Observing the passing of time was central in medieval society, since climate had a profound effect on one’s livelihood and life habits. The turn of the seasons brought changes in diet, hygiene, mood, and activity, which were detailed and collected in a genre of late medieval health handbook known as Tacuinum Sanitatis (“The Maintenance of Health”). These show that, in preparing treatments, doctors took the time of the year, month and even day into account, along with six ‘non-natural’ factors—air, food and drink, motion and rest, sleep and waking, secretion and excretion, and mental state—as well as bathing (Jones 119; 133). Such factors are reflected in the Psalter of Lambert le Bèque, which includes twelve medallions forming a health calendar with rules and advice for each month and an image of a doctor with his assistants at the bottom of the page.

While elements of the illustrations were drawn from classical tradition, the medical recommendations and notion of time in the Tacuinum Sanitatis were heavily influenced by similar health handbooks in Arabic, the lingua franca of the Islamic world. The Tacuinum Sanitatis was based on an Arabic text written by Ibn Butlan, an eleventh-century Christian physician from Baghdad, who is credited as a source in manuscripts from Vienna, Paris, Casanatense, and Liège. His work was so respected by European translators that they even copied out mistakes made by previous Arabic copyists without change. Its translation into Latin in southern Italy or Sicily helped to disseminate it across Europe (Arano 8–11). The work’s Arabic origins are reflected in the title Tacuinum, which comes from the Arabic taqwim, meaning “table” and referring to the table-like organization of health handbooks in the Arabic tradition, a configuration possibly referenced in the square shape of the illustrations in the Tacuinum Sanitatis.

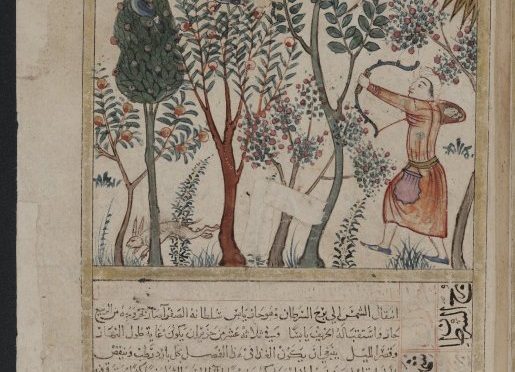

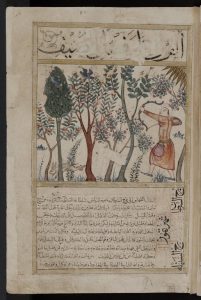

A sense of the Arabic source for the Tacuinum Sanitatis can be found in the Kitab al-Bulhān, a fifteenth-century miscellany in Arabic, now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (MS. Bodl. Or. 133). The Bodleian manuscript compiled various astrological, astronomical, and divinatory texts. Notably, in its tale for the four seasons, it advised the following diet for the summer months:

“Food should be reduced and drink somewhat increased. Drinks must be well mixed with cold water and snow. Warm, dry medicines and foods must be avoided. Only delicate meat is to be eaten, such as that of black lamb (al-humldn al-suid). There is no harm in eating beef and goat’s meat if prepared with vinegar and celery (karafs). One should not linger in the bath nor should emetics be resorted to frequently.” (Arano color plate XII).

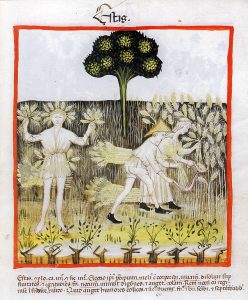

Similar instructions for a humid diet and delicate foods that can be easily digested also appear in a fourteenth-century Latin manuscript of the Tacuinum Sanitatis, written in Lombardy and held in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Cod. Vindob. ser. nov. 2644, fol. 54r). This manuscript states that when nature is “warm in the third degree, dry in the second” the body is at its optimum health to beat “superfluities and cold diseases.”(Arano color plate XII). Yet the summer months were not without their health afflictions, like sluggish digestion or an increase in bilious humors. The Vienna Tacuinum codex suggests taking in a “humid diet” in a “cool environment” to overcome these disagreeable humors. The handbook states that a continuation of the diet works in “cold temperaments, for old people, and in Northern regions.” (Arano color plate XII).

The accompanying image of a youth wearing a crown of grain and holding a sprig is strikingly similar to depictions of the labors of the month and the personification of summer.

This imagery found its way into other media recorded by the Index, such as a Veronese fresco fragment in the Museo Civico di Castelvecchio in Verona. Dated to the last quarter of the fourteenth century, this fresco contains three scenes from the Tacuinum Sanitas. Fragments from the Palazzo dei Tribunali in Verona depict occupational scenes of cooking and commerce that address the inclusion of starch and dill in the diet.

Interestingly, once the Tacuinum text became popular in Europe, Italian innovations began making their way back into Arabic manuscripts. The illumination in the Lombardy manuscript was also influential in the development of contemporary landscape painting, focusing on the changes in nature itself, as well as human responses to them. This influence is perceptible in the Bodleian manuscript, made approximately a decade after the Italian manuscript. The illumination of seasons and cycles here shows a distinctly European approach with Arabic elements worked in. These details include turbaned figures in rich pastoral landscapes dotted with European architecture, a hunter’s long, pointed shoes, a half-length traditional gown, a belted pouch and a goblet of wine in the Autumn scene. And so the artist of the Bodleian Kitab al-Bulhān blended elements of both cultures with innovations of his own, according to his taste.

The Index catalogs many images of seasonal and medical imagery, including “Scene, Occupational: Doctoring” (60+ work of art records) and “Scene, Occupational: Cooking” (70+ work of art records).

Sources:

Ann Henisch, Bridget. The Medieval Calendar Year. (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1999)

Carson Webster, James.The Labors of the Months in Antique and Medieval Art to the End of the Twelfth Century. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1938)

Cogliati Arano, Luisa. Medieval Health Handbook: Tacuinum Sanitatis. (New York: George Brazilier, 1976)

Hourihane, Colum, ed. Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months and Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art. (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2007)

Murray Jones, Peter. Medieval Medical Manuscripts. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984)

Rice, D. S. ‘The Seasons and the Labors of the Months in Islamic Art’. Ars Orientalis 1 (1954): 1-39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4628981.pdf

This guest blog post was written by Rachel Dutaud, a summer student assistant at the Index of Christian Art and a fourth year art history student at the University of St. Andrews. Rachel is completing her undergraduate dissertation on the portraiture of Hatshepsut, Olympias of Macedonia, and Theodora. Her interests are in Early Christian and Byzantine art, classicism, iconography, and archives.