June, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc du Berry (Chantilly, Musée Condé, 65/1284), fol. 6v © Photo. R.M.N. / R.-G. Ojda

The Index will be closed on June 4 and 5 as Princeton celebrates Class Day and Commencement 2018. We look forward to welcoming visitors during Princeton University weekday summer hours, 8:45-4:30, beginning June 6.

Second in a series of short blog posts introducing new features of our online database

Have you tried our Language Filter yet? Since we at the Index of Medieval Art realize that some of the search features available to users of the new database may be unfamiliar, we thought that we ought to take some time to recommend and explain a few of them. This time, let’s discuss your use of language, shall we? Specifically, did you know that you can filter your searches to look for images that appear in the context of a certain language? Well, you can!

Say you’re interested in images of Joseph of Arimathea, for example, whether in a scene—such as the Deposition or the Entombment—or as an isolated figure. You might start with a simple keyword search for “Arimathea” on the database homepage, or you could also use the “Terms” tab on the “Advanced Search” page, checking “Description” and “Subject” in the “Search Fields” checklist, a strategy that currently yields a whopping 735 results.

Now let’s try using one of the filters. Simply switch to the “Filters” tab on the “Advanced Search” page. Feel free to explore, and try all or any of the filters. For the purposes of this demonstration, however, we’re thinking about language, so let’s start by narrowing our search to manuscripts. Simply select “Manuscript” in the Work of Art Type Filter (Example 1), then click “Search” again. You’ll discover that, in this case, you have nearly halved the search results to 373, but that’s still a lot of records to consider.

Now here comes the exciting part! If you know that you’re interested in a particular linguistic context, then you can add the Language Filter to your Advanced Search. There are currently 48 languages to choose from in the Index of Medieval Art database. For this demonstration, we’ve specified Greek (Example 2), so we’re searching for the word “Arimathea” where it appears in either the Subject field or the Description field, only in records for which the Work of Art Type is “Manuscript” and the language of the manuscript is “Greek.” Click “Search,” and you’ll discover that you have been able to filter your results down to a manageable 32 records!

Simple, n’est-ce pas?

You can easily change the Language filter to compare results from one language to another. Changing Greek to Armenian yields ten results. Church Slavonic yields six. Filtering for some languages may return nothing, others quite a lot. Latin, for example, returns 233 results, so you might want to add another filter to your search. For the time being, only the languages of manuscripts are identified in the database. Eventually, however, the Index database will identify the language or languages of every object that incorporates the written word.

You might have noticed that names of some languages include date ranges, as in “Middle English (1100–1500).” Although such dates can seem arbitrary, we try to differentiate among the stages of a language’s development. If you’re curious about how the Index defines a language, or about what sources we cite, you can click on the language name in the Language field of a Work of Art record. This will take you to a page where you can read the Language Details. There you’ll also find citations and external reference codes (Glottolog and ISO 639-3). On that page, there is also a list of all Work of Art References that include that language.

So, start exploring, and be sure to try out the filters available in the new Index of Medieval Art database. Also, please let us know what you think…but mind your language!

First in a series of short blog posts introducing the new features of our online database

Did you know that you can search The Index of Medieval Art for information about patrons of medieval art? The Index records both identified and unidentified patrons, the latter entered as grouping terms for types of patrons (Male, Female, Couple) and major monastic orders, such as Augustinian, Benedictine, and Carmelite. There are also general headings for anonymous male and female patrons (Male, unidentified and Female, unidentified). Names of churches, monasteries, and abbeys are given by their proper titles, such as Canterbury Cathedral, but might be further identified by location (e.g. Abbaye d’Anchin [Pecquencourt, France]).

For an overview of our patron headings, click on Browse at the top of the Index landing page. This will bring you to a list of over 900 names and grouping terms sorted in alphabetical order. To reach a specific entry, type the first few letters of a name into the search line at the top of the list. For instance, typing in “Blanche” will bring you to all Blanches from Burgundy, Castile, France, Navarre, and also the late 14th-century Countess of Geneva. Clicking on any patron heading will return a glossary entry comprising a biographical note with dates, alternate names of the patron, a bibliographic citation, an external reference for the authority source, and all the work of art examples linked to that patron.

Our patron entries are formatted in keeping with standard biographical authorities, such as the Library of Congress Name Authority File, the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), and Oxford References. Patrons are identified in the Index database by their roles and dates when these are known. When performing an Advanced Search in the “Terms” screen, you may prefer to keep the Match Type set to “Default,” which will search all parts of the heading. In the “Terms” window, a search can be formulated with keywords such as “Pope,” “Doge,” or “Prince,” using “Patron” in Search Fields to locate medieval patrons by their role. Similar keywords, along with keywords for place indicators like “Monastery” or “Convent,” can be searched against the “Patron Note” field, which will search the biographical notes in the patron glossary.

Many of the monastic patrons contain their locations in parentheses after the name of the community, so countries of patronage activity can also be searched as keywords. For instance, searching against “Patron” or “Patron Notes” with the keyword “Italy” returns over 150 records. This indicates artwork results for a patron who was active in Italy. From here, in the “Filters” window, the Date Slider can be used to refine results. The “Terms” search can be refined with any of the additional filters, including “Location,” “Medium,” “Style/ Culture,” and “Work of Art Type.”

Are you interested in finding out which female patrons were active in France in the 14th century?

In the Advanced Search “Terms” screen, enter the keyword “Female” and choose the Search Field “Patron” (keeping Match Type set to “Default,” as recommended).

Then, go to “Filters,” select “France” as a Location, and set the Date Slider to 1300 and 1399. This search should yield 27 examples, where a female patron is connected to the 14th century work made in any part of France.

*In results, please note that work of art records will include Main records indicated with a logo picture.

As you search for patrons in the new Index of Medieval Art database, bear in mind that visual representations of patrons are found in the Subject field. To find images of patrons, you can browse or search the Subject field with the keyword “Donor.” To read more about medieval patronage practices in general, you might find the Index’s 2013 conference publication Patronage, Power, and Agency in Medieval Art of interest. Enjoy refining your searches and browsing the range of patrons we record in the Index! And please remember that we are always happy to have your feedback. Get in touch with us at theindex@princeton.edu.

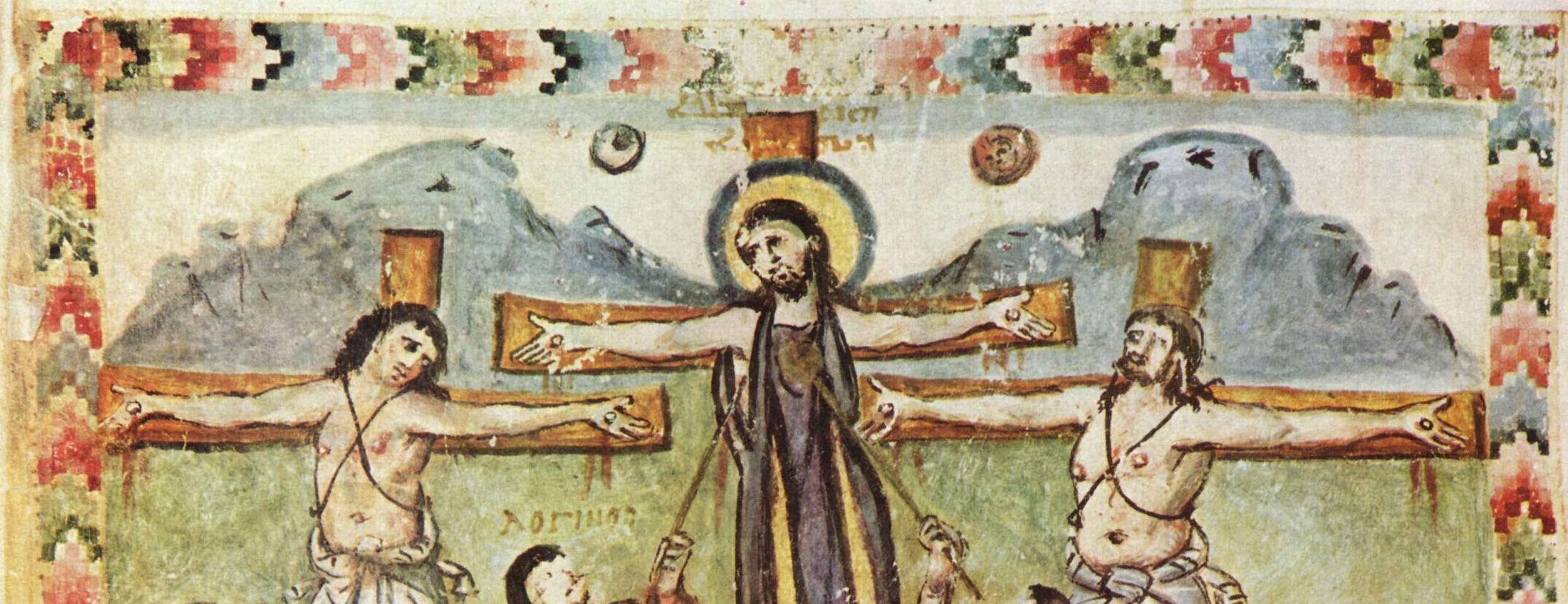

Matthew’s Gospel tells us that, at the moment Christ died, darkness swept over the land for three hours (Matthew 27:45). The foreboding skies at Christ’s crucifixion were also recorded in Luke 23:44-45 and Mark 15:33. Mark’s account, thought to have been written around the year 70 CE, was likely the earliest.[1] Some scholars have reasoned that this midday phenomenon was an actual eclipse, because the passage in Luke reports that darkness fell over the land when “the sun was eclipsed” (“τοῦ ἡλίου ἐκλιπόντος”) (Luke 23:45). However, the passage is usually translated “the sun was darkened.” The verb is in the passive voice, as is the verb “ἐσκοτίσθη” used in other versions of the Greek text, and both words can mean “was darkened” or “was obscured.”[2] No matter how we may interpret the words relating the phenomenon, and no matter whether it is possible to attribute the darkness thus described to a real astronomical event, scriptural hours of daytime darkness over Golgotha presented an iconographic opportunity to medieval artists depicting the Crucifixion.

In manuscripts and painted works of art that aimed to depict the event, color was frequently exploited to illustrate darkness and to create a dramatic setting. Across media, the celestial bodies of the sun and the moon were incorporated into the skies above the crucifixion, not only to signal darkness at daytime but also to imbue the scenes with a rich cosmological significance.

An especially early example appears in the Syriac Rabbula Gospels from the late sixth century. In this manuscript, the Crucifixion includes a partly eclipsed Sun and a Moon with a face against a remarkably light sky; a sliver of shaded pigment at the top suggests darkness (Figure 1). From antiquity, the sun and moon were associated with power. In early medieval crucifixion scenes they represented God’s cosmic anger at the death of Christ.[3] Throughout the Middle Ages, personifications of the Sun and Moon became regular characters at the Crucifixion, positioned as sorrowful figures mourning Christ’s death. The placement of the Sun and Moon respectively at the right and left arms of the cross came to be read typologically as the Old and New Testaments.[4] After about 850, they could also be seen as allegorical representations of Church and Synagogue.[5]

The Ottonian Sacramentary of Henry II sets the Crucifixion scene against a deep purple background, a striking hue used to set a somber mood and suggest darkness (Figure 2). Busts of the personifications Sun and Moon sit on the arms of the cross. The Sun, labeled SOL and sporting a rayed headpiece, and the veiled Moon, labeled LUNA, both turn away from the scene and weep into their draped hands. The strong background color effectively conveys the darkness of this scene emphasized by the dramatic gestures of the Sun and Moon.

Medieval artists sometimes set the same iconographic features within a flattened space of gold or patterned backgrounds. A leaf from the Potocki Psalter, made in Paris in the mid-13th century, sets the Crucifixion against a gold background (Figure 3). Christ is flanked above by the sun and moon and below by the Virgin Mary and the Evangelist John. Within this composition, the three main figures hover between time and space, darkness suggested only by the presence of the partly obscured sun and the crescent moon.

Similarly, in a Crucifixion scene painted around 1400 to 1410 in a Register of Coiners and Minters from Avignon, a richly patterned background of gold scrolls avoids any illusion of a dim sky (Figure 4). The red sun and the moon’s countenance in the upper corners of the miniature are the only clues that the ornamental ground is actually simulated “darkness.” In both miniatures, decorative and luminous backgrounds highlight the central features of the scene so that the Crucifixion image becomes a place of mediation, the background “darkness” metaphorically positioned between an earthly space and a shift in the cosmos at the moment of Christ’s death.

Images of darkness at the Crucifixion can be found in the Index database by any of several possible search strategies. One method is to perform an advanced search using the keyword “Crucifixion” while filtering with the subject “Sun and Moon.” This search returns over 380 results. Executing the search again with the subject “Personification: Sun and Moon” returns around 220 examples in a variety of media, including ivory plaques, glyptics, and frescoes. “Personification: Sun and Moon” is the subject used by the Index for records concerning works on which both celestial bodies have facial features. Using words like “stars” or “starry,” background elements that can also suggest a dark sky may be recorded in the Index’s descriptions of such works.

With the advent of the Index of Medieval Art’s new database, thumbnail images are now visible with search results, allowing the researcher to review works of art at a glance. Thus, a researcher looking into images of the Crucifixion will be able to notice the gradual change in the later medieval period in the West, when images of the Crucifixion began to represent the three-hour darkness as a true night sky. In a Book of Hours made in Paris about 1490, a soft pattern of gold stars with the sun and moon dot a dark blue sky to create the illusion of evening (Figure 5). Other Crucifixion scenes that a researcher may notice while thumbnail browsing show cloudy, dark, and emotive skies that convey darkness without the sun or moon. These atmospheric scenes offer a remarkable and naturalistic, if not peaceful, departure from the earlier ones with their grief-stricken personifications of the Sun and Moon.

The starry night sky casts a familiar source of light over a recognizable scene, and these astronomical bodies inspired fascination in medieval minds still forming theories about what those bodies might actually be. Nevertheless, the symbols of the Sun and Moon, while signaling darkness and the passage of time, also imparted emotional weight, persisting in iconography not only to adhere to scriptural tradition, but also to emphasize the significance of Christ’s death.

Further Reading

Hautecoeur, Louis. “Soleil et la lune dans les crucifixions.” Revue archéologique, ser. 5, XIV (1921): 13-32

Schiller, Gertrude. “The Crucifixion.” In vol. 2 of Iconography of Christian Art, 88–164. London: Lund Humphries, 1972.

Nickel, Helmut. “The Sun, the Moon, and an Eclipse: Observations on The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, by Hendrick Ter Brugghen.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 42 (2007): 121–24.

[1] The Gospels report three other supernatural events that occurred during the Crucifixion: the temple veil was split in two; various earthquakes shook the land; and the souls of the dead rose from their graves. See related subjects in the Index of Medieval Art: Christ: Crucifixion, Earthquake; Christ: Crucifixion, Resurrection of Dead, and Veil of Temple: rending.

[2] Bible Translation. “David Robert Palmer trans., The Gospel of Luke: Part of The Holy Bible.” Accessed 30 March 2018. Bibletranslation.ws/trans/lukewgrk.pdf. See especially p. 116, n. 307.

[3] Gertrude Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, trans. Janet Seligman (London: Lund Humphries, 1972), 2:94.

[4] This interpretation was promoted by St. Augustine (354–430 CE). Schiller, 109.

[5] Schiller, 110.

It’s easy to assume that medieval iconography was unchanging: that after a particular way of representing a saint or scene was invented, it became fixed in tradition. Not so! Medieval iconography and the stories that lay behind it moved constantly with the times, adapting over the centuries to the local beliefs and practices of their surrounding communities. Many of these post-medieval adaptations were frankly anachronistic, as is the topic of the present post, which also happens to be of central importance here at the Index: coffee.

Coffee was not a medieval beverage; the earliest evidence of its consumption in this form derives from fifteenth-century Yemen, from where it spread to other parts of the Islamic world, reaching Ottoman-ruled Constantinople in the sixteenth century and western Europe soon after. Where it was traded most actively, it inspired import companies, coffeehouses, and coffee-centered social practices, eventually even percolating (!) into medieval artistic and legendary traditions to which it had no original connections at all.

One example of this trend is Saint George’s “coffee boy,” a name sometimes given to the small figure holding a vessel who rides behind the saint on certain Byzantine and “post-Byzantine” icons (Fig.1). The type for some time puzzled scholars, who now conclude, on the basis of written sources, that such scenes depict Saint George miraculously rescuing a Christian captive.

However, the path to this conclusion was once obscured by alternative local interpretations. One legend that still circulates today in some villages in Cyprus explains that Saint George was drinking coffee when news reached him of the princess he was to rescue from a dragon. With no further ado he mounted his horse, and the coffee boy immediately followed him with his beverage, allowing the saint to finish it on the ride. While the legend seems unlikely (to say the least), our interest lies in how this conflation came into being. Why would the explanation of this image rest on coffee, a beverage unknown either to the third-century saint or to the medieval icon painters who portrayed him?

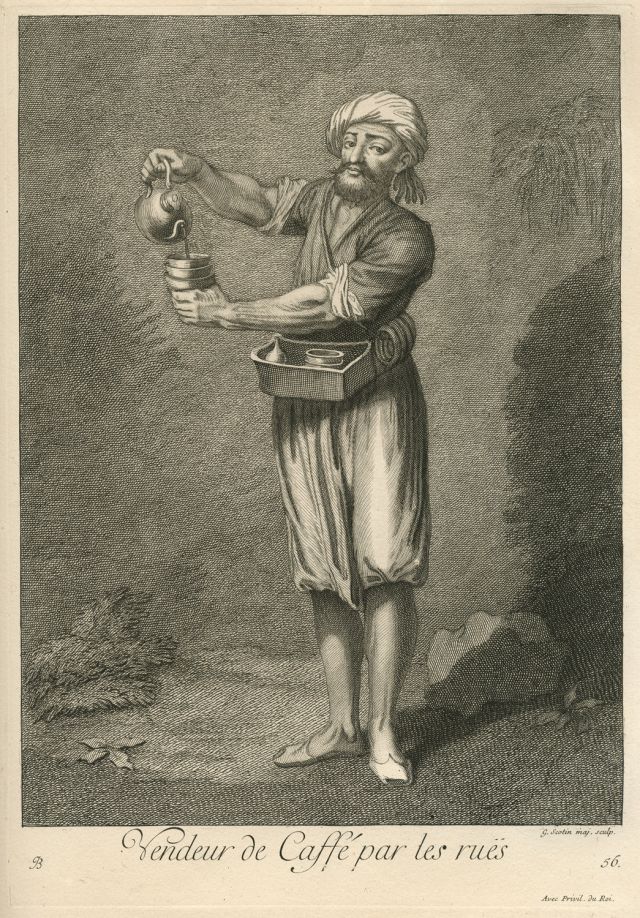

To answer this, we must return to the two original legends that inspired this iconography. In the former, the young boy was captured by the Bulgarians. He was so handsome that their ruler made him a steward and kept the boy in his residence. On the same evening Saint George rescued him, the ruler had asked him to bring water for hand-washing during the supper in the palace. In the second instance, the boy was taken into captivity by the Saracens and was made the personal cupbearer of the Emir of Crete; he was in the act of offering a glass of wine to the Emir when Saint George appeared and rescued him. The first representations of this iconography, in which the boy holds either a cup or a ewer, appeared in the twelfth century and then spread in the Eastern Mediterranean, where they promoted the role of Saint George as defender of Christians in areas threatened by foreign invasion. Not surprisingly, the type became even more widespread in Orthodox icons after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Ottoman Empire.

In this later period, the representation of the miracle of the captive boy was often conflated with the more famous episode of Saint George killing the dragon and saving the princess (Fig. 2). This compositional transition combines the two miraculous episodes to reinforce the original connotation of protection from “infidels,” embodied by the young boy, and of the fight against evil, symbolized by the dragon and the unharmed princess. After the sixteenth century, the garments worn by the young boy reflect contemporary fashion under the Ottoman rule: baggy trousers, a yelek (vest), a cebken (jacket) and a distinctive hat. The opacity of the ewer he holds, which resembled a coffee pot, may have led to the boy’s identification as a coffee server, much like the vendors found throughout Ottoman-ruled lands (Fig.3). Like so much medieval iconography, the interpretation of St. George’s “coffee” boy thus tells us much more about the preoccupations of a changing early modern society than it does about George’s own hagiography.

The association of coffee with St. Drogo, a French saint venerated at Sebourg, has even more circuitous history. Since about 1860, Drogo has been credited as the patron saint of coffeehouses, especially in Ghent, but the reasons for this remain obscure. A twelfth-century orphan, he early devoted himself to penance, pilgrimage, and charity, giving away all that he earned as a shepherd beside what he needed to stay alive (Fig. 4). When a painful hernia made work and travel impossible, he settled down as a hermit in Sebourg, living on a bare ration of brown bread and warm water until his death in 1186.

Drogo’s hagiography offers nothing that might link the saint to coffee besides his penchant for drinking warm water, and this might have encouraged his association with the beverage. However, it may be worth considering that in the mid-nineteenth century, when the saint’s link to coffeehouses is first recorded, his cult center of Sebourg was also renowned for the production of chicory, a plant used in combination with coffee and as a coffee substitute in both France and the Low Countries from the late eighteenth century onward. Could the local chicory trade have encouraged St. Drogo’s association with coffee drinking? We would love to hear from historians who may have an answer to this mystery.

Anachronisms aside, what St. Drogo and the “coffee boy” tell us quite clearly is how flexibly saints’ lives and iconography responded to the changing priorities of the communities around them. The same flexibility more recently has given us Saint Claire as the patron saint of television and Saint Isidore of Seville as patron of the internet. What new saintly protectors will the 21st century bring? There’s a question to ponder over your next cup of joe.

Contributed by Pamela Patton and M. Alessia Rossi.

Isidore of Seville (?) at his desk, from the Stuttgart Psalter (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, MS 23), fol. 1v

As our subscribers will have heard, refinements of the new Index database application are proceeding on schedule, and on March 30 it will become the primary and only route to online search of Index records. We think you’ll find the new platform much more user friendly and appreciate features such as filtered searching, a date slider, and (mirabile dictu) immediately visible thumbnail images.

Subscribing institutions should be switching the URL to https://theindex.princeton.edu, and some may have done so already. You should also be able to access the database by navigating to this URL if you are on site and using the IP range of a subscribing institution.

If you’d like a jump start in using the new system, please check out the tips below. Your feedback is welcome at theindex@princeton.edu.

Follow this link to reach the landing page:

https://theindex.princeton.edu/

Once there, click on the “Search” dropdown and choose “Advanced Search.” Type one or more keywords into the “Search Expression” line for a Boolean search, which can be filtered by Work of Art Type, Creator, Location, etc. in the fields below; dates can be refined using the slider. Exact-phrase searching iis coming in the next few weeks, so if it isn’t active when you visit, please check back.

Clicking the search button calls up a results list that appears below the search filters; click thumbnails to see the full records. Works can also be searched for by browsing the Index authorities for Subject, Creator, Patron, among others; each authority includes an expandable bar containing to the records in which the term appears.

As you try out the site, please remember that some design elements and search tools are still actively in development: layout, terminology, and search dynamics still may change. This makes your feedback all the more useful, as it helps us to evaluate future refinements. We look forward to hearing from you!

Throughout the Middle Ages, the feast of the Presentation of Christ was observed on February 2nd, where it gradually absorbed the rites of the Purification of the Virgin.[1] Incorporating blessed candles and certain songs, the feast came to be known as Candlemas. The only gospel writer to describe the Presentation of Christ in the Temple was Luke in the second chapter of his Gospel account (Luke 2:22–39). Luke writes that, in accordance with Jewish tradition, parents were required to bring an acceptable offering in exchange for the priest’s redemptive blessing on their child. Luke notes that “a pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons” would fulfill the sacrifice (Luke 2:24). In Presentation scenes, the gathered doves, usually held by Joseph, signal Christ’s restoration under Mosaic Law. Over time, lit candles at this same ritual came to mark the Virgin’s cleansing and reentry into the temple.[2] In a stained-glass window in Canterbury Cathedral, we find Joseph holding both implements at the far left, a visual sign of the combined purpose of their visit (Figure 1).

When the Holy Family approaches the altar, Luke records two mystical occurrences that concern key witnesses in the temple. First, Simeon, the named priest from Jerusalem, prophesies the divinity of the Christ Child.[3] Another prophetic utterance comes from the lips of an unlikely source, the temple’s aged widow, Anna the prophetess. Luke tells us that Anna fasted and prayed there without ceasing. Anna is the New Testament’s only prophetess, and her privileged glimpse of the important ritual uniquely connects her to the childhood of Christ.

The Presentation is Anna’s one shining moment in the Gospels. In the Index of Medieval Art there are over 960 examples of the subject Christ: Presentation, and at least 330 include Anna as a secondary figure in the scene. We discover varied depictions of Anna in these medieval images. She is depicted as a scroll-bearing prophetess; as proxy to the presentation ritual, handling the different ritual items; or she may be simply shown among the other women surrounding the Virgin Mary. Despite her prominent role at the Presentation of Christ, Anna’s portrayal in medieval images can be perplexing. It seems medieval artists, who knew about her visionary role at the Presentation, could choose to emphasize or de-emphasize Anna as a prophetess based on tradition, context, or perhaps even their own interpretations of her significance. Several Presentation scenes also include a woman near the altar, and Indexers have often identified her as a female attendant, questioning her identity as the prophetess in iconographic descriptions.[4] Thus was born the usual Index reading of this female figure: “probably Anna.”

Because of the inconsistency of representations of the Presentation, it is not always easy to identify Anna in medieval images. Moreover, Luke’s account offers few details about her, other than that she is:

Analysis of Presentation scenes does reveal a few key details consistently associated with Anna: the presence of a halo; her scroll, which expounds her part in the prophecy; her interaction with presentation/purification implements, including the doves and candles; and her advanced age, sometimes suggested by her modest wimple. One or more of these details could be enough for a positive ID of our prophetess. Another sign is her speaking gesture, as in the Presentation miniature in the Romanesque Mont-Saint-Michel Sacramentary, in which Anna’s hands are shown outstretched in a wide statement of praise (Figure 2). This miniature also exemplifies an iconographic conundrum that sometimes accompanies Anna: a second nimbed and veiled female figure stands just behind Joseph, and she is carrying two doves in draped hands. Is this a second Anna? Or is this simply a sanctified female attendant? This female assistant is doing what many later Annas do in bearing the sacrificial birds, so the context with which we identify Anna becomes increasingly important.

Anna is one of the first people, even the first woman, to reveal Christ’s destiny, but her exact words are omitted from Luke’s account. We know that she “spoke of him to all that looked for the redemption of Israel” (Luke 2:38). However, since Anna’s actual words are not recorded, her scrolls present a number of different inscriptions. An Index search reveals some of the most intriguing ones. In the fifth-century sanctuary apse mosaic at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, Anna’s scroll is inscribed BEATVS VENTER QVI TE PORTAVIT (Luke 11:27), meaning “Blessed is the womb that bore thee.” In a late twelfth-century mosaic in the Cathedral of Monreale, Anna holds a scroll inscribed POSIT(US) EST HIC I(N) RVINA(M) (Luke 2:34), repeating the words first said by Simeon, “This child is set for the fall.” In a fifteenth-century panel by the artist known as the “Byzantine Painter,” Anna holds a scroll inscribed (in Greek) “This child created Heaven and Earth” (Figure 3). And in one emotive declaration in a ca. 1240 Psalter from Hildesheim, Anna’s scroll is inscribed in Latin, EXULTATUIT COR MEUM (I Samuel, 02:01, also known as the Canticle of Anna), meaning “My heart hath rejoiced” (Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. Don. 309, fol. 37r).

Anna’s scroll has even been used to identify her by name, as in the presentation scene on the ca. 1365 Florentine Ashmolean Predella, from a private collection in Tuscany, with a scroll inscribed “ANNA PROFETESSA DEO GRATIAS AMEN” (“Prophetess Anna, Thanks be to God”). In this case, Anna’s index finger is elegantly lifted upward to indicate from whom her proselytizing originates. In other examples, Anna’s scroll can be completely blank, or filled with a pseudo-inscription. In the Armenian T’oros Roslin Gospels, the scroll expands into neat folds revealing simple red rulings (Figure 4).

The new advanced filter options offered by the Index database can reveal interesting trends within the Anna images recorded by the Index. I performed a keyword search for “Anna,” filtering by the subject Christ: Presentation, and restricted the search to fifteenth century examples (setting the date slider at 1400 to 1499). I limited these examples further with the Work of Art Type filter set to “Manuscript.” This way, I found over 60 records of interest describing fifteenth century illuminations that include this scene.

I narrowed these results further by adding a second subject filter with one of the Index’s grouped terms, Candle: held by Prophetess Anna. I found that, with each refinement, I was able to reconstruct Anna’s changing representation in medieval iconography. Curiously, in several of these late medieval examples, Anna is holding both a candle and a dove, and she is directly behind the Virgin Mary (not Simeon), displacing Joseph completely. These three-character scenes of the Presentation make up a good portion of later examples, and they underscore Anna’s union with the Holy Family’s first official appearance. In one such image, a fifteenth-century Book of Hours made in Paris, Anna is holding a candle in her right hand while playfully balancing a basket of birds on her head. A talented multitasker, Anna has, in a sense, usurped Joseph’s gift-bearing role (Figure 5).

No matter how she appears—as a wise widow bearing her scroll, or as a female witness bearing the implements of the impending ritual—the prophetess Anna is an exemplary New Testament woman. Through her time-honored vows of chastity, piety, and obedience to God, virtuous qualities brought out in her varied iconography, she presents a model of behavior for the young mother.

Further Reading

Shorr, Dorothy C. “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple.” The Art Bulletin 28, no. 1 (1946): 17–32.

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art, vol. 2, The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, trans. Janet Seligman (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1972): 90–94.

Elliott, J. K. “Anna’s Age (Luke 2:36–37).” Novum Testamentum, 30, Fasc. 2 (Apr., 1988), 100–102.

Hammond, Joseph. “Tintoretto and the ‘Presentation of Christ’: The Altar of the Purification in Santa Maria Dei Carmini, Venice.” Artibus Et Historiae 34, no. 68 (2013): 203–217.

“Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple.” In The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art & Architecture, edited by Murray, Peter, Linda Murray, and Tom Devonshire Jones: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Witherington III, Ben. “Mary, Simeon or Anna: Who First Recognized Jesus as Messiah.” Accessed 2 February 2018: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/mary-simeon-or-anna-who-first-recognized-jesus-as-messiah/

Notes

[1] From at least the fourth century this ritual was celebrated as a post-purification feast, known as Hypapante, which Justinian set 40 days after the feast of the Epiphany, or on February 14.

[2] For the best study of the development of this iconography, see Dorothy C. Shorr, “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple,” Art Bulletin 28 (1946): 20–46.

[3] Simeon holds the infant in his arms and instantly says to the Virgin Mary, “Behold this child is set for the fall, and for the resurrection of many in Israel…,” and representations of Simeon are associated with the text Nunc Dimittis, also known as the Canticle of Simeon (Luke 2:34–35).

[4] Shorr notes that, in most northern medieval examples after the thirteenth-century, Anna’s place was taken over by a young handmaiden (Shorr, 1946, p. 27).

The medieval New Year was not always celebrated on January 1. Although this was the first day of the Roman civil calendar, which eventually was adopted in much of the medieval world, people of the Middle Ages often marked the start of the year with celebrations on March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation; on the near-springtime date of March 1; or even on Christmas or Easter. Nonetheless, in medieval iconography, January continued to be associated with images of the ancient Roman deity Janus, who personified both the month and the transition and reflection that accompanied the change of the year.

Fig. 1. Coin with laureate head of bearded Janus, 209–208 BCE (or later). Crawford 100/1a (citing 6 specimens of all varieties in Paris); Sydenham 309a.

Janus was among the oldest gods venerated in ancient Rome, where he was associated with doorways, gates, and arches (one word for which was the Latin ianus) as well as temporal transitions. Ovid’s Fasti, an unfinished Latin poem on the Roman year, opens the kalends (first day) of January with an appeal to “Two-headed Janus, source of the silently gliding year, /The only god who is able to see behind him,” asking him to bring a favorable year. As early as the third century BCE, Janus was commemorated on coins as a bust with two bearded faces looking in opposite directions from a single neck, illustrating his ability to see both past and future (Fig. 1).

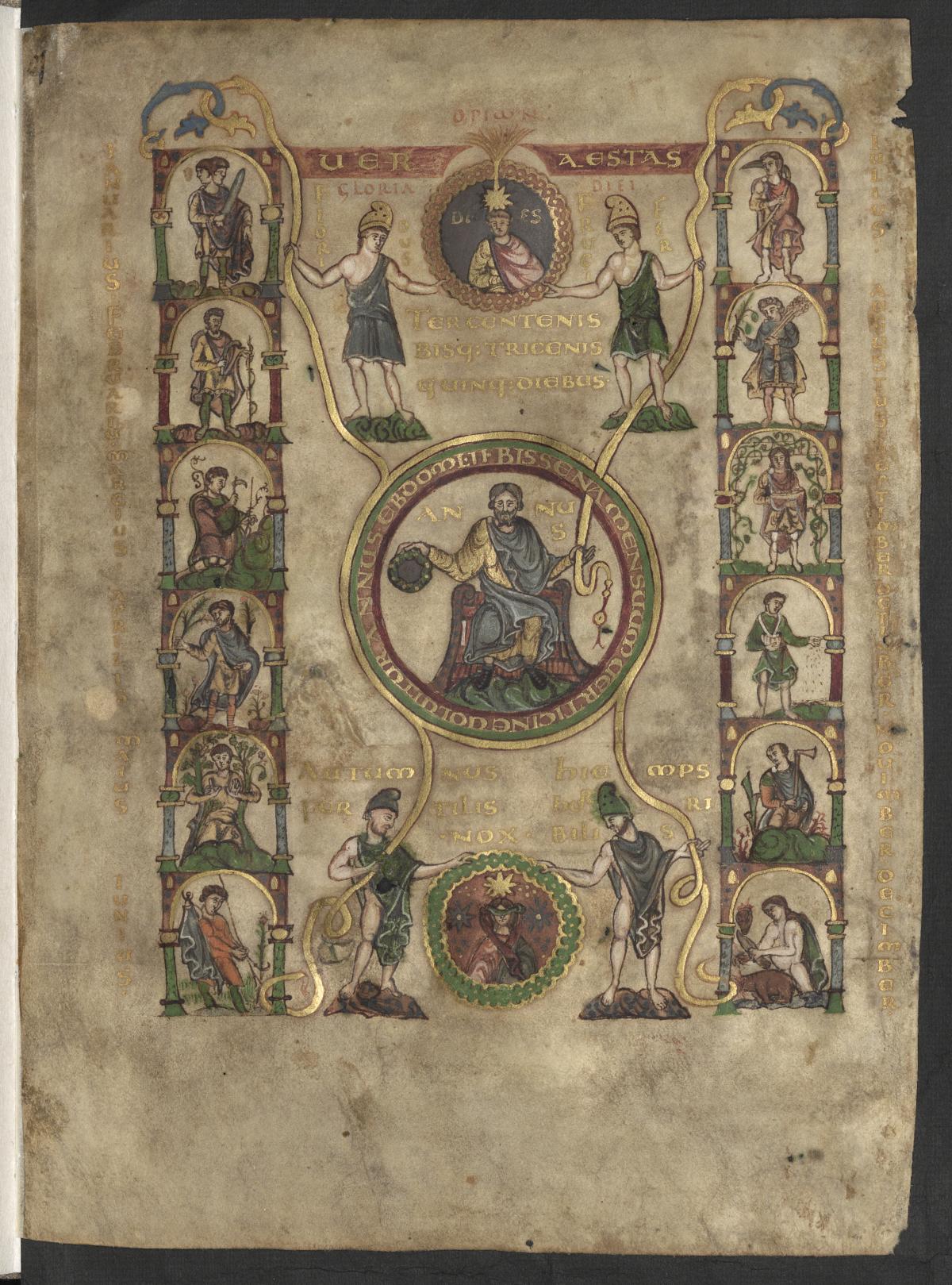

Janus’s status as overseer of temporal change persisted into the Middle Ages. In City of God (Book 7, ch. IX), Augustine wrote that “ad Ianum pertinent initia factorum” (the beginnings of accomplishments belong to Janus), while in his own Etymologies, Isidore of Seville associates the figure with the month of January and describes his double face as representing the beginning and the end of the year. Although Janus was occasionally represented in other visual contexts, the vast majority of medieval imagery relates to this timekeeping role.

Fig. 2. Calendar from a sacramentary made in Fulda (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, MS theol. Lat. fol. 192, fragm.), ca. 975.

In the Middle Ages, Janus most often appeared as the sign for January in calendrical cycles such as zodiacs and occupations of the months. An early example appears in a calendar page from a fragmentary late tenth-century sacramentary produced in Fulda (Fig. 2). Here, Janus appears at the upper left as a youthful foot soldier with sword drawn, his two faces turned vigilantly over each shoulder.

Fig. 3. Painted roundel depicting Janus, inscribed “Genuarius” (January), Panteón de los Reyes, San Isidoro, León, after 1109.

In the early twelfth-century calendrical cycle painted in the Panteón de los Reyes in San Isidoro of León, a roundel labeled “Genuarius” (January) contains a representation of Janus standing between two portals, the left shut and the right open to suggest the closing of the past year and the opening of the coming one (Fig. 3).

Yet another variant is found on an archivolt of the Ascension portal of the west facade of Chartres Cathedral, which combines depictions of the zodiac with the labors of the months (Fig. 4). Here, Janus displays faces of different ages, one youthful and beardless and the other with a mature beard, emphasizing the passage of time from the old year to the new.

Fig. 5. Janus feasting, Fécamp Psalter (The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS 76F 13, fol. 1v), late twelfth century.

The medieval calendar traditionally associated January with feasting, so it is not surprising that Janus often appears at a laden table, both his faces engaged in eating and drinking. In the late twelfth-century Fécamp Psalter, he sits alone, one face sipping wine from a chalice in his right hand as the other chews a morsel of meat from his left and two servants wait to replenish his meal (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6. Detail of Janus, from January calendar page, Book of Hours (New York, Morgan Library & Museum, MS M. 27, fol. 2v), ca. 1420–1430.

In the medieval west, feasting scenes of this kind became common in the calendars of private prayer books, especially in late medieval Books of Hours. In a lavishly decorated French example produced between 1420 and 1430, possibly in Rouen, Janus sits snugly in a roundel at the bottom of the January page, enjoying double dishes of meat as a servant waits at his elbow (Fig. 6). The connotations of comfort and plenty in such images surely appealed to their wealthy viewers in the dark and cold of winter.

Fig. 7. Triple-faced Janus, detail of stained glass window of the Labors of the Months, Chartres Cathedral, ca. 1220.

The novelty of Janus’s double face sometimes inspired fanciful artistic interpretations. Some artists increased the number of his faces to three or even four, drawing on ancient and medieval traditions that linked the god with past, present, and future or the cardinal directions. A thirteenth-century stained glass window of the Occupations of the Months in the cathedral of Chartres cathedral depicts the figure with three faces; he stands in an open portal beside an image of the Aquarian water-bearer (Fig. 7).

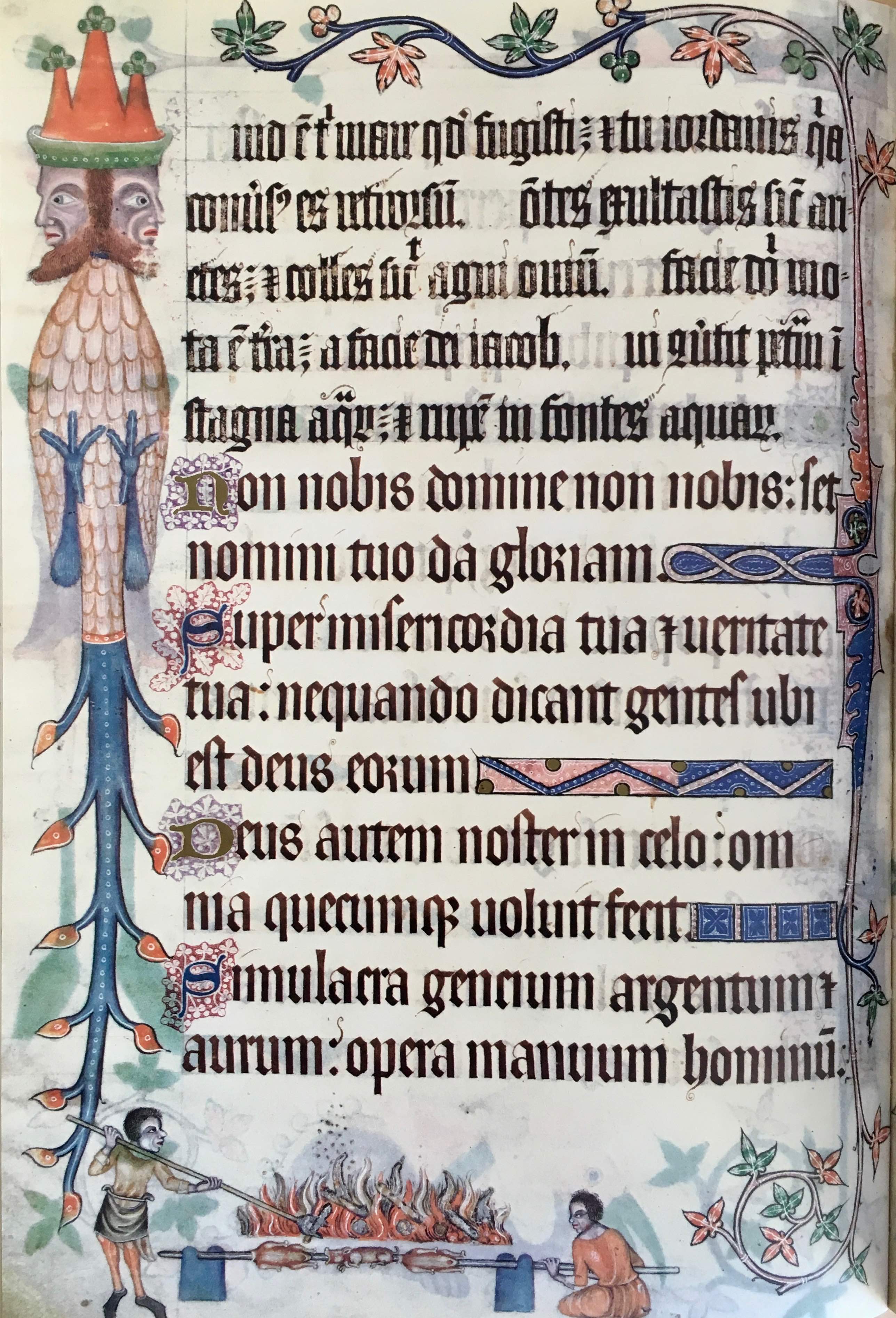

Fig. 8. Janus (?), Luttrell Psalter (London, British Library, MS Add. 42130, fol. 206v), ca. 1325–1335.

The illuminator of the fourteenth-century Luttrell Psalter, an artist of striking creativity, transformed Janus into a fanciful marginal hybrid, his double face, surmounted by a three-peaked red hat, affixed to a feathered bird’s body with a vinelike foliate tail (Fig. 8). Below, two dark-skinned servants prepare a meal in possible reference to the figure’s traditional feast.

A search for “Pagan Type: Janus” in the beta version of the new Index of Medieval Art database currently brings up 75 results, which can be filtered by date, location, medium, and other delimiters. We encourage you to explore these examples and more at our beta site, available to subscribing institutions at https://theindex.princeton.edu/

Further Reading

Ovid, Fasti, Book I: https://web.archive.org/web/20050419220209/http://www.tkline.freeserve.co.uk/OvidFastiBkOne.htm#_Toc69367257

Kühnel, Bianca. “The Perception of History in Thirteenth-Century Crusader Art,” France and the Holy Land: Frankish Culture at the End of the Crusades. Edited by Daniel H. Weiss and Lisa Mahoney. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004, 161-186, esp. 165-172.

Thraede, Klaus. “Ianus.” Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum. Stuttgart, Hiersemann1994), cols. 1259-1282.

Figure 1. Saint Nicholas of Myra Refusing Milk, ivory crozier, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1150-1185).

December 6 marks the feast day of Saint Nicholas of Myra, the source of our modern-day Santa Claus. We have taken this occasion to showcase the Index of Medieval Art as a tool for learning and researching about the iconography of medieval saints. The Index’s extensive collection of data had already offered users a chance to trace the saint’s history through art, and its archive of medieval images had granted researchers the opportunity to compare iconographies and expand their understanding of saints like Nicholas. Now, the multiple filters in the new database, currently in beta and undergoing daily refinements, allows users to retrieve, browse, and narrow search results in order to highlight the specificities of the saint.

The historical Saint Nicholas of Myra is an obscure figure. We know little more than that he was born in Asia Minor at the end of the third century and later in his life became a bishop of Myra. Nevertheless, he is one of the most popular saints of the Christian church, praised for his victories against demonic infanticide and his capacity of resuscitating dismembered bodies left in barrels to cure (yes, that’s right!). It should really come as no surprise, then, that the Index has 376 records of portraits and more than 600 representations of narratives and single figures of the saint.

But, if Nicholas’s life is virtually unknown, how did his cult and imagery develop to such a degree? The medievalists among our readers will already know that that the answer lies in another Saint Nicholas, that of Sion. The latter lived in the sixth century, and we have somewhat more information about him. Before the 10th century, these two saints, Nicholas of Myra and Nicholas of Sion, were merged by the literary tradition, and the voids left by the life of the former were filled by the latter. The fate of the two saints was sealed, and the archimandrite of Sion fell into darkness while the cult of the bishop of Myra flourished.

The cult of the bishop of Myra spread in both Eastern and Western Christendom. His life is represented in Byzantine monumental painting at least 31 times. The strengthening of his devotion saw a similar trend in the West. By the Renaissance, he had become the most popular saint in Europe. The Index allows for an interesting overview of the different contexts where Saint Nicholas’ cult developed. By browsing the Style/Culture filter, you can find 355 records identified as Gothic, 161 as Byzantine and 89 as Romanesque.

We know very little about Saint Nicholas’ childhood, but the Golden Legend assures us that he was incredibly pious from birth (literally):

While the infant (Saint Nicholas) was being bathed on the first day of his life, he stood straight up in the bath. And from then on, he took the breast only once on Wednesdays and Fridays.

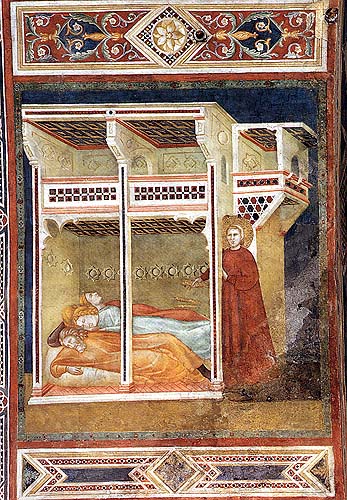

On a Crozier at the V&A, Saint Nicholas is represented sitting on his mother lap (Fig.1). She is offering her breast, but Saint Nicholas refuses, averting his head. With such a start, we should not be surprised that, as a young man, he decided to devote his inheritance to saving three sisters from prostitution (a real-life super hero!). The opportunity arose when a citizen of Myra lost all his money and could not support his three daughters. Nicholas heard of the situation and provided a dowry for each of the sisters. Among the 58 records with this subject identified in the Index database is a fresco in the chapel of Saint Nicholas in the lower church of San Francesco in Assisi (Fig.2). Here, he is represented as throwing three bars of gold through the window of a building where the three sisters and their father are sleeping.

Figure 2. Nicholas of Myra aiding the Dowerless Maidens, detail from the Chapel of Saint Nicholas, San Francesco, Lower Church, Assisi (1300-1349).

The nature of the dowry in this tale ranges from bags to balls to bars to coins of gold. In western iconography, the three balls become an attribute of the saint, and scholars have suggested a link between this and the pawnbroker’s symbol of three golden spheres suspended from a bar.

Besides helping maidens, Saint Nicholas is also known as the guardian of sailors, an exorcist and healer. By using the Creator filter in the Index, it is possible to examine this dimension of Saint Nicholas’s through the eyes of many artists. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, for instance, painted on panel several scenes from the life of the Saint, including that of the Resurrection of the Strangled Boy (Fig.3). The scene takes place in a two-story house, with the narrative beginning on the upper floor with the banquet scene. During the feast, the devil came to the door, dressed as a pilgrim and asking for alms. The boy is represented first at the top of the stairs, answering the door, and later at the bottom while being strangled by the devil. The story continues to unfold in the foreground where the boy is resurrected by the rays descending from Saint Nicholas.

Figure 3. Saint Nicholas of Myra Resurrecting a Strangled Boy by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Panel painting in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence (1300-1349).

Purely western is the peculiar story of Nicholas’s resurrection of three murdered boys. According to this tale, an innkeeper kidnapped and killed three youths. In the stained-glass window from Bourges Cathedral, they are shown reclining on a draped bed as the innkeeper raises his ax to kill them (Fig.4). At far right, Saint Nicholas extends his right hand in blessing toward the resuscitated boys, reflecting the legend’s account in which the innkeeper, having chopped up the boys, placed them in a barrel to cure. As an explanation for this, it is said that there was a famine during that year, and so the innkeeper was hoping to sell the cured meat as ham in order to make a living (sure, that makes total sense).

Figure 4. Saint Nicholas of Myra Resurrecting the three murdered boys, detail of a stained-glass window from the Chapel of Saint Nicholas, Bourges Cathedral (1205-1220)

The range of stories and miracles performed by Saint Nicholas developed with the saint’s reputation as a healer and the protector of children, unmarried girls, merchants, sailors, pawnbrokers and scholars. His popularity overall is reflected in the Index. Using the Work of Art Type filter, you’ll discover that because of this widespread cult, Saint Nicholas can be found in 169 manuscripts, and on 22 painted panels, 4 book covers, 2 miters, and 1 ring. Similarly, by browsing the Medium filter, we learn that there are 140 instances of depictions of Saint Nicholas in fresco, 37 in embroidery, 17 in mosaic, 15 in ivory, 8 in enamel, and 2 in niello.

It is only fitting that we should end with the death of Saint Nicholas, from whose remains a fragrant oil was said to flow, an oil that performed many miracles. But the story doesn’t really end here. Saint Nicholas’ body was stolen in the 11th century by Italian merchants and brought to Bari where it has been kept ever since. However, recent archaeological excavations in the church of Saint Nicholas in Demre (once known as Myra) have brought to light an intact tomb (soon to be opened) beneath the floor. Some believe this to be the original tomb of Saint Nicholas. If there’s a body in this tomb, does that mean that the relics in Bari are not of the saint after all?

We hope that by exploring images of Saint Nicholas in our database, you’ll also discover the many ways in which the new Index of Medieval Art can help you with your research. The database offers users the opportunity to expand and challenge previously acquired knowledge using new (still developing) filters that aid in narrowing the search thematically, iconographically, and stylistically. We have plans for other features as the beta continues to develop (though, not always as fast as we would like) offering new tools for discovery. And although this ongoing, expansive repository called the Index of Medieval Art does not hold all the answers, we hope that it will prompt you to ask more questions.

Maria Alessia Rossi, Kress Postdoctoral Researcher

As our regular readers know, the Index of Medieval Art recently launched a redesigned database. A challenging part of preparing for this event (codenamed Project Phoenix) was revisiting, reevaluating, and often revising how the Index has traditionally presented certain types of information. A century of accumulated data can reveal some unexpected things. Since the Index was founded in 1917, the history of the world has been…oh, let’s just call it “eventful.” Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the process of updating our outdated records as we upgrade the Index database has been a sobering reminder of all that has changed in the world, all that we have learned and achieved, and all that we have lost over the last one hundred years.

One set of data that made the need to revise our records very clear to us was the place names that we use. Obviously, names change, but we can point to a variety of reasons for the outdated information in the Index database. Some names in English are translations from the language of the place in question. In English usage, Wien remains Vienna, and Firenze remains Florence, but Lyon has superseded Lyons. Sometimes it’s a question of both language and script. What rules of translation and transliteration should we prefer? Depending on who is speaking or writing, a single place can be known by many names. For example, the Armenian place name Հռոմկլա can be transliterated as Hromkla, Hṛomkla, Hṛomklay, or Hrongla, but it can also be Rum Kalesi, Rūm ḳal‘esi, Rumkale, Qal‘ah Rumita, Qal‘at al-Rum, Qal‘at al-Muslimin, or Kela zêrîn. Can a single rule be applied consistently and make sense to users of the Index?

No matter the topic under discussion among the research staff at the Index, the answer to that last question turns out to be “no” frustratingly often. Language, like the rest of the world, is just too messy. One of our solutions, at least regarding how we handle locations, has been to embrace the messiness so that we simply have to account for complexity. So, when choosing an authority to cite for place names (authorities such as the Getty Thesaurus of Geographical Names and the Library of Congress, among others), we quickly decided that we need not cite the same authority in every case.

In addition to the problem of language, there are also outright changes of name that we have to recognize. The city of Byzantium has gone by a few different names in its history (Fig. 1). It’s called Istanbul now, but Istanbul was Constantinople. Now it’s Istanbul, not Constantinople. Believe it or not, that change became official many years after the Index was founded. It’s also worth mentioning that, although the name of that city should really be spelled “İstanbul” in Modern Turkish (with a dotted capital “İ”), the Index will continue to use the spelling familiar to English readers. Thus, even for something in situ, the database might list different names for an object’s or monument’s location of origin and its current location. Hagia Sophia is in Istanbul, but it was in Constantinople. (Have we given you an earworm yet?) Nevertheless, as we update the Index database, we will cross-reference place names so that, for example, a search for Istanbul (or İstanbul) will always also lead you to Constantinople.

But it’s not only names that change. Borders also sometimes shift. Once upon a time, when the Index was new, the city of Königsberg was in Prussia. After World War I, Königsberg was part of Germany (the Weimar Republic, that is, and then Nazi Germany), and by the end of World War II, much of the city had been destroyed, including museums and medieval monuments. That makes Germany the last known location for those buildings and the objects they contained (Fig. 2). Once the Prussian home of Immanuel Kant, Königsberg is now within the Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland. And, oh yes, it’s called Kaliningrad now. Our goal at the Index of Medieval Art is to continue to update our database to account for such changes.

By the way, for those of you as interested in topology as you are in topography, Kaliningrad was—when it was Königsberg—the subject of a famous logic puzzle. The city straddles the Pregel River, and there are two islands in the river, a feature reminiscent of Paris. The islands in Königsberg were connected to the rest of the city, but the bridges were configured in such a way as to give rise to this puzzle: “Can you walk through Königsberg crossing each of the seven bridges only once?” This puzzle has rules, of course: you have to cross each bridge only once, and you must cross each bridge completely (without turning around in the middle), but you may not cheat with a boat or hot air balloon. The puzzle was solved in the 18th century by Leonhard Euler, the great Swiss mathematician and general smarty-pants. When it comes to walking through Königsberg, crossing each of the seven bridges only once, Euler proved that…spoiler alert…it couldn’t be done!

Time does things to maps. Not only do place names change and frontiers shift, but cities rise and fall, roads are rerouted or renamed, and buildings are razed or rebuilt. Sometimes new bridges replace old ones, so that even that famous logic puzzle about the seven bridges of Königsberg has been affected by the last two centuries of human history. Only two of the bridges that Euler knew still exist, and the new configuration of bridges means that the Königsberg puzzle is no longer a puzzle at all in Kaliningrad!

On a related note, have you ever wondered, “When is a map not a map?”

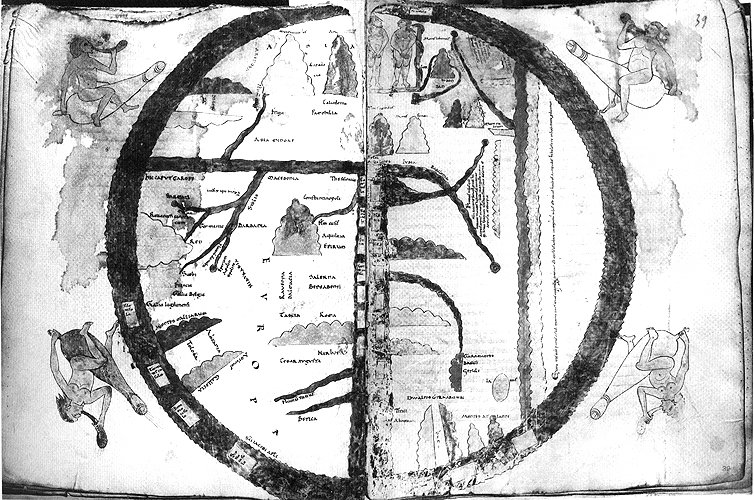

More precisely, the question that arose recently at the Index was this: “When is a map a map, and when is it a representation of a map?” Questions like this one can lead to surprisingly lively discussions at the Index of Medieval Art. This particular question came up while we were discussing how the Index ought to categorize certain subjects. It seems clear that some things are maps, like the Hereford Mappa Mundi. It also seems clear that some images include representations of maps, without actually being maps (Fig. 3).

However, some cases may be less clear, like a map in the Turin Beatus (Fig. 4). Is this an illumination that consists of a map, or is it a representation of a map? In other words, when is an object a map, and when is “map” the subject of an image?

What we at the Index sincerely hope is that you, everyone who uses the Index, will join us in addressing such questions. We invite subscribers to try out the Project Phoenix beta to see what we’ve been working on. We welcome your thoughts, so please tell us about your experience using the database, or share your observations about how we handle the content. Please bear in mind that this is the beta stage of development, so not everything is working perfectly yet. Some features have not been fully implemented, and some may be disabled from time to time while we work to improve them. It will also take us some time to edit the contents of the database so that everything is handled consistently within our revised format. In the meantime, the old, familiar database is still available to subscribers, and it will continue to be available until we are confident that the new version can supersede the old one.

We look forward to hearing from you. Your insights and feedback will continue to be vital to the success of this enterprise, just as they have been through the first 100 years of the Index of Medieval Art.

Henry Schilb