This summer The Index of Medieval Art welcomed two students from the Master of Information program at Rutgers University to inventory the Index’s photographic archive. Comprising nearly two hundred thousand cards in sixteen different medium categories, this historic image collection provides researchers a rich resource of sometimes rare visual references for the study of art produced throughout the Middle Ages. The inventories undertaken by Ryan Gerber and Michele Mesi have illuminated the extent of the archive and helped to assess the image and cataloguing needs for ongoing research and cataloguing at the Index. In this special two-part blog post, we are pleased to present their observations and accounts of their experiences.

It is a testament to the Index’s stimulating power that, despite my lack of an art-historical background, I found myself entranced by the system of cataloguing medieval iconography that the Index pioneered and is still practicing to this day. Its vision of greater accessibility through complete digitization represents another milestone in its long history, and one which will be a gift to scholars of all persuasions and experience levels.

A system largely developed by Index director Helen Woodruff in the 1930s, the photographic archive is organized in the first place by medium, then by location, object type, and the numeric order within that group. Unique codes on the left-hand corner of every index card in the catalogue represent each of these levels of organization. The fruits of this labor are hard to miss after spending any time with the Index and its elegantly interwoven subject index and photographic archive, where one can move seamlessly from subject description to pictorial representations and vice versa.

This work has also left behind a trove of archival resources such as hundreds of rolls of film and the so-called “Black Books” that were used to track the negative numbers. Each of the medium categories I inventoried not only laid the groundwork for further analysis of the collection as a whole, but highlighted the Index’s remarkable century-old ability to generate new curiosities and paths of inquiry.

Terracotta, Temporary Cards, Lamps, and Lions

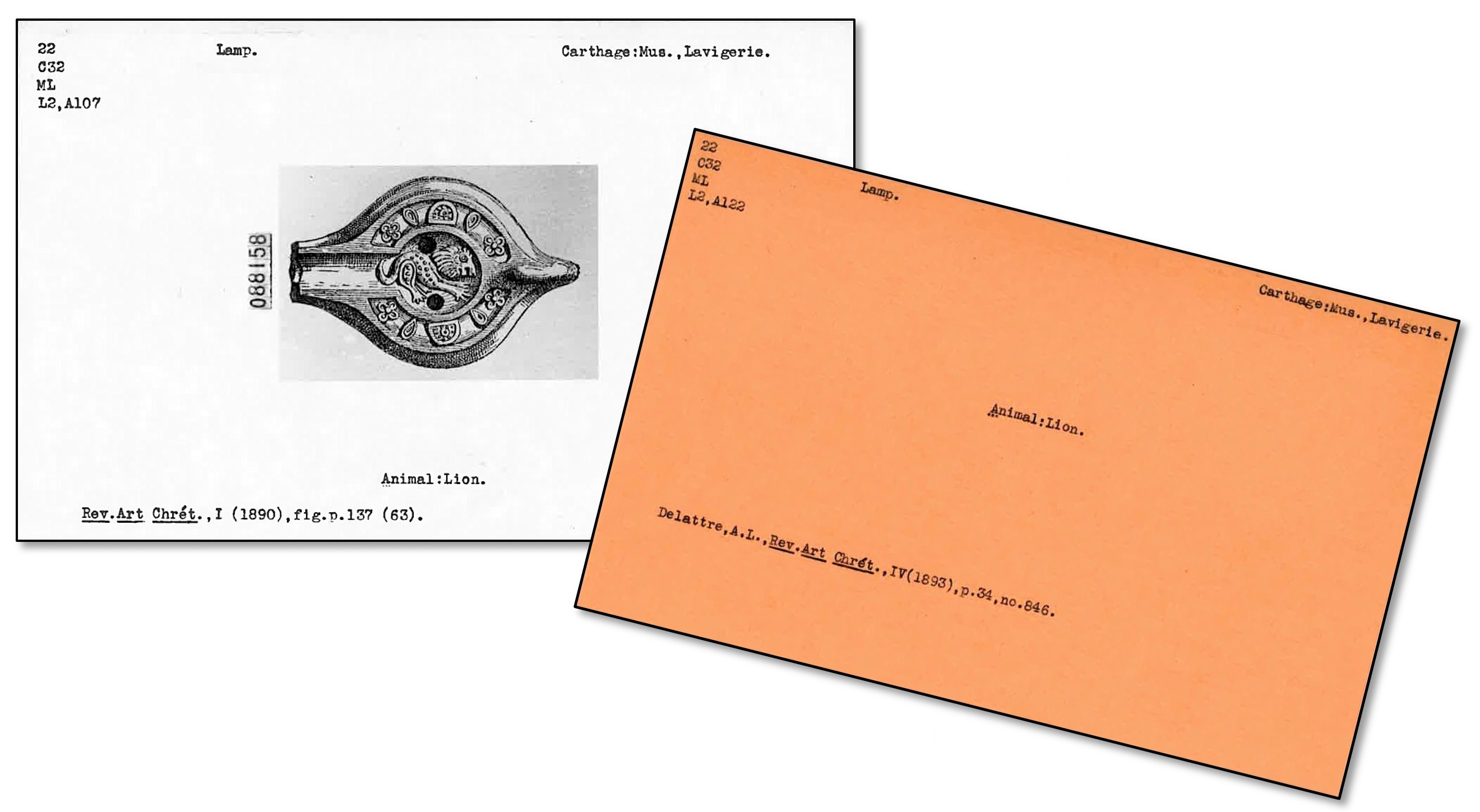

Under the medium “Terra Cotta”—a mixture of clay and water that is formed and baked or fired—the Index records more than twenty-five hundred objects across 196 locations. Of these objects, about sixty-five percent of them are oil lamps. The inventory of these files revealed some of the more common iconographic motifs found on terracotta objects, which include foliate ornament, a variety of land animals and birds, symbols such as crosses, as well as inscriptions and monograms. One terracotta lamp from the Benaki Museum in Athens depicts two of these popular motifs—a lion and a tree—combined on one impressed discus (Fig. 1).

Most photograph cards contain representations of the objects, but they also record the object’s location, the photograph’s negative numbers, subject headings for the image or images on the object, and some bibliographic information. However, there are many temporary “Orange Cards” in the archive that contain only a bibliographic reference and a subject term, and these still await corresponding images. Their inclusion in the original system nonetheless provides important data points about the objects they describe, laying the groundwork for future cataloguers to source the images for these object records. For example, the Index’s photo archive of terracotta objects in the National Museum at Carthage is mostly Orange Cards because the original Index records of these objects derive from a 19th-century publication with very few illustrations. While it would be useful to see images of the “lions” held at the National Museum in Carthage, even in the absence of photographs it may be just as useful to know that, of the 970 terracotta lamps held in that location, nearly four hundred depict animals, and about sixty-five of those include a lion.

A Face in Gold Glass

The “Gold Glass” files record over 650 objects across sixty-three locations dating mostly from late antiquity between the 3rd and 7th centuries. Of these objects, nearly half are vessels of some kind. Gold glass developed as a medium in the ancient Roman and Hellenistic periods and consisted of decorative engravings made in gold leaf, which were then sandwiched between fused layers of glass. The result was lavish decoration, and exemplary pieces in this medium offer strikingly detailed portraits of their subjects, often depicting married pairs, family groups, or religious figures associated with one another, such as Saints Peter and Paul. Historians have noted the rarity of gold glass, as well as its costly, specialized method of production.[1]

Gold glass was a special interest of Index founder Charles Rufus Morey, and his pioneering catalogue of the Vatican Library’s collections features as its first entry an example also catalogued by the Index. It shows the busts of a married couple inscribed above with the name Gregori and a Latin equivalent of “cheers!”: “Gregori bibe [e]t propina tuis,” or “Gregory, drink and drink to thine!” (Fig. 2).[2]

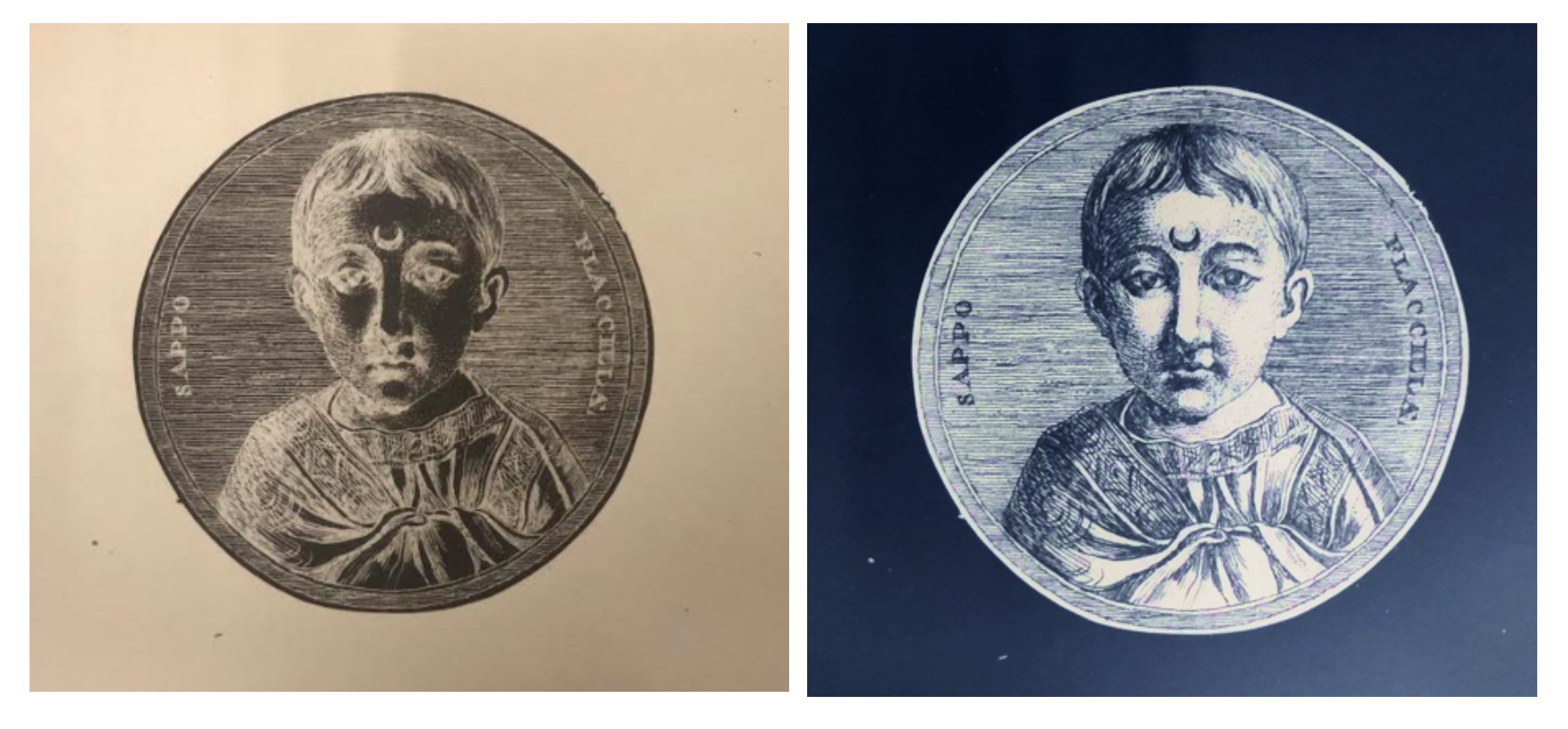

Another interesting discovery in the “Gold Glass” category was a round vessel fragment last recorded in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris. It depicts a striking bust of a figure with shorn hair, dressed in a trimmed tunic, and with a distinctive crescent shape on their forehead. The only other information on the photograph card was the source of the image, the antiquities catalogue that Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus published in seven volumes from 1756 to 1767.[3] Caylus’s catalogue was a valuable starting point for identifying this figure, whose iconographic description had not been entered in the Index’s subject files or the database. A little more searching led to a color image in a French catalogue, the Histoire de l’art de la Verrerie dans l’Antiquité (Fig. 3), and to the conclusion that the inscription “SAPPO FLACILLAE”—with the genitive form of the empress’s name—referred to a branded enslaved person who had been freed by the Roman Empress Aelia Flacilla (356–386). We also used the photo-editing web application Pixlr to create a positive image of “Sappo” so that the image from the Index archive can now be seen as it appeared in the catalogue of the comte de Caylus (Fig. 4).

Impressions in Wax

Comprising a little over one thousand objects in 105 locations, the “Wax” medium files are overwhelmingly made up of stamps from Europe dating largely to the 13th and 14th centuries. Although the archive groups these objects into the single object category “Stamp,” the Index database divides them into two Work of Art Types, “Seal Matrix” (that is, the tool used to make the impression) and “Seal Impression” (that is, an impression made by a matrix).[4] Viewing about a thousand examples of Gothic seals intended for both religious and secular officialdom brought into literal relief the development of the production of seal dies from simple figural representations to complex ecclesiastical chapters in miniature, such as the Stamp of Ely Priory, dated to about 1240–1260 (Fig. 5). Other favored subjects in wax seals include heraldry, nobles, and popular saints and bishops, like Thomas Becket. The wealth of iconographic information in the “Wax” files—indeed throughout the archive—emphasizes that the Index is not a closed system, and has at every turn great potential for leading one into new areas of inquiry.

Ryan Gerber is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. He holds an MA in English from The College of New Jersey with a concentration in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. His interests include digital preservation and retrieval, the digital humanities, and information behavior.

See Part 2 written by Michele Mesi.

[1] Giulia Cesarin, “Gold-Glasses: From their Origin to Late Antiquity in the Mediterranean,” in Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millennium AD (London: UCL Press, 2018), 22–45.

[2] Morey noted of the inscription that “the E of ‘bibe’ or of ‘et’ [was] omitted by mistake.” Charles Rufus Morey, The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1959), 1. Translation after Georg Daltrop in Leonard von Matt, Georg Daltrop, and Adriano Prandi, Art Treasures of the Vatican Library (New York: Abrams, [1970]), 168.

[3] Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus, Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, greques, romaines et gauloises (Paris, 1756–57), 193–205, pl. 53.2, https://archive.org/details/recueildantiquit03cayl/page/n10.

[4] See the Index database Work of Art Type browse list to access these Work of Art References.

Precious Gems Containing a Wealth of Iconography

“Glyptic” is among the smaller medium categories in the Index archive, filling only one drawer with a little more than eleven hundred cards that record only about nine hundred objects. The term “glyptics” refers the art of carving gems or seals—whether in intaglio or in relief—typically in gems or precious stones such as jasper, agate, carnelian, and amethyst.[1] This form of art is one of the oldest—known since the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Assyrian civilizations—but it was not until the Hellenistic period that relief cameos, seals, and more intricate glyptic objects began to appear.[2]

Glyptics, which were often worn as jewelry or incorporated into ecclesiastical objects, are recorded in the Index primarily as gems, amulets, plaques, rings, and stamps, and the largest category, cameos, which makes up nearly a third of the glyptic objects in the Index files. A significant portion of the subjects on these carved gems include animals and plant life, like doves, dolphins, fish, palm trees, and fantastic creatures. There are other symbols as well, such as the anchor, which appears on over forty examples. A significant number of glyptics incorporate classical and mythological figures, such as Orpheus, Diana, Jupiter, and Hecate. Nearly twenty cards for gem objects record the Gnostic figure Abrasax (Fig. 1). Glyptics such as these were powerful talismans for their owners.

The traditional use of spiritual amulets was also adopted by Christians using Christian symbols and themes.[3] Christian iconography on glyptics include the triumphant Archangel Michael or Saint George, Daniel in the Lion’s Den, and the Good Shepherd. One cameo of opaque black glass made in the 13th century depicts Saint Theodore transfixing the dragon and well represents the preference for saintly imagery on later cameos (Fig. 2).[4] The inventory also revealed that there were nearly thirty examples of incised depictions of monograms on glyptics with a third of them being the Chi-Rho, a symbol for Christ consisting of the first two letters of the word “Christos” (Christ) in Greek.

The major collections represented in this medium include the Staatliche Museen in Berlin (over eighty objects) and the British Museum in London (nearly 125 objects. However, a large number of glyptics (over 140 objects) are recorded as “Location Unknown,” these items having been entered into the Index from major publications that did not provide the precise location at the time of publication.

Radiant Ivories for Both Secular and Religious Narratives

With nearly forty-seven hundred cards covering a little over thirty-one hundred objects, Ivory represented a more extensive category in this inventory project. The types of ivory objects recorded by the Index range from plaques, chess pieces, croziers, and triptychs to the more unusual oliphant (or hunter’s horn) to the handles of various utensils, and even a saddle. Some of the major collections represented in this medium are the Musée du Louvre and the Musée de Cluny in Paris, and the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Ivory objects were expertly carved in minute detail, usually from the tusks of elephants. In the Index database, ivory acts as a “parent medium,” an umbrella covering such materials as bone, walrus tusks, and antlers.[5]

Various motifs of courtly love were often depicted on ivory caskets, plaques, mirror cases, combs, and other fine domestic objects.[6] A preference for secular subjects on ivories emerged in the twelfth century when an influx of secular imagery was brought to Europe from the Middle East after the Crusades, as well as through a rise in vernacular literature, legends, and romances.[7] Entertaining stories such as the tale of the Virgin and the Unicorn provided plenty of thematic material to adorn precious ivory objects. They often offered a double meaning or moral lesson, as in the story of Tristan and Isolde depicted on an early 14th-century ivory casket now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which warns against temptations of lust (Fig. 3).[8]

Despite their popularity, secular ivories are fewer in number than devotional works of art in ivory. Roughly a quarter of the ivory objects recorded in the Index are representations of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. This figure rises to more three quarters when we add individual figures of Christ or the Virgin Mary. One type seen rather frequently is that of the Virgin nursing the infant Christ—known in Latin as the Virgo Lactans—which the Index categorizes among the many “types” of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. In the database, the subject heading Virgin Mary and Christ Child, Suckling Type is attached to over 290 Work of Art records. More than forty of these are ivory. This Virgo Lactans iconographic type is exemplified by a 14th-century ivory statuette in the Yale University Art Gallery, which displays an intimate and lifelike relationship between mother and child (Fig. 4). Thus, the devotional message is made personal.

The Project Continues …

Encompassing eight drawers of roughly one thousand cards each, “Painting” proved to be an abundant medium, but “Illuminated Manuscript” is by far the largest medium category in the Index, filling fifty-six of the photograph drawers. Medieval art objects encountered in these two categories range from painted icons and altarpieces to a wide variety of liturgical manuscripts and other illuminated books numbering perhaps in the thousands. The inventory of these and other remaining categories—including those comprising in situ works of monumental art, such as “Mosaic” and “Fresco”—will continue after this summer.

As a “living archive” that covers more than a millennium of artistic creation, the Index of Medieval Art has always been improved and expanded by the interactions of the cataloguers who create it with the with researchers who use it. Creating these inventories has been an illuminating way to participate in that process and to learn more about the contents of the Index card catalogue being prepared for entry into the online database. This project was challenging at times, due to the sheer breadth of the paper files, but it has been an invaluable undertaking for the ongoing process of research and digitization, and will improve accessibility to the records contained in this century-old archive of medieval art.

Michele Mesi is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. From Rutgers University, she also holds a Bachelor’s degree in English with studies in Art History and in Digital Communication, Information, and Media. Her interests include art conservation, archival processing, and working with rare books and manuscripts.

See Part 1 written by Ryan Gerber.

[1] The Index of Medieval Art follows the standards for material description established by the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). See the Art & Architecture Thesaurus® Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/.

[2] O. Neverov and A. Durandin, Antique Intaglios in the Hermitage Collection (Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1976), 7.

[3] Neverov and Durandin, Antique Intaglios, 8.

[4] The Index records the iconography in question as Theodore Tyro or Theodore the General, Slaying Dragon.

[5] See the glossary entry on the Index database Medium browse list for “ivory.”

[6] J. Lowden and J. Cherry, Medieval Ivories and Works of Art: The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario (Art Gallery of Ontario, 2008), 122.

[7] R. H. Randall, “Popular Romances Carved in Ivory,” in Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age (Detroit Institute of the Arts, 1997), 63.

[8] Randall, “Popular Romances,” 67–68.