By Henry Schilb, Art History Specialist

Is it lost? Was it destroyed? Did it ever really exist at all?

These are questions that we Indexers have to ponder all too often. We try to be both accurate and thorough in our descriptions of the objects in the database, but sometimes we get stumped. Although we Indexers understand that the database we’re building is an invaluable resource—that’s why we do what we do, after all, and we try to do it well—we also understand that there is room for improvement. The Index is neither complete nor perfect. There are gaps and errors in our data, and we know it.

But here’s the thing. In July 2023 the Index of Medieval Art was very pleased to announce that a paid subscription is no longer required for access to the Index database, a change made possible by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the support of the Index’s parent department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University. And now, to celebrate this change, we want to hear from you! Specifically, we want you to tell us what we’ve got wrong. Now that the Index is open to anyone with access to the internet, you can help us correct a mistake, if you find one, or fill in a lacuna in one of our records. It has always been important that we hear from all who use the Index, especially those who know things that we don’t, so what are you waiting for? You can use our Feedback form, or you can also contact one of the Research Staff directly.

Strange as it may seem, one of the most challenging pieces of information to verify is the present whereabouts of an object. As we catalog our oldest records, we sometimes run across works of art that we simply aren’t able to locate. An object’s location is the type of data that can change over time: things get lost; things get sold; things get stolen. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this by giving “Unknown” as the current location. You’ll find hundreds of examples in the Index. When possible we include a “Last Known Location,” the place where an item was last known to exist. A “Last Known Location” can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are lost or in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s current location, that bit of data often eludes us.

So, we’re asking for your help. Here are a few examples:

Can you help us find the piece of gold glass in figure 1? This is the only image we have, an illustration from a nineteenth-century publication. This piece is cataloged as Index system number jkg20200423001, and we have reason to hope that we’ll be able to find this one eventually. You see, a similar piece from the same collection—and illustrated in that same publication—is now in the MFA Boston (MFA accession number 1974.483 and Index system number hds20230131002).

An ivory diptych cataloged as Index system number hds20230620001 presents a similar problem (fig. 2). One wing is now in the Museum Mayer van den Bergh in Antwerp, but the location of the other wing is still unknown. Even the more specialized Gothic Ivories Project at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London lists the location of the left wing as unknown, so it’s not just us. Knowing the location of only one wing of a diptych can be frustrating, but we cling to our hope that we’ll eventually discover the present whereabouts of the other wing.

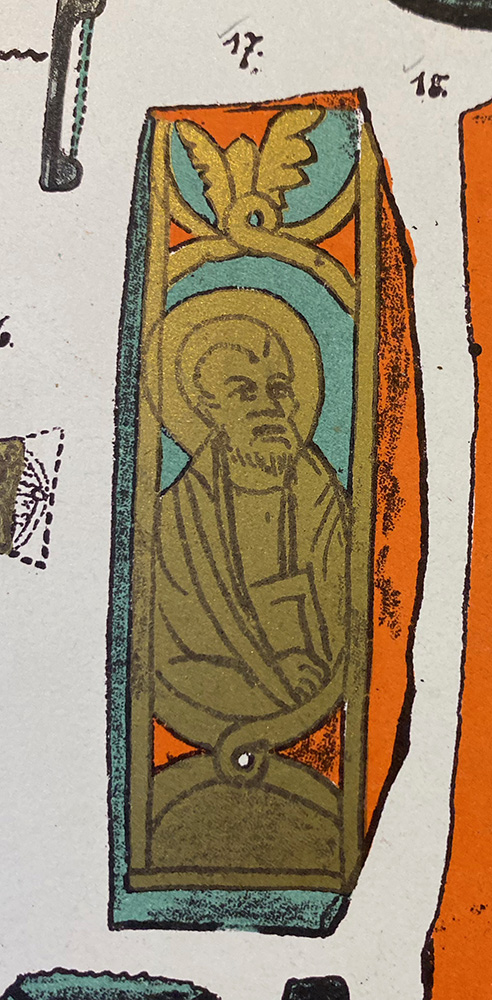

A more extreme example is cataloged as Index system number hds20230712001, an object formerly in the Rumyantsev Museum, Moscow. All the information we have comes from a nineteenth-century publication [Linas, Charles de, “L’Histoire du Travail a l’Exposition Universelle de 1867,” Revue de l’art chrétien 11 (1867): 344–45]. We have no other leads or clues. We don’t even have a photograph or a drawing to go on! Does it still exist? Is it a phantom? Can you help us find it?

Some of these items may still be in private collections; others may have been destroyed at some point after they were first entered into the Index of Medieval Art card catalog; but others may be sitting in storage in some museum in Oz, or Narnia, or even New Jersey, just waiting for you to point us in their direction. Could that be the case for the little chess piece entered in the database as Index system number hds20230330001 (fig. 3)? Formerly in a private collection in Paris, its current location is unknown to us. Is it in Peoria now? Or Paducah? Or even right here in Princeton? If you know the answers to any of these questions—or if you see other gaps that you might be able to help us fill—please tell us! With your help, piece by piece, we’ll make the Index of Medieval Art as accurate, thorough, and up to date as it possibly can be.