback!

[1] Herbert Kessler, Seeing Medieval Art (Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2004), 14.

First in a series of short blog posts introducing the new features of our online database

Did you know that you can search The Index of Medieval Art for information about patrons of medieval art? The Index records both identified and unidentified patrons, the latter entered as grouping terms for types of patrons (Male, Female, Couple) and major monastic orders, such as Augustinian, Benedictine, and Carmelite. There are also general headings for anonymous male and female patrons (Male, unidentified and Female, unidentified). Names of churches, monasteries, and abbeys are given by their proper titles, such as Canterbury Cathedral, but might be further identified by location (e.g. Abbaye d’Anchin [Pecquencourt, France]).

For an overview of our patron headings, click on Browse at the top of the Index landing page. This will bring you to a list of over 900 names and grouping terms sorted in alphabetical order. To reach a specific entry, type the first few letters of a name into the search line at the top of the list. For instance, typing in “Blanche” will bring you to all Blanches from Burgundy, Castile, France, Navarre, and also the late 14th-century Countess of Geneva. Clicking on any patron heading will return a glossary entry comprising a biographical note with dates, alternate names of the patron, a bibliographic citation, an external reference for the authority source, and all the work of art examples linked to that patron.

Our patron entries are formatted in keeping with standard biographical authorities, such as the Library of Congress Name Authority File, the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), and Oxford References. Patrons are identified in the Index database by their roles and dates when these are known. When performing an Advanced Search in the “Terms” screen, you may prefer to keep the Match Type set to “Default,” which will search all parts of the heading. In the “Terms” window, a search can be formulated with keywords such as “Pope,” “Doge,” or “Prince,” using “Patron” in Search Fields to locate medieval patrons by their role. Similar keywords, along with keywords for place indicators like “Monastery” or “Convent,” can be searched against the “Patron Note” field, which will search the biographical notes in the patron glossary.

Many of the monastic patrons contain their locations in parentheses after the name of the community, so countries of patronage activity can also be searched as keywords. For instance, searching against “Patron” or “Patron Notes” with the keyword “Italy” returns over 150 records. This indicates artwork results for a patron who was active in Italy. From here, in the “Filters” window, the Date Slider can be used to refine results. The “Terms” search can be refined with any of the additional filters, including “Location,” “Medium,” “Style/ Culture,” and “Work of Art Type.”

Are you interested in finding out which female patrons were active in France in the 14th century?

In the Advanced Search “Terms” screen, enter the keyword “Female” and choose the Search Field “Patron” (keeping Match Type set to “Default,” as recommended).

Then, go to “Filters,” select “France” as a Location, and set the Date Slider to 1300 and 1399. This search should yield 27 examples, where a female patron is connected to the 14th century work made in any part of France.

*In results, please note that work of art records will include Main records indicated with a logo picture.

As you search for patrons in the new Index of Medieval Art database, bear in mind that visual representations of patrons are found in the Subject field. To find images of patrons, you can browse or search the Subject field with the keyword “Donor.” To read more about medieval patronage practices in general, you might find the Index’s 2013 conference publication Patronage, Power, and Agency in Medieval Art of interest. Enjoy refining your searches and browsing the range of patrons we record in the Index! And please remember that we are always happy to have your feedback. Get in touch with us at theindex@princeton.edu.

Isidore of Seville (?) at his desk, from the Stuttgart Psalter (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, MS 23), fol. 1v

As our subscribers will have heard, refinements of the new Index database application are proceeding on schedule, and on March 30 it will become the primary and only route to online search of Index records. We think you’ll find the new platform much more user friendly and appreciate features such as filtered searching, a date slider, and (mirabile dictu) immediately visible thumbnail images.

Subscribing institutions should be switching the URL to https://theindex.princeton.edu, and some may have done so already. You should also be able to access the database by navigating to this URL if you are on site and using the IP range of a subscribing institution.

If you’d like a jump start in using the new system, please check out the tips below. Your feedback is welcome at theindex@princeton.edu.

Follow this link to reach the landing page:

https://theindex.princeton.edu/

Once there, click on the “Search” dropdown and choose “Advanced Search.” Type one or more keywords into the “Search Expression” line for a Boolean search, which can be filtered by Work of Art Type, Creator, Location, etc. in the fields below; dates can be refined using the slider. Exact-phrase searching iis coming in the next few weeks, so if it isn’t active when you visit, please check back.

Clicking the search button calls up a results list that appears below the search filters; click thumbnails to see the full records. Works can also be searched for by browsing the Index authorities for Subject, Creator, Patron, among others; each authority includes an expandable bar containing to the records in which the term appears.

As you try out the site, please remember that some design elements and search tools are still actively in development: layout, terminology, and search dynamics still may change. This makes your feedback all the more useful, as it helps us to evaluate future refinements. We look forward to hearing from you!

As our regular readers know, the Index of Medieval Art recently launched a redesigned database. A challenging part of preparing for this event (codenamed Project Phoenix) was revisiting, reevaluating, and often revising how the Index has traditionally presented certain types of information. A century of accumulated data can reveal some unexpected things. Since the Index was founded in 1917, the history of the world has been…oh, let’s just call it “eventful.” Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the process of updating our outdated records as we upgrade the Index database has been a sobering reminder of all that has changed in the world, all that we have learned and achieved, and all that we have lost over the last one hundred years.

One set of data that made the need to revise our records very clear to us was the place names that we use. Obviously, names change, but we can point to a variety of reasons for the outdated information in the Index database. Some names in English are translations from the language of the place in question. In English usage, Wien remains Vienna, and Firenze remains Florence, but Lyon has superseded Lyons. Sometimes it’s a question of both language and script. What rules of translation and transliteration should we prefer? Depending on who is speaking or writing, a single place can be known by many names. For example, the Armenian place name Հռոմկլա can be transliterated as Hromkla, Hṛomkla, Hṛomklay, or Hrongla, but it can also be Rum Kalesi, Rūm ḳal‘esi, Rumkale, Qal‘ah Rumita, Qal‘at al-Rum, Qal‘at al-Muslimin, or Kela zêrîn. Can a single rule be applied consistently and make sense to users of the Index?

No matter the topic under discussion among the research staff at the Index, the answer to that last question turns out to be “no” frustratingly often. Language, like the rest of the world, is just too messy. One of our solutions, at least regarding how we handle locations, has been to embrace the messiness so that we simply have to account for complexity. So, when choosing an authority to cite for place names (authorities such as the Getty Thesaurus of Geographical Names and the Library of Congress, among others), we quickly decided that we need not cite the same authority in every case.

In addition to the problem of language, there are also outright changes of name that we have to recognize. The city of Byzantium has gone by a few different names in its history (Fig. 1). It’s called Istanbul now, but Istanbul was Constantinople. Now it’s Istanbul, not Constantinople. Believe it or not, that change became official many years after the Index was founded. It’s also worth mentioning that, although the name of that city should really be spelled “İstanbul” in Modern Turkish (with a dotted capital “İ”), the Index will continue to use the spelling familiar to English readers. Thus, even for something in situ, the database might list different names for an object’s or monument’s location of origin and its current location. Hagia Sophia is in Istanbul, but it was in Constantinople. (Have we given you an earworm yet?) Nevertheless, as we update the Index database, we will cross-reference place names so that, for example, a search for Istanbul (or İstanbul) will always also lead you to Constantinople.

But it’s not only names that change. Borders also sometimes shift. Once upon a time, when the Index was new, the city of Königsberg was in Prussia. After World War I, Königsberg was part of Germany (the Weimar Republic, that is, and then Nazi Germany), and by the end of World War II, much of the city had been destroyed, including museums and medieval monuments. That makes Germany the last known location for those buildings and the objects they contained (Fig. 2). Once the Prussian home of Immanuel Kant, Königsberg is now within the Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland. And, oh yes, it’s called Kaliningrad now. Our goal at the Index of Medieval Art is to continue to update our database to account for such changes.

By the way, for those of you as interested in topology as you are in topography, Kaliningrad was—when it was Königsberg—the subject of a famous logic puzzle. The city straddles the Pregel River, and there are two islands in the river, a feature reminiscent of Paris. The islands in Königsberg were connected to the rest of the city, but the bridges were configured in such a way as to give rise to this puzzle: “Can you walk through Königsberg crossing each of the seven bridges only once?” This puzzle has rules, of course: you have to cross each bridge only once, and you must cross each bridge completely (without turning around in the middle), but you may not cheat with a boat or hot air balloon. The puzzle was solved in the 18th century by Leonhard Euler, the great Swiss mathematician and general smarty-pants. When it comes to walking through Königsberg, crossing each of the seven bridges only once, Euler proved that…spoiler alert…it couldn’t be done!

Time does things to maps. Not only do place names change and frontiers shift, but cities rise and fall, roads are rerouted or renamed, and buildings are razed or rebuilt. Sometimes new bridges replace old ones, so that even that famous logic puzzle about the seven bridges of Königsberg has been affected by the last two centuries of human history. Only two of the bridges that Euler knew still exist, and the new configuration of bridges means that the Königsberg puzzle is no longer a puzzle at all in Kaliningrad!

On a related note, have you ever wondered, “When is a map not a map?”

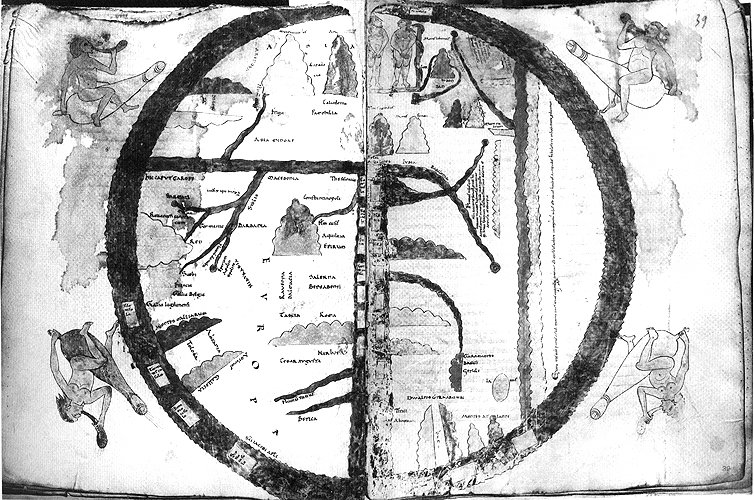

More precisely, the question that arose recently at the Index was this: “When is a map a map, and when is it a representation of a map?” Questions like this one can lead to surprisingly lively discussions at the Index of Medieval Art. This particular question came up while we were discussing how the Index ought to categorize certain subjects. It seems clear that some things are maps, like the Hereford Mappa Mundi. It also seems clear that some images include representations of maps, without actually being maps (Fig. 3).

However, some cases may be less clear, like a map in the Turin Beatus (Fig. 4). Is this an illumination that consists of a map, or is it a representation of a map? In other words, when is an object a map, and when is “map” the subject of an image?

What we at the Index sincerely hope is that you, everyone who uses the Index, will join us in addressing such questions. We invite subscribers to try out the Project Phoenix beta to see what we’ve been working on. We welcome your thoughts, so please tell us about your experience using the database, or share your observations about how we handle the content. Please bear in mind that this is the beta stage of development, so not everything is working perfectly yet. Some features have not been fully implemented, and some may be disabled from time to time while we work to improve them. It will also take us some time to edit the contents of the database so that everything is handled consistently within our revised format. In the meantime, the old, familiar database is still available to subscribers, and it will continue to be available until we are confident that the new version can supersede the old one.

We look forward to hearing from you. Your insights and feedback will continue to be vital to the success of this enterprise, just as they have been through the first 100 years of the Index of Medieval Art.

Henry Schilb

The Index of Medieval Art is proud to announce that the new database platform is now in beta. Project Phoenix is the culmination of years of planning and development in collaboration with Luminosity Labs. When we first conceived this project in the summer of 2014, we decided that we needed to develop a platform that was modular enough to build upon in the future. It was important to us that, as methods of study change, the tools we provide researchers must be able to evolve as well.

There are now more access points into our data. Our new advanced search and refinement tools will give our users much greater flexibility, so that results can be narrowed to isolate specific works of art. Users will now have the ability to target their queries with multiple factors—such as date, location, subject, media, and more—but with precise control.

The new platform also introduces a responsive design, meaning that the user interface can adapt to your device whether it is a large computer monitor or a smaller tablet. We estimate as much as 50% of our web traffic is from mobile devices such as iPads, so we are working to make sure that we can support the mobile experience.

This is just the start: we will be rolling out many additional features over the next few weeks and months. In the coming year we plan to introduce a new interface for navigating in situ works, as well as a new interface for exploring our subjects by hierarchical classification rather than keywords alone.

In 2018, we will also be implementing IIIF support for images. This will mean that works of art for which we have high-resolution images can be examined in greater detail. You will have the ability to zoom in and out, and to pan around the images, all from within our web application.

We invite you to try out our Project Phoenix beta to see what we’ve been working on. And please send us your feedback! We welcome your thoughts, but keep in mind that this is the beta stage of development, so not everything is working perfectly yet. Some features have not been fully implemented, and some may be disabled from time to time while we work to improve them.

In the meantime, the old, familiar database is still available to subscribers. This legacy database will continue to be available until we are comfortable that the new version can supersede the old one completely.

Thanks for your support and patience through these exciting times. We look forward to hearing from you about the new design!