The Index of Christian Art is sponsoring two sessions in honor of Adelaide Bennett Hagens at the 52nd International Congress on Medieval Studies, University of Western Michigan, Kalamazoo, MI, May 11-14, 2017.

Image & Meaning in Medieval Manuscripts: Sessions in Honor of Adelaide Bennett Hagens

Session I: Text-Image Dynamics in Medieval Manuscripts

Session II: Signs of Patronage in Medieval Manuscripts

Organizers: Judith Golden and Jessica Savage, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Please see the full call for papers on our website here: https://ima.princeton.edu/conferences/

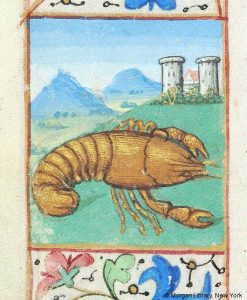

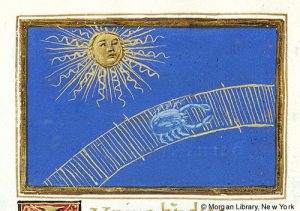

On June 21st we recognize Cancer, the astrological sign that Richard Hinckley Allen called the most “inconspicuous figure of the zodiac” (Allen, 107). Representing the sun at its highest point, Cancer is the zodiacal sign of the summer solstice. In ancient Egypt, the Cancer sign was imagined as a scarab beetle, and in Mesopotamia as a turtle or tortoise, both of which may have pushed the sun across the heavens. In Europe, traditionally, the constellation of Cancer was identified with the crab from Greek mythology that was crushed by the foot of Hercules and placed in the sky by Hera. Some have speculated that the characteristic sideways walk of hard-shelled crustaceans, whether crayfish or crab, could be symbolic of the backward shift in day-length after the arrival of the summer constellation in the Northern Hemisphere at the end of June, and Medieval people also believed those born under Cancer’s influence harnessed great, gripping power.

At the Index of Christian Art, the label “lobster-like” has been used to describe Cancerian crabs that are not at all “crab-like.” These crustaceans have elongated pincers, chunky claws, and a distinct tail, and they more closely resemble a lobster or a crayfish. The zoological treatise The Crustacea, published by Brill in 2004, states that, although crabs are the most frequent symbol of the Cancer sign, that the variety of shellfish that adorn horoscopes “can bring surprises” (Forest et al., 173). It is possible that while the symbol of Cancer may draw from a singular iconographic entity which included all shellfish, the idea of a distinct crab, including its spoken and written labels, could be historically transmutable. A definitive explanation for the choice of crustacean in horoscopes might be impossible, but there are some hints as to why “lobster-like” crabs were so pervasive in zodiacal art of the medieval period.

“Cancer,” “Crab,” & “Crayfish”

“Cancer” is an ancient word of Indo-European origin from a root meaning “to scratch.” Today Cancer is the scientific Latin genus name for “crab,” but in classical usage it described many species of shellfish. J.-Ö. Swahn notes in “The Cultural History of Crayfish” that in both Sanskrit and Greek the word for crab had the same meaning as crayfish, both animals having pincers. While the Latin word for Cancer, Carcinus, comes from the Greek karkinos, the English word “crab” has Germanic and Old English roots, and an Anglo-Saxon chronicle from about the year 1000 identified Cancer as crabba (Allen 107). In Old High German (800-1050), kerbiz meant simply “edible crustacean” and was also used to describe crayfish. The OED links the Middle High German (1050-1350) krebz to the Middle French (ca. 1400-1600) escrevisse, which in turn became écrevisse (crayfish).

The OED cites these words for crayfish, through much of their history, were general terms for all larger edible crustaceans. On “lobster,” OED notes some crayfish are called “fresh-water lobsters” and the term “lobster” is applied to several crustaceans of resemblance. Well into the seventeenth century, the word “cancer” and its translations were used as generic terms for all crabs and “lobster-like” creatures until Linnaeus established the species name Astacus Astacus for crayfish in his Systema Naturae of 1758 (interestingly, also with the synonym Cancer Astacus). The OED also noting that the 1656 translation of Comenius’ Latinae Linguae Janua Reserata, described the crayfish as a “shelled swimmer, with ten feet, and two claws: among which are huge Lobsters of three cubits; round Crabs; Craw-fish, little Lobsters.” So, etymologically speaking, crabs, crayfishes, and lobsters were mingled together from very early on.

Star Sign and Sustenance

In the Middle Ages, the zodiacal symbol of Cancer often appeared in the calendar pages of devotional books, or on adorned monumental sculpture of the Middle Ages. The Index records examples in these mediums (including examples on more than 200 manuscript pages) with the subject heading Zodiac Sign: Cancer. Generally, the depiction of the sign of Cancer as a crab is most prevalent in art from the Mediterranean and Western Europe, possibly due to the proximity to the sea, but the crayfish as a symbol for Cancer is not unusual, even in coastal regions. Crabs are saltwater decapods, creatures with ten feet or five pairs of legs. Crayfish are also decapods, but they thrive in freshwater lakes and rivers. Summer was the best season for fishing, and crayfish were easily trapped along the streams and creeks of rural Europe. The French and the English were the first to incorporate crayfish into their diet.

The Romans had viewed the crayfish as a scavenger animal, and they disliked the taste in their cuisine. Elevated from its lowly status as mere fodder in the classical era, crayfish came to be considered a delicacy in Western Europe from as early as the tenth century. In medicine, the sign ruled over the chest, stomach and ribs, and there are also several medieval pharmacological texts that note the medical properties of the crayfish, including the fact that “If you boil them in milk they cause a good sleep” (Swahn, “The Cultural History of Crayfish,” 247). We know that Europeans were using crayfish in their recipes and tinctures, so their distinctive form would have been a familiar one.

Sources

Allen, Richard Hinckley, Star-names and Their Meanings (New York, Leipzig: G.E. Stechert, 1899), 107-111.

Fischof, Iris, “The Twelve Signs,” in Written in the Stars: Art and Symbolism of the Zodiac (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 2001), 111.

Forest, Jacques, J. C. von Vaupel Klein, and J. Chaigneau, The Crustacea: Treatise on zoology – anatomy, taxonomy, biology: Revised and updated from the Traité de zoologie (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 173.

Larkin, Deirdre, “Making Hay: The Zodiacal Sign of Cancer,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Blog, June 5, 2009, http://blog.metmuseum.org/cloistersgardens/2009/06/05/making-hay/060509_bottom/

Swahn, J.-Ö, “The Cultural History of Crayfish,” Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture 372-373 (2004): 243-251.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Cancer,” “Crab,” “Crayfish,” “Lobster,” accessed June 2016, http://www.oed.com/.

“Summer and Crayfish,” The Medieval Histories Blog, June 15, 2016, http://www.medievalhistories.com/summer-and-crayfish/.

Reminiscences of Summer Holidays in France

To welcome summer, the Index of Christian Art presents an exhibit of travel ephemera from various cities in France. This selection of guidebooks and maps from the Index archive was inspired by a summer road trip to some of our favorite destinations, including Amiens, Tours, Bourges, Strasbourg, Beauvais, Dieppe, Toulouse, Chantilly, Beaune, Aigues-Morte, and NÎmes. Marked with the pencil signature of Rosalie Green, Index director from 1951 to 1982, many of these guidebooks and maps seem to have been used by Indexers researching cities with important monuments and museums relevant to the mission of the Index.

Guidebook of Chartres, “its Cathedral and Monuments,” by Alexandre Clerval (1859-1918) published in Chartres in 1926. Alexandre Clerval was a Chartrian priest who first wrote an important doctoral thesis on the School of Chartres in 1895.

Preserved in their original printed wrappers, these guidebooks provided details about places of interest to tourists and scholars alike. Perhaps Indexers used these very maps and books to plan an itinerary of sights and sites in all these cities. Mostly in French, and retaining period advertisements, the material here dates from the 1920s through 40s. The unfolded map of Strasbourg is from a Rapide-Plan printed by J. Finck in 1946. Although intended to accompany a traveler on the go, these pocket-sized guidebooks are also treasured by anyone who enjoys armchair travel to distant shores or a lazy summer day lost in remembrance of things past.

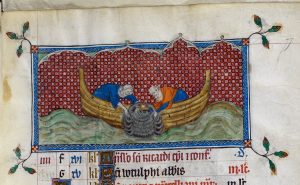

The Index of Christian Art presents three images in honor of the 160,000 allied troops who landed on the fortified beaches of Normandy on 6 June 1944. The first, a detail of the Bayeux Embroidery portraying Duke William of Normandy sailing to England, evokes the seaborne operation that marked the beginning of the liberation of occupied Europe from Nazi control. The second, a sculpted personification of Fortitude holding a sword and shield from the west façade of Notre-Dame of Paris, speaks to the courage and resilience of the allied forces in the face of the enemy. The third, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s languid depiction of Peace from the Allegory of Good Government fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, alludes to the aftermath of the war, while also expressing hope for the resolution of current conflicts worldwide.

Mother’s Day has been celebrated annually in the United States on the second Sunday in May for over one hundred years. Following its declaration as an official holiday by the state of West Virginia, Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation announcing the first national Mother’s Day on 9 May 1914.

Images of the Virgin and Child are among the most common depictions of motherhood from the Middle Ages. The Strahov Madonna of ca. 1340 captures the dynamism (or “squirminess”) typical of small children, while also communicating to beholders the special status of the figures through solemn expressions and meaningful gestures. The Child grasps his mother’s veil with his left hand and holds a goldfinch in his right hand, a pose adapted from the Virgin Kykkotissa, a highly venerated, miracle-working Byzantine icon thought to have been painted from life by Saint Luke. Portrayals of the Visitation present an earlier stage of motherhood.

A fifteenth-century French Book of Hours shows the pregnant Virgin gently cradling her swollen abdomen as she greets her cousin Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist, who “leaped in her womb” (Luke 1:41). A thirteenth-century fresco of the birth of John the Baptist from Parma Baptistery captures yet another aspect of motherhood, depicting two midwives tending to Elizabeth as two others bathe her newborn infant.

The Index of Christian Art has 29 subject records for the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. John the Baptist: Birth appears in 104 records.

The Index will be represented at two events at the Medieval Congress at Kalamazoo this year. First is a joint reception with the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence at 5:15 pm on Friday, May 13, in Bernhard 208. Second will be two sessions, titled “Pardon Our Dust: Reassessing Iconography at the Index of Christian Art,” organized and chaired by Index researchers Catherine Fernandez and Henry Schilb, on Sunday from 8:30 to noon in 1145 Schneider Hall. We hope to see many friends there!

Detail of Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent. Old Testament Picture Book. French, c. 1250. Morgan Library, M.638, fol. 8r

Nine times Moses went to the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II to demand freedom for the Israelites in captivity, saying “Let my people go.” Each time Moses and his brother Aaron were sent a way, an episode classified by the Index as, Moses and Aaron: driven from Pharaoh’s Presence. Despite these increasingly tense exchanges, and then a marvelous act that changed Aaron’s rod into a serpent before the Pharaoh’s court (Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent), Ramses still refused to release the Israelites from slavery.

What followed was the foretold wrath of God enacted as ten crippling plagues on the Egyptians. In the first wave of calamities, there were plagues of blood, frogs, gnats, and lice that polluted the air and water. The second wave, brought plagues of flies, diseased livestock, and boils. Then came hail, locusts, and darkness that fell on Egypt for three days. The tenth and final plague, the “Plague of the Firstborn,” claimed the lives of the eldest children in all Egyptian families. The Index of Christian Art classifies the subjects of the Exodus plagues under the major figure of Moses:

Moses: Plagues of Flies, Frogs, Locusts, Hail and Pestilence. Stuttgart Psalter, c. 820-830. Stuttgart Landesbibliothek, Bibl.fol.23, fol. 93r. Photograph by Gabriel Millet.

(Exodus 9:6-7)

The final plague is described in several phases throughout the books of Exodus (11:4-8; 12:1-13, 21-23, 29-30). Moses first warns of its coming to the embattled Ramses, but his warning is dismissed.

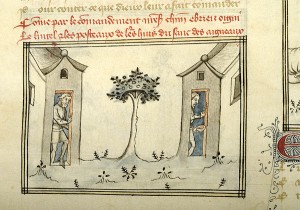

Facing the impending deadly plague, Moses instructs the Israelites to make a sacrificial offering to God, and to use the blood of the animal – a male yearling – to mark the doorposts and lintels of their homes. Moses explains to them that marking their homes this way will spare their firstborn children from the “death angel,” saying he “will pass over the door.” (Exodus 12:23).

Moses: Plague of Firstborn. Two Israelites marking the doorposts and lintels of their homes with the blood of the sacrificial lamb. History Bible, Paris, c. 1390. Morgan Library, M.526, fol. 14v

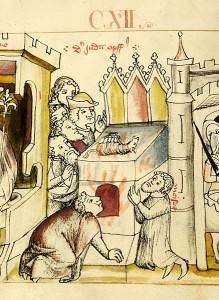

Detail of Moses: Passover. Israelites cooking the sacrificial lamb under the inscription “Die Juden Opffer.” Historien Bibel, Swabia, late 14c. Morgan Library, M.268, fol. 7v

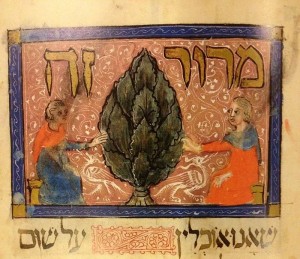

Following this, the Israelites were delivered from bondage and departed from Egypt. The Exodus is remembered at the feast of Passover – the Hebrew feast of Pesach – with special instructions for preparing, eating, and storing traditional, often symbolic food. While Passover traditions have varied over time and from one region to another, it is generally a family holiday in which the meal is accompanied by readings, songs, and traditional rituals designed to remind the celebrants of the Exodus story and the hopes for a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. The order of the seder, or Passover meal, is set out in a book known as the Haggadah, which was sometimes richly illuminated in the Middle Ages, as shown here in the Sarajevo Haggadah, originating in Barcelona in the middle of the 14th century. Well-known related manuscripts to this Haggadah include the Rylands Haggadah and the Simeon Haggadah. The Index classifies subjects depicting the original Passover feast as Moses: Passover, Moses: Passover proclaimed, and Moses: Law, Feast of Passover and with a general heading for Scene: Passover.

Bitter herb or “maror” in the Sarajevo Haggadah. Barcelona, c. 1350. Sarajevo, National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photograph Wikimedia Commons.

The middle of April strikes dread (or joy) in the hearts of millions of tax filers. Since 1955, April 15 has typically marked the end of the tax season in the continental US. This year, however, filers have received a three-day reprieve to accommodate Emancipation Day in Washington D.C, which is observed on the weekday closest to April 16 when it falls on a weekend.

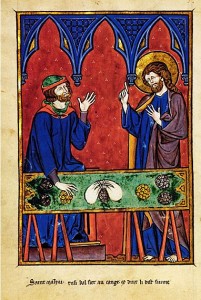

Saint Matthew is among the best-known tax collectors in the history of Christian art. According to the gospel accounts, Jesus encountered Levi (Matthew’s name before his conversion) in the custom house of Capernaum on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. Jesus said to him, “Follow me,” and Matthew obeyed.

A remarkable depiction of Christ calling Matthew appears in the Picture Book of Madame Marie, a thirteenth–century French devotional manuscript now at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. The scene takes place beneath sharply-cusped arches and against a fiery background. Wearing a brilliant blue garment and purple cloak, Christ addresses Matthew, whose money table has been dramatically tilted to reveal neat piles of gold and silver coins. Thematically related is a fifth-century gold solidus of Pulcheria with the empress wearing an elaborate coiffure and lavish jewels, a macabre Dance of Death featuring a money-changer from a fifteenth century French Book of Hours, and a regal image of the Queen of Coins on a fifteenth-century Italian tarot card.

May the rocks in your field turn to gold!

Heartfelt thanks to the over 150 people who took our online survey this past month. Your thoughtful, detailed responses will be central to our plans for the coming year. They confirmed many concerns already on the mind of Index staff, especially concerning the difficulties of navigating our current database. They resolved a few hot office debates over how researchers approach the system (Team “Keyword Search” routed Team “Browse List,” 93-7, while “Search by Subject” ran away with “Initial Search Field,” earning 87% of responses). They also offered high marks for the accuracy of our data and the quality of our programs and publications. Most appreciated of all, however, were your concrete, insightful suggestions about how the new database could be designed so as to perform most effectively for an evolving scholarly community.

Heartfelt thanks to the over 150 people who took our online survey this past month. Your thoughtful, detailed responses will be central to our plans for the coming year. They confirmed many concerns already on the mind of Index staff, especially concerning the difficulties of navigating our current database. They resolved a few hot office debates over how researchers approach the system (Team “Keyword Search” routed Team “Browse List,” 93-7, while “Search by Subject” ran away with “Initial Search Field,” earning 87% of responses). They also offered high marks for the accuracy of our data and the quality of our programs and publications. Most appreciated of all, however, were your concrete, insightful suggestions about how the new database could be designed so as to perform most effectively for an evolving scholarly community.

Three issues emerged repeatedly in the survey results. First was navigation: many researchers reported difficulty using the online database because of outdated or unwieldy design, unfamiliar terminology, and a lack of research guidelines. Close behind this was cost: past subscription fees for the Index have been high enough to make access difficult for smaller institutions and individuals. Finally, many researchers expressed concern about access to and quality of images: not only did past policies at the Index restrict many images from view by remote users, but the quality of our older images (some nearly a century old) can be quite low.

We hear you, and we are happy to say that most of these issues should be mitigated as we move to a new database design over the next two years. We are currently engaged in selecting a vendor to create the new system, which will be more intuitive, researcher-oriented, and image-centered than the original 25-year-old design. We also expect it to be more efficient, allowing us to migrate existing data and integrate new material, including improved images, with greater speed and effectiveness, while nationally changing practices surrounding copyright and fair use will allow us to make more of those images available universally. Finally, once a vendor is selected and the database is in design, we will address the question of subscription costs with our advisory committee, with the goal of offering more affordable access to the database for both institutions and individuals, including independent scholars and students.

We look forward to sharing news of all the changes to come at the Index as we approach our 100th year, and as always, we look forward to hearing from you when our resources or research staff can be of help to your work.

Words and Deeds of Charles Rufus Morey at the American Embassy in Rome (1945-1950)

Charles Rufus Morey, founder of the Index of Christian Art, was the first to fulfill the role of American cultural attaché to Italy, a tenure beginning with his retirement from Princeton University’s Department of Art and Archaeology in 1945. A champion of Italian culture, Morey’s mission at the American Embassy in Rome not only promoted Italian national heritage but reconstructed it after the ravages of world war. Morey’s distinguished background in classics and art history, coupled with his longstanding ties to the study of historical Rome, made his assignment all the more fitting.

As a diplomat, Morey actively sought opportunities to repatriate books and works of art looted in wartime Europe and he created the Union of Archaeological and Historical Institutes to safeguard artifacts in transit. Two of his notable publications while in Rome were, “The War and Medieval Art,” College Art Journal, IV, 1945, and “Saving Europe’s Art,” Journal of the American Institute of Architects, III, 1945. Among his main activities were the establishment and maintenance of research libraries in Italy. Morey oversaw the direction of the American Academy in Rome from 1945 to 1947, where he brought in major speakers, lectured widely, and organized exhibitions which increased Italian–American cultural exchange. He formed many collegial relationships with important people, among them nobles, curators, and clerics, who knew him as Professore. Pictured here from the Index archive is a photographic postcard dated 1948 of Morey with Prince Don Giovanni Francesco Alliata di Montereale, President of the Nato-American Association, while they walk together in Segesta, Sicily.

The Index is fortunate to house a wealth of materials associated with Morey during his time in the Foreign Service. Through these items, we wish to show a different facet of the founder of the Index, whose words and deeds as a cultural attaché to Italy left a lasting mark on this organization. On long-term display in the Index is a collection of Morey’s prize medals given to him on various occasions, including one from Pope Pius XII to commemorate the Jubilee year in 1950.

This exhibition was planned to accompany the 25-26 March 2016 Symposium of the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence, “Words and Deeds: Actions Enacted, Re-Enacted & Restored.” These materials will be on view until 31 May 2016.