The medieval church season of Lent officially opened with Ash Wednesday, the Wednesday after Quinquagesima Sunday (the period of fifty days before Easter). The observance of Ash Wednesday marked forty fast days before Easter, not counting Sundays. During Lent, medieval Christians were forbidden to consume meat, eggs, dairy and animal fats, except on the permitted Sundays which were viewed as a “mini-Easter.” By adding a level of restraint to their daily lives, medieval Christians fulfilled a call for penance, which was especially important during the Lenten season. On Ash Wednesday, in the Middle Ages as it is now, a celebration of Mass incorporated the distribution of blessed ashes on the foreheads of believers. When dispensing the ashes, the celebrant reminds those receiving it that “as you are from dust, from dust you shall return” (based on Genesis 3:19).

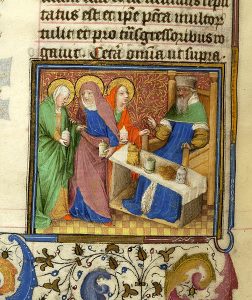

The Index records three examples in manuscript illumination of the distribution of ashes. Each begins a part of a liturgical book read for this feast: a Gradual fragment in Princeton University Library (Kane 13), a Gradual in the Morgan Library (M.933), and a Missal in the Walters Art Museum (W.174). The Morgan and Princeton Graduals begin with the same Latin Introit, “Misereris omnium domine et nichil odisti eorum…” (Thou hast mercy upon all, O Lord, and hatest nothing…). It is interesting to note that the subject heading “Scene, Liturgical: Distribution of Ashes” used by the Index now was not in the original card file but was developed sometime during the last twenty years when post-1400 material was incorporated into the Index.

The marketplaces of medieval Europe were redolent of the spices that purportedly first arrived with returning Crusaders. A taste for the flavors of cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, ginger, pepper and the like created an increasing demand for spices that could not be grown in Europe’s climate but had to be imported from the East along secret trade routes, over land and sea. Distance was only one of several factors that affected the supply of spices, which were expensive and enjoyed only by those who could afford them. Nevertheless, as Paul Freedman writes in his blog “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced our World,” the new taste for exotic flavors helped encourage world exploration and turn spices into global commodities.

The uses of spices were both culinary and medical, and medieval cookbooks and herbals reveal that spices were part of preferred regimens. Spices were taken together in varying combinations, sometimes seasonal. In the cold and wet winter months, it was advisable to eat spices in strongly flavored food and drink to warm the body. Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat notes in her History of Food that the physician Arnau de Villanova (c. 1240-1311) recommended balancing the four humors of the body by consuming spices “proper for winter” as zesty sauces of ginger, clove, cinnamon, and pepper (Toussaint-Samat, 486). These spices would aid digestion after a heavy winter meal by heightening the effects of “hot” and “humid” properties in roasted meats. To this day, the warming spices advocated by Arnau de Villanova tend to be associated with fall and winter.

Cameline sauce, perhaps the original steak sauce, was the perfect accompaniment to roast meats. Prepared in summer and winter months alike, the sauce was so popular in some locations, such as fourteenth-century Paris, that the blend was usually readily available from the local sauce maker. There were regional varieties of Cameline sauce, too, and the “Tournais style” involved grinding together ginger, cinnamon, saffron and half a nutmeg. The spice powder was soaked in wine and stirred together with bread crumbs. The strained mixture was then boiled, with sugar added to make the winter variety of the sauce. One recipe for Cameline sauce has been adapted by Daniel Myers for the Medieval Cookery web site and is reproduced here with permission.

Cameline Sauce

3 slices white bread

3/4 cup red wine

1/4 cup red wine vinegar

1/4 tsp. cinnamon

1/4 tsp. ginger

1/8 tsp. cloves

1 tbsp. sugar

pinch saffron

1/4 tsp. saltCut bread in pieces and place in a bowl with wine and vinegar. Allow to soak, stirring occasionally, until bread turns to mush. Strain through a fine sieve into a saucepan, pressing well to get as much the liquid as possible out of the bread. Add spices and bring to a low boil, simmering until thick. Serve warm.

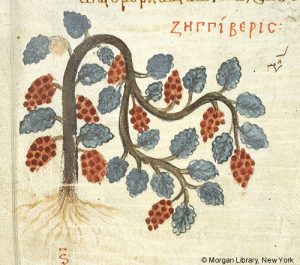

Ginger came to be highly prized during the Middle Ages, though the use of ginger can be traced back thousands of years in India and China. The potent ginger plant and rhizomes were valued for their stomach-warming and digestive properties as much as for the flavors they imparted. The first-century Greek physician Dioscorides advocated consuming a spicy Arabian plant called ζιγγίβερις (zingiberis), which was probably ginger, to “soften the intestines gently.” In Arabia, Dioscorides noted, they used only the freshest ginger plants (O’Connell 116-117).

Clove was known as one of the “lesser spices.” Though not as strong as ginger but useful for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties, clove was especially useful in dental care.

Named in English and other languages—“clou de girofle” in French—for the resemblance of the bud to nails, clove originated in the Moluccan Islands of Indonesia, the historical core of the Spice Islands. As with ginger, clove had its earliest uses in India and China in the fourth-century BCE, finding its way to Roman and Greek markets by way of port cities on the Mediterranean. By the eighth century, clove was known throughout Europe and features in several historic dishes. It was also a typical spice in pomanders, the medieval precursor to potpourri, in which fragrant ingredients were placed in a perforated box to ward off illness. The decorative use of clove-studded oranges, a seasonal pomander, is still associated with the winter months.

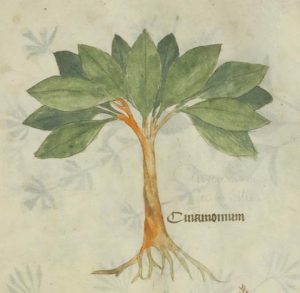

Hippocras, or hypocras, was a medieval spiced wine and popular cordial enjoyed especially during the winter holidays for several centuries. Hippocras was a concoction of powdered cinnamon, cassia buds, ginger, grains of paradise and nutmeg boiled with sugar and wine. Cinnamon, the essential flavor of hippocras, was a favorite spice of the medieval palate. Its mysterious origins generated many fanciful tales and even several expeditions. Perhaps most famously, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus thought he had located the spice in America—the Indies to him— and in 1493 he reportedly brought back bits of bark from a perfumed wild cinnamon tree that was not very tasty.

Long before Columbus, the ancient Egyptians had prized cinnamon as the “… goodly fragrant woods of The Divine Land…” while medieval Arabs believed that large birds used cinnamon sticks in their nests (O’Connell, 76-77). In the first century, the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder rightly located the origin of cinnamon on the shores of the Indian Ocean. With information from some seasoned merchant, perhaps, Pliny knew that the cinnamon trade was dangerous and that a return trip to the source of the spice took almost five years. Pliny’s claims about the origin of cinnamon were eventually verified in the 1340s when the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta (1304–c. 1368) arrived at the island of Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) and discovered untouched miles of the cinnamon tree. Before its widespread appreciation as a culinary ingredient, cinnamon was prized in several ancient cultures as incense holding ritualistic importance, sometimes burned for its fragrance on a funeral pyre.

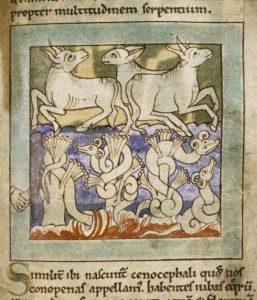

The final “proper” winter spice is pepper. With a name widely applied to many spices, including the black and white varieties, pepper was perhaps the most familiar spice of the Middle Ages. Both black pepper and white pepper are obtained from the small berries of the Piper nigrum vine.

Unripe berries are green, and ripe berries are red. Dried ripe berries yield white pepper, and despite the fantastic medieval legend propagated by Isidore of Seville (560–636) that the scorching of pepper crops blackened the berries and drove out the poisonous guard snakes, unripe pepper berries are simply plucked, gathered, cooked, and then dried to give us the most familiar variety, black pepper. The principal traders of pepper came from India where the vines thrived in tropical regions. Pepper was used in medicine to aid digestion and to treat ailments like gout and arthritis, as well as infectious diseases like the bubonic plague.

The term “peppercorn rent” derives from the practice established in early common law in England that payment of rent or tax might be made by a peppercorn, to avoid the bother of exchanging real currency. Usually no peppercorns were actually collected during these transactions, but the spice represented a hard asset, and the term is still in use today in legal parlance to describe a token amount of rent money paid in order to keep a title alive. In all seasons, spices and their increasingly globalized trade during the Middle Ages affected medieval economies, and brought social, culinary, and health benefits to Europe. To this day, the flavors and aromas of medieval markets spice up the long, cold winter months.

Sources

Paul Freedman, “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced Our World,” The YaleGlobal Online Blog, March 11, 2003, http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/spices-how-search-flavors-influenced-our-world.

Daniel Myers. “Cameline Sauce.” Medieval Cookery. Last modified July 13, 2006. http://medievalcookery.com/recipes/cameline.html.

Freedman, Paul. Out of the East: Spices and Medieval Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Translated by Anthea Bell. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Leah Hyslop, “Where do Christmas spices come from?” The Telegraph.co.uk (blog), December 22, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/grow-to-eat/where-do-christmas-spices-come-from/

O’Connell, John. The Book of Spice: From Anise to Zedoary. London: Profile Books, 2015.

The governing offices of medieval church and state – such as emperor, king, pope, archbishop, abbot, mayor, and so on – were often filled by election, in accordance with public and canon law. Often, election by a voting body facilitated the peaceful transference of power, even if such decisions also considered the privileges of birth and rank, as well as the requirements of the church.

Under canon law, medieval people were guaranteed certain human rights, including welfare rights, the right of certain classes to vote, and religious liberty (Helmholz 3). Canonists supported the free exercise of these rights, as they believed them to be supported by biblical tradition. Common law, or ius commune, upheld that a right order of government on earth was based in natural law and the upholding of these God-given rights. In effect, common law and canon law were seen as linked systems, to be enforced at the highest level to promote God’s plan for the world. Voting rights were recognized under both systems, so that secular elections evolved from the system put in place by medieval canonists for choosing offices within the church (Helmholz 6).

Medieval elections took place primarily in three contexts, ecclesiastical, secular and academic, but detailed evidence about them is scarce. Voting in both ecclesiastical and secular elections could follow one of four main procedures: overseen by an external authority with no direct interest in the election; by indirect election, in which electors named a proxy to select the officials; by lot; and by ballot (Uckelman and Uckelman 3). In contrast to most modern practice, electors had a limited choice, and the outcome of an election was always subject to the judgment of their superiors. Medieval law also ruled that all of the electors had to meet at the same time in the same place, whether or not the actual voting was done in secret. This was to mimic the meeting of the apostles at Pentecost and to wait for divine guidance before voting (Helmholz 8).

For some medieval rulers, the election, crowning, and anointing of Old Testament kings proved to be an excellent model for legitimizing their rule. Biblical tradition not only provided a justification for absolute reign, it also ensured that the church remained authoritative over secular rulers. In principle, the selection of a medieval monarch was based on both elective and hereditary elements, but from the tenth century in northern and central Europe, political and social trends steered toward hereditary succession over an elective monarchy (Nelson 183). This trend is exemplified in a French manuscript titled the Avis aus Roys, or royal advice book, dating to the mid-fourteenth century and possibly made for Louis, Duc d’Anjou (1339-1385). This book highlights the benefits of adhering to hereditary royal succession, which was widely seen as a more secure and manageable transference of power than other means of selecting a ruler.

The Church’s rules for filling ecclesiastical offices presented a paradox, as they strongly favored a mix of election and hierarchy. Before the papal bull In nomine Domini of 1059, which included an election decree, the pope’s successor was most often named by the incumbent pope or by secular rulers (Larson 151). Reforms put in place over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries resulted in the creation of the first papal conclave (1276) and College of Cardinals, the familiar process for electing the pope that is still in practice today. Below the pope were elected cardinals, archbishops, bishops, and other local offices for priests and deacons. Episodes of their ritual consecration, ordination, vesting, installation, and taking orders feature prominently in the Index subject headings. Another elective office common in the Middle Ages was that of abbot or abbess of a monastery.

Among the more numerous depictions of Benedict of Montecassino delivering rule to monks is a rare episode in an Italian manuscript depicting him chosen as abbot. In this Vita Benedicti, dating to the mid-fifteenth century, a miniature depicts a group of monks presenting a letter, stamped with a dangling wax seal, to the new abbot-elect standing in the doorway of his mountain monastery.

The Index collection includes many images of election-related imagery, including depictions of medieval leadership, kingly coronations, ecclesiastical consecrations, synods, and deliberating monks. Typical subject headings include David: proclaimed King, Solomon: crowned King; Simon Thassi: chosen Leader of Machabees; Edmund of England: Scene, Coronation and Consecration; Guillaume de Machaut, Livre du Voir Dit: Scene, King addressing Court; and Louis of Toulouse: Scene, taking of Orders.

Sources

Benson, Robert L. The Bishop-Elect: A Study in Medieval Ecclesiastical Office. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Barzel, Yoram, and Edgar Kiser. “The development and decline of medieval voting institutions: A comparison of England and France.” Economic Inquiry 35, no. 2 (1997): 244-60.

Uckelman, Sara L., and Joel Uckelman. “Strategy and manipulation in medieval elections.” Accessed in http://ccc.cs uni-duesseldorf. de/COMSOC2010/papers/logiccc-uckelman. pdf (2010), 1-12.

Helmholz, Richard H. “Fundamental Human Rights in Medieval Law.” (Fulton Lectures 2001): 1-18.

Nelson, Janet L. “Medieval Queenship.” In Women in Medieval Western European Culture, edited by Linda E. Mitchell, 179-208. New York and London: Routledge, 2011.

Weiler, Björn. “8 things you (probably) didn’t know about medieval elections.” History Extra Blog. N.p., 6 May 2015.

Larson, Atria. “Popes and Canon Law.” In A Companion to the Medieval Papacy: Growth of an Ideology and Institution, edited by Atria Larson and Keith Sisson, 135-37. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

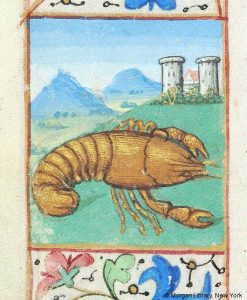

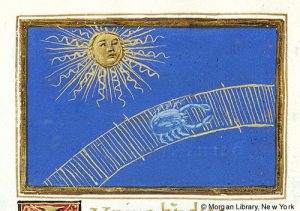

On June 21st we recognize Cancer, the astrological sign that Richard Hinckley Allen called the most “inconspicuous figure of the zodiac” (Allen, 107). Representing the sun at its highest point, Cancer is the zodiacal sign of the summer solstice. In ancient Egypt, the Cancer sign was imagined as a scarab beetle, and in Mesopotamia as a turtle or tortoise, both of which may have pushed the sun across the heavens. In Europe, traditionally, the constellation of Cancer was identified with the crab from Greek mythology that was crushed by the foot of Hercules and placed in the sky by Hera. Some have speculated that the characteristic sideways walk of hard-shelled crustaceans, whether crayfish or crab, could be symbolic of the backward shift in day-length after the arrival of the summer constellation in the Northern Hemisphere at the end of June, and Medieval people also believed those born under Cancer’s influence harnessed great, gripping power.

At the Index of Christian Art, the label “lobster-like” has been used to describe Cancerian crabs that are not at all “crab-like.” These crustaceans have elongated pincers, chunky claws, and a distinct tail, and they more closely resemble a lobster or a crayfish. The zoological treatise The Crustacea, published by Brill in 2004, states that, although crabs are the most frequent symbol of the Cancer sign, that the variety of shellfish that adorn horoscopes “can bring surprises” (Forest et al., 173). It is possible that while the symbol of Cancer may draw from a singular iconographic entity which included all shellfish, the idea of a distinct crab, including its spoken and written labels, could be historically transmutable. A definitive explanation for the choice of crustacean in horoscopes might be impossible, but there are some hints as to why “lobster-like” crabs were so pervasive in zodiacal art of the medieval period.

“Cancer,” “Crab,” & “Crayfish”

“Cancer” is an ancient word of Indo-European origin from a root meaning “to scratch.” Today Cancer is the scientific Latin genus name for “crab,” but in classical usage it described many species of shellfish. J.-Ö. Swahn notes in “The Cultural History of Crayfish” that in both Sanskrit and Greek the word for crab had the same meaning as crayfish, both animals having pincers. While the Latin word for Cancer, Carcinus, comes from the Greek karkinos, the English word “crab” has Germanic and Old English roots, and an Anglo-Saxon chronicle from about the year 1000 identified Cancer as crabba (Allen 107). In Old High German (800-1050), kerbiz meant simply “edible crustacean” and was also used to describe crayfish. The OED links the Middle High German (1050-1350) krebz to the Middle French (ca. 1400-1600) escrevisse, which in turn became écrevisse (crayfish).

The OED cites these words for crayfish, through much of their history, were general terms for all larger edible crustaceans. On “lobster,” OED notes some crayfish are called “fresh-water lobsters” and the term “lobster” is applied to several crustaceans of resemblance. Well into the seventeenth century, the word “cancer” and its translations were used as generic terms for all crabs and “lobster-like” creatures until Linnaeus established the species name Astacus Astacus for crayfish in his Systema Naturae of 1758 (interestingly, also with the synonym Cancer Astacus). The OED also noting that the 1656 translation of Comenius’ Latinae Linguae Janua Reserata, described the crayfish as a “shelled swimmer, with ten feet, and two claws: among which are huge Lobsters of three cubits; round Crabs; Craw-fish, little Lobsters.” So, etymologically speaking, crabs, crayfishes, and lobsters were mingled together from very early on.

Star Sign and Sustenance

In the Middle Ages, the zodiacal symbol of Cancer often appeared in the calendar pages of devotional books, or on adorned monumental sculpture of the Middle Ages. The Index records examples in these mediums (including examples on more than 200 manuscript pages) with the subject heading Zodiac Sign: Cancer. Generally, the depiction of the sign of Cancer as a crab is most prevalent in art from the Mediterranean and Western Europe, possibly due to the proximity to the sea, but the crayfish as a symbol for Cancer is not unusual, even in coastal regions. Crabs are saltwater decapods, creatures with ten feet or five pairs of legs. Crayfish are also decapods, but they thrive in freshwater lakes and rivers. Summer was the best season for fishing, and crayfish were easily trapped along the streams and creeks of rural Europe. The French and the English were the first to incorporate crayfish into their diet.

The Romans had viewed the crayfish as a scavenger animal, and they disliked the taste in their cuisine. Elevated from its lowly status as mere fodder in the classical era, crayfish came to be considered a delicacy in Western Europe from as early as the tenth century. In medicine, the sign ruled over the chest, stomach and ribs, and there are also several medieval pharmacological texts that note the medical properties of the crayfish, including the fact that “If you boil them in milk they cause a good sleep” (Swahn, “The Cultural History of Crayfish,” 247). We know that Europeans were using crayfish in their recipes and tinctures, so their distinctive form would have been a familiar one.

Sources

Allen, Richard Hinckley, Star-names and Their Meanings (New York, Leipzig: G.E. Stechert, 1899), 107-111.

Fischof, Iris, “The Twelve Signs,” in Written in the Stars: Art and Symbolism of the Zodiac (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 2001), 111.

Forest, Jacques, J. C. von Vaupel Klein, and J. Chaigneau, The Crustacea: Treatise on zoology – anatomy, taxonomy, biology: Revised and updated from the Traité de zoologie (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 173.

Larkin, Deirdre, “Making Hay: The Zodiacal Sign of Cancer,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Blog, June 5, 2009, http://blog.metmuseum.org/cloistersgardens/2009/06/05/making-hay/060509_bottom/

Swahn, J.-Ö, “The Cultural History of Crayfish,” Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture 372-373 (2004): 243-251.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Cancer,” “Crab,” “Crayfish,” “Lobster,” accessed June 2016, http://www.oed.com/.

“Summer and Crayfish,” The Medieval Histories Blog, June 15, 2016, http://www.medievalhistories.com/summer-and-crayfish/.

Reminiscences of Summer Holidays in France

To welcome summer, the Index of Christian Art presents an exhibit of travel ephemera from various cities in France. This selection of guidebooks and maps from the Index archive was inspired by a summer road trip to some of our favorite destinations, including Amiens, Tours, Bourges, Strasbourg, Beauvais, Dieppe, Toulouse, Chantilly, Beaune, Aigues-Morte, and NÎmes. Marked with the pencil signature of Rosalie Green, Index director from 1951 to 1982, many of these guidebooks and maps seem to have been used by Indexers researching cities with important monuments and museums relevant to the mission of the Index.

Guidebook of Chartres, “its Cathedral and Monuments,” by Alexandre Clerval (1859-1918) published in Chartres in 1926. Alexandre Clerval was a Chartrian priest who first wrote an important doctoral thesis on the School of Chartres in 1895.

Preserved in their original printed wrappers, these guidebooks provided details about places of interest to tourists and scholars alike. Perhaps Indexers used these very maps and books to plan an itinerary of sights and sites in all these cities. Mostly in French, and retaining period advertisements, the material here dates from the 1920s through 40s. The unfolded map of Strasbourg is from a Rapide-Plan printed by J. Finck in 1946. Although intended to accompany a traveler on the go, these pocket-sized guidebooks are also treasured by anyone who enjoys armchair travel to distant shores or a lazy summer day lost in remembrance of things past.

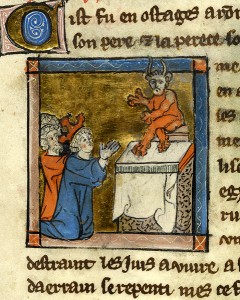

Detail of Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent. Old Testament Picture Book. French, c. 1250. Morgan Library, M.638, fol. 8r

Nine times Moses went to the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II to demand freedom for the Israelites in captivity, saying “Let my people go.” Each time Moses and his brother Aaron were sent a way, an episode classified by the Index as, Moses and Aaron: driven from Pharaoh’s Presence. Despite these increasingly tense exchanges, and then a marvelous act that changed Aaron’s rod into a serpent before the Pharaoh’s court (Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent), Ramses still refused to release the Israelites from slavery.

What followed was the foretold wrath of God enacted as ten crippling plagues on the Egyptians. In the first wave of calamities, there were plagues of blood, frogs, gnats, and lice that polluted the air and water. The second wave, brought plagues of flies, diseased livestock, and boils. Then came hail, locusts, and darkness that fell on Egypt for three days. The tenth and final plague, the “Plague of the Firstborn,” claimed the lives of the eldest children in all Egyptian families. The Index of Christian Art classifies the subjects of the Exodus plagues under the major figure of Moses:

Moses: Plagues of Flies, Frogs, Locusts, Hail and Pestilence. Stuttgart Psalter, c. 820-830. Stuttgart Landesbibliothek, Bibl.fol.23, fol. 93r. Photograph by Gabriel Millet.

(Exodus 9:6-7)

The final plague is described in several phases throughout the books of Exodus (11:4-8; 12:1-13, 21-23, 29-30). Moses first warns of its coming to the embattled Ramses, but his warning is dismissed.

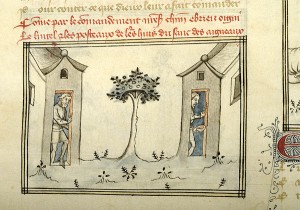

Facing the impending deadly plague, Moses instructs the Israelites to make a sacrificial offering to God, and to use the blood of the animal – a male yearling – to mark the doorposts and lintels of their homes. Moses explains to them that marking their homes this way will spare their firstborn children from the “death angel,” saying he “will pass over the door.” (Exodus 12:23).

Moses: Plague of Firstborn. Two Israelites marking the doorposts and lintels of their homes with the blood of the sacrificial lamb. History Bible, Paris, c. 1390. Morgan Library, M.526, fol. 14v

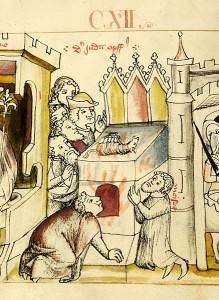

Detail of Moses: Passover. Israelites cooking the sacrificial lamb under the inscription “Die Juden Opffer.” Historien Bibel, Swabia, late 14c. Morgan Library, M.268, fol. 7v

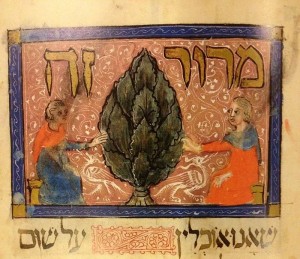

Following this, the Israelites were delivered from bondage and departed from Egypt. The Exodus is remembered at the feast of Passover – the Hebrew feast of Pesach – with special instructions for preparing, eating, and storing traditional, often symbolic food. While Passover traditions have varied over time and from one region to another, it is generally a family holiday in which the meal is accompanied by readings, songs, and traditional rituals designed to remind the celebrants of the Exodus story and the hopes for a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. The order of the seder, or Passover meal, is set out in a book known as the Haggadah, which was sometimes richly illuminated in the Middle Ages, as shown here in the Sarajevo Haggadah, originating in Barcelona in the middle of the 14th century. Well-known related manuscripts to this Haggadah include the Rylands Haggadah and the Simeon Haggadah. The Index classifies subjects depicting the original Passover feast as Moses: Passover, Moses: Passover proclaimed, and Moses: Law, Feast of Passover and with a general heading for Scene: Passover.

Bitter herb or “maror” in the Sarajevo Haggadah. Barcelona, c. 1350. Sarajevo, National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photograph Wikimedia Commons.

Words and Deeds of Charles Rufus Morey at the American Embassy in Rome (1945-1950)

Charles Rufus Morey, founder of the Index of Christian Art, was the first to fulfill the role of American cultural attaché to Italy, a tenure beginning with his retirement from Princeton University’s Department of Art and Archaeology in 1945. A champion of Italian culture, Morey’s mission at the American Embassy in Rome not only promoted Italian national heritage but reconstructed it after the ravages of world war. Morey’s distinguished background in classics and art history, coupled with his longstanding ties to the study of historical Rome, made his assignment all the more fitting.

As a diplomat, Morey actively sought opportunities to repatriate books and works of art looted in wartime Europe and he created the Union of Archaeological and Historical Institutes to safeguard artifacts in transit. Two of his notable publications while in Rome were, “The War and Medieval Art,” College Art Journal, IV, 1945, and “Saving Europe’s Art,” Journal of the American Institute of Architects, III, 1945. Among his main activities were the establishment and maintenance of research libraries in Italy. Morey oversaw the direction of the American Academy in Rome from 1945 to 1947, where he brought in major speakers, lectured widely, and organized exhibitions which increased Italian–American cultural exchange. He formed many collegial relationships with important people, among them nobles, curators, and clerics, who knew him as Professore. Pictured here from the Index archive is a photographic postcard dated 1948 of Morey with Prince Don Giovanni Francesco Alliata di Montereale, President of the Nato-American Association, while they walk together in Segesta, Sicily.

The Index is fortunate to house a wealth of materials associated with Morey during his time in the Foreign Service. Through these items, we wish to show a different facet of the founder of the Index, whose words and deeds as a cultural attaché to Italy left a lasting mark on this organization. On long-term display in the Index is a collection of Morey’s prize medals given to him on various occasions, including one from Pope Pius XII to commemorate the Jubilee year in 1950.

This exhibition was planned to accompany the 25-26 March 2016 Symposium of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence, “Words and Deeds: Actions Enacted, Re-Enacted & Restored.” These materials will be on view until 31 May 2016.

The model during Lent, the forty days of reflection and restraint before Easter, is Christ in the desert overcoming temptation. According to the Gospel writers Matthew, Mark, and Luke, Christ wandered alone in the Judean desert for forty days immediately following his baptism and before starting his public ministry. Satan first tempted Christ in the desert to turn stones into bread. Christ responded by quoting Deuteronomy 8:3, “It is written, man shall not live by bread alone…”. The Gospels describe two other attempts of temptation to win over both Christ’s pride and power. On the second temptation and with a dramatic setting change, Satan tested Christ to act independently from God and use his divine powers to jump from the height of the temple in Jerusalem – Christ firmly refused. Finally, Satan made a grand offer to Christ; to bask in the glory of all the kingdoms of the world if he would give up his mission and be partners with Satan, to which Christ replied, “Get thee hence.”

By the time of Gregory the Great, Pope from 590-604 CE, medieval Christians were expected to observe Lent by emulating these desert trials of Christ by fasting from animal products, remaining diligent in prayer, and giving alms to the poor. Typically, one meal per day was consumed during Lent; save the worship day of Sunday, observers were to resist all carnal attractions. The strict prohibitions during Lent required endurance from believers and tested their own degree of devotion.

The Index classifies the Temptation episodes in three major divisions according to the number of times the devil tried to seduce Christ. Currently, the database records the most scenes for “Christ: Temptation, 1st,” the temptation for hunger, and works of art are mostly executed in manuscript illumination, but also stained glass, fresco, and sculpture, as shown. There is also a general subject category for “Christ: Temptation” which is used to describe scenes where Christ and Satan are facing each other in an unknown part of the narrative or when all three Temptations are depicted in one scene as in the south vault mosaic at San Marco in Venice . “Christ: in Wilderness” is often a subsequent subject heading applied to the Temptation scenes as well as, “Christ: ministered to by Angels.” The latter records a specific part in the narrative when Christ is kept alive in the desert by angels following the departure of the devil. Lent, coming from the Old English word “lengthening,” is the transitional time in the church calendar and for the seasons.

Places of Power

The Index of Christian Art announces an exhibition of rare photographs of important monumental sculpture entitled Places of Power. On display will be a selection of photographs of significant places in major European cities, including two pre-1900 views of L’Arc de Triomphe and the façade of the Pavillon Sully wing of the Louvre Museum in Paris, a rare image of the piazza del duomo in Milan taken before 1896, twenty postcard views of Strasbourg Cathedral dating to the 1920s, and a large mounted study photograph of the twelfth-century Last Judgment scene on the tympanum of St. Foy at Conques, France, a key stop for pilgrims traveling to Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain.

The photographs will be on display through March as part of the Index’s rotating exhibition program.

Hanukkah, the Feast of Dedication, also called “Festival of Lights,” commenced yesterday (December 6th) at sundown and will continue for eight days. Hanukkah was celebrated as early as the second century BCE to commemorate the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Under Greek imperial rule, many key Jewish practices had been outlawed and the Temple in Jerusalem was filled with pagan implements. The Hellenization of Jerusalem brought with it the dedication of the Temple to Zeus, the destruction of Holy Scriptures, and many crippling assaults against Jewish custom. The Book of Maccabees recounts the story of Judas Maccabeus, son of the priest Mattathias, and his brothers, who formed a revolt against the Seleucid Empire of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, eventually winning against his heir and successor Antiochus V (See I Maccabees 6). A series of battles ensued from 167 to 160 BCE to reclaim Jewish heritage and freedom to worship in the Temple.

The pinnacle win is classified in the Index under the subject heading, “Maccabees: Battle against Antiochus V” and covers thirteen works of art in the database, mostly in manuscript. Several siege scenes of the Maccabees against Antiochus V armies feature the “Animal: Elephant and Castle” iconography based on the passage in I Maccabees chapter 6. In the passage, Eleazar Avaran runs toward the elephant in royal armor which he believes might harbor the king. In a twist of fate, Eleazar stabs the elephant and it tramples and kills him. Other key Index subjects relating to the history of Hanukkah include, “Antiochus IV: Siege of Jerusalem,” “Antiochus IV: Pollution of Temple,” “Judas Maccabaeus: Cleansing of Sanctuary,” and “Judas Maccabaeus: Altar rededicated.” After the Jews reclaimed the Temple in Jerusalem, it was purified and reconsecrated by the lighting of a multi-branched oil lamp which miraculously burned for eight days; an event which would be marked with the celebration that we now know as Hanukkah.

In medieval times, the growing custom of illuminating the menorah lamp, usually displayed outwardly, fulfilled the rabbi’s decree to confirm the “miracle of lights” to the world. The Index classifies menorah imagery under the subject heading “Candelabrum,” using the keyword “menorah” in a description field. There are 177 database examples in a variety of media including stained glass, sculpture, mosaic, terra cotta, and manuscript illumination.