Are you familiar with the popular iconography of the saint whose feast day falls on April 23? If you’ve ever been to an English pub, you probably are, even if you didn’t realize it! According to medieval legend, Saint George of Cappadocia was the third-century saint and martyr who slew a dragon. Usually, George is represented as a knight mounted on a horse. Sometimes shown carrying a cross-inscribed shield, his red and white armorial attribute, he thrusts his lance into the jaws of the dragon under his horse’s hooves.

George’s heroic posture was modeled on the iconography of other saints and mythological figures. Theodore Tyro and Demetrius of Thessalonica, for example, also slew beasts in the name of vanquishing evil. Carrying talismanic or protective power for people threatened by worldly dangers, dragon-slayer images decorated many small, portable objects, including ampullae, lamps, carved gems and small plaques from the late antique, Byzantine, and Coptic worlds.1 Building on narratives of his heroism, tales of George’s life and deeds spread throughout medieval Europe with Crusaders returning from the East. By the high Middle Ages, the Golden Legend, a compilation of saints’ lives by Jacobus de Voragine, fleshed out the life of George with a rescue narrative of a king’s daughter and inspired numerous visual representations in different media.2

Depictions of the rescue legend, which follow standard iconography for George’s slaying of the dragon, often insert the princess as a minor character of relative insignificance. But is she insignificant? Traditionally identified as a third or fourth century Komnenian princess of Trebizond, she is sometimes named Sabra or Cleodolinda (or Cleolinda, Cleudolinda) (Fig. 1). According to the legend, the princess was weeping profusely, anticipating her certain death as the next human sacrifice to the dragon, when George arrived at a town called Silene in Libya. He pledged to help her, and he rode toward the dragon with his sword drawn.3 In swift succession, George pierced the dragon and the princess bound her girdle around the beast’s neck. She led it back to the townspeople alive which brought about the people’s mass conversion to Christianity.

In some earlier depictions of the legend, the princess appears with prominence, including on a Romanesque capital from a monastery in Saint-Pons-de-Thomières now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the capital face, the princess wears a long dress, props one hand on her hip, and extends a flower toward George (Fig. 2). Around the other side, George kneels behind his shield, trailing a coiled serpent that approaches the princess from behind. Her thank offering to George in the midst of his attack on the dragon suggests that there will be a good outcome despite the violence surrounding her.

In another Romanesque capital from the abbey of Saint-Pierre of Airvault in Poitou, the princess stands behind George, although he rides away from her, effectively separating her from the dragon’s reach (Fig. 3). With George exiting left, the princess becomes a key figure of interest to viewers gazing upward at the capital. Here, she maintains a stoic stance, and, in ironic juxtaposition with the nearby head of a menacing grotesque, her arms are crossed over her body in a way that suggests patience and perseverance in the face of danger.

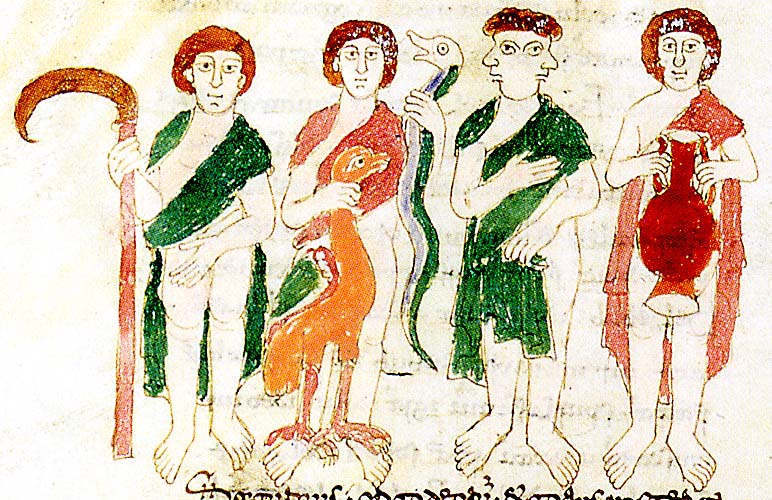

By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the iconography of the princess and her role in George’s slaying of the dragon were handled with more flexibility, especially in manuscript illumination.5 Some examples, such as the Hungarian Angevin Legendary, illustrate the narrative more literally, showing the princess tethering the dragon or leading it away by its makeshift leash (Fig. 4). In this variant of her iconography, the Princess of Trebizond is actively engaged with George’s feat and secures the dragon in one forceful pull.

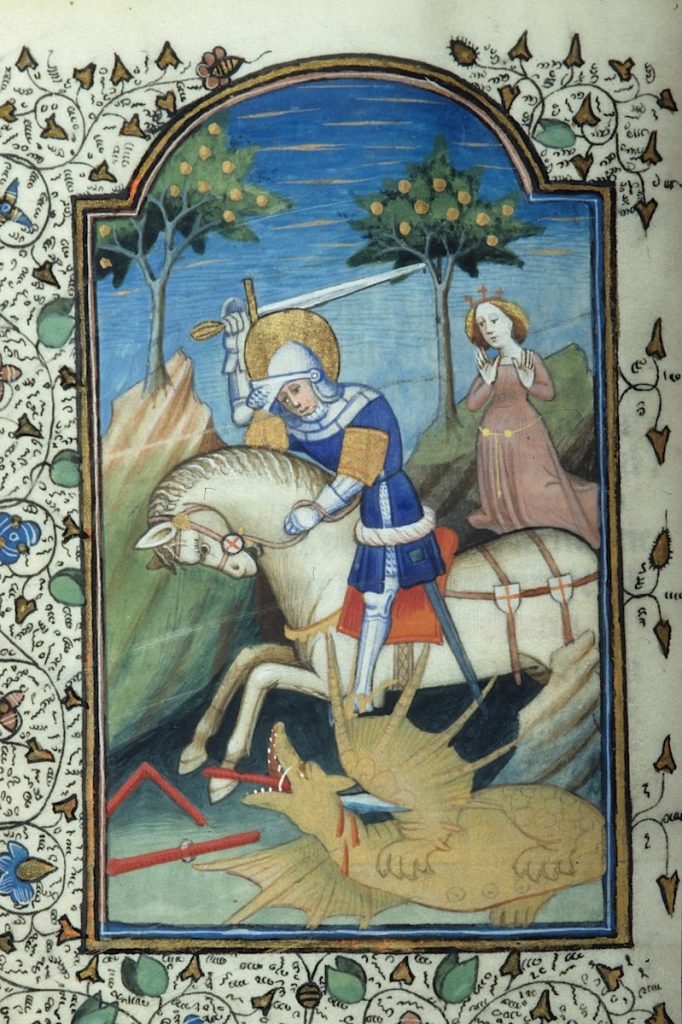

At George’s suffrage in illuminated prayerbooks, especially in Books of Hours, the princess often appears behind the slaying scene, kneeling in prayer, and protected a distance.6 But in some of these late medieval depictions, she tends a flock of sheep, sometimes holding one sheep on a lead, or she simply raises her hands in surprise at George’s victory (Fig. 5).7

In all these images, the princess functions as more than a mere attribute of George. Instead, she is actively reimagined as part of the narrative. Artists creatively customized their images of Georgian legend to not only explore the princess’s instrumental role in her rescue but to highlight her intercessory function in saving the townspeople–in a literal sense and by their newfound faith. Whether showing her as prayerful, gracious, surprised, or tethering the dragon, the iconography of the princess offers a versatile model of female agency, one that likely inspired her viewers.

We can find echoes of such rescue narratives in other ages and media. If you have played the classic Super Mario Bros. video game, then you know the game’s mission: rescue Princess Peach! As aficionados know, the eighth and final world of the game culminated in an underground battle with Bowser, the hammer-hurling, spiky-shelled antagonist (Fig. 6). If you hurled enough fireballs back at Bowser, he overturned and descended into an abyss off screen, allowing Mario to advance over the bridge and reach the princess on the other side. Much like the Princess of Trebizond, Princess Peach had to be rescued, and she, too, has been reimagined over time: her characterization within the Nintendo empire of games and films eventually evolved from damsel in a dungeon to a fighter in her own right.8

You can still find the iconography of George slaying the dragon in the modern world, often in a reduced composition of equestrian, saint, and dragon. Once you know what you’re looking for, you’ll spot George in any number of settings, especially on pub signs like the one on my local haunt when I was a grad student in London (Fig. 7). Whether under his sign or not, those who cheer to Saint George today would do well to remember this: once upon a time, a princess filled with purposeful character also conquered a beast.

Thank You, Saint George! Your Quest is Over.

Appendix

The Index subject files provide a starting point to locate examples of the Princess of Trebizond in the six works of art:

It’s May again, the month that marked the traditional beginning of summer in the Middle Ages. Much as it still is today, this seasonal turn was celebrated with festivals that set aside the toil of spring in favor of games and leisure. In medieval iconography, this time of the year is also captured in a variety of courtship scenes belonging to a genre known as “courtly love.” Such scenes sometimes represented the month of May with depictions of couples playing a game of chess or setting out on horseback for the sport of falconry and hunting, as well as holding merry engagements around fountains or flowing springs. The typical zodiac sign associated with the month of May was Gemini, usually represented by a pair of either twins or lovers, which epitomized the idea of two for this time of year: a double, a match, and a mirror image.

The iconography of mirror and fountains is similar in its ability to emanate personal reflections of a viewer, which made them desirable themes to utilize in courtly imagery. While the idea of gazing at your “twin,” perhaps framed in a window or seated across a chessboard, was celebrated in the Middle Ages, looking at your own reflection for too long, or for the wrong reasons, was frowned upon. A classic warning appears in the tale adapted from Ovid’s Metamorphoses of the mythological Greek hunter Narcissus, who so loved his own reflection that he became fixated on it for life, rejecting all offers of love.

The Narcissus theme is represented in a late fifteenth century miniature in an English manuscript of the Confessio Amantis (“Confessions of a Lover”) by John Gower (d. 1408). The artist depicts a kingly Narcissus wearing a crown, a vair-lined garment, and a jeweled girdle while staring at his own reflection in a fountain (Fig. 1). Narcissus stands in a fenced enclosure surrounded by a unicorn, a collared dog, and a stag. The presence of the stag evokes an Aesopian fable with a similar message, usually called the “Stag and its Reflection” (or the “Proud Stag”), in which a stag admires his antlers in a pool for too long and is caught by the hunter. Like its captive animal companions, the stag echoes Narcissus’s enmeshment in his self-image and ties him to the fountain.

In the popular medieval romance known as the Roman de la Rose, by Guillaume de Lorris (fl. ca. 1230), the “Lover” (Amans) encounters the Fountain of Narcissus and is similarly drawn to look at the reflection of his face in the water (Fig. 2). Like Narcissus, the Lover in the Roman de la Rose is taken with his own beauty in the pool and leans over to admire it; but unlike that of Narcissus, the pool is also the “Fountain of Love,” which destined all who looked in to fall in love. Thus, the Lover’s self-reflection is deeper and more altruistic than his external features, allowing him to overcome the curse of vanity and experience an ideal transformation.

Among the most interesting imagery related to mirrors, fountains, and love is that on Gothic mirror cases, also called valves de miroir. Over seventy examples currently exist in the Index of Medieval Art database, and you can find them by browsing for “Mirror Case” under Work of Art Type. Such mirror cases would twist open to reveal a polished metal disk for personal reflection, while imagery on the closed case told an allegorical story linked with chivalric lore. Mirrors have been part of society since antiquity when they were first made of highly polished stones. The mirror is an essential tool in the iconography of the Toilet of Venus, and it also became both a virtuous attribute for the self-aware personification of Prudence and a sign of vice for that of Vanity. Yet the images carved on Gothic ivory mirror cases rarely warn about the dangers of selfish looking. Instead, they often present scenes of youthful love. On a mirror case in the Walters Art Museum, within the arched portcullis of a castle, a man cups the chin of a woman in a gesture called “chin-chucking” (Fig. 3).

On the Walters ivory mirror back, other young people engage in friendly activities while a group of disabled or elderly persons parade toward the waters of the allegorical “Fountain of Youth” seeking an immortalizing dip. A similar procession of four pairs of men and women meeting at a central two-tiered fountain issuing streams of water appears on a double-sided ivory comb in the Victoria & Albert Museum, made ca. 1400 (Fig. 4). Here, the couples do not gaze into the fountain, nor do they bathe in its restorative waters, but the fountain separates the groups into symmetrical pairs, suggesting an impending connection. The glossy surfaces of mirrors and fountains, with a myriad of possible reflections—of a person’s vanity or deep self-knowing, the promise and capture of love, or the hope of love as a soothing, restorative balm—made these water features the appropriate gathering places for courtly lovers.

The month of May can resemble December for those of us on the academic calendar. The buzz of the semester diminishes to a low hum; there are fewer events, fewer emails to answer, and fewer faces around campus as people take time away from university life. Some might take a break from their work to review their activities and reconnect to individual goals and missions. These yearly transitions can also be times of reflection. Wherever this summer takes you, for work or on trips to faraway lands, we wish you good health and safe travels!

Select Subjects of “Love” Interest in the Index of Medieval Art

The following iconographic headings can be accessed in the Index of Medieval Art Subject List:

Married Pair —The iconographic depiction of a husband and wife together, identified or not.

Marriage—A scene of matrimony or wedlock celebrating the union of two people as they become spouses.

Castle of Love—The “Castle of Love” allegory is associated with the iconography of chivalry and courtly love and is often represented on fourteenth-century ivory mirror cases and caskets. Also known as the Siege (or Attack) on the Castle of Love, it typically includes the God of Love (Eros or Cupid) holding a bow and arrow and positioned on the top of a castle while women, couples, and lovers defend the tower, sometimes by tossing roses on battling equestrian knights below.

Courting—Index subject incorporating various scenes of courtly love, including crowning lovers, or couples chin-chucking, also used in combination with scenes of falconry, hunting, or chess.

Couple—The term to describe a pair of people, usually a man and woman depicted as lovers.

Falconry—Also known as “Hawking.” The sport of hunting with predatory birds is especially associated with the iconography of the Labors of the Month for April and May and scenes of courtship with figures and couples holding the birds of prey.

Fountain of Love—An allegorical fountain for courting lovers as described by the fourteenth-century French composer Guillaume de Machaut.

Fountain of Youth—An allegorical fountain or spring which, according to legend, had the power to restore youth to anyone who bathes in its waters.

Labors of the Month, May—The occupation for the month for May, usually represented by an outdoor scene of courting or the sports of hunting and falconry, often by equestrian couples. Variants of this scene include the courting lovers walking in a landscape, sometimes holding hawks, falcons, flowers, or branches, or sometimes depicted in a scene of merriment involving musicians.

Mirror—A polished surface, often held by a handle or decorative frame, and reflecting a clear image of what it is pointed at. Attribute of the vice personification of Vanity. Sometimes held by the goddess Venus.

Sexual Activity—The subject for figures engaging in any explicitly sexual activity. Often suggested by two people lying down in close proximity to each other, possibly nude, possibly embracing each other, and sometimes in a bed.

Further Reading

Camille, Michael. The Medieval Art of Love: Objects and Subjects of Desire. New York: Abrams, 1998.

Hult, David F. “The Allegorical Fountain: Narcissus in the ‘Roman de la Rose.’” Romanic Review, 72, no. 2 (1981): 125–50.

Lewis, C. S. The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Peklar, Barbara. “The Imaginary Self-Portrait in the Poem Roman de la Rose.” Ars & Humanitas 11, no. 1 (2017): 90–105.

Other Resources

The British Museum. “A ‘Greatest Hits’ of medieval myths on a casket | Gothic Ivories 1 | Curator’s Corner S7 Ep4.” YouTube Video, 11:57. June 23, 2022. https://youtu.be/IA0sWopdLxs.

Gothic Ivories Project at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Accessed February 14, 2023. http://www.gothicivories.courtauld.ac.uk/.

By Jove! This year a special planetary alignment will occur on December 21st, also the Winter Solstice, when earth’s northern pole is at its greatest tilt away from the Sun. During this “Longest Night,” the planets Saturn and Jupiter will be within a tenth of a degree to one another, appearing to form a single “star.”

While an alignment of Saturn and Jupiter happens about every 20 years, when it happens in 2020 it will be one of the closest alignments of these two planets for over 800 years, and by some accounts since the year 1226.[1] The 1226 Saturn-Jupiter conjunction coincided with several historical milestones. In France, the reign of Louis IX, the only French king to be canonized by the Catholic Church, began following the death of his father Louis VIII. In Norway, the cleric Brother Robert translated the popular chivalric romance of Tristan and Iseult into Old Norse at the request of King Haakon IV. In the Kingdom of Georgia, the Sultan Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, last ruler of the Khwarezmian Empire, captured Tbilisi in the Battle of Garni. The mendicant friar, preacher, and later saint Francis of Assisi died on October 3rd. And according to Canadian astronomer and historian Vibert Douglas, the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan abruptly ended his military campaign in China, possibly owing to the phenomenon of five separate planetary conjunctions over the years 1226 and 1227.[2]

In the Middle Ages, the seven “planets”—Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Mercury, and the sun and moon—were important celestial bodies in the heavenly realm. Each was thought to have a distinctive personality, an idea still reflected in Gustav Holst’s orchestral suite The Planets, composed between 1914 and 1916. Holst calls Jupiter “The Bringer of Jollity” and Saturn—colloquially also known as “Father Time”—“The Bringer of Old Age.” These names doubtless influenced the artistic expression in the series of dance performances for Holst’s Planets by the Princeton University Ballet in 2018 linked above.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, was initially named after the ancient Roman god of thunder, and its planetary neighbor Saturn, the god of agriculture and harvest, was also Jupiter’s father. In Greek mythology they are Zeus and Cronus and were sometimes represented by medieval artists as luminous pointed stars, or solid spheres in concentric circles of earth-centered astronomical diagrams, as in this later copy of a Byzantine geocentric model of the cosmos (Fig. 1).

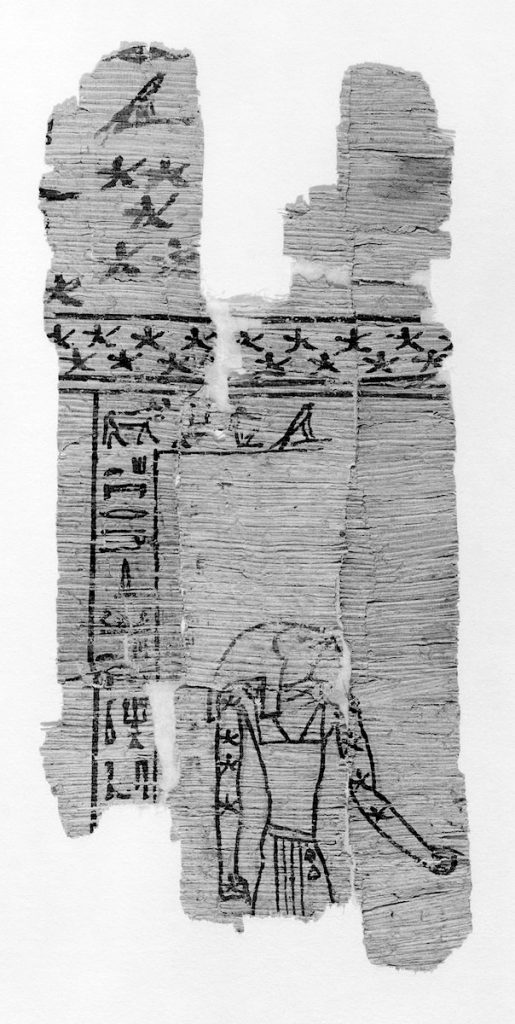

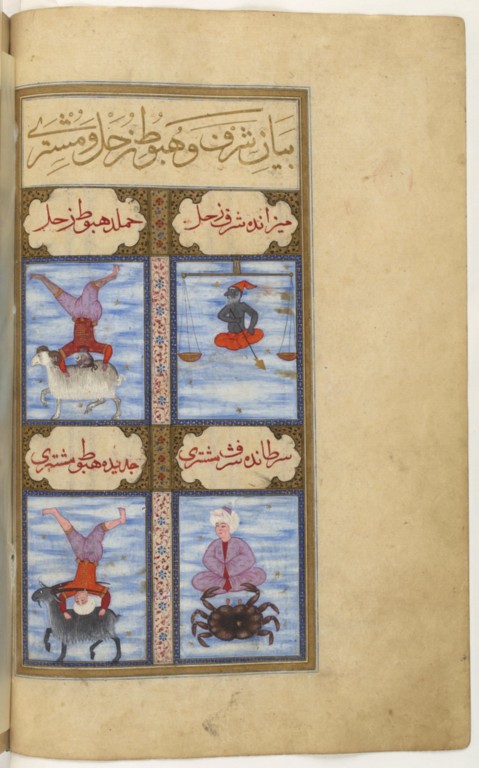

Representations of the planets are found in the artistic traditions of many cultures in which astronomy was an important science, including the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hellenistic, Indian, Byzantine, Islamic, and Chinese spheres. A possible early figuration of the planet Saturn can be seen on this ancient papyrus fragment in the Metropolitan Museum of Art as an Egyptian deity (Fig. 2). A much later figuration of the planets is found in this sixteenth century “Book of Felicity” (Matali’ al-saadet) made for Sultan Murad III (r. 1574–1595), now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which contains images of the “exaltation” and “dejection” of the planets—that is, when they are in apogee and perigee (Fig. 3). On folio 33v, Saturn’s exaltation in Libra is represented by the zodiacal scales, and his dejection in Aries shows him falling headfirst onto the back of a ram. The lower two vignettes similarly depict Jupiter’s exaltation in Cancer by pairing him with the zodiacal crab, and his dejection in Capricorn by tumbling onto a goat.[3]

In western European art, the planets were presented both as heavenly bodies and in symbolic form. In this late medieval manuscript of the Confessio Amantis (“The Lover’s Confession”) by John Gower, a small miniature of the planetary system, prefacing the part on Astronomy, contains the sun and moon with human faces among five gold and starry planets, the uppermost two labeled with their Latin names “Saturnus” and “Iubiter” (Fig. 4).

In Dante’s Divina Commedia, the spheres of heaven were represented by planets; Saturn was the seventh sphere and Jupiter the sixth. In this illustration of Paradiso 22, the scene of the “Heaven of Saturn” is portrayed by Beatrice and Dante welcoming five nude souls descending a ladder from a glowing red star with seven points (Fig. 5). Reading the Paradiso, we know that this level of heaven was reserved for the contemplanti, or the founders of monastic orders, “men who were kindled by that heat which brings to birth the blessed flowers and blessed fruits.”[4]

In other medieval works the planets of the cosmos (and sometimes their children!) were personified as human figures.[5] In some of the earliest examples, planets were depicted as crowned figures, triumphant generals, or wearing laurels, rayed headpieces or wings; such types appear on Roman coins and as bust-length personifications in illustrated poems known as carmina figurata.[6]

Some representations evoked the temperaments often associated with each planet. Associated with the ambivalent nature of melancholy, Saturn was often configured as an old man with a handheld sickle (or a more “modern” scythe) and with a cloak draped over his head, but he can also hold a shovel, a wheel, and small nude figure, which he raises up as if to devour, a reference to the Greek myth in which he swallowed his children.[7] Jupiter was seen as a protective deity: his iconography varies from the classical, bearded archetype of “Zeus Pater” (Zeus the Father), who brandishes lightning bolts, a celestial wheel, or other symbols of his power, to his personification as a bishop in a late fifteenth-century astronomical miscellany in the Getty Museum.[8]

In classical mythology it was held that Jupiter drove Saturn away from his celestial throne. A marginal scene in this ninth century Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen depicts this dramatic argument of the ancients (Fig. 6). Saturn is pursued by Jupiter both wielding an axe, illustrating the First Invective against Julian the Emperor, “… let Jove rebel against Saturn, following his sire’s example; that sweet stone and bitter slayer of tyrants …”[9] In an early eleventh century manuscript of Rabanus Maurus’s encyclopedic De Universo, one miniature depicts Saturn with a scythe, nearly as tall as he, and Jupiter holds a symbolic pair of attributes: an eagle for deified justice and a serpent representing the age-old struggle for it (Fig. 7).

Two highly emblematic representations of the planets Jupiter and Saturn appear in the Rheinish manuscript of the Von Dem Gang des Himmels und Sternen (“The Course of the Heavens and Stars”), forming its own “planetary conjunction” at the close of the book (the miniatures are on facing pages). Both planets, Saturn personified as a simple farmer and Jupiter as city patrician, are decorated with imagery from a number of astrological and zodiacal sources, including their corresponding symbols for Libra and Cancer (Figs. 8 & 9).

The Index of Medieval Art database includes much more in the way of celestial imagery, including subjects related to the iconography of the other planets, stars, zodiac symbols, and constellations. The database also can be keyword searched for other named astronomical objects, such as “Star of Bethlehem.” These examples appear in a wide variety of works of art, including almanacs, calendars, astrological treatises, constellation maps, zodiac cycles, and a variety of narrative and allegorical works, and across different media, cultures, and periods.

The planetary motions of Saturn and Jupiter have been described by astronomers, such as Newton, Kepler, and Laplace, as “The Great Inequality,” meaning that while Jupiter’s mean period of motion is continually increasing, Saturn’s is continually diminishing and falling further behind.[10] Thus, both planets have long been approaching each other in the same direction, yet with enormous discordance.

The year 2020 has had its own prelude of tumultuous moments leading up to this great planetary conjunction. As the globe still grapples with a challenging year, it’s easy to imagine this alignment of Saturn and Jupiter as a sort of “clash of the titans,” but when we look west in the sky just after sunset, let us recall that this special occurrence, a most rare ballet of the planets, also marks a new season that will bring more light to our days.

[1] O’Neill, Mike. “Don’t Miss It: Jupiter, Saturn Will Look Like Double Planet for First Time Since Middle Ages.” SciTechDaily, 23 Nov. 2020, https://scitechdaily.com/dont-miss-it-jupiter-saturn-will-look-like-double-planet-for-first-time-since-middle-ages/; Strickland, Ashley. “Jupiter and Saturn Will Look like a Double Planet Later This Month.” CNN, Cable News Network, 3 Dec. 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/12/03/world/jupiter-saturn-conjunction-2020-scn-trnd/index.html; Levenson, Michael. “Jupiter and Saturn Head for Closest Visible Alignment in 800 Years.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Dec. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/06/science/space/jupiter-saturn-align-christmas-star.html.

[2] Douglas, A. Vibert, “Historical Significance of Five Conjunctions, 1226–27,” Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 65 (1971): 129–132.

[3] See also this exquisite engraved and inlaid brass tray with personifications of planets made by Mamluk craftsmen and commissioned by a Sultan in Yemen in the early fourteenth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.1.60). For more on astronomy and astrology in the medieval Islamic world, see this essay by Marika Sardar: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/astr/hd_astr.htm.

[4] Paradiso 22, 47–48 accessed at Barolini, Teodolinda. “Paradiso 22: Controlled Orphism.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2014. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-22/. See also the Princeton Dante Project https://dante.princeton.edu/pdp/, with recent news and developments on the project here, https://humanities.princeton.edu/2020/11/29/2020-rapid-response-grant-literary-visualizations-reconstructs-imaginations-of-dantes-readers/.

[5] Discussion of the planets and their characteristics, temperaments, and affinities are found in many almanacs, planet books, and other cosmological treatises. See especially the classic Warburgian study by Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art (London: Nelson, 1964). Reissued by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019.

[6] The Index database records three examples of planetary carmen figuratem, all in the British Library, MS. Cott.Tib.B.V (fol. 44v), MS. Cott.Tib.C.I (fol. 33r), and MS. Harley 647 (fol. 13v).

[7] Klibanksy, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 197.

[8] For the Jupiter-Bishop on horseback see Getty Museum, MS. Ludwig XII 8 (83.MO.137), fol. 49v. See also the Art Stories post by Bryan C. Keene, “Written in the Stars: Astronomy and Astrology in Medieval Manuscripts,” Getty Iris Blog (30 April 2019), https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/written-in-the-stars-astronomy-and-astrology-in-medieval-manuscripts/.

[9] See lines 120–121: Gregory Nazianzen, “Julian the Emperor” (1888). Oration 4: First Invective Against Julian. The Tertullian Project, 14 Dec. 2020, http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/gregory_nazianzen_2_oration4.htm.

[10] Wilson, Curtis, “The Great Inequality of Jupiter and Saturn: From Kepler to Laplace,” Archive for History of Exact Sciences 33, no. 1/3 (1985): 15–290.

As the fall 2020 semester begins and the Index staff continue to work remotely, each of us connecting from different locations, our home libraries and desks have become essential tools in our research. They call to mind medieval images in which the scribe’s desk and well-stacked bookshelves are familiar iconographic attributes of the Evangelists, as well as theologians, scholars, physicians, and literati, as they labored in their study spaces (see Index subjects: Bookcase, Scholar, Physician, Literatus, and Philosopher Type). Their desks took a variety of forms and shapes, from tall book stands or lecterns, sometimes decorated with animals, birds, and foliage, to round or squat tables of a simpler design. Medieval images of scribes and writers often show the surfaces of their desks covered with open books or sheets, some with scrawled lines (search Index keyword: pseudo-inscriptions), inkhorns and inkpots, knives, pen cases, and a spare stylus or two.

Working in a modern study space, many of these similar tools are within my reach: pens, scissors, a pencil cup, and plenty of Post-it Notes containing my jotted reminders—arguably legible! My computer desktop is a hub for images of medieval works of art, articles, and spreadsheets that help organize my Index work. To the right of me, sits a modest collection of tomes (to name a few, Emile Mâle’s Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages; Roger Wieck’s Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art; Baxter’s Bestiaries and Their Users in the Middle Ages, and the catalogues The Splendor of the Word and The Golden Age of Ivory Gothic Carvings in North American Collections). Some books are my own and some are out on temporary loan from the Index’s research library and from Firestone Library, but all are bolstering this new environment of cataloguing and scholarship from home.

For Index research staff, this means that our working desktops (both physical and virtual) and our carefully curated home libraries (whether lining our walls or nested digitally into desktop folders) will support our ongoing remote activities. This semester, we will continue to pursue new art historical research for additions to the database, including works from the original print backfiles, from monumental mosaics to illuminated manuscripts and ivory objects. We remain focused on expanding the Index collection to present the rich array of iconography from the global Middle Ages. We will also continue to refine the database by building and improving work of art location authorities, further developing Index subject classifications that improve thematic browsing, and implementing the new hierarchical browse tool for researching the placement of medieval iconography within structures. Above all, we will remain available to support researchers at all levels in their use of the online Index database.

Wherever you may be this term—whether you feel like a monk in a cell or a monkey with an inkpot—we hope that you are well and looking forward to your study, surrounded by the tools of your scholarship. We look forward to hearing how we can help serve your research and teaching in the upcoming academic year.

In northern climes, the beginning of February used to be reliably miserable. It was always the time of year when the sedentary heart of winter was covered in forgetful snow, and we took refuge indoors while the wasteland outside was feeding a little life with dried tubers (to paraphrase T.S. Eliot). Groundhog Day is in early February for a reason. Every year, in our collective longing for an early return of spring, we eagerly anticipate the meteorological insights of a skittish marmot. And so, despite the unseasonably warm temperatures in Princeton this week, we couldn’t help but explore some imagery traditionally associated with the month of February.

In many manuscript calendar illustrations, the occupational image for February depicts an interior scene, a room in which figures warm themselves before a fireplace. Seated at the hearth, a female servant, or perhaps the woman of the house, stokes the fire. Often in such scenes, a man sits at a table spread with food and dishes. The Index of Medieval Art subject heading identifies this scene as the “Labors of the Month, February.” Certain components of this subject, such as “Fireplace,” “Table,” and “Feasting,” also have their own subject designations.

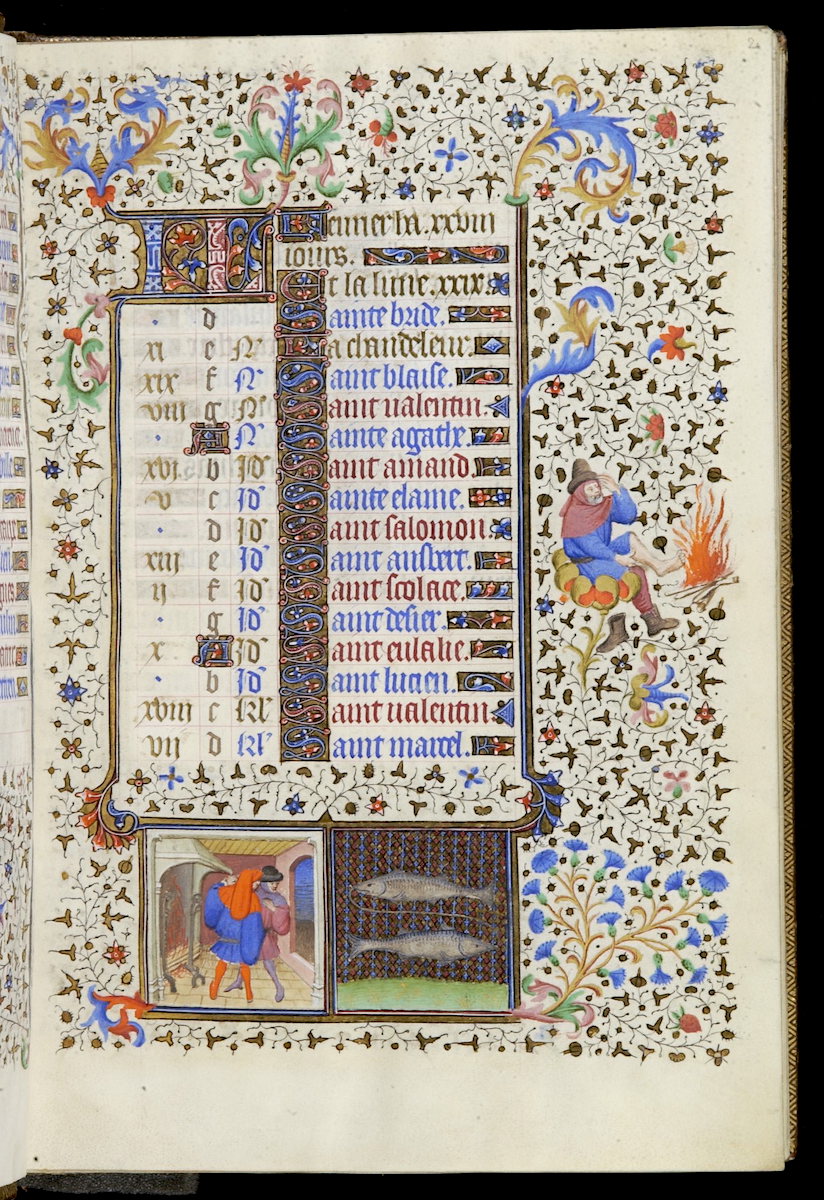

Other attributes common to the February warming scenes are figures performing such actions as blowing a bellows at the fire, cooking food in a pot over the flames, carrying bundled firewood indoors, or wearing heavy furs. A marginal miniature in the calendar of a fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Burgundy depicts a typical February scene with several of these domestic elements: a woman wearing a veiled headdress stokes a glowing fire in a simple stone fireplace while, behind her, a warmly dressed man seated at a draped table clings to a morsel of food (Fig. 1).

Searching the Index of Medieval Art database with simple keywords such as “fireplace,” and using the Subject Filter for “Labors of the Month, February,” will return a little more than seventy work of art records. Most of them appear in illuminated manuscripts. One such fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Paris or Flanders contains a February calendar page with two square miniatures of equal size in the lower margin. One of these paired miniatures shows the typical interior occupation of February, figures by the fire. The other shows the usual zodiac sign, Pisces, as a pair of fish lying head to tail with a line connecting them by their mouths. In the right margin, the artist created a comical moment: among the densely scrolled foliate borders, a man sitting on a fantastic flower raises his bare left foot toward some blazing logs (Fig. 2). In February, even marginalia need to warm their toes!

Other database filters will discover results illustrating February in different media, such as a man warming himself in the quatrefoil stone relief sculpture on the west façade of Amiens Cathedral. While this February figure sits and adjusts logs on the fire, his shoes are neatly placed in the foreground (Fig. 3). As is common for all twelve labors of the months, iconographic variants occur among these images, and monthly tasks are not fixed. Indoor cold weather occupations—including feasting, cooking, and baking—can be found in the previous months of January and December, often in similar compositions with fireplaces. February illustrations may also show outdoor scenes, such as slaughtering animals, fishing, digging fields, or pruning vines.

Keeping warm and dry during the winter months was a matter of survival for medieval people. Even today our good health and happiness are at risk in the winter. While its fires are long extinguished, this fine fifteenth- or sixteenth-century French limestone fireplace, today on display in the Met Cloisters, was likely once the architectural centerpiece of a home, and we can still imagine its appealing warmth (Fig. 4). Whether you are enjoying a restfully sedentary season or the official start of the spring semester has you thoroughly engaged in your own labors of the month, we wish you a warm and happy February!

As a victorious angel, defender, and leader of heavenly armies, Michael the Archangel is often depicted in medieval art as an armored soldier carrying such arms as a cross-inscribed shield, cross-staff, or the sword or spear he typically employs to fight the dragon in the “great battle of heaven” (Apocalypse 12:7–9; see the Index subject Apocalypse, Dragon Attacked by Michael). Outside of the apocalyptic combat scene, Michael also may be shown trampling and piercing the dragon as part of his overall iconography. This figuration of Michael as the triumphant archangel lent a devotional and meditative aspect to his veneration as an overcomer of evil, as is often clear in images related to the Christian feast of Michaelmas. The feast’s name in English derived from “Michael’s Mass” and is traditionally observed in some Western churches on the 29th of September. While Michaelmas was primarily celebrated to acknowledge the works of Michael the Archangel, this feast also celebrated the help and intercession of all angels. Michaelmas also bore secular significance for medieval people as a “quarter day” of the financial year, which signaled the fulfillment of various business obligations, and the close of the agricultural year (For more on this holiday, see Ben Johnson, Michaelmas, The Blog of Historic UK).

At this time of Michaelmas, a dive into the online collection of the Index of Medieval Art reveals a wealth of examples tied to the iconography of the revered archangel. The most common representation is of Michael the Archangel fighting the dragon. In the language of the Index, that’s Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Dragon. This subject heading is attached to nearly 300 works of art in the database applied to a variety of media, including a Romanesque limestone relief panel from Burgundy, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris (Fig. 1). A closely related subject, Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Satan, is applied to works of art in which the dragon has morphed into a devilish creature, usually shown with horns and clawed feet. Like the hapless dragon, this creature is similarly impaled and trampled! Exploring these two similar subjects reveals a later preference for the literal depiction of devils in place of dragons. Michael the Archangel also features in other important episodes, such as the biblical narrative of the Fall of Angels and the Last Judgment of Christ (Figs. 2 & 3). In Last Judgment scenes, Michael the Archangel is often shown holding the scales of justice laden with good and bad souls (See the Index subject Weighing of Soul).

A fifteenth-century alabaster panel from England combines many aspects of Michael’s typical iconography: here, wearing a suit of armor that resembles feathers, he also bears a shield and raises his sword over the vanquished dragon. One weighing pan of his scales remains, holding a devil head, while behind him, a crowned Virgin intercedes to emphasize mercy with justice (Fig. 4).

In the Index database, Michael the Archangel is by far the best represented of the archangels, with thirteen subjects covering his various roles, from intercessor and commanding soldier to apparition in visions and legends. A common legendary context for Michael is that of the “Runaway Bull” in the Golden Legend. According to the legend, a wayward bull belonging to Garganus, a wealthy man from Siponto, is miraculously saved from the shot of an arrow, which instead reversed in midair and killed the huntsman. As an explanation for this strange occurrence, Michael the Archangel appears to a local bishop to reinforce the idea of grace at the bull’s saving and to tell him to build a church in his honor (Fig. 5). The hilltop sanctuary of San Michele del Gargano is still a popular site of pilgrimage in the town of Monte Sant’Angelo in southern Italy.

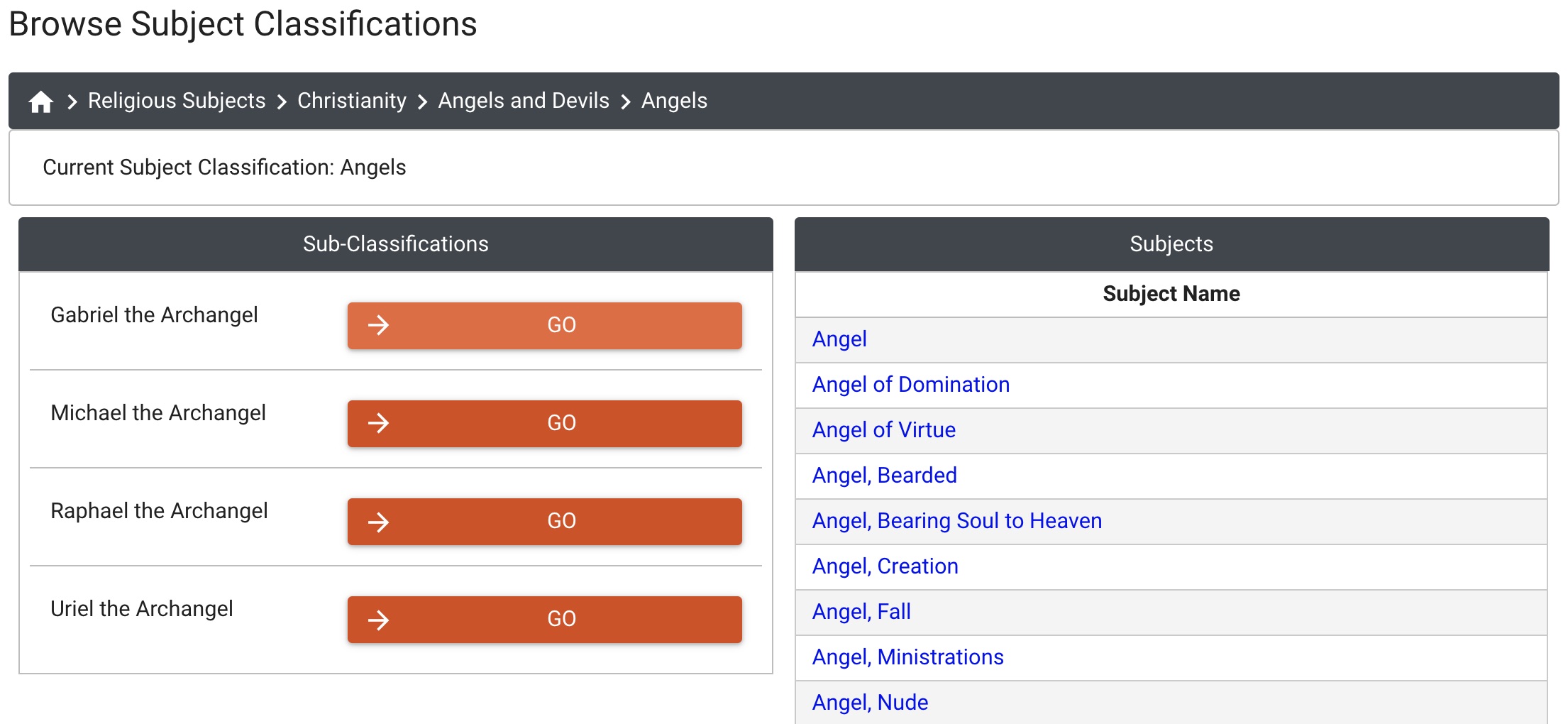

For a more general overview of the iconography of angels in the Index database, we encourage you to browse sections of the new subject classification network by clicking “Browse” and proceeding to the link for “Subject Classification.” From here, click on Religious Subjects, then Christianity, then Angels and Devils. In the sub-group of Angels, you will encounter a list of over twenty iconographic headings associated with various angels, including seraphs, cherubs, and several more subjects for angels engaged in specific actions, such as “Protecting Soul” and “Pursuing Devil.” On the left are further divisions for the four major archangels of Christian angelology—Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, and Michael—which list the individual subjects related to each. At the bottom of each authority for these subjects, you’ll see a bar for “Work of Art References” that will take you to the relevant work of art records.

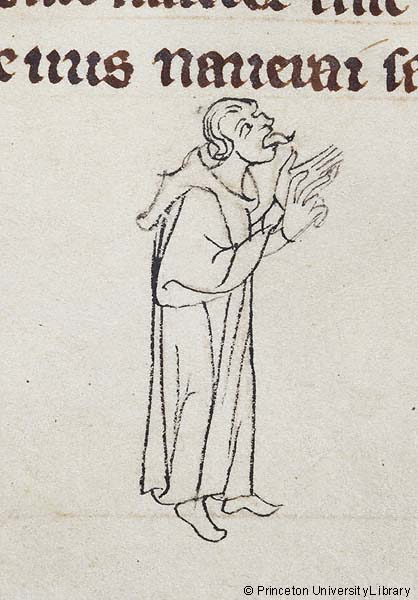

King David is well represented in the Index of Medieval Art database, with close to 200 subject headings covering the various scenes of his life. He is most often depicted as a richly garmented king, often with his role as the psalmist suggested by his signature harp and crown. One variant of his iconography, which I encountered while cataloguing a historiated initial from an early sixteenth-century French Psalter, presents a familiar subject in the life of David, described by the Index as David, Communicating with God (Fig. 1). However, in this example, the kneeling David adds an extra gesture to his prayer routine. Where one would expect to find reverent folded hands, David emphatically points his finger to his protruding tongue!

While studying this initial, I decided to use the tools in the updated Index database to explore how David’s pose and the purposeful indication of his tongue were related to the psalm verse. In this Psalter, the initial D for Dixi begins Vulgate Psalm 38, verse 2: Dixi custodiam vias meas; locutus sum in lingua mea posuri ori meo custodiam cum consisteret peccator adversum me… (Douay-Rheims Bible, accessed 22 February 2019, http://drbo.org/). Translated, this reads “I will take heed to my ways, that I sin not with my tongue. I have set guard to my mouth, when the sinner stood against me.” The tongue is mentioned one more time in this psalm at verse 5 with regard to speech, “I spoke with my tongue: O Lord, make me know my end. And what is the number of my days: that I may know what is wanting of me” (drbo.org). The image of David thus prefigures the textual passages of the psalm in that both image and text suggest the speaking and offending capabilities of the tongue. But, how often do we see David depicted with his tongue sticking out? And can we find other contexts for his expressive gesture?

I entered a simple keyword search for “tongue” in the upper right search bar on the Index database homepage and used the Subject Filter to refine my results to David, Communicating with God. Immediately, I located a much earlier scene from a Parisian Bible in the Morgan Library dated to the first quarter of the thirteenth century (Fig. 2). This initial D, also beginning Psalm 38, encloses a beardless, crowned David, looking up toward the face of God and mirroring the action of raised finger to outstretched tongue.

Since both of these images open Psalm 38, the presence of magnified tongues seems intended to show that significant body part that David was obliged to “sin not” with.

This connotation of the image is better understood in the context of the medieval preoccupation with the peccata linguae, or “sins of the tongue,” such as those assigned to fallen characters in the Divine Comedy and the Roman de la Rose. These transgressions of speech include flattery, duplicity, evil counsel, discord, and blasphemy. Medieval moralists also were concerned with sinful tongues: the Franciscan John of Wales (d. 1285), for example, wrote a preaching treatise called De Lingua (“The Tongue”), which outlined the proper duties of a “good” tongue as to share in ethical knowledge and to oppose its own natural “bad” inclinations.

In medieval art, depictions of sinful tongues like David’s can be found in figural representations of Slander, False Seeming, and other personifications of vice. A figure identified as the Unmerciful Judge sticks out his tongue in the lower margin of a 15th century Manuel des Péchés to illustrate the Exemplum, or lesson, for the Sins of Avarice and Covetousness (Fig. 3). His long, curled tongue and raised hands suggest how insistently he imparts this lesson on the vices. However, his prominent tongue is also inherently tied to his cruel speech, offering a visual metaphor of merciless judgment.

Wishing to investigate further the iconography associated with Psalm 38, I used the Index database to browse through the numbered psalms in the Subject Browse List. Clicking the subject heading for Psalm 039 (Vulg., 038) revealed that a majority of the illustrations depict David pointing to his mouth, a common way to represent speech, but without his tongue sticking out. One such initial appears in the Noyon Psalter, attributed to the Master of the Ingeborg Psalter, in the J. Paul Getty Museum (MS. 66, fol. 41v). This suggests that the literal representations of David’s tongue were the more unusual depiction. To take this theory a step further, I repeated the keyword search for “mouth” and refined the subject to David, Communicating with God. This search yielded about 30 examples where David was indicating his closed mouth, a subject that is particularly common in manuscript initials associated with Psalm 38.

Medieval commentaries on Psalm 38 help to explain the popularity of this iconography. Theodoret’s Commentary on Psalm 38 notes the text’s emphasis on the sinfulness and “lowliness” of human nature and humanity’s need for deliverance, while Augustine wrote of the same psalm that, although the tongue was “prone to slip,” bridling it will help one stand against wicked enemies. Both commentators connected Psalm 38 to an episode in Samuel, where David was viciously pursued by Absalom and abused by Shimei, who threw sticks and stones at him while he fled from Jerusalem. That biblical narrative itself is sometimes found illustrating Psalm 38 (see the related Index subject heading David, Cursed by Shimei). In a manuscript of the Enarrationes in Psalmos, dating to the mid twelfth century, a historiated initial P encloses a crowned David covering his mouth while Shimei hurls stones at him (Fig. 4). Here, David’s cautious gesture and muted tongue show his restraint from sin, shedding light on the meaning of the gesture when it appears in the psalm initials.

Finally, I decided to broaden my search to locate all depictions of this particular body part with David. I repeated the keyword search for “tongue” and set the Subject Filter to David. This led me to a historiated initial in the twelfth century English manuscript of the Saint Albans Psalter and to another layer of iconographic context. Here, the initial E for Erucatavit, beginning Vulgate Psalm 44, encloses a seated and crowned David, who raises a pen in his right hand and with his left index finger points to his extended tongue (Fig. 5). Written in red ink above the incipit is the rubric Lingua me calamus scribae, taken from verse 2 of that Psalm, which can be translated as, “My tongue is the pen of a scrivener”(drbo.org). This verse of Psalm 44 is preceded by the mention of David’s verbum bonum, or the “good word” uttered from his heart to the king (mea regi), suggesting that goodness issues from him and through him, by way of tongue and pen.

With regard to this Vulgate Psalm 44, Augustine comments,

What likeness, my brethren, what likeness, I ask, has the “tongue” of God with a transcriber’s pen? What resemblance has “the rock” to Christ? (1 Corinthians 10:4) What likeness does the “lamb” bear to our Saviour (John 1:29), or what “the lion” to the strength of the Only-Begotten? (Revelation 5:5)

(Augustine, Expositions, Digital Psalms version, p. 264)

Today, we enjoy ample use of emojis, which add expressive meaning to our messages to one another. In the Middle Ages, manuscript illuminators did not miss the opportunity to illustrate textual passages with similarly expressive visual cues in images, which also linked to the complex layers of meaning readers anticipated finding in the psalms. Although David’s gesture to his closed mouth seems to be a relatively common composition, the emphasis on his stuck-out tongue in certain depictions speaks just as expressively of its sinful capabilities as it does of its usefulness as an obedient tool.

The investigation of David’s “emoji” highlights how researchers can look for specific iconographic motifs in the Index by combining keyword searches in the description field and filtering with controlled headings in Advanced Search options. For advice on your own research topic and forming search strategies using the Index database, send us a Research Inquiry. We’ll be 🙂 to hear from you!

Sources

Baika, Gabriella I. “Lingua Indiciplinata: A Study of Transgressive Speech in the ‘Romance of the Rose’ and the ‘Divine Comedy.’” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2007.

Craun, Edwin D. Lies, Slander, and Obscenity in Medieval English Literature: Pastoral Rhetoric and the Deviant Speaker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. See especially pp. 33–34.

Douay-Rheims Bible. Accessed 22 February 2019. http://drbo.org/.

Gellrich, Jesse M. “The Art of the Tongue: Illuminating Speech and Writing in Later Medieval Manuscripts.” In Virtue & Vice: The Personifications in the Index of Christian Art, 93–119. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. See especially pp. 108–109.

Hill, Robert C. “Commentary on Psalm 39.” In Commentary on the Psalms, Psalms 1–72, 233–36. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2000. St. Aurelius Augustine. Expositions on the Psalms, Digital Psalms version 2007, 205–216, 262–277. Accessed 22 February 2019. https://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/otesources/19-psalms/text/books/augustine-psalms/augustine-psalms.pdf. See especially pp. 205–206, 264–265.

Matthew’s Gospel tells us that, at the moment Christ died, darkness swept over the land for three hours (Matthew 27:45). The foreboding skies at Christ’s crucifixion were also recorded in Luke 23:44-45 and Mark 15:33. Mark’s account, thought to have been written around the year 70 CE, was likely the earliest.[1] Some scholars have reasoned that this midday phenomenon was an actual eclipse, because the passage in Luke reports that darkness fell over the land when “the sun was eclipsed” (“τοῦ ἡλίου ἐκλιπόντος”) (Luke 23:45). However, the passage is usually translated “the sun was darkened.” The verb is in the passive voice, as is the verb “ἐσκοτίσθη” used in other versions of the Greek text, and both words can mean “was darkened” or “was obscured.”[2] No matter how we may interpret the words relating the phenomenon, and no matter whether it is possible to attribute the darkness thus described to a real astronomical event, scriptural hours of daytime darkness over Golgotha presented an iconographic opportunity to medieval artists depicting the Crucifixion.

In manuscripts and painted works of art that aimed to depict the event, color was frequently exploited to illustrate darkness and to create a dramatic setting. Across media, the celestial bodies of the sun and the moon were incorporated into the skies above the crucifixion, not only to signal darkness at daytime but also to imbue the scenes with a rich cosmological significance.

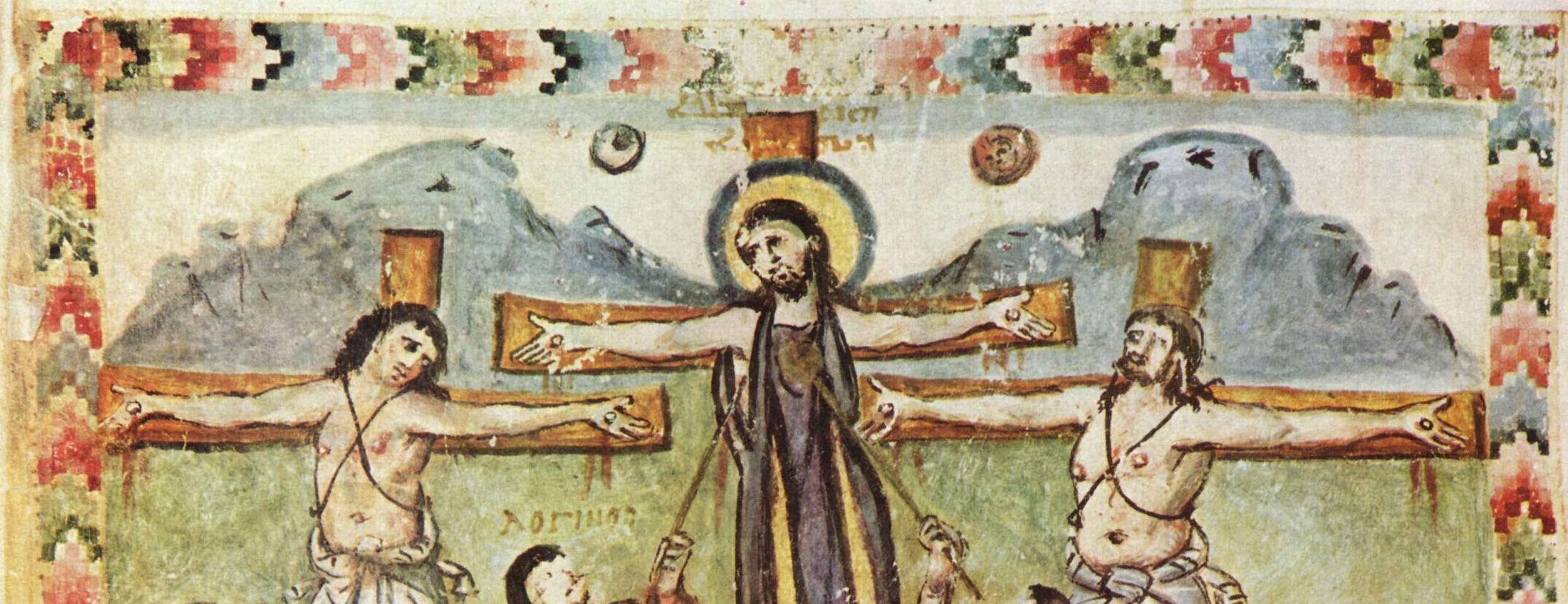

An especially early example appears in the Syriac Rabbula Gospels from the late sixth century. In this manuscript, the Crucifixion includes a partly eclipsed Sun and a Moon with a face against a remarkably light sky; a sliver of shaded pigment at the top suggests darkness (Figure 1). From antiquity, the sun and moon were associated with power. In early medieval crucifixion scenes they represented God’s cosmic anger at the death of Christ.[3] Throughout the Middle Ages, personifications of the Sun and Moon became regular characters at the Crucifixion, positioned as sorrowful figures mourning Christ’s death. The placement of the Sun and Moon respectively at the right and left arms of the cross came to be read typologically as the Old and New Testaments.[4] After about 850, they could also be seen as allegorical representations of Church and Synagogue.[5]

The Ottonian Sacramentary of Henry II sets the Crucifixion scene against a deep purple background, a striking hue used to set a somber mood and suggest darkness (Figure 2). Busts of the personifications Sun and Moon sit on the arms of the cross. The Sun, labeled SOL and sporting a rayed headpiece, and the veiled Moon, labeled LUNA, both turn away from the scene and weep into their draped hands. The strong background color effectively conveys the darkness of this scene emphasized by the dramatic gestures of the Sun and Moon.

Medieval artists sometimes set the same iconographic features within a flattened space of gold or patterned backgrounds. A leaf from the Potocki Psalter, made in Paris in the mid-13th century, sets the Crucifixion against a gold background (Figure 3). Christ is flanked above by the sun and moon and below by the Virgin Mary and the Evangelist John. Within this composition, the three main figures hover between time and space, darkness suggested only by the presence of the partly obscured sun and the crescent moon.

Similarly, in a Crucifixion scene painted around 1400 to 1410 in a Register of Coiners and Minters from Avignon, a richly patterned background of gold scrolls avoids any illusion of a dim sky (Figure 4). The red sun and the moon’s countenance in the upper corners of the miniature are the only clues that the ornamental ground is actually simulated “darkness.” In both miniatures, decorative and luminous backgrounds highlight the central features of the scene so that the Crucifixion image becomes a place of mediation, the background “darkness” metaphorically positioned between an earthly space and a shift in the cosmos at the moment of Christ’s death.

Images of darkness at the Crucifixion can be found in the Index database by any of several possible search strategies. One method is to perform an advanced search using the keyword “Crucifixion” while filtering with the subject “Sun and Moon.” This search returns over 380 results. Executing the search again with the subject “Personification: Sun and Moon” returns around 220 examples in a variety of media, including ivory plaques, glyptics, and frescoes. “Personification: Sun and Moon” is the subject used by the Index for records concerning works on which both celestial bodies have facial features. Using words like “stars” or “starry,” background elements that can also suggest a dark sky may be recorded in the Index’s descriptions of such works.

With the advent of the Index of Medieval Art’s new database, thumbnail images are now visible with search results, allowing the researcher to review works of art at a glance. Thus, a researcher looking into images of the Crucifixion will be able to notice the gradual change in the later medieval period in the West, when images of the Crucifixion began to represent the three-hour darkness as a true night sky. In a Book of Hours made in Paris about 1490, a soft pattern of gold stars with the sun and moon dot a dark blue sky to create the illusion of evening (Figure 5). Other Crucifixion scenes that a researcher may notice while thumbnail browsing show cloudy, dark, and emotive skies that convey darkness without the sun or moon. These atmospheric scenes offer a remarkable and naturalistic, if not peaceful, departure from the earlier ones with their grief-stricken personifications of the Sun and Moon.

The starry night sky casts a familiar source of light over a recognizable scene, and these astronomical bodies inspired fascination in medieval minds still forming theories about what those bodies might actually be. Nevertheless, the symbols of the Sun and Moon, while signaling darkness and the passage of time, also imparted emotional weight, persisting in iconography not only to adhere to scriptural tradition, but also to emphasize the significance of Christ’s death.

Further Reading

Hautecoeur, Louis. “Soleil et la lune dans les crucifixions.” Revue archéologique, ser. 5, XIV (1921): 13-32

Schiller, Gertrude. “The Crucifixion.” In vol. 2 of Iconography of Christian Art, 88–164. London: Lund Humphries, 1972.

Nickel, Helmut. “The Sun, the Moon, and an Eclipse: Observations on The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, by Hendrick Ter Brugghen.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 42 (2007): 121–24.

[1] The Gospels report three other supernatural events that occurred during the Crucifixion: the temple veil was split in two; various earthquakes shook the land; and the souls of the dead rose from their graves. See related subjects in the Index of Medieval Art: Christ: Crucifixion, Earthquake; Christ: Crucifixion, Resurrection of Dead, and Veil of Temple: rending.

[2] Bible Translation. “David Robert Palmer trans., The Gospel of Luke: Part of The Holy Bible.” Accessed 30 March 2018. Bibletranslation.ws/trans/lukewgrk.pdf. See especially p. 116, n. 307.

[3] Gertrude Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, trans. Janet Seligman (London: Lund Humphries, 1972), 2:94.

[4] This interpretation was promoted by St. Augustine (354–430 CE). Schiller, 109.

[5] Schiller, 110.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the feast of the Presentation of Christ was observed on February 2nd, where it gradually absorbed the rites of the Purification of the Virgin.[1] Incorporating blessed candles and certain songs, the feast came to be known as Candlemas. The only gospel writer to describe the Presentation of Christ in the Temple was Luke in the second chapter of his Gospel account (Luke 2:22–39). Luke writes that, in accordance with Jewish tradition, parents were required to bring an acceptable offering in exchange for the priest’s redemptive blessing on their child. Luke notes that “a pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons” would fulfill the sacrifice (Luke 2:24). In Presentation scenes, the gathered doves, usually held by Joseph, signal Christ’s restoration under Mosaic Law. Over time, lit candles at this same ritual came to mark the Virgin’s cleansing and reentry into the temple.[2] In a stained-glass window in Canterbury Cathedral, we find Joseph holding both implements at the far left, a visual sign of the combined purpose of their visit (Figure 1).

When the Holy Family approaches the altar, Luke records two mystical occurrences that concern key witnesses in the temple. First, Simeon, the named priest from Jerusalem, prophesies the divinity of the Christ Child.[3] Another prophetic utterance comes from the lips of an unlikely source, the temple’s aged widow, Anna the prophetess. Luke tells us that Anna fasted and prayed there without ceasing. Anna is the New Testament’s only prophetess, and her privileged glimpse of the important ritual uniquely connects her to the childhood of Christ.

The Presentation is Anna’s one shining moment in the Gospels. In the Index of Medieval Art there are over 960 examples of the subject Christ: Presentation, and at least 330 include Anna as a secondary figure in the scene. We discover varied depictions of Anna in these medieval images. She is depicted as a scroll-bearing prophetess; as proxy to the presentation ritual, handling the different ritual items; or she may be simply shown among the other women surrounding the Virgin Mary. Despite her prominent role at the Presentation of Christ, Anna’s portrayal in medieval images can be perplexing. It seems medieval artists, who knew about her visionary role at the Presentation, could choose to emphasize or de-emphasize Anna as a prophetess based on tradition, context, or perhaps even their own interpretations of her significance. Several Presentation scenes also include a woman near the altar, and Indexers have often identified her as a female attendant, questioning her identity as the prophetess in iconographic descriptions.[4] Thus was born the usual Index reading of this female figure: “probably Anna.”

Because of the inconsistency of representations of the Presentation, it is not always easy to identify Anna in medieval images. Moreover, Luke’s account offers few details about her, other than that she is:

Analysis of Presentation scenes does reveal a few key details consistently associated with Anna: the presence of a halo; her scroll, which expounds her part in the prophecy; her interaction with presentation/purification implements, including the doves and candles; and her advanced age, sometimes suggested by her modest wimple. One or more of these details could be enough for a positive ID of our prophetess. Another sign is her speaking gesture, as in the Presentation miniature in the Romanesque Mont-Saint-Michel Sacramentary, in which Anna’s hands are shown outstretched in a wide statement of praise (Figure 2). This miniature also exemplifies an iconographic conundrum that sometimes accompanies Anna: a second nimbed and veiled female figure stands just behind Joseph, and she is carrying two doves in draped hands. Is this a second Anna? Or is this simply a sanctified female attendant? This female assistant is doing what many later Annas do in bearing the sacrificial birds, so the context with which we identify Anna becomes increasingly important.

Anna is one of the first people, even the first woman, to reveal Christ’s destiny, but her exact words are omitted from Luke’s account. We know that she “spoke of him to all that looked for the redemption of Israel” (Luke 2:38). However, since Anna’s actual words are not recorded, her scrolls present a number of different inscriptions. An Index search reveals some of the most intriguing ones. In the fifth-century sanctuary apse mosaic at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, Anna’s scroll is inscribed BEATVS VENTER QVI TE PORTAVIT (Luke 11:27), meaning “Blessed is the womb that bore thee.” In a late twelfth-century mosaic in the Cathedral of Monreale, Anna holds a scroll inscribed POSIT(US) EST HIC I(N) RVINA(M) (Luke 2:34), repeating the words first said by Simeon, “This child is set for the fall.” In a fifteenth-century panel by the artist known as the “Byzantine Painter,” Anna holds a scroll inscribed (in Greek) “This child created Heaven and Earth” (Figure 3). And in one emotive declaration in a ca. 1240 Psalter from Hildesheim, Anna’s scroll is inscribed in Latin, EXULTATUIT COR MEUM (I Samuel, 02:01, also known as the Canticle of Anna), meaning “My heart hath rejoiced” (Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. Don. 309, fol. 37r).

Anna’s scroll has even been used to identify her by name, as in the presentation scene on the ca. 1365 Florentine Ashmolean Predella, from a private collection in Tuscany, with a scroll inscribed “ANNA PROFETESSA DEO GRATIAS AMEN” (“Prophetess Anna, Thanks be to God”). In this case, Anna’s index finger is elegantly lifted upward to indicate from whom her proselytizing originates. In other examples, Anna’s scroll can be completely blank, or filled with a pseudo-inscription. In the Armenian T’oros Roslin Gospels, the scroll expands into neat folds revealing simple red rulings (Figure 4).

The new advanced filter options offered by the Index database can reveal interesting trends within the Anna images recorded by the Index. I performed a keyword search for “Anna,” filtering by the subject Christ: Presentation, and restricted the search to fifteenth century examples (setting the date slider at 1400 to 1499). I limited these examples further with the Work of Art Type filter set to “Manuscript.” This way, I found over 60 records of interest describing fifteenth century illuminations that include this scene.

I narrowed these results further by adding a second subject filter with one of the Index’s grouped terms, Candle: held by Prophetess Anna. I found that, with each refinement, I was able to reconstruct Anna’s changing representation in medieval iconography. Curiously, in several of these late medieval examples, Anna is holding both a candle and a dove, and she is directly behind the Virgin Mary (not Simeon), displacing Joseph completely. These three-character scenes of the Presentation make up a good portion of later examples, and they underscore Anna’s union with the Holy Family’s first official appearance. In one such image, a fifteenth-century Book of Hours made in Paris, Anna is holding a candle in her right hand while playfully balancing a basket of birds on her head. A talented multitasker, Anna has, in a sense, usurped Joseph’s gift-bearing role (Figure 5).

No matter how she appears—as a wise widow bearing her scroll, or as a female witness bearing the implements of the impending ritual—the prophetess Anna is an exemplary New Testament woman. Through her time-honored vows of chastity, piety, and obedience to God, virtuous qualities brought out in her varied iconography, she presents a model of behavior for the young mother.

Further Reading

Shorr, Dorothy C. “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple.” The Art Bulletin 28, no. 1 (1946): 17–32.

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art, vol. 2, The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, trans. Janet Seligman (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1972): 90–94.

Elliott, J. K. “Anna’s Age (Luke 2:36–37).” Novum Testamentum, 30, Fasc. 2 (Apr., 1988), 100–102.

Hammond, Joseph. “Tintoretto and the ‘Presentation of Christ’: The Altar of the Purification in Santa Maria Dei Carmini, Venice.” Artibus Et Historiae 34, no. 68 (2013): 203–217.

“Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple.” In The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art & Architecture, edited by Murray, Peter, Linda Murray, and Tom Devonshire Jones: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Witherington III, Ben. “Mary, Simeon or Anna: Who First Recognized Jesus as Messiah.” Accessed 2 February 2018: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/mary-simeon-or-anna-who-first-recognized-jesus-as-messiah/

Notes

[1] From at least the fourth century this ritual was celebrated as a post-purification feast, known as Hypapante, which Justinian set 40 days after the feast of the Epiphany, or on February 14.

[2] For the best study of the development of this iconography, see Dorothy C. Shorr, “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple,” Art Bulletin 28 (1946): 20–46.

[3] Simeon holds the infant in his arms and instantly says to the Virgin Mary, “Behold this child is set for the fall, and for the resurrection of many in Israel…,” and representations of Simeon are associated with the text Nunc Dimittis, also known as the Canticle of Simeon (Luke 2:34–35).

[4] Shorr notes that, in most northern medieval examples after the thirteenth-century, Anna’s place was taken over by a young handmaiden (Shorr, 1946, p. 27).

While the other months of the year had specific harvesting tasks associated with them, the relative ease of May was a welcome relief from the daily toil that dominated medieval life. May occupations are traditionally represented as more joyous, particularly in Books of Hours and Psalters. The Index database records over 180 scenes for May in manuscripts, and a little over half of them use the occupation of the male falconer on horseback (see related subjects: Month, Occupation: May; Figure, Male: Falconer; Horseman: Falconer; and Scene, Sports and Games: Falconer). Falconry, or Hawking, was a favorite medieval sport enjoyed especially at the beginning of spring. These hunting birds were prized for their agility and loyalty to their masters. Another popular scene depicting May is a pair of lovers on horseback, occasionally with a bird perching on the man’s wrist. This scene of a riding couple was a favored occupation and signaled the readiness for new courtships. Other instances of May scenes include figures holding flowers or wreaths, couples promenading, and other verdant scenes of courtship, whether amid blooms in grassy gardens or even on boats (see related subject: Scene, Secular: Courting).

The zodiac sign that commences in May is Gemini, traditionally represented by a pair of figures—Gemini being Latin for “twins”—that are linked to their astrological appearance in the sky (see related subjects: Zodiac Sign: Gemini and Constellation: Gemini). The representations of Gemini can also be divided into a few main categories. A sample of about 80 French medieval manuscripts reveals that the most popular Gemini sign was the embracing nude couple, with far fewer of them appearing clothed. Often the couple’s bodies are masked by parts of the landscape or are cropped by a frame. Nude twins are the second most common Gemini sign and are usually depicted as two men embracing or wrestling. Sometimes the twins will appear as confronted soldiers with mirrored weapons and gear. The twin variations in Gemini also include pairs with crossed legs, conjoined bodies, or even one figure with two heads.

The subjects for months and zodiac signs are most prevalent in manuscripts, but they are also well-represented in sculpture such as the famous façades at Chartres and Vézelay. In 2007, information on all zodiac and occupation subjects classified by the Index was collected and published with Penn State University Press as Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months and Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art. This book has been hailed as a “lavishly illustrated” and “functional research tool” for studying the subject of the medieval measuring of time.

Hourihane, C., ed. Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months and Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2007.

Neal, K. “Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months & Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art (review).” Parergon, vol. 25 no. 2, 2008, pp. 164-166.