The Index of Medieval Art invites applications for a four-month, remote, part-time research position to assist in incorporating key mosaics and paintings of medieval Kyiv into the Index database. This position is made possible by a 2022 Flash Grant from the Princeton University Humanities Council and consists of a $5,000 honorarium to be directed to the scholar.

The successful applicant should have relevant training in art history, preferably with a medievalist background, and should hold a doctorate or have completed all but the dissertation. Applicants may be of any nationality, but preference will be given to a scholar whose work has been disrupted by the crisis in Ukraine. A reading knowledge of Russian and Ukrainian is preferable.

The work position will require roughly two days a week of remote work over a four-month period, beginning in summer of 2022. The successful applicant will work with the Index research staff to catalogue Ukrainian monuments, beginning with the cathedral of St. Sophia in Kyiv. They will be trained in Index norms in cataloging the monumental structure, describing the iconography of its paintings and mosaics, transcribing inscriptions, and adding bibliographic citations, Index subjects, and other metadata. Staff guidance and scans of the relevant print material will be provided. The timeline for this work is somewhat flexible but must be completed by the end of the funded period, December 31, 2022.

To apply, please send a CV and letter of interest to marossi@princeton.edu and ppatton@princeton.edu by June 1, 2022

NB: This satirical post was shared in celebration of April Fool’s Day 2022.

Many here in New Jersey are admirers of Nora, the Piano Playing Cat, the Camden kitty who since 2007 has wowed music lovers worldwide with her talent at the keyboard. Her fame even inspired the Lithuanian conductor Mindaugas M. Piečaitis to compose her a “Catcerto.” If you haven’t ever heard this piece, by the way, it’s well worth a listen.

But are musical moggies really a modern phenomenon? Evidence unearthed by researchers at Princeton University’s Index of Medieval Art suggests otherwise. Manuscript illuminations from late medieval Europe clearly depict cats performing on a variety of musical instruments, from the organ and tabor to the vielle and more. Here we present a preview of findings from this pathbreaking research project, soon to appear as an article in the interdisciplinary medieval studies journal Scientia de animalibus.

Musical training of felines often began at the keyboard, allowing teachers to capitalize on cats’ natural impulse to bat at a target with their paws. Meticulous application of a featherstick to each key to be struck, along with the copious provision of treats, encouraged both musical precision and a vigorous technique on both portative and positive organs.

Further mastery of percussion came with training in the tabor, a small hand- (or paw-) held drum that is played with a stick. A small strap was used to affix the drum to the cat’s left paw while it impaled the stick with its claws. Although this technique must have been difficult to learn, the surviving images suggest that some cats mastered it so well that they could stand on their hind legs while playing.

Those cats with sufficient coordination and ambition could next be moved on to bowed instruments like the vielle, shown here. In addition to requiring vertical balance, this instrument demanded both toe dexterity and a highly refined ear, the latter fortunately not a problem for these aurally acute ailurids.

Only those cats with the highest musical ability could advance to learning the bagpipes because of the precision needed to coordinate breathing, elbow pressure, and the placement of toe pads. Among the few feline masters of this instrument was a white monastic cat named Pangur Bán, whose signature “Katzenellenbogen” performance technique is still used by pipers today. Pangur was a true polymath who was also commemorated in verse for his “joyous with speedy going” after mice in his home abbey near Reichenau. Index researchers believe that the image above may portray Pangur himself, based on his obvious mastery of tongue and paw position.

We at the Index hope that you’ve enjoyed this foray into our research on medieval feline musicians, who set the stage for Nora and the rest of today’s musical cat performers while also launching your April Fool’s Day 2022 on a truly harmonious note.

As many Index subscribers know, reducing subscription fees for the Index of Medieval Art database has been an institutional priority since the launch of its new digital platform in 2017. Because the Index budget, which supports the work of seven full-time staff members as well as a program of respected publications and conferences, relies in part on subscription revenue, such reductions have had to be gradual. But they have continued, and as we approach the five-year mark, we’re very pleased to announce that our institutional subscription fee for the coming fiscal year will be $500 per year, one third of the $1500 per annum paid by institutions when the reductions began.

We recognize that access to online resources has become increasingly important as a global pandemic and ongoing budget pressures continue to reshape teaching, learning, and research in higher education. We hope that this further fee reduction will help more institutions choose to make the Index available to their scholarly communities. Should you wish to discuss a free trial or subscription to the Index, please contact office coordinator Fiona Barrett (fionab@princeton.edu).

On January 13-15, the Index will co-host the hybrid conference “Power, Patronage, and Production: Book Arts from Central Europe (ca. 800-1500) in American Collections” in conjunction with the exhibition “Imperial Splendor: The Art of the Book in the Holy Roman Empire, 800-1500” at the Morgan Library & Museum. The exhibition presents material that has never before been gathered together, treating topics including visual rhetorics of power in book media, the production and patronage of manuscripts, the relationship between vernacular and Classical languages, and the position of imperial cities in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The conference expands this with papers on such themes as the networked relationships among centers of production; the representation of male and female patrons; early print culture; and the role of books in key developments for liturgy, private devotion, chronicle writing, and the law. A schedule of speakers (including Index Specialist Jessica Savage) is available here.

The conference will run in hybrid form. In-person attendance is contingent on space; due to current campus public health policy, registration will be limited to Princeton University ID holders and visitors sponsored by the Department of Art & Archaeology. We cordially invite attendance on Zoom by all interested in the conference proceedings.

The conference is co-sponsored with the Department of Art & Archaeology, the Center for Culture, Society and Religion, the Program in Medieval Studies, the German Department, Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS), Humanities Council, Delaware Valley Medieval Association and The Morgan Library and Museum. We hope many of you can join us for this event.

You know them by heart. You can hear them coming. Four notes, with six geese a-leading the way. Only four notes, but you can’t wait to belt them out. And then it happens:

“Five go-old rings!”

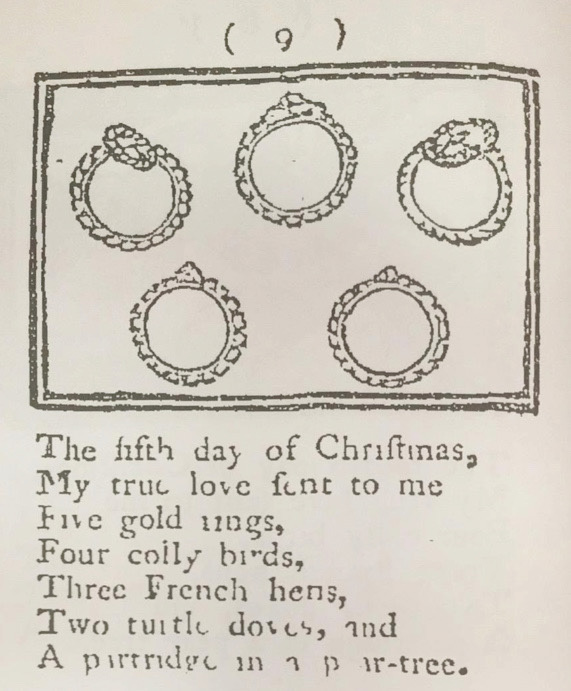

Those gold rings you love to sing about have been around since at least the eighteenth century, when the lyrics to “The Twelve Days of Christmas sung at King Pepin’s Ball” were printed in a little book called Mirth without Mischief (Fig. 1). [1]

No music was printed with the lyrics in Mirth without Mischief, but the words are roughly the same as you remember them, possibly representing the oldest printed evidence of the carol. The earliest known version of many different versions to come, it differs from the carol as we usually hear it today only in the order of the gifts from the ninth through the twelfth days. Partridge? Check. And two turtle doves, three French hens, and so on up to the usual seven swans a-swimming and eight maids a-milking, but then there follow nine drummers drumming instead of nine ladies dancing, ten pipers piping instead of ten lords a-leaping, eleven dancing ladies (probably preferable to the usual eleven pipers piping), and no fewer than twelve lords a-leaping instead of twelve drummers drumming. That’s just a lot of leaping lords, I must say! You’ll also notice that the birds on the fourth day were called “colly birds” back then, not “calling birds.” “Colly” just meant black like coal, so what we have is a flock of blackbirds. But all five gold rings were there already. Wait…is it “gold rings” or “golden rings”? I’ve heard it both ways, sometimes simultaneously. When exactly did “five gooooo-ooooold rings” become “five golll-dennn rings”? The version in Mirth without Mischief is clear about my true love’s having given me “gold” rings, not “golden” rings. It really doesn’t matter, I suppose, but the word “golden” does seem to devalue the gift. I mean, if the rings are only “golden” and not actual gold, then why do I want forty of them? Perhaps it’s just that even two notes per syllable is too much melisma for some carolers, so they need the extra syllable to sing.

Maybe I ought to get to the point. Typically, in this space, someone from the Index of Medieval Art will explore a topic relating to iconography, some theme or scene rendered in one or more media, perhaps a subject relevant to the season. This time, however, I want to look at a category of object. Yes, I’m going to show you five gold rings, each one cataloged in the Index of Medieval Art database. Of course, if you’ve ever done the math, you’ll be aware that my true love intends to send me not just five gold rings but a total of forty by the time Epiphany rolls around on the sixth of January. I always imagine the narrator of the carol wearing them all at once, or as many as possible, like Liberace or Ringo Starr. Presumably, when Ringo sings this carol, Barbara Bach is the “true love” in question. I wonder, has she ever given Ringo five gold rings, or would that be a bit “coals to Newcastle”? Er, Liverpool?

Really, we should be grateful that the familiar version of the carol includes inanimate objects on the fifth day. According to one reported version of the lyrics, instead of gold rings, you could have had “five hares running” to deal with (forty total, and…well, they’re hares, so, you know). [2] In that version, your true love also gives you four ducks quacking on the fourth day. But that version isn’t really a song. It’s a game of forfeits—in which each player takes a turn reciting the whole list and adding to it—a game that seems to be the origin of the structure of the lyrics of the carol.[3] And there’s another theory regarding how the fifth day wasn’t always about jewelry. It’s possible that our gold rings are a corruption of “goldspinks,” a Scottish word for goldfinches.[4] I suppose that would make more sense, given all the other birds my true love is sending me.

But I still prefer the familiar version of the carol that emerged in 1909, when Frederic Austin published his arrangement.[5] And the “five gold rings” part that’s so fun to belt out? It was Austin who composed those two famous bars and added them to his arrangement of the traditional melody, which was copyrighted by the publisher![6] It was also Austin who added the word “On” to the beginning of each verse. Interestingly, for the twelfth day, Austin doubled down on the melisma, so the final verse calls for the word “gold” to be sung with a flourish of four notes rather than the two usually sung today.[7]

OK, but what about those five gold rings I promised to show you? Whenever I hear “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” the rings I picture in my head are simple bands of gold, like the one Bilbo stole from Gollum in those Peter Jackson movies. But a gold ring can also be delicate openwork like this example at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Fig. 2, Index of Medieval Art system number 144086).[8]

On this early Byzantine ring, we find two birds (shall we imagine that they’re turtle doves?) flanking a vase among a scrolling grapevine. The crafting of this ring combined several methods. The birds, vase, and leaves appear to have been cut from a sheet of gold. The vine is filigree, delicate work created with gold wire.[9] The bunches of grapes were created by granulation, a technique in which tiny spheres of metal are fused together.[10]

As intricate as the openwork may be, this ring is still only a circle, a hoop without a bezel. The bezel is the “top” part of the ring that’s displayed on the back of the hand. A bezel can be flat, raised, incised, or filled with a gem.[11] There is even such a thing as a reversible bezel. The ring in figures 3a and 3b (Index of Medieval Art System number 60117), possibly from Syria and now at the Benaki Museum in Athens, has a swivel bezel with an image of Thekla of Iconium flanked by crosses and animals (probably lions) on the obverse (Fig. 3a).[12] On the reverse is an archangel holding a cross-staff and a globe (probably, though it’s hard to make out) (Fig. 3b).

If you were to inspect the edge of the bezel, you would find a Greek letter inscribed on each of the six sides not connected to the hoop. The characters ͵ϚΡΛ on three sides of the bezel are numerals, possibly giving the year 6130 of the Alexandrian Era (638/9 CE), or possibly having an apotropaic significance, while the other three letters—ΧΜΓ—are probably an abbreviation of Χριστὸν Μαρία γεννᾷ (Mary gives birth to Christ) or possibly something like Χριστός Μιχαήλ Γαβριήλ (Christ, Michael, Gabriel).[13]

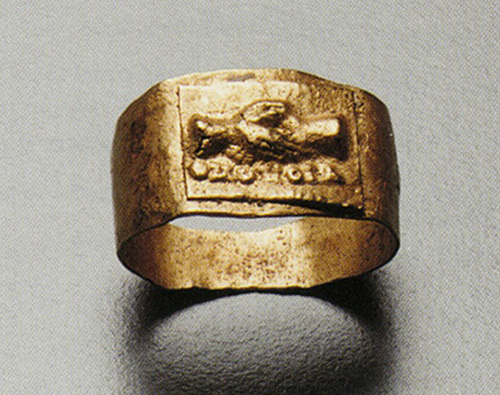

Although the space on any ring is limited, not every inscription on every ring is a cipher. For example, in the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University Bloomington, there is a Roman marriage-ring with a very straightforward message (Fig. 4, Index of Medieval Art system number 143736).[14] Below clasped hands in relief are the raised letters of the Greek word ΟΜΟΝΟΙΑ (ὁμόνοια, meaning concord, harmony, or like-mindedness).

The image and inscription were possibly created with a stamp or by working a small sheet of gold into a die.[15] The tiny relief was then applied to the gold band. The image is simple, and the significance of the word ὁμόνοια is quite clear.

The same word appears on the bezel of a somewhat later marriage-ring from the Eastern Mediterranean and now at the British Museum (Fig. 5a, Index of Medieval Art system number 62961).[16] The inscription and all the images on this ring, on both the hoop and the bezel, are rendered in niello, a metalwork technique in which a black alloy is used to highlight an engraved or incised image.[17] On the bezel we find the inscription OMONV/A (ὁμόνυα, a variant spelling of ὁμόνοια), but instead of clasped hands above the inscription, we see the Virgin Mary and Christ crowning the couple getting married, so the ring bears a representation of the person who wore it! Above this scene is a star. Yes, there’s a star…on a gold ring…so that makes it a gold ring star. Get it? You see, it’s funny because “gold ring star” sounds sort of like “Ringo Starr,” but inside out…. No? Never mind.

There are two more stars on this ring. Among the scenes from the life of Christ around the octagonal hoop, and on either side of the Baptism, there are stars in two scenes pertinent to this discussion of “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” the Nativity and the Adoration of the Magi (Fig. 5b).

Finally, the fifth gold ring that I want to show you is one of our Featured Works of Art for December 2021 (Fig. 6, Index of Medieval Art system number 200054). This Byzantine ring has been dated to ca. 900, but that date has been questioned.[18] There are niello crosses on the hoop, and on the bezel is a figure in enamel identified by name in niello as St. Nicholas. The image conforms to a familiar type, so we can recognize this figure as Nicholas of Myra. Yes, Virginia, he’s that St. Nicholas.[19]

And so, let St. Nicholas bring this story to a close. It remains only for me, on behalf of all the Index family, to wish you a joyous new year. May 2022 treat you like Ringo Starr…with peace and love.

Contributed by Henry Schilb, Art History Specialist.

Notes:

[1] Mirth without Mischief (London: Printed by J. Davenport, George’s Court, for C. Sheppard, No. 8, Aylesbury Street, Clerkenwell, [1780 or 1800?]), 5–16.

[2] Thomas Hughes, “The Ashen Fagot,” in Household Friends for Every Season, ed. James Thomas Fields (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1864), 34.

[3] Hugh Keyte, Andrew Parrott, and Clifford Bartlett, eds., The Shorter New Oxford Book of Carols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 229.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Frederic Austin, arr., The Twelve Days of Christmas (Traditional Song) (London: Novello, 1909).

[6] The copyright notice is at the bottom of page 2 of the sheet music, and the “five gold rings” motif composed by Austin first appears on page 4. Austin, The Twelve Days of Christmas, 2, 4. See also Keyte, Parrott, and Bartlett, The Shorter New Oxford Book of Carols, 229.

[7] Austin, The Twelve Days of Christmas, 11.

[8] Ioli Kalavrezou et al., Byzantine Women and Their World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 249, no. 141.

[9] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “filigree,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/filigree.

[10] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “granulation,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/granulation.

[11] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “ring,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/ring-jewelry#ref291658.

[12] Robin Cormack and Maria Vassilaki, eds., Byzantium, 330–1453 (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2008), 416, no. 149.

[13] For interpretations of the inscription, see especially Manolis Hadzidakis, “Anneau byzantin du Musée Benaki,” Byzantinisch-neugriechische Jahrbücher 17 (1939–1943): 175–81; Electra Georgoula, ed., Greek Jewellery from the Benaki Museum Collections (Athens: Benaki Museum, Adam Editions, 1999), 316–17, no. 117; and Cormack and Vassilaki, Byzantium, 330–1453, 416, no. 149.

[14] Kalavrezou, Byzantine Women and Their World, 222, no. 121.

[15] For a description of these techniques, see Wolf Rudolf, A Golden Legacy: Ancient Jewelry from the Burton Y. Berry Collection at the Indiana University Art Museum (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 6.

[16] Cormack and Vassilaki, Byzantium, 330–1453, 416, no. 150.

[17] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “niello,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/niello.

[18] Benaki Museum, “Collections & Archives > Byzantine Art,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.benaki.org/index.php?option=com_collectionitems&view=collectionitem&id=107623&Itemid=540&lang=en.

[19] Well, sort of. Readers curious about the journey of Saint Nicholas from Myra to Manhattan will want to track down a copy of Charles W. Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978). Although it’s a fairly old book now, and it was a bit flawed to begin with, it remains nonetheless an engrossing read, a good story well told.

Registration is now open for both online and in-person participation in the Index-hosted conference “Fragments, Art, and Meaning in the Middle Ages” on November 6, 2021. Navigate to our events page for current details about speakers and schedule.

In accordance with campus health and safety guidelines, on-site attendance in Rabinowitz A17 will be limited to those with building access approval from Princeton University, up to a maximum of 50 occupants. Face coverings will be required. All other participants are cordially invited to join the conference online.

Please use the links below for free registration. We look forward to seeing you there!

Use this link for in-person registration

Use this link for Zoom webinar registration

Studies in Iconography 42 (2021)

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to announce that volume 42 of Studies in Iconography, a peer-reviewed scholarly journal hosted by Princeton University and published by Medieval Institute Publications, has appeared both in print and online this year. While physical volumes will continue to be sent to print subscribers on an annual basis, from 2021 onward digital volumes will also be available through Scholarworks, the journal’s new online platform. Past volumes of the journal published from 1993 to five years prior to the current volume will continue to be available via JStor Complete. The current volume includes eight new book reviews and features the following articles:

“A Reconsideration of the Communion of the Apostles in Byzantine Art“

Vasileios Marinis

“Artists and Autonomy: Written Instructions and Preliminary Drawings for the Illuminator in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea (HM 3027)“

Martha Easton

‘A Lanterne of Lyght to the People’: English Narrative Alabaster Images of John the Baptist in Their Visual, Religious, and Social Contexts?

Kathryn A. Smith

“Metapainting in Fourteenth-Century Byzantium and Italy: Performing Devotion Through Time and Space“

Giulia Puma and Maria Alessia Rossi

“Frame for a Sultan“

Rossitza B. Schroeder

“The Implicating Gaze in Bronzino’s Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus and the Intellectual Culture of the Accademia Fiorentina“

Christine Zappella

Journal editors Diliana Angelova and Pamela Patton welcome the submission of original, innovative scholarship on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed, between the fourth century and the year 1600. Editorial guidelines and submission tools are all found on the Scholarworks site.

Attending the 56th International Congress on Medieval Studies this year? Please join us for the two IMA-sponsored sessions on Wednesday, May 12th

190 Wednesday, May 12, 11:00 a.m. EDT: Location, Location, Location: In-Situ Iconography within the Medieval Built Environment I: Topography and Threshold

Location, Performance, History: The West Façade of Wells Cathedral Reconsidered

Matthew M. Reeve, Queen’s University

Of Columns and Column Saints: Architectural Appropriation at Qal’at Sim’an

Laura H. Hollengreen, University of Arizona

“Bearing Witness Then as Now”: Iconography and Epigraphy in the Latin Church of the Holy Sepulcher

Megan Boomer, Columbia University

The Lives of Cats, Eels, and Monks on an Irish High Cross

Dorothy Verkerk, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill

__________________________________

200 Wednesday, May 12, 1:00 p.m. EDT: Location, Location, Location: In-Situ Iconography within the Medieval Built Environment II: The Interior Space

“Feet of Clay”: The Significance of Media and Iconography in Thirteenth-Century English Architectural Interiors

Amanda R. Luyster, College of the Holy Cross

Transfiguring Frescoes: Framing Panel Paintings in Italian Medieval Mural Decoration

Alexis Wang, Columbia University

Folding and Archiving Monumental Images: Bertha’s Tablecloth for the Cathedral in Lyon (Ninth Century)

Vincent Debiais, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris

As of April 1, 2021, the Index-hosted journal Studies in Iconography has shifted to an online submission process, beginning with submissions for volume 43 (2022). Prospective authors may submit their manuscripts on our new Scholarworks site and will find further information both there and in the editorial policies and guidelines section of the IMA website. In addition, beginning with vol. 42 the journal’s annual volumes will be published both in print and online through Scholarworks, a shift that is hoped will increase their reach and accessibility.

Studies in Iconography is an annual journal hosted by the Index of Medieval Art and published in partnership with Medieval Institute Publications. Co-edited by Pamela A. Patton and Diliana Angelova, it presents innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed, between the fourth century to the year 1600. Past and current articles have addressed subjects as diverse as Byzantine fresco programs, Carolingian architectural diagrams, Gothic rent books, Jewish ritual images, Islamicate stucco ornament, and early modern portraiture. We especially encourage article submissions that offer interdisciplinary, theoretical, or critical perspectives, and works of both established and emerging scholars are welcome. Reviews of selected books on iconography and art history are included in every volume.

Inquiries about matters outside the online submission process may be directed to Fiona Barrett, fionab@princeton.edu.

For information about pricing, subscriptions, or back issues, please consult https://wmich.edu/medievalpublications/journals/iconography.

The Index of Medieval Art has completed a systemwide update aimed at making the database both more user-friendly and fully compliant with current accessibility standards. Launched April 1, the update includes the following improvements:

We encourage researchers to explore the updated site, making use of the new Help pages linked on the Welcome page. As always, we welcome your research inquiries and feedback.