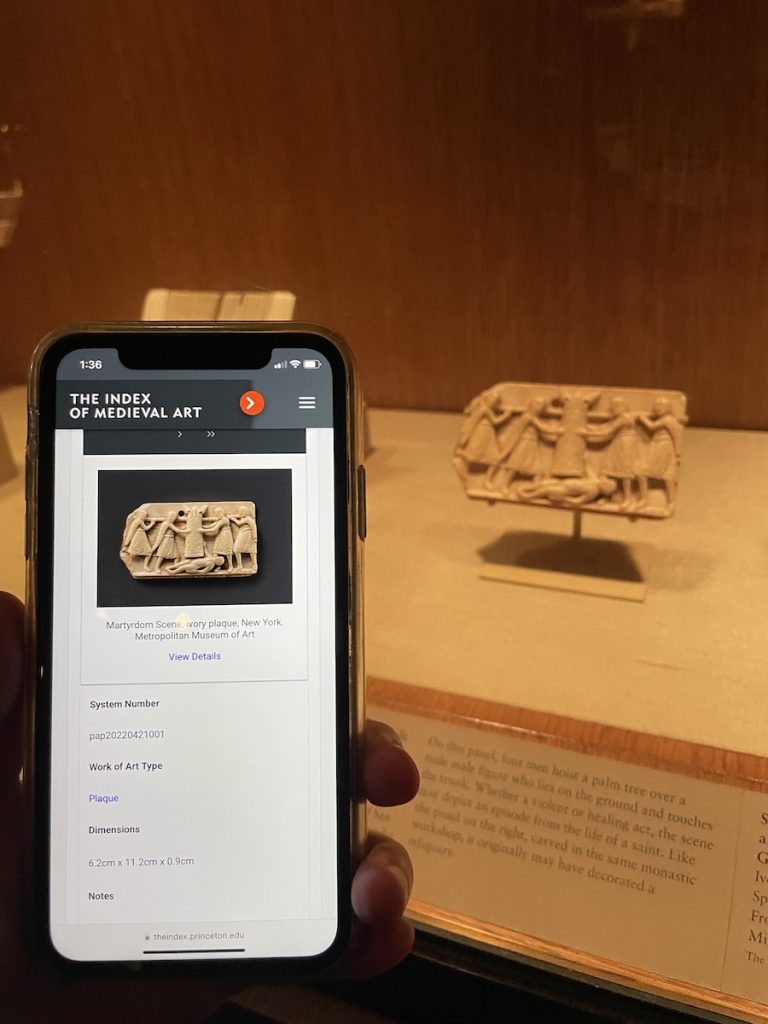

This summer the Index of Medieval Art achieved a milestone in our cataloging mission: the completion of all ivory objects in our print photo archive. In all, more than three thousand objects from the Index’s card catalog have been added to the Index database, significantly enhancing the online collection and establishing the Index as a more vital resource for the study of medieval ivories. The new records include chess pieces, croziers, caskets, combs, retables, diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs, knife handles, mirror cases, oliphants, pyxides, statuettes, and much more! Many of the works of art date to the Gothic period, but late antique, early medieval, Romanesque, Carolingian, Siculo-Arabic, and Byzantine works are also well represented. The materials and techniques categorized as “ivory” were also surprisingly diverse, including carvings in walrus tusk, also known as morse, as well as in horn, bone, antler, and even a ceremonial staff made from narwhal tusk.1

The ivory cataloging project was begun shortly after staff returned to in-person work during the later stages of the pandemic. Index research staff worked from inventories of the photo files made by former student assistant Michele Mesi in 2019.2 Many of the photo files dated from the 1930s to 1950s, and they usually provided a subject and photograph with a bibliographic reference, though sometimes they included much less! Working from the clues left by earlier generations of Indexers, the current crew shared key publications and relied when possible on databases, such as the Courtauld Institute’s Gothic Ivories Project, to work through the records alphabetically by location and collection.3

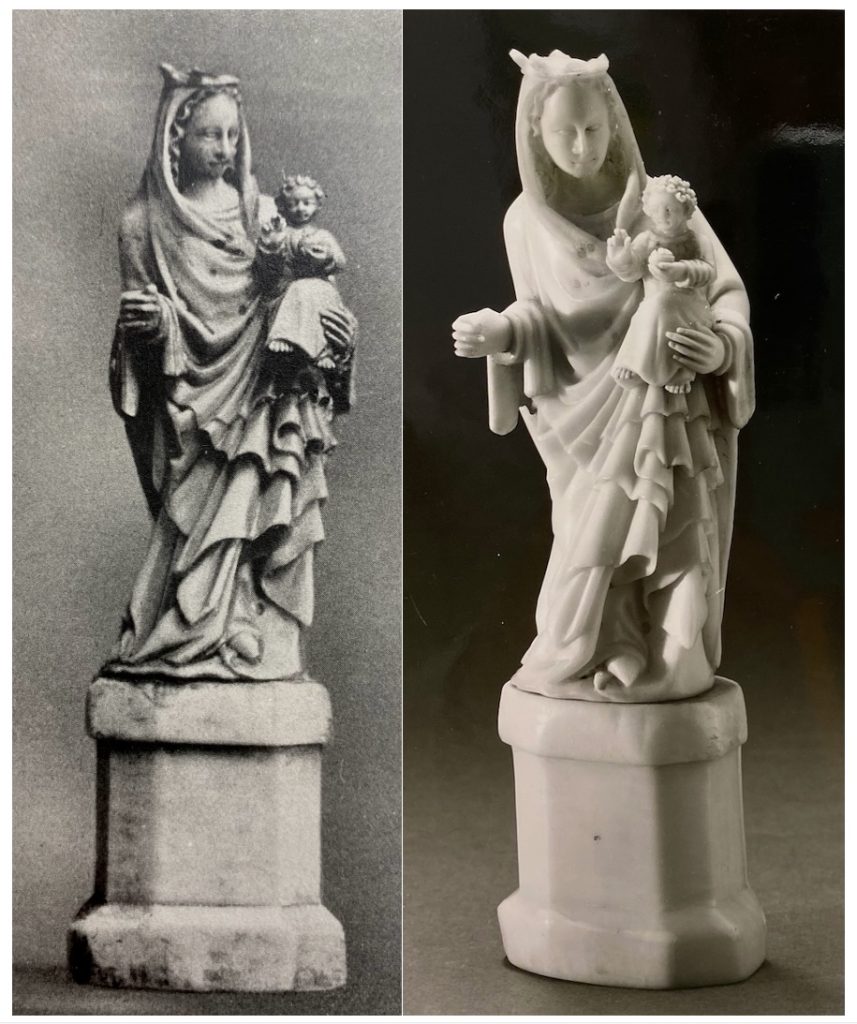

Sometimes we found research clues in unorthodox sources. While researching an early fourteenth-century statue of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna del Fiore, Art History Specialist Jessica Savage found images shared by the Associazione di Festeggiamenti di Lugnano, Rieti on Facebook. According to the association’s website, the statue is mounted on a gilded decorative support and processed through the streets of Lugnano during the “Festa della Madonna del Fiore” every first Sunday of September.4 It was fascinating to see the medieval relic in celebratory use to this day, and it is just as easy to imagine the lives of these various objects as they were gifted, traded, used, venerated, and now discoverable online with the Index database–many digitized for the first time.

Many of the objects and fragments on which we worked had been dispersed either before or after their records were created, and some items or even whole collections had changed hands. Sometimes this provoked unexpected collaborations: in one case, Art History Specialist Maria Alessia Rossi cataloged the right wing of a diptych in the Musée de Cluny depicting the Coronation and Dormition of the Virgin, and then, about a year later, Savage found the other wing, with the adjoining scenes of the Last Judgment and Adoration of the Magi, separately cataloged in the file of the Paris Cabinet des Médailles. The diptych wings are now digitally reunited as Index System number mar20230306003.

Reflecting on the ivories project, Index Director Pamela Patton said, “One of the most exciting things about cataloging the ivory backfiles was the chance to bring elements of a single object that had been dispersed over time into a single work of art record, as for the Casket of Saint Emilianus (San Millán), a reliquary made in the eleventh century but damaged when the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla was sacked in 1089.” Some of the ivory plaques remain in the monastery, but others were dispersed to at least seven different museums in Europe and the United States. Patton recalled, “Bringing together images and metadata for all these works, including one plaque that was lost in World War II but preserved in a German photograph, was a very satisfying endeavor.”

Byzantine rosette caskets were another category that some researchers may find intriguing. Art History Specialist Henry D. Schilb created a record for the Hermitage Museum’s inv. no. Ѡ17, now Index System number hds20250128001, one of a group of similar caskets cataloged by the Index over the years, with examples in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (inventory number Kg 54:219, Index System number 77286) and the Cleveland Museum of Art (inventory number 1924.747, Index System number 77285). Known for the prominent use of rosette ornament, this group of caskets has also attracted the attention of no less eminent a scholar than Princeton alumnus Justin Willson, whose recent article discusses why we find among scenes of Adam and Eve the figure of Plutus holding a moneybag.5

New iconographic subjects encountered during our work on ivories were sometimes added to the Index database during cataloging. For example, the bust portrait of “Ulpia Sirica,” a second or fourth century woman from Rome, was discovered by Rossi in the ivory files. The only known depiction of Ulpia on this opus sectile-style plaque, made of marble, blue and green enamels, glass paste, and painted bone and ivory listels, was buried by a landslide in the late 1900s. Her portrait is last known to have been embedded in a Latin epitaph in the Catacombs of Saint Agnes in Rome; it is preserved in a late nineteenth-century watercolor by Salvatore Merola, kept in the diary of Ubaldo Giordani.6

Additionally, the little-known female saints “Oderade of Quedlinburg,” “Agnes II of Quedlinburg,” and “Pusinna, Saint” inspired new iconographic research by Art History Specialist Catherine Fernandez during her work on the Reliquary of St. Servatius now housed in the Stift Quedlinburg, Domschatz. The rarely depicted religious women, a prioress, abbess, and hermit, respectively, appear in an iconographic grouping, or relic list, with other saints on the bottom enamel panel of the Reliquary of St. Servatius. The ivory reliquary was made in Fulda or Metz around 870 with gem and metalwork additions ca. 1300.

The ivory cataloging project produced a new authority in the Style/Culture category. We added the heading “Forgery” to describe objects that, although executed in a “medieval” style, were actually—and often with deceptive intent—produced by more modern artists.7 The project also required the verification of a great many locations, part of Schilb’s ongoing project to make the location data used by the Index as accurate and precise as possible.

Indexers celebrated the completion of the ivories project with all staff at an in-house celebration that featured appropriately pale but delectable treats (popcorn, burrata, white chocolate-covered almonds, vanilla meringues!) and offered a chance to reminisce about highlights from the project.8 Many more ivory objects remain to be cataloged by the Index in years to come, but for now we are thrilled to make available online all the objects that have been cataloged by the Index to date. We acknowledge there might still be missing or outdated information on some of these records. Sometimes images could not be tracked down, current locations could not be verified, or works were presumed lost or destroyed. Our cataloging efforts will always be a work in progress, and we remain open to your corrections, suggestions, and questions.

Please reach out to us via email, and be sure to follow us here for all our latest updates. You can also find us on Facebook and Bluesky.

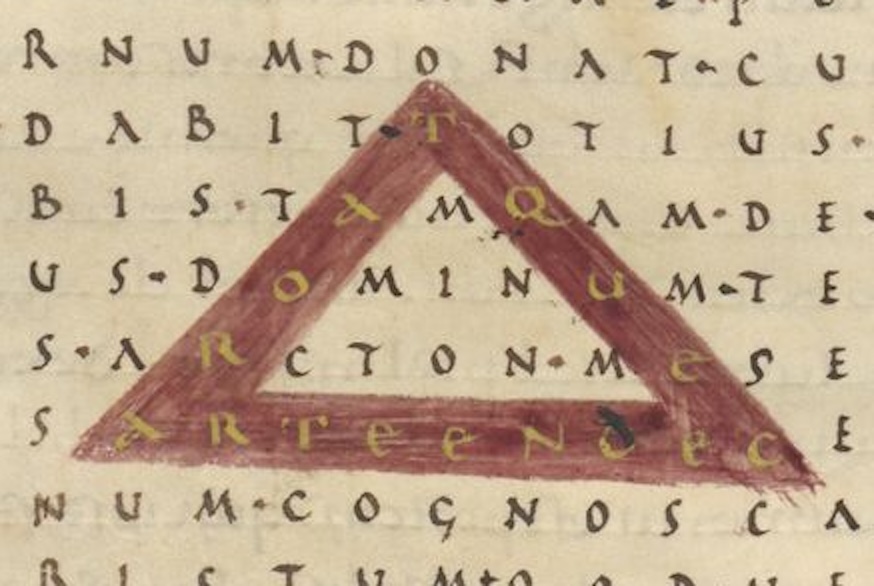

Please save the date for the next Index of Medieval Art conference, “Art and Proof in the Ninth Century.” Organized by Professors Beatrice Kitzinger and Charlie Barber in collaboration with the Index and co-sponsored by the Department of Art & Archaeology, the conference will follow on the department’s 2025 Kurt Weitzmann Memorial Lecture by Francesca dell’Acqua (Università di Salerno) on December 5, which will double as the conference keynote.

The springing point of the conference is December 825, when the city of Paris witnessed a synod devoted to the discussion of the status of images in the Carolingian world. This meeting, convened in response to flare-ups of the “image question” in Constantinople and Rome, set forth a Latin Christian understanding of images that would remain dominant in early and high Medieval Europe. The dossier affirmed the value of images as mnemonics and devotional aids but ultimately re-asserted the primacy of verbal media in the religious sphere. However, as the conference speakers will show, artistic evidence itself suggests that ninth-century approaches to the role of images complicated and exceeded those prescribed for them by the bishops at Paris.

Prof. dell’Acqua’s lecture will directly address the Roman–Frankish context in which the Paris synod unfolded. The papers that follow will dramatically expand the lens through which we view the central questions by considering the notion of proof in the ninth century through a much wider lens, reaching from the British Isles to Japan and from Georgia to Egypt and representing a wide range of languages and religious communities. Key themes include: the terminology surrounding images and their uses; questions of representation, semiotics, authenticity and truth; propositions that need proving and their modes of proof; the functions and status of images in society, and how these are secured; how occasions for image discussion reflect on local circumstances and priorities; ways in which discussing the validity of images intersects with politics, diplomacy, or self-fashioning; whether the notion of proof in relation to images, which emerged from a specific Christian and European moment, resonates in other contexts; and whether a more global perspective provides different valences for the concept of “proof” through artwork.

Francesca Dell’Acqua [Weitzmann Lecture, Dec. 5, 2025] Associate Professor, Università di Salerno

Andrea Achi, Associate Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Nourane Ben Azzouna, Associate Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anouk Busset, Lecturer, Université de Lausanne

Zsuzsanna Gulacsi, Professor, Northern Arizona University

Rachel Saunders, Assistant Professor, Princeton University

Alexei Sivertsev, Professor, DePaul University

Erik Thunø, Professor, Rutgers University

Anca Vasiliu, [Respondent] Director of Research, CNRS, Sorbonne Université

About 45 people attended the hybrid session sponsored by the Index of Medieval Art at the 60th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, MI on May 8, 2025. “Breaking the Mirror: New Approaches to the Study of Medieval Images” asked scholars in all fields to think afresh about what they can learn from medieval images, and especially how their potential to go beyond mere illustration—to aspire, deceive, and even fantasize—complicates what and how medievalists can learn from them. The session roster included:

“Byzantine Images and Religious Truths: A Wide-Angled View.”

Diliana Angelova, University of California–Berkeley

“The Imago agens in the Illumination of the Luttrell Psalter: Expressing the Ineffable that Is Beyond Words.” Christina Caroline ten Wolde-Marshall, Independent Scholar (Wales)

“Portrayals of the Patriarch: The Pictorial Slander and Celebration of Ignatios.”

Lora Webb, Emory University

The three papers provoked a lively discussion and a dynamic start to the three-day conference. Hearty thanks to our three speakers and their audience, both in person and online!

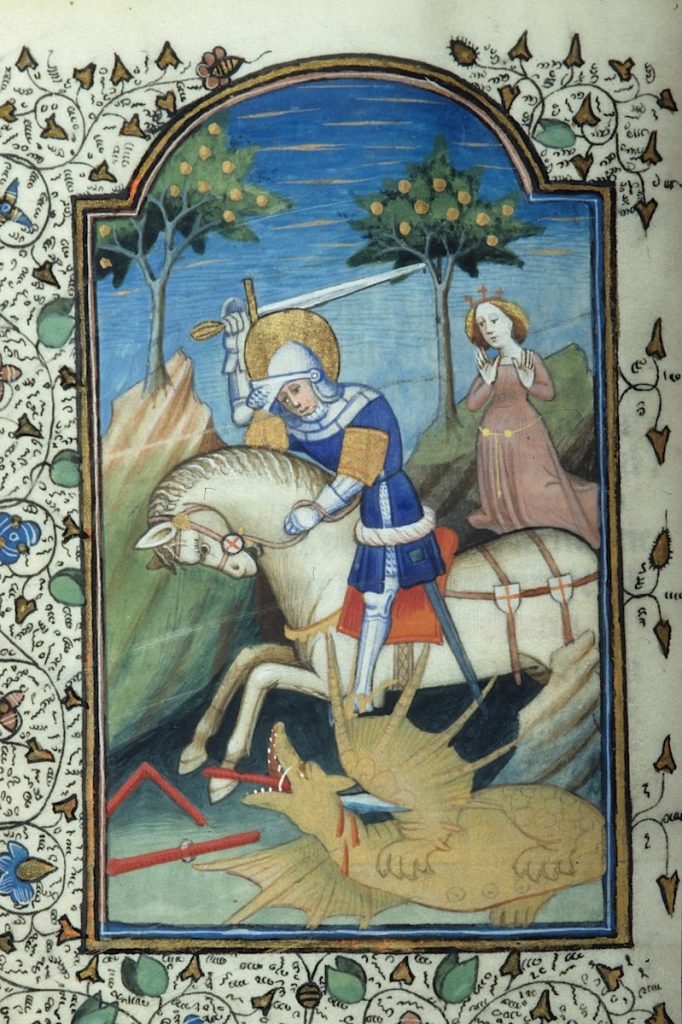

Are you familiar with the popular iconography of the saint whose feast day falls on April 23? If you’ve ever been to an English pub, you probably are, even if you didn’t realize it! According to medieval legend, Saint George of Cappadocia was the third-century saint and martyr who slew a dragon. Usually, George is represented as a knight mounted on a horse. Sometimes shown carrying a cross-inscribed shield, his red and white armorial attribute, he thrusts his lance into the jaws of the dragon under his horse’s hooves.

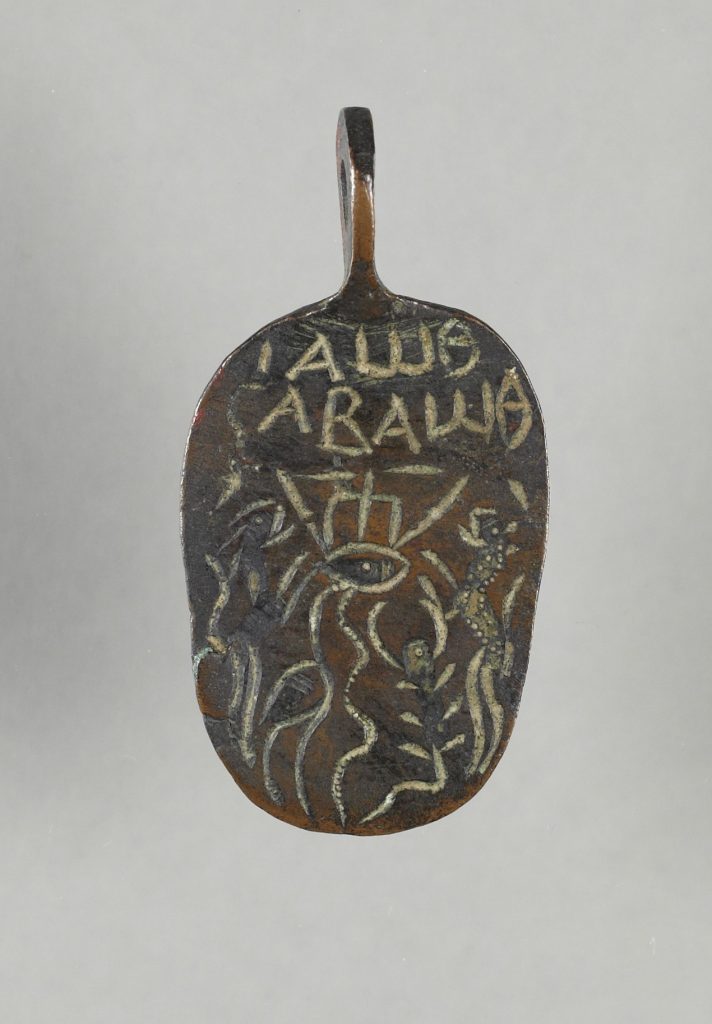

George’s heroic posture was modeled on the iconography of other saints and mythological figures. Theodore Tyro and Demetrius of Thessalonica, for example, also slew beasts in the name of vanquishing evil. Carrying talismanic or protective power for people threatened by worldly dangers, dragon-slayer images decorated many small, portable objects, including ampullae, lamps, carved gems and small plaques from the late antique, Byzantine, and Coptic worlds.1 Building on narratives of his heroism, tales of George’s life and deeds spread throughout medieval Europe with Crusaders returning from the East. By the high Middle Ages, the Golden Legend, a compilation of saints’ lives by Jacobus de Voragine, fleshed out the life of George with a rescue narrative of a king’s daughter and inspired numerous visual representations in different media.2

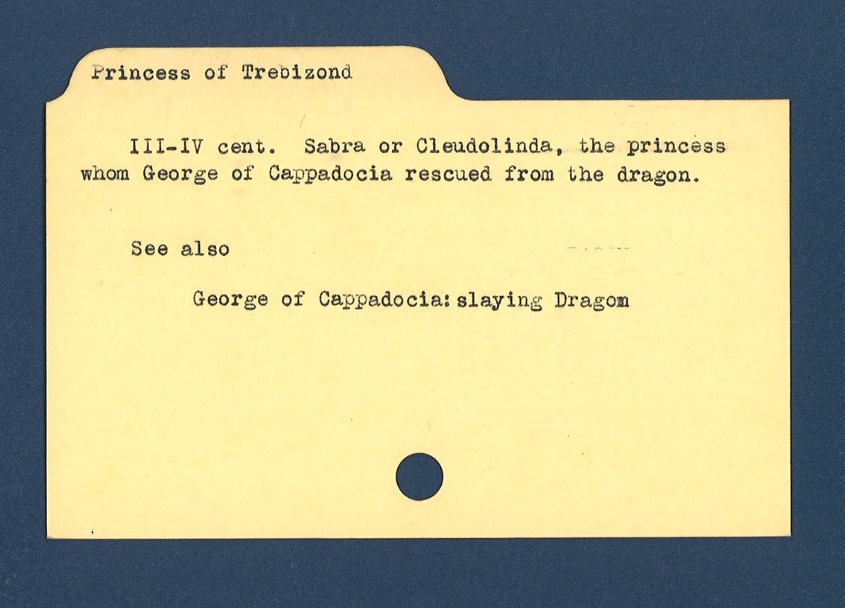

Depictions of the rescue legend, which follow standard iconography for George’s slaying of the dragon, often insert the princess as a minor character of relative insignificance. But is she insignificant? Traditionally identified as a third or fourth century Komnenian princess of Trebizond, she is sometimes named Sabra or Cleodolinda (or Cleolinda, Cleudolinda) (Fig. 1). According to the legend, the princess was weeping profusely, anticipating her certain death as the next human sacrifice to the dragon, when George arrived at a town called Silene in Libya. He pledged to help her, and he rode toward the dragon with his sword drawn.3 In swift succession, George pierced the dragon and the princess bound her girdle around the beast’s neck. She led it back to the townspeople alive which brought about the people’s mass conversion to Christianity.

In some earlier depictions of the legend, the princess appears with prominence, including on a Romanesque capital from a monastery in Saint-Pons-de-Thomières now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the capital face, the princess wears a long dress, props one hand on her hip, and extends a flower toward George (Fig. 2). Around the other side, George kneels behind his shield, trailing a coiled serpent that approaches the princess from behind. Her thank offering to George in the midst of his attack on the dragon suggests that there will be a good outcome despite the violence surrounding her.

In another Romanesque capital from the abbey of Saint-Pierre of Airvault in Poitou, the princess stands behind George, although he rides away from her, effectively separating her from the dragon’s reach (Fig. 3). With George exiting left, the princess becomes a key figure of interest to viewers gazing upward at the capital. Here, she maintains a stoic stance, and, in ironic juxtaposition with the nearby head of a menacing grotesque, her arms are crossed over her body in a way that suggests patience and perseverance in the face of danger.

By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the iconography of the princess and her role in George’s slaying of the dragon were handled with more flexibility, especially in manuscript illumination.5 Some examples, such as the Hungarian Angevin Legendary, illustrate the narrative more literally, showing the princess tethering the dragon or leading it away by its makeshift leash (Fig. 4). In this variant of her iconography, the Princess of Trebizond is actively engaged with George’s feat and secures the dragon in one forceful pull.

At George’s suffrage in illuminated prayerbooks, especially in Books of Hours, the princess often appears behind the slaying scene, kneeling in prayer, and protected a distance.6 But in some of these late medieval depictions, she tends a flock of sheep, sometimes holding one sheep on a lead, or she simply raises her hands in surprise at George’s victory (Fig. 5).7

In all these images, the princess functions as more than a mere attribute of George. Instead, she is actively reimagined as part of the narrative. Artists creatively customized their images of Georgian legend to not only explore the princess’s instrumental role in her rescue but to highlight her intercessory function in saving the townspeople–in a literal sense and by their newfound faith. Whether showing her as prayerful, gracious, surprised, or tethering the dragon, the iconography of the princess offers a versatile model of female agency, one that likely inspired her viewers.

We can find echoes of such rescue narratives in other ages and media. If you have played the classic Super Mario Bros. video game, then you know the game’s mission: rescue Princess Peach! As aficionados know, the eighth and final world of the game culminated in an underground battle with Bowser, the hammer-hurling, spiky-shelled antagonist (Fig. 6). If you hurled enough fireballs back at Bowser, he overturned and descended into an abyss off screen, allowing Mario to advance over the bridge and reach the princess on the other side. Much like the Princess of Trebizond, Princess Peach had to be rescued, and she, too, has been reimagined over time: her characterization within the Nintendo empire of games and films eventually evolved from damsel in a dungeon to a fighter in her own right.8

You can still find the iconography of George slaying the dragon in the modern world, often in a reduced composition of equestrian, saint, and dragon. Once you know what you’re looking for, you’ll spot George in any number of settings, especially on pub signs like the one on my local haunt when I was a grad student in London (Fig. 7). Whether under his sign or not, those who cheer to Saint George today would do well to remember this: once upon a time, a princess filled with purposeful character also conquered a beast.

Thank You, Saint George! Your Quest is Over.

Appendix

The Index subject files provide a starting point to locate examples of the Princess of Trebizond in the six works of art:

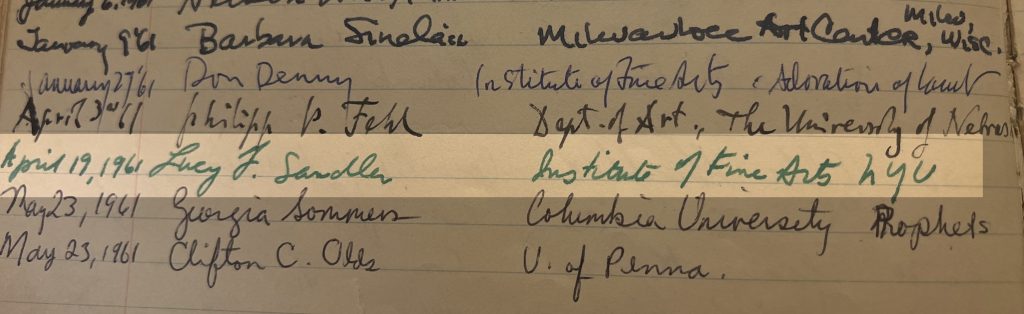

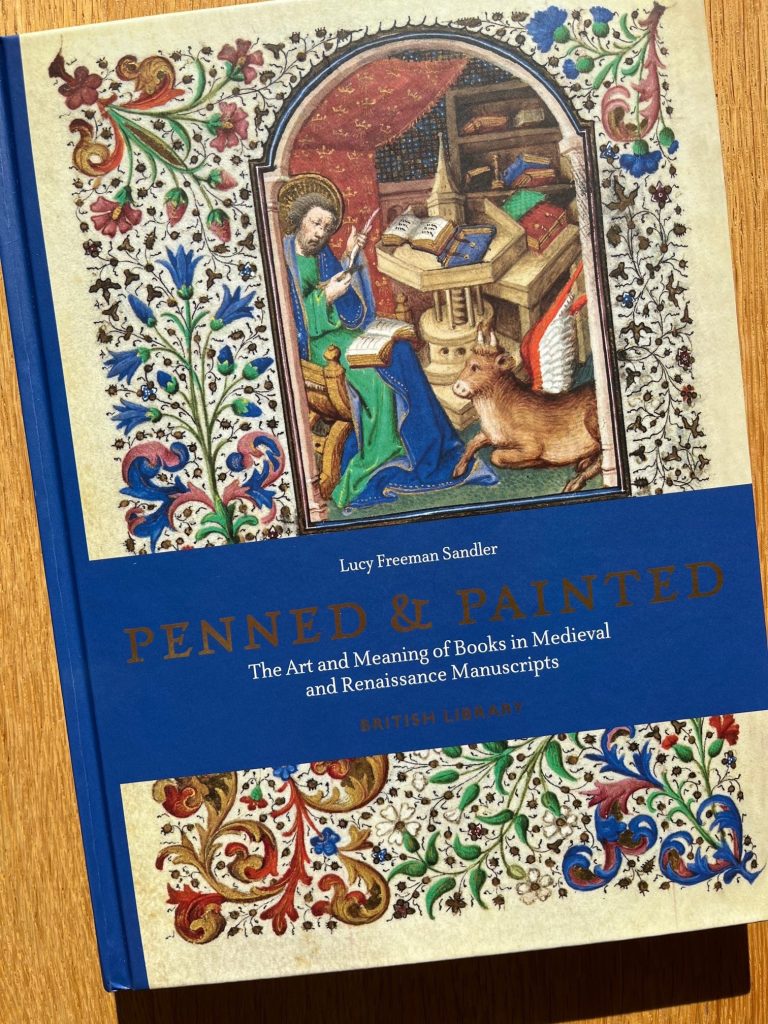

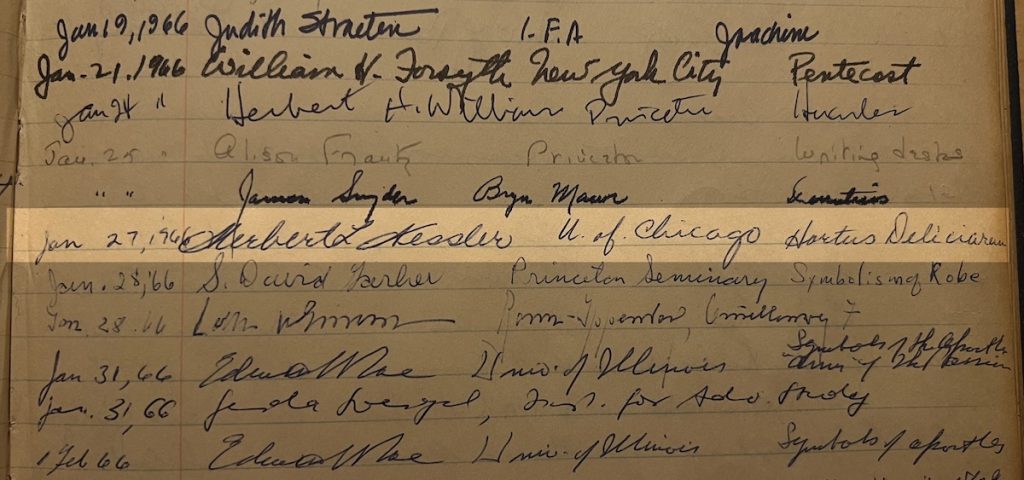

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections and warmly thank Lucy Freeman Sandler, Professor Emerita, Institute of Fine Arts of New York University, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I began to study painting at Queens College but my first undergraduate art history course focused my interest in a new direction, and, inspired by a charismatic medievalist, Frances Godwin, I decided to study the art of the Middle Ages on the graduate level. On Prof. Godwin’s advice I applied to and was accepted at Columbia University and took courses with Meyer Schapiro, a formative intellectual experience, and then with John Plummer, who was then himself completing a Ph.D. with Schapiro. It was Plummer’s course, called “Gothic Painting,” which was primarily about illuminated manuscripts, in which I “discovered” marginal illustrations, a topic that became the subject of my master’s thesis. For my own Ph.D. I transferred to the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University (they generously awarded me a scholarship), eventually completing a dissertation on the Psalter of Robert de Lisle (London, British Library, Arundel MS 83).

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

I cannot remember the date of my first visit to the Index, which Index records indicate was 1961, during the time I was working on my dissertation. I have certainly used the Index many times since, and have known all its directors since Rosalie Green, although, to my regret, I did not meet her.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

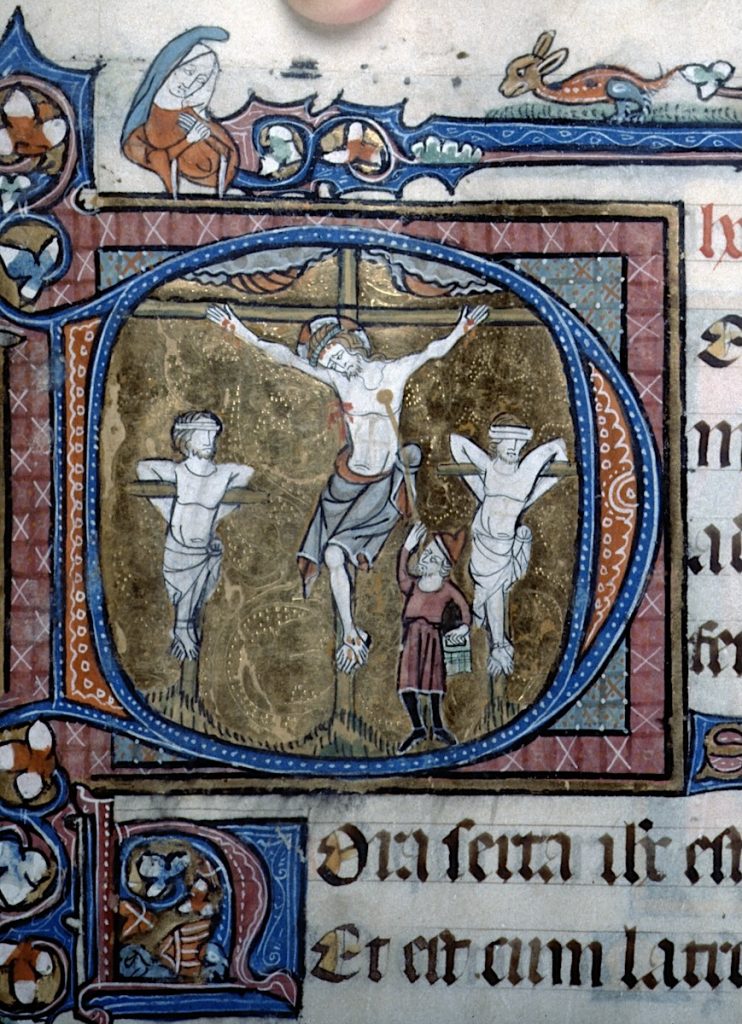

I remember at least one visit, probably sometime between 1961 and 1964, when I was trying to determine the date during the Gothic period at which the crossed feet of the Crucified Christ changed position. I must have looked at hundreds of photos of every late thirteenth and fourteenth century Crucifixion at the Index. I can’t say that I came to any definitive conclusion but I certainly learned a lot about Crucifixion representations. I have found the online version of the Index invaluable, especially in connection with my latest book, Penned & Painted: The Art and Meaning of Books in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts (London: British Library, 2022), for which I did much of the research during Covid.

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I have attended quite a few Index conferences and have spoken at several, including “The Weingarten Office Lectionary and Passionale in New York and St. Petersburg,” in Romanesque Art and Thought in the Twelfth Century in Honor of Walter Cahn (October 2006); “One Hundred and Fifty Years of Study of the Illuminated Book in England: The Bohun Manuscripts from the Nineteenth Century to the Present,” in Gothic Art & Thought in the Middle Ages: A Conference in Honor of Willibald Sauerländer (March 2009); “The Bohun Women and Manuscript Patronage in Fourteenth Century England,” in Medieval Patronage: Patronage, Power and Agency in Medieval Art (October 2012); and “Princeton Garrett MS 35 and Homeless English Gothic Manuscripts,” in Manuscripta Illuminata: Approaches to Understanding Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts (October 2013). All these were subsequently published under the editorship of Colum Hourihane. I also contributed a tribute to John Plummer: “John Plummer: A Reminiscence,” in Between the Picture and the Word: Manuscript Studies from the Index of Christian Art, ed. C. Hourihane (University Park, PA, 2005), 9–11.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As co-editor of the Index-based Studies in Iconography, from 2009–2015, I hoped to serve the mission of the journal, as it has continued to the present, to publish “innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed.”

Thank you, Lucy! As the home for Studies in Iconography we’re committed to publishing innovative work in iconographic studies, and we’re grateful for your invaluable contributions to the Index over so many years.

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2025.

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to introduce a new AI assistant to support users in their research on medieval iconography. The new IAI (Index Artificial Intelligence) aims to save researchers time and energy by aggregating search results into a digestible single image for use in your research paper or article. No more online filters to manipulate, index drawers to pull out, or search results to sort: simply tell IAI what you’re looking for and it will deliver an image that distills all the essential features of your search terms into the quintessential example for your next research project. And because it’s AI generated, no one will worry about copyright permissions.

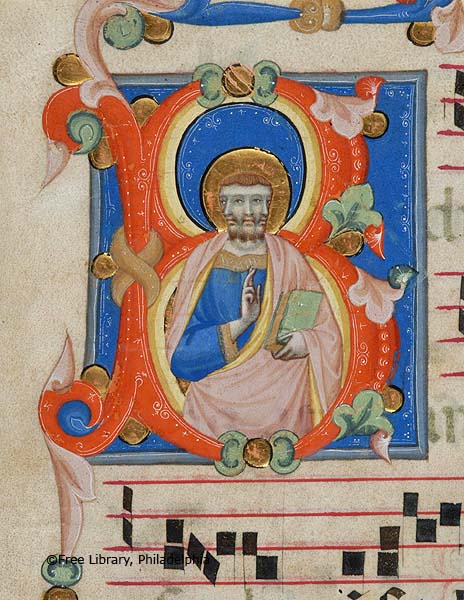

Perhaps you’re looking for a traditional inhabited initial in a musical manuscript, say a representation of the blessing Christ inhabiting the initial B of “Benedictus.” You could of course search for existing images in the traditional way, using the Subject term “Christ, Blessing” or an Associated Text using an incipit like “BENEDICTA SIT….” That could yield a lot of search results! But who wants to comb through those? Let IAI do the job for you, and you could get something like this:

Here, nested cozily in a bright vermilion letter B with all the right kinds of leafy decoration, is a generously robed figure of Christ holding a book as he raises his hand in blessing. Is it perfect? Well… you know how sometimes figures in AI art come out with a couple of extra fingers, or arms, or maybe even faces? Let’s just say we’re still working out a few things.

In the meantime, maybe you’re interested in legendary beasts and looking for a medieval depiction of a fierce mythological animal, say one that uses massive horns and fire to defend itself from attackers. IAI has got you covered! Of course, you could dig around in the Subject Classifications network to see all the different kinds of animals you can actually find in the Index of Medieval Art, maybe checking out the “Mythological and Religious Creatures” category to find your fiery friend. But searching on your own is so old school. Let IAI do it for you! We know you’ll like what you see.

Big horns: check! Fire: check! Attackers repelled: check! Oh wait, you wanted the fire coming from its mouth? How was IAI supposed to know that? Maybe you should have searched on your own for this one, using the Subject term “Dragon.”

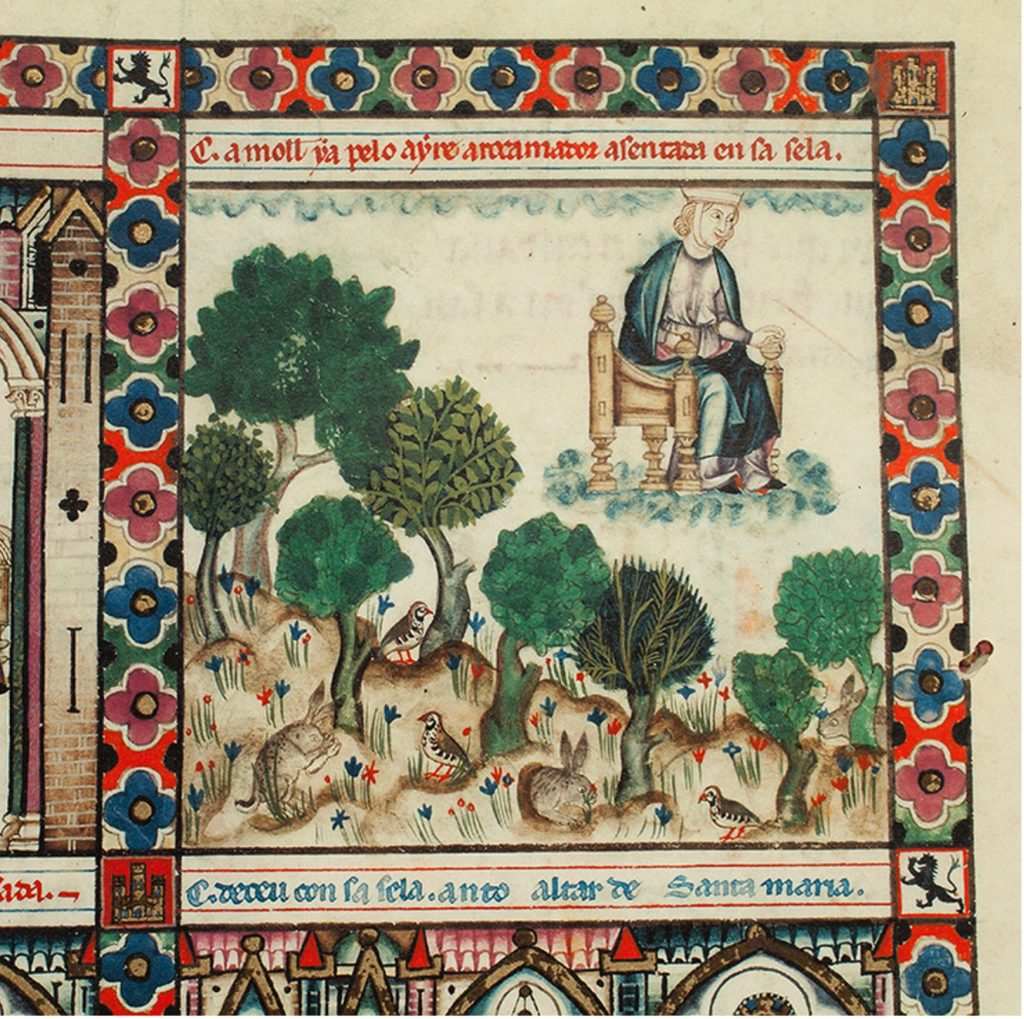

Let’s try something a little simpler. How about a medieval pilgrim? Pilgrimage to sacred sites, whether for penitence or to show devotion, was so important to medieval people that you won’t be surprised to learn there are more than thirty Index Subjects starting with “Pilgrim” in the database. But do you really want to take the time to look at all of those and then have to make decisions about which ones best suit your research needs? IAI has got your back. Let’s make it authentic by narrowing the parameters: we’ll ask for a female pilgrim on her way to the shrine of Our Lady of Rocamadour.

That’s a lady pilgrim all right, and the captions tells you she’s definitely on the way to Rocamadour. Yes, it does seem a little unusual that she’s flying there in a chair instead of riding a donkey, but of course if you’d wanted that kind of detail, you would have used the search filters for a Boolean search of the Subjects “Pilgrim” and “Donkey.” But since when were donkeys so important? IAI thinks this is a terrific way to go. You’ve never heard of armchair travel?

Even if IAI still has a kink or two to work out, we think you’ll love what it can do for you. Mental energy is precious; why devote so much of it to original image research when you can harness multiple terabytes of data and enough electricity per search to fully charge your phone just so IAI can come up with one fantastic image like these? Is IAI easy? You bet. Is IAI fun? Tell us, who doesn’t love flying chairs and flaming poo? Is IAI responsible? Now why would you ask us that? It’s not a self-driving car.

The Index is pleased to announce the launch of a new digital resource for the study of Byzantine iconography, the Lois Drewer Calendar of Saints in Byzantine Manuscripts and Frescoes. Compiled by the late Lois Drewer, PhD, longtime specialist in Byzantine art at the Index, this calendar identifies saints, cites standard and hagiographic references (with a guide to their abbreviations), and concisely describes manuscript illuminations and frescoes. The calendar is organized by feast days in the Constantinopolitan calendar.

There are four main ways to browse the resource. The first is by selecting a month and day under the tab for calendar. This entry point leads to the core of the data, and we recommend this as a good place to start. For example, searching today’s date of the fifth of March reveals three entries for saints: 1. Mark of Egypt; 2. Conon the Gardner; and 3. Hypatius of Gangra. The list you will find there offers identifications, references, and examples.

Many of the saints and holy martyrs included in Dr. Drewer’s calendar are obscure or infrequently represented in medieval art, such as Conon the Gardener (also known as Conon of Perga), a gardener from Nazareth martyred under the Roman emperor Decius (r. 249–251 CE).[1] In some cases, the iconography has not yet been cataloged by the Index, making this an especially useful additional resource.

There are also two lists for iconographic motifs and iconographic scenes with feast days linked on the right, and a list of feasts days organized A to Z. The iconographic motifs and scenes are grouped alphabetically beneath bold headings.

A majority of the headings in this resource cover martyrdom and torture scenes for Byzantine saints–among them holy martyrs, hermits, prophets, and women, but Drewer also included groups for various vestments and clothing, human gestures, attributes, and objects. For example, it is possible to see that an axe is associated with John the Baptist.

In some examples of medieval iconography, the preaching John the Baptist is depicted pointing to an axe at the base of a tree, a reference to Matthew 3:10. Or you can discover that the representation of grief is linked to Sophia of Rome, who is portrayed in various scenes as mournfully throwing out her arms in response to the beheadings of her daughters Pistis, Elpis, and Agape.

There is much to discover by browsing these lists, and we expect that this resource may usefully supplement your searches within the wider Index of Medieval Art Database. You may also try browsing the Svetlana Tomeković Database of Byzantine Art for similar themes represented in Byzantine art. We welcome your feedback, and we look forward to receiving questions through our research inquiries form.

We warmly thank the Index’s Technology Manager Jon Niola for bringing this project to fruition. Lois Drewer dedicated much of her life to iconographic research, and we feel certain that she would have approved of this posthumous tribute. We are proud to offer this additional resource so that all may benefit from Dr. Drewer’s calendar of saints.

[1] Drewer’s database notes three instances of the iconography of the holy martyr Conon the Gardener: a small illustrated Menologion, 1322-1340 (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. f. 1, fol. 30v), and two frescoes in the south aisle of the narthex in Dečani and in the dome of the south tower narthex in Treskavec, all of which have yet to be added to the Index database.

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and we warmly thank Herbert Kessler, Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins University and Index friend, for his time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

After studying medieval art as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, I completed the MFA and Ph.D. at Princeton. At UC, Margaret Rickert had inspired me to become a medievalist; she was also Rosalie B. Green’s Doktormutter, so Rosalie and I had a special bond from the start. I continued to use the Index at Dumbarton Oaks when I was a Fellow there in 1965–66 and then, again, when I returned to Princeton as a Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in 1969–70.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

RBG1 oriented all new graduate students, so 1961. The Index was then in the Neo-Gothic Cram wing of the original McCormick Hall. Graduate students had keys and used it steadily, especially as a picture resource. The Index staff felt under-appreciated and with good cause: though RBG and Isa Ragusa were distinguished and consistently professional and helpful they knew that the faculty did not respect them as scholars. When I was being recruited to the University of Chicago faculty in 1965, the Dean offered to acquire a copy of the Index for me (because William Heckscher, who had been offered the position earlier, had asked for one), but nothing came of that. As computers were evolving in the 1980s, the Getty Center hired two young persons to recommend ways in which the Index might be digitized. Things did not go well, and I was sent (from Johns Hopkins) to reconcile the Index staff with the Getty interlopers. During the discussions, we all realized how the new technology might allow the Index to be modified in ways better to serve other disciplines, especially e.g. by refining types of musical instruments, botanical and zoological species, or agricultural implements.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I have never used the Index for teaching and, frankly, cannot remember a single eureka moment while using it (except, of course, finding a picture I did not know).

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I gave papers at Iconography at the Crossroads2 and Romanesque Art.3 Both were very important gatherings and publications.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As recently as twenty years ago, one of my own graduate students brushed away an argument with “That’s only iconography,” “Only” was the operative word there. In the wake of the material turn, decolonial turn, global turn, historiographic turn, experiential turn, the ornamental turn, . . . . , searching for texts that identify medieval subjects is no longer sufficient. And with the Patrologia Latina and other compendia online, it is not even fun. Simply to dismiss iconography, however, is ignorant. As I myself have argued at length in a recent essay, “the interweaving of text and image and the sensual pleasure of [medieval art’s] color and rich materials” was the essence of medieval art.4 Iconography is therefore destined to remain a fundamental instrument for studying it.

Please join us and register for the next virtual database tutorial with the Index on Tuesday, March 25, 2025 from 12:00 – 1:00 pm EST.

Read more about it at this link: https://ima.princeton.edu/index_training/.

As friends and colleagues around the world prepare to celebrate festivals of light, we at the Index wish you all a luminous holiday season and a peaceful, fulfilling New Year.

This year we’re inspired by the global interest in Index resources, which has grown considerably since we ended our yearly database subscription fees in 2023. Our last online database training session saw individual registrations from more than ten different countries, including Australia, Greece, Spain, Ireland, the UK, Italy, China, and Canada. Interchange with this wide network has been a highlight for us.

In 2024, we also offered online database tutorials, hosted classroom visits, and fielded more than one hundred research questions in person and online. Such interaction is at the core of the Index’s long history as a research tool and hub for scholarship in medieval art history. We here offer a selection of the highly varied questions asked of the Index in 2024:

Please continue to stay in touch. Follow us on Facebook and Bluesky; use our Research Inquiries form; and watch our blog for new events in 2025. Next year’s happenings include an online database training session, an Index Wintersession class on writing alternative text for images, the conference session “Breaking the Mirror” at the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, and a fall conference on “Art and Proof in the Ninth Century.” We look forward to sharing these events with you and to supporting your research for many years to come!