Shepherd at the Nativity. Fourth century sarcophagus. Arles, Musée de l’Arles et de la Provence Antique, FAN.92.00.2517. Index system number 000107697.

Of all the medieval images associated with the Christmas story, surely most familiar is that of the Nativity, which depicts the Christ child in the lowly stable of his birth, almost always attended by the Virgin Mary, her husband Joseph, and the ubiquitous ox and ass. Medieval nativity scenes often included other onlookers as well, from the shepherds and magi to whom angels announced Jesus’ birth to the midwives who, in some accounts, assisted at it. Of all these figures, few have a longer or more engaging history than the shepherds, with whose homespun character and simple faith many ordinary medieval Christians could identify.

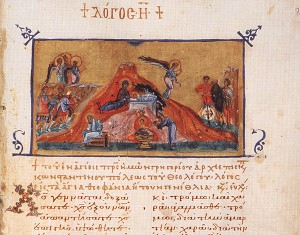

Shepherds and Magi at the Nativity. Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen, 11th century. Jerusalem: Greek Patriarchal Library, MS Taphou 14, fol. 80r. Index system number 150818

The shepherds themselves have biblical origins: Luke 2:8-20 describes them receiving news of Christ’s birth from a host of angels, then rushing to the stable to see the child for themselves. The scene of the angelic annunciation to the shepherds is sometimes presented adjacent to or in the background of the Nativity, and in the very late Middle Ages, under the influence of Franciscan piety, it was also depicted as an independent scene. However, from the beginnings of Christian art, the shepherds were also frequent onlookers at the Nativity itself. By the fourth century, Roman and Gallic sarcophagi had begun to include one or two shepherds standing beside the manger, often raising a hand in recognition of Jesus’ divinity; middle Byzantine mosaics often cast the shepherds as a trio to balance the three magi who also attended the child. Such pairings were encouraged by medieval texts that presented the shepherds as symbolizing the Jewish tradition from which Christianity had sprung and the magi as representing those pagans who converted to the faith. Alternatively, the magi and shepherds were sometimes presented as demonstrating Christ’s recognition by all walks of life, a universalistic message sometimes developed further in the portrayal of both groups as men of varying ages and even ethnicities.

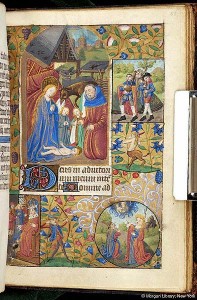

Music-making shepherds on the margin of the Nativity, ca. 1470. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS m.32 fol. 51r, Index system number 000175635

Late medieval pietistic trends, which promoted the idea that the poorest of men had been the first to receive news of Christ’s birth as confirmation of the value of humility and simplicity, encouraged fourteenth- and fifteenth-century artists to elaborate their images of the shepherds. They often are shown as rough-hewn peasant types—sometimes even including a shepherdess—who offer the child simple, heartfelt gifts, such as a lamb, a flute, flowers or, more unusually, a basket of eggs. The appeal of these humane, familiar figures still resonates in many a Christmas sermon as well as Christmas carols, from the traditional Austrian “Shepherd’s Carol” to the 1941 pop hit “The Little Drummer Boy.”

Shepherds are noted in over 650 records of the Nativity in the online database of the Index of Christian Art; many more can be found in the card files. Media include sculpture, gold glass, manuscripts, enamel, mosaic, fresco, and painting. We wish all our friends who celebrate Christmas a joyous and peaceful holiday.

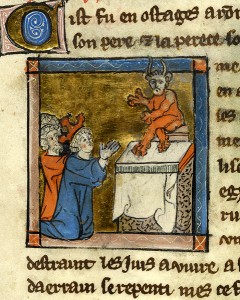

Hanukkah, the Feast of Dedication, also called “Festival of Lights,” commenced yesterday (December 6th) at sundown and will continue for eight days. Hanukkah was celebrated as early as the second century BCE to commemorate the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Under Greek imperial rule, many key Jewish practices had been outlawed and the Temple in Jerusalem was filled with pagan implements. The Hellenization of Jerusalem brought with it the dedication of the Temple to Zeus, the destruction of Holy Scriptures, and many crippling assaults against Jewish custom. The Book of Maccabees recounts the story of Judas Maccabeus, son of the priest Mattathias, and his brothers, who formed a revolt against the Seleucid Empire of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, eventually winning against his heir and successor Antiochus V (See I Maccabees 6). A series of battles ensued from 167 to 160 BCE to reclaim Jewish heritage and freedom to worship in the Temple.

The pinnacle win is classified in the Index under the subject heading, “Maccabees: Battle against Antiochus V” and covers thirteen works of art in the database, mostly in manuscript. Several siege scenes of the Maccabees against Antiochus V armies feature the “Animal: Elephant and Castle” iconography based on the passage in I Maccabees chapter 6. In the passage, Eleazar Avaran runs toward the elephant in royal armor which he believes might harbor the king. In a twist of fate, Eleazar stabs the elephant and it tramples and kills him. Other key Index subjects relating to the history of Hanukkah include, “Antiochus IV: Siege of Jerusalem,” “Antiochus IV: Pollution of Temple,” “Judas Maccabaeus: Cleansing of Sanctuary,” and “Judas Maccabaeus: Altar rededicated.” After the Jews reclaimed the Temple in Jerusalem, it was purified and reconsecrated by the lighting of a multi-branched oil lamp which miraculously burned for eight days; an event which would be marked with the celebration that we now know as Hanukkah.

In medieval times, the growing custom of illuminating the menorah lamp, usually displayed outwardly, fulfilled the rabbi’s decree to confirm the “miracle of lights” to the world. The Index classifies menorah imagery under the subject heading “Candelabrum,” using the keyword “menorah” in a description field. There are 177 database examples in a variety of media including stained glass, sculpture, mosaic, terra cotta, and manuscript illumination.

Photo: The Aberdeen Bestiary Website (https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/comment/81risidf.hti; consulted 12/4/15)

Welcome to the new website of the Index of Christian Art. Our updated and more user-friendly design preserves many of the things researchers have counted on finding here: information about our history, holdings, and hours; additional image resources; news about events and publications, including the annual journal Studies in Iconography; and a link to our online database. However, it now also includes updated information about our staff and their projects, new information about our resources and services, and periodic blog posts on topics of interest to a range of medievalist researchers.

Our website redesign, created by our Technology Manager Jon Niola with content input from several of our research staff, represents only one of several initiatives under way at the Index this year. The most important to external researchers will be a total revamp of our venerable online database to allow for a friendlier design, more flexible, intuitive searches, and easier access to information and images. We hope to put this into place in time for the Index’s centennial in 2017. Other initiatives include the inauguration of Index Workshops, in which faculty and students in the department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton can join with Index and area scholars to workshop papers and publications in progress, and the revival of the well-known Index Conference Series, which reboots on April 29 with a one-day conference titled “Plus Ça Change? The Lives and Afterlives of Medieval Iconography.”

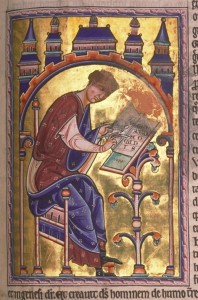

We would like to think that our technological updates would please St. Isidore of Seville (ca. 560-636), who in 1997 was nominated by Pope John Paul II to become patron saint of the Internet. Bishop of Seville for over thirty years, the learned Isidore richly deserves the honor: his most famous work, the 20-volume Etymologiae, attempted to summarize all human knowledge in the manner of Classical scholars. Its scope ranges from theology and the liberal arts to medicine, animals, and daily life, offering the reader a plethora of surprising and sometimes colorful details about such topics as the causes of an eclipse, the behavior of ants, and the names of various women’s garments. Its wide use and continued importance throughout the Middle Ages can be judged by its countless citations (dare we call them re-tweets?) in works by medieval authors, including such luminaries as Dante, Chaucer, Bocaccio, and Petrarch. Isidore of Seville is represented by 28 records in the Index, both in the database and physical card file; he is often shown writing busily at a lectern, as in the late twelfth-century Aberdeen Bestiary (Aberdeen University Library, MS. 24, fol. 81r). Further subject references to Isidore can be found under, “Clergy, Bishop: Isidore of Seville” and “Scribe, Male: Isidore of Seville.”