Going to Kalamazoo this year? Ever wanted to learn more about the impact of digital tools and methods on medieval art research? Be sure to circle your programs for two exciting sessions on current topics in iconography, a roundtable and a workshop, co-organized by Maria Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage of the Index of Medieval Art.

I. Saturday, May 11 at 10:30am [Session 346]

Encountering Medieval Iconography in the Twenty-First Century: Scholarship, Social Media, and Digital Methods (A Roundtable)

Stemming from the launch of the new database and enhancements of search technology and social media at the Index of Medieval Art, this roundtable addresses the many ways we encounter and access medieval iconography in the 21st century. Our five participants will speak on topics relevant to their area of specialization and participate in a discussion on how they use online resources, such as image databases, to incorporate the study of medieval iconography into their teaching, research, and public outreach.

Digital Information and Interoperability: Facing New Challenges with Mandragore, the Iconographic Database of the BnF

Sabine Maffre, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Ontology and Iconography: Defining a New Thesaurus of the OMCI at the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris

Isabelle Marchesin, Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA)

Iconography at the Missouri Crossroads: Teaching the Art of the Middle Ages in Middle America

Anne Rudloff Stanton, Univ. of Missouri

Medieval Iconography in the Digital Space: Standardization and Delimitation

Konstantina Karterouli, Dumbarton Oaks

Online Resources in the Changing Paradigm of Medieval Studies

Marina Vicelja, Center for Iconographic Studies, Univ. of Rijeka

II. Sunday, May 12 at 8:30am [Session 505]

Lost in Iconography? Exploring the New Database of the Index of Medieval Art (A Workshop)

This workshop will demonstrate how to get the most out of the new Index of Medieval Art database by using advanced search options, filters, and browse tools to research iconographic subjects. A short presentation will introduce the new subject taxonomy search tool that will further facilitate exploration of the online collection.

We look forward to an invigorating discussion on current issues in iconographic research and to sharing an update on the new database. You can find out more about the 54th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, held from 9-12 May 2019, including the full schedule here.

cordially invites you to join us for our

Thursday, September 20, 2018

4:00-6:00 pm

McCormick Hall, A Level

Join us for refreshments, meet the Index staff, and catch up with the medievalist community.

Enter a raffle to win books on medieval art.

Learn how the Index can support your research!

54th International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo, MI, May 9 to 12, 2019

Sponsored by the Index of Medieval Art, Princeton University

Organizers: M. Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage (Index of Medieval Art, Princeton University)

Stemming from the launch of the new database and enhancements of search technology and social media at the Index of Medieval Art, this roundtable addresses the many ways we encounter medieval iconography in the twenty-first century. We invite proposals from emerging scholars and a variety of professionals who are teaching with, blogging about, and cataloguing medieval iconography. This discussion will touch on the different ways we consume and create information with our research, shed light on original approaches, and discover common goals.

Participants in this roundtable will give short introductions (5-7 minutes) on issues relevant to their area of specialization and participate in a discussion on how they use online resources, such as image databases, to incorporate the study of medieval iconography into their teaching, research, and public outreach. Possible questions include: What makes an online collection “teaching-friendly” and accessible for student discovery? How does social media, including Twitter, Facebook, and blogging, make medieval image collections more visible? How do these platforms broaden interest in iconography and connect users to works of art? What are the aims and impact of organizations such as, the Index, the Getty, the INHA, the Warburg, and ICONCLASS, who are working with large stores of medieval art and architecture information? How can we envisage a wider network and discussion of professional practice within this specialized area?

Please send a 250-word abstract outlining your contribution to this roundtable and a completed Participant Information Form (available via the Congress Submissions website: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/submissions) by September 15 to M. Alessia Rossi (marossi@princeton.edu) and Jessica Savage (jlsavage@princeton.edu). More information about the Congress can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress.

Third in a series of short blog posts introducing new features of our online database

Have you tried out our Medium filter yet? As part of our ongoing series introducing specific features of our database to assist you in developing research strategies, let us direct your attention to the Medium field. First, you may ask, what exactly do we mean by “Medium”? In the Index database, “Medium” refers both to the materials that compose the work of art and to the methods of facture or technique employed in its creation. As Herbert Kessler rightly observes, “matter mattered in the Middle Ages,” and we at the Index wish to foster exciting new scholarship related to the iconography of materials.[1] A cursory glance at our Medium category under the “Browse” tab reveals an extraordinary array of materials and techniques. Objects may include materials ranging from “acacia” wood to “zeiler sandstone,” and all these materials might have been “hammered” and “punched,” or “chiseled” and “incised,” or subjected to many other possible means of manipulation.

But what if you are not ready for this level of specificity? For more general Medium searches, we have devised a series of basic category terms to help you find what you need: “stone,” “gems,” “wood,” “ivory,” “metal,” “enamel,” and “textile.” For example, let’s say you’re interested in representations of the Virgin Mary in any kind of stone. A keyword search for “Virgin Mary” on the database homepage will yield thousands of results in all media. So, if you want to limit your results to images in stone, simply find the “Filters” tab under “Advanced Search” and select “stone” under the Medium filter. Click on “Search,” and you will reduce your list to 1,752 records.

Now what if you know that you’re searching for representations of the Virgin Mary in a specific kind of stone? This time, let’s say you’re looking for marble sculpture. Instead of sifting through all 1,752 records for marble examples, just try selecting “marble” in the Medium filter. This should bring your results down to a mere 410 records.

You can also try refining your search with another filter. Interested in marble representations of the Virgin produced in medieval France? Add “France” in the Location filter, and you’ll narrow your results to 55 records.

So, whether you’re searching within broad categories or examining specific materials and techniques, try using the database’s Medium filter to adjust your search to your research interests.

Here are a few additional pointers:

So, as you undertake your research with us, we hope that you’ll give the Medium filter a try. As always, please feel free to send us questions or comments about any aspect of the IMA database. Contact us at theindex@princeton.edu. Matter matters…and so does your feedback!

[1] Herbert Kessler, Seeing Medieval Art (Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2004), 14.

Second in a series of short blog posts introducing new features of our online database

Have you tried our Language Filter yet? Since we at the Index of Medieval Art realize that some of the search features available to users of the new database may be unfamiliar, we thought that we ought to take some time to recommend and explain a few of them. This time, let’s discuss your use of language, shall we? Specifically, did you know that you can filter your searches to look for images that appear in the context of a certain language? Well, you can!

Say you’re interested in images of Joseph of Arimathea, for example, whether in a scene—such as the Deposition or the Entombment—or as an isolated figure. You might start with a simple keyword search for “Arimathea” on the database homepage, or you could also use the “Terms” tab on the “Advanced Search” page, checking “Description” and “Subject” in the “Search Fields” checklist, a strategy that currently yields a whopping 735 results.

Now let’s try using one of the filters. Simply switch to the “Filters” tab on the “Advanced Search” page. Feel free to explore, and try all or any of the filters. For the purposes of this demonstration, however, we’re thinking about language, so let’s start by narrowing our search to manuscripts. Simply select “Manuscript” in the Work of Art Type Filter (Example 1), then click “Search” again. You’ll discover that, in this case, you have nearly halved the search results to 373, but that’s still a lot of records to consider.

Now here comes the exciting part! If you know that you’re interested in a particular linguistic context, then you can add the Language Filter to your Advanced Search. There are currently 48 languages to choose from in the Index of Medieval Art database. For this demonstration, we’ve specified Greek (Example 2), so we’re searching for the word “Arimathea” where it appears in either the Subject field or the Description field, only in records for which the Work of Art Type is “Manuscript” and the language of the manuscript is “Greek.” Click “Search,” and you’ll discover that you have been able to filter your results down to a manageable 32 records!

Simple, n’est-ce pas?

You can easily change the Language filter to compare results from one language to another. Changing Greek to Armenian yields ten results. Church Slavonic yields six. Filtering for some languages may return nothing, others quite a lot. Latin, for example, returns 233 results, so you might want to add another filter to your search. For the time being, only the languages of manuscripts are identified in the database. Eventually, however, the Index database will identify the language or languages of every object that incorporates the written word.

You might have noticed that names of some languages include date ranges, as in “Middle English (1100–1500).” Although such dates can seem arbitrary, we try to differentiate among the stages of a language’s development. If you’re curious about how the Index defines a language, or about what sources we cite, you can click on the language name in the Language field of a Work of Art record. This will take you to a page where you can read the Language Details. There you’ll also find citations and external reference codes (Glottolog and ISO 639-3). On that page, there is also a list of all Work of Art References that include that language.

So, start exploring, and be sure to try out the filters available in the new Index of Medieval Art database. Also, please let us know what you think…but mind your language!

First in a series of short blog posts introducing the new features of our online database

Did you know that you can search The Index of Medieval Art for information about patrons of medieval art? The Index records both identified and unidentified patrons, the latter entered as grouping terms for types of patrons (Male, Female, Couple) and major monastic orders, such as Augustinian, Benedictine, and Carmelite. There are also general headings for anonymous male and female patrons (Male, unidentified and Female, unidentified). Names of churches, monasteries, and abbeys are given by their proper titles, such as Canterbury Cathedral, but might be further identified by location (e.g. Abbaye d’Anchin [Pecquencourt, France]).

For an overview of our patron headings, click on Browse at the top of the Index landing page. This will bring you to a list of over 900 names and grouping terms sorted in alphabetical order. To reach a specific entry, type the first few letters of a name into the search line at the top of the list. For instance, typing in “Blanche” will bring you to all Blanches from Burgundy, Castile, France, Navarre, and also the late 14th-century Countess of Geneva. Clicking on any patron heading will return a glossary entry comprising a biographical note with dates, alternate names of the patron, a bibliographic citation, an external reference for the authority source, and all the work of art examples linked to that patron.

Our patron entries are formatted in keeping with standard biographical authorities, such as the Library of Congress Name Authority File, the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), and Oxford References. Patrons are identified in the Index database by their roles and dates when these are known. When performing an Advanced Search in the “Terms” screen, you may prefer to keep the Match Type set to “Default,” which will search all parts of the heading. In the “Terms” window, a search can be formulated with keywords such as “Pope,” “Doge,” or “Prince,” using “Patron” in Search Fields to locate medieval patrons by their role. Similar keywords, along with keywords for place indicators like “Monastery” or “Convent,” can be searched against the “Patron Note” field, which will search the biographical notes in the patron glossary.

Many of the monastic patrons contain their locations in parentheses after the name of the community, so countries of patronage activity can also be searched as keywords. For instance, searching against “Patron” or “Patron Notes” with the keyword “Italy” returns over 150 records. This indicates artwork results for a patron who was active in Italy. From here, in the “Filters” window, the Date Slider can be used to refine results. The “Terms” search can be refined with any of the additional filters, including “Location,” “Medium,” “Style/ Culture,” and “Work of Art Type.”

Are you interested in finding out which female patrons were active in France in the 14th century?

In the Advanced Search “Terms” screen, enter the keyword “Female” and choose the Search Field “Patron” (keeping Match Type set to “Default,” as recommended).

Then, go to “Filters,” select “France” as a Location, and set the Date Slider to 1300 and 1399. This search should yield 27 examples, where a female patron is connected to the 14th century work made in any part of France.

*In results, please note that work of art records will include Main records indicated with a logo picture.

As you search for patrons in the new Index of Medieval Art database, bear in mind that visual representations of patrons are found in the Subject field. To find images of patrons, you can browse or search the Subject field with the keyword “Donor.” To read more about medieval patronage practices in general, you might find the Index’s 2013 conference publication Patronage, Power, and Agency in Medieval Art of interest. Enjoy refining your searches and browsing the range of patrons we record in the Index! And please remember that we are always happy to have your feedback. Get in touch with us at theindex@princeton.edu.

The personification of Wisdom in medieval art is usually grouped with other virtues, such as Justice, Hope, Prudence, Chastity, Poverty, Courage and Fortitude. While she works in communion with these sisters, she also performs her own distinct role. As the story goes, Wisdom was created by God before the world existed and is therefore in the position to offer humanity knowledge that will lead to its salvation. When Wisdom speaks in the Book of Proverbs, it is often to highlight her own importance and power. She calls herself a font of knowledge and a righteous helper who will reward those who follow her instructions. Wisdom says,

“By me kings reign and lawgivers decree just things. By me princes rule and the mighty decree justice. I love them that love me, and they that in the morning early watch for me shall find me. With me are riches and glory, glorious riches and justice….” [Proverbs 8.15–18 (Douay-Rheims Bible)]

This reward of Wisdom manifests in two ways: not only does she assist in saving the souls of those who heed her message, but she also has the authority to grant earthly power to individual rulers. The Index of Medieval Art records several scenes in biblical and secular narratives in which the virtue of Wisdom is a central character. Some relevant subjects in the Index include Christ: praising God’s Wisdom; Personification: Holy Wisdom; Personification: Celestial Beatitudes; and Holy Ghost: Gifts; and in narratives, Pèlerinage: Scene, Wisdom with Aristotle; Confessio Amantis: Scene, Darius, Sultan of Persia, seeking Wisdom, and De Consolatione Philosophiae: Scene, Wisdom showing Boethius Vision of Heaven.

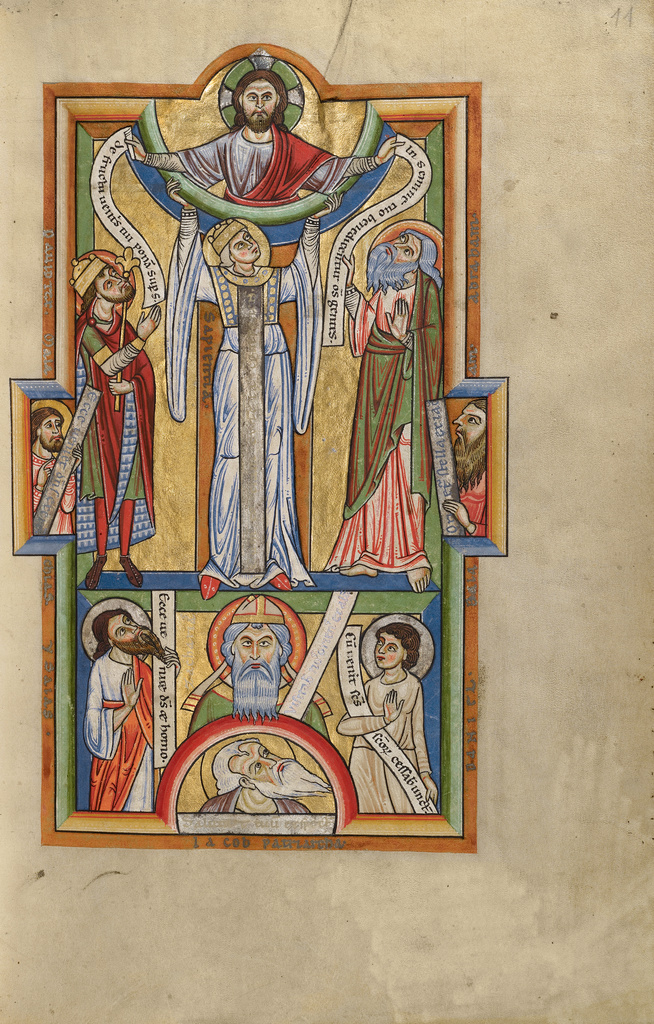

In some Semitic languages, the word we translate as wisdom literally meant to restrain oneself from evil, suggesting a conscious desire to avoid sin. Thus, a sinful individual cannot approach Wisdom, as illustrated in a Romanesque miniature on folio 11r in the Stammheim Missal made in Hildesheim [Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 64 (97.MG.21)]. Flanked by David and Abraham, a crowned Wisdom (Sapientia) is positioned beneath the half figure of Christ. Here she is in direct contact with the divine as she supports with raised hands the arc of heaven, the traditional separator of realms. In a sense, she has become a gatekeeper and mediator for Christ. Surrounded by earthly men, including Zechariah and Patriarch Jacob, Wisdom can also be seen as a kind of “ladder” to heaven, since her upright body forms an important link to the promise of salvation.

Wisdom’s spiritual authority is exemplified by a scene on folio 239v of the De consolatione philosophiae of Boethius, which shows her leading the Roman philosopher to God’s throne (New York, Morgan Library, M.396). They enter through a side door of the throne room, positioning Wisdom once again as the route to the divine.

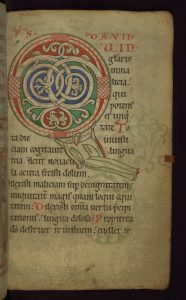

However, Wisdom also bore earthly authority, mentoring influential individuals such as Solomon, the Old Testament king of Israel and the traditional author of the biblical Book of Wisdom. This relationship is illustrated within an initial P (New York, Morgan Library, M.791). Against an ethereal gold burnished background, a veiled Wisdom crowns Solomon as a sign that she is at the root of his authority. By Wisdom—and by way of Wisdom—Solomon enacts what is so eloquently echoed in the verse of Proverbs: he will enjoy elevated status owing to the receipt of spiritual gifts; his reign is received in righteousness; and his rule is just.

This guest blog post was written by Rachel Dutaud, a summer student assistant at the Index of Medieval Art and a recent graduate in Art History and Ancient History from the University of St. Andrews. Over the 2017-18 academic year, Rachel will be working toward her MA degree in Archives & Records Management at University College Dublin. Her interests are medieval art history, iconography of female rulers, classicism, and archives.

One of the little thrills those us who do academic research get to enjoy — whether we specialize in the arts and humanities or engineering and sciences — is when our favorite topics come up in films or on television. Imagine the excitement for anyone who studies Andalusian architecture when the quasi-medieval show “Game of Thrones” received rare permission to film inside the beautiful Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain.

Now perhaps it will come as no surprise that several of us here at the Index of Medieval Art are looking forward to the next series of “Doctor Who” — and the premiere of the first female Doctor (to be played by Jodie Whittaker)! — when the Doctor’s complicated history with historical accuracy resumes. For those of you regrettably unfamiliar with “Doctor Who,” it is a long-running BBC show about a long-lived, possibly immortal, time-traveling alien, and history nerds are among the most avid Whovians. To understand why, just watch the episode in which Pompeii was destroyed because aliens were building a spaceship in Vesuvius! In another episode, we learned that William Shakespeare’s plays include secret spells that open portals to other parts of the universe!

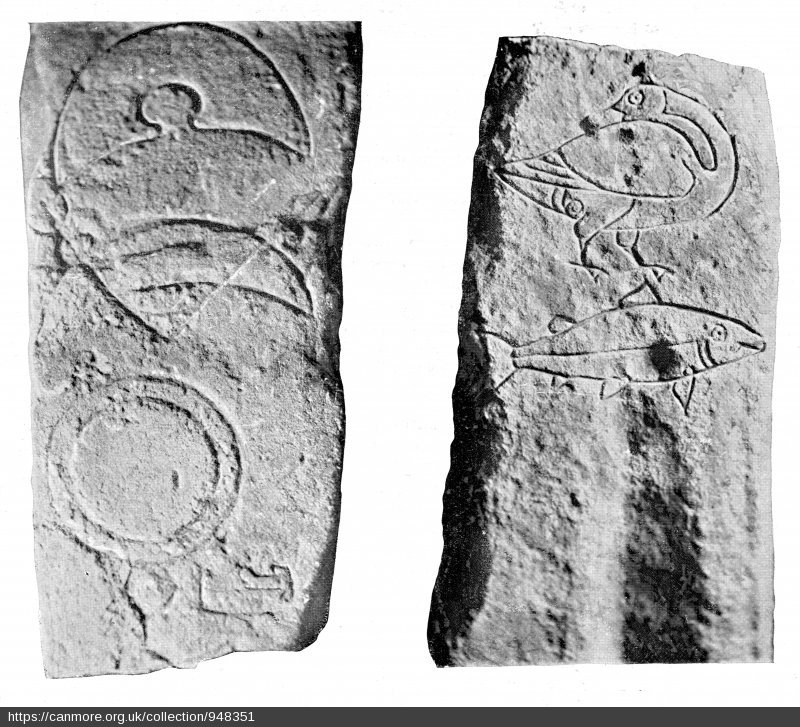

In the most recent series, the episode “The Eaters of Light” took place in Scotland in the second century AD. The Ninth Roman Legion, charged with the task of defeating the “barbarians” living in ancient Scotland, disappeared without a trace. When the Doctor and his companions investigate, things get a little strange. In the second century, the Roman Empire was trying desperately to maintain control of the lands of the “Picts” who lived north of what would very soon be the site of Hadrian’s Wall. The Picts are so called because these “painted people” (Picti) are mentioned in very early medieval texts. We know almost nothing about them, other than that they were fierce warriors, they painted their bodies before battle, and they left behind large stone monuments decorated with pictographic writing.

The Index of Medieval Art has almost 250 entries for “Pictish” artwork, most of which are large stones, either stelai or crosses. The stones usually appear in pairs, and the symbols carved on them depict inanimate objects like mirrors and combs, or crescents, and other geometrical shapes, as well as animals such as horses, dogs, birds and the enigmatic “Pictish beast.” It was this Pictish beast, a creature something like a hybrid of dolphin, horse, and dragon, or even (as some have argued), the Loch Ness Monster, that was the focus of “The Eaters of Light.” The episode proposed that it was a species of lizard-like alien monster that traveled through a great stone chamber-tomb in northern Scotland. Released in order to defeat the invading imperial army, it continued eating, threatening to consume all the light in our universe. Of course!

While this episode provides a fanciful interpretation of the Pictish stone carvings, it does actually highlight a point that art historians and archaeologists have been puzzling over for more than a century — just what do these symbols mean?

The stones were classified in the early twentieth century into three types, based upon their iconography and the level of detail in their carving. Class I stones, which date roughly to the fifth to seventh centuries, are relatively plain, and have only Pictish symbols inscribed upon them. Class II stones are slightly more ornate, with more effort obviously spent on not only carving the imagery but also on decorating the shape of the stone itself. They have not only Pictish symbols, but also Christian iconography such as very simple cruciform carvings. These are thought to date to the period of the seventh to ninth centuries, when conversion to Christianity was becoming more common in the region we now know as Scotland. Finally, Class III stones, which date to the later eighth and ninth centuries, are the most ornate. Their edges are highly decorated, the shape itself has been clearly hewn from the rock rather than simply incised upon it, and they have intricate carvings of knot-work and lace-work. Apparently used not only as upright markers or crosses but also as grave slabs, all of these Class III stones have explicitly Christian imagery, with many carved in the shape of crosses. None of them bear Pictish symbols, so these stones are interpreted as a last step in the Christianization of Scotland.

There are, however, two main difficulties in interpreting these Pictish symbol stones, though there are many theories as to what they represent. First, we are not entirely sure what they were for. Scholars have debated the issue for the last half century, arguing that they were monuments marking important meeting places or boundaries, or that they were memorials to particular individuals, families, events, or even that they might have been political statements opposing the spread of Christianity in early medieval Britain. Inscriptions are not helpful for interpretation either. While ogham writing in Ireland and Wales is found on stones that include Latin inscriptions, so that each stone is like a Rosetta Stone (with the Latin inscription in each case serving as a key to interpreting the ogham text), we do not currently have such a direct method of interpreting Pictish ideograms.

The second problem is the dating. Surviving Pictish stones suggest a development from the simple, presumably pagan, Pictish animals and shapes of Class I stones to the elaborate crosses in Class III. Like much archaeological evidence from the post-Roman fifth and early-sixth centuries in Britain, this dating is often based upon our expectations affected by early medieval texts like Bede’s Ecclesiastical History or Gildas’s On the Ruin of Britain, none of which were written in Britain in the period they describe. Unlike human or plant remains, stones cannot be radiocarbon dated. Even if we wanted to make the attempt at dating, for example, organic elements of the soil beneath the stones, only a few of the stones are actually still in situ. So the dating of the Pictish stones depends on parallels in manuscripts such as the Book of Durrow, and upon what we currently think about the history of the arrival of Christianity in Scotland. Even if we were able to determine with absolute certainty when exactly these stones were first inscribed and placed in the landscape, that account would still not consider the many succeeding generations and their many possible uses for these stones.

The Pictish stones in the Index of Medieval Art, especially the Class I stones, are part of a wider discussion of very early medieval society in Scotland. The Picts are the people that sixth-century and later texts blame for the beginning of the end of Roman Britain. Their raids along coasts to the south created defensive problems at a time when the Roman military presence in Britain was declining. Over the last fifty years or so, archaeological excavations of cemeteries in Scotland have increased our understanding of the monumental commemorations of death among the people who raised these decorated stones and crosses. The iconography on the stones that these people left behind is one of the few sources that modern scholars can work with to learn about the Picts and their world — and it also turns out to be a great source of inspiration for science fiction television.

This guest blog post was written by Janet Kay, a CLSA-Cotsen postdoctoral fellow at the Princeton Society of Fellows. She studies the history of fifth-century Britain, looking at burial practices to study a period for which there are no surviving texts. Janet uses material culture and funerary rites as primary sources to explore how fifth-century communities understood themselves and their newly-arrived neighbors from the continent and how invested they were in maintaining connections with their Roman past.

The month of June marks the passing of two historically consequential rulers: the fourth-century Roman emperor Julian, posthumously referred to as Julian the Apostate, and the twelfth-century Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, also known as Frederick Barbarossa. Their untimely deaths shocked the Late Antique and Medieval worlds, respectively. On June 26, 363, Julian was mortally wounded in the battle of Samarra during a Roman military campaign against the Persians. According to various sources, a spear delivered by a member of the Sassanian cavalry pierced his liver, and he subsequently died from the mortal blow some three days later. June 10, 1190, marks the day on which Frederick Barbarossa drowned in the Saleph River (the Göksu in modern Turkey) in the middle of the Third Crusade, the Latin West’s attempt to recapture the Holy Land from Saladin. The deaths of both leaders in the middle of critical military campaigns generated either anxiety or derision among their contemporaries, as underscored in subsequent medieval representations of the two emperors.

Posthumous medieval representations of Julian, the last Roman emperor who championed paganism, are almost always critical. For example, a lavishly illuminated ninth-century Byzantine manuscript of Gregory Nazianzen’s homilies (Paris, BnF, gr.510, fol. 374v), depicts the ruler accompanying the pagan philosopher Maximus of Ephesus and venerating idols. In Simone Martini’s fourteenth-century fresco cycle in the Chapel of Saint Martino within the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi, the figure of Julian the Apostate serves as an arrogant, pagan, visual foil to the saintly Martin of Tours, who is shown renouncing military life for his Christian beliefs. Depictions of Julian’s death are even more damning. By the early sixth century, accounts surrounding Julian’s death shifted away from a battle against the Persians and amplified the legend of Saint Mercurius (identified as Mercurius of Caesarea in the Index database), a Byzantine soldier saint who rises from the dead and kills the pagan emperor with his lance or sword.

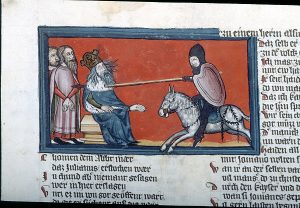

Although this legend developed in Eastern sources, it grew in popularity in the Medieval Latin West, even making an appearance in Jacopo de Voragine’s thirteenth-century Golden Legend. In a fourteenth-century Christherre-Chronik miniature in the Morgan Library (New York, PML, M.769, fol. 327v), the figure of Julian is portrayed as an elderly medieval monarch lanced by a fully armored Saint Mercurius astride a galloping horse.

In contrast to the overwhelmingly uncomplimentary medieval portraits of Julian the Apostate, representations of Frederick Barbarossa generally evoke the idea of imperial majesty and power. The so-called Cappenberg head (c. 1160), a reliquary that originated as a portrait of Frederick, effectively conveys an image of grandeur and stability through its precious materials and antique visual language. Yet a miniature drawn, less than a decade after his death, in Peter of Eboli’s De Rebus Sicilis (Bern, Stadtbibliothek, 120 II, fol. 107r) betrays the unease surrounding the emperor’s accidental passing. Inscribed FREDERICUS IMPERATOR IN FLUMINE DEFUNCTUS, the drawing depicts the ruler falling off his horse and drowning in the water, his crown lying ignobly in the riverbed. As if to combat the contemporary whispers that Frederick died without confessing his sins, the illuminator purposely included an image of the ruler’s soul as a swaddled infant held aloft by an angel and given to the Hand of God emerging from heaven. In so doing, the artist was participating in a larger, concerted effort to salvage Frederick Barbarossa’s reputation for posterity as a noble and most Christian emperor.

The Index is pleased to announce the speakers for two honorary sessions at the International Congress on Medieval Studies to be held at Western Michigan University (Kalamazoo, MI) on May 11-14, 2017.

Organized by Judith Golden and Jessica Savage, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Presider: Judith H. Oliver, Colgate University, Professor Emerita

This session will examine the interaction between words and images in medieval manuscripts as they shape the reader-viewer’s experience of the book. How do texts and images interact on the page? How did medieval readers respond to the varied discourses between images and texts? This session endeavors to open up new perspectives in describing, analyzing, and contextualizing manuscript illumination according to their intrinsic or peripheral textual elements. Papers in this session will undertake a close study of a particular manuscript and will expand upon theories for image-text composition by reviewing evidence of an artist’s written instructions; reading images with layered text additions, omissions or annotations; and recovering the reader’s experience through text and iconography.

“Artists and Autonomy: Written Instructions and Preliminary Drawings for the Illuminator in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea (HM 3027)”

“Bodies of Words: Text and Image in an Illustrated Anatomical Codex (Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 399)”

“A Votive ‘Closing’ in the Claricia Psalter (Walters MS W.26)”

Presider: M. Alison Stones, University of Pittsburgh, Professor Emerita

This session will examine the varied “visual signatures” of manuscript patrons, including dress, gestures, posture, and attributes of donor figures; heraldry and personalized inscriptions; marginal notes, colophons, dedications, and other signs of ownership and use in medieval manuscripts. Building on scholarship presented in the 2013 Index of Christian Art conference Patronage: Power and Agency in Medieval Art, this session will investigate the dynamic system of patronage centered on the interaction of owners with their books (whether as creator, patron, commissioner, or reader-viewer). Papers will address the importance of gender and social roles in book production, use, and readership, or will expand upon the role of patron as instigator in the book creation process, from payment to design.

“How Owner Portraits Work”

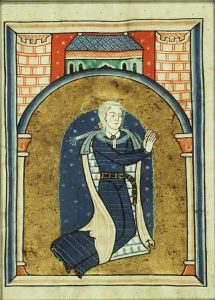

“The Patroness Portrait of the Fécamp Psalter (c. 1180): An Unknown Example of Royal Artistic Commission in Angevin Normandy”

“Patron Portrait as Creation Myth: On ‘Production Scenes’ in Illuminated Manuscripts”

In July 2016, Adelaide Bennett Hagens retired from the Index of Christian Art at Princeton University after fifty years of dedicated research and scholarship. She studied under Robert Branner at Columbia University and joined the Index during the directorship of Rosalie Green. Adelaide has studied medieval art in a variety of media, but her passion at the Index and in her personal research has always been manuscript illumination, particularly of the Gothic period. Her publications include “Some Perspectives on the Origins of Books of Hours in France in the Thirteenth Century,” in Books of Hours Reconsidered, edited by Sandra Hindman and James H. Marrow (2013); “Making Literate Lay Women Visible: Text and Image in French and Flemish Books of Hours, 1220–1320,” in Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces, edited by Elina Gertsman and Jill Stevenson (2012); and “The Windmill Psalter: The Historiated Letter E of Psalm One,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980). In two sessions, we celebrate Adelaide’s accomplishments and recognize her contributions to the Index of Christian Art and to the wider medieval and academic community.