Modern study of medieval iconography inevitably entails grappling with exceptions and the rupture of expectations. No sooner might scholars settle on an expected visual formula—Cain killing Abel with his farmer’s hoe, Saint George riding his snowy steed—than we’re pulled up by an image that flouts those rules. In the fifteenth-century Alba Bible, Cain sinks his teeth directly into his brother’s neck, arguably in reference to Jewish exegesis, while in some Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons of St. George, a small boy carrying a cup rides with the saint, inspiring a semi-serious modern tradition concerning George’s love of coffee. Other iconographic traditions seem to emerge out of the blue, as did the distinctive type known as the Virgin of Humility, which flowered suddenly in Mediterranean cities in the 1340s. Such unruly iconographies both intrigue and disappoint us: they engage yet disobey our expectations, and we are left to wonder why.

The culprit in such cases is less often a rogue medieval work of art than the rigidity of modern scholarship. Despite ample evidence to the contrary, the assumption that medieval iconographic norms were formulaic, authoritative, and above all universally obeyed still shapes the way modern scholars analyze the imagery they study. Even after the poststructuralist turn, art historians have continued to wrestle with expectations deeply embedded in the discipline: that medieval artists preferred to copy or turn to text rather than to innovate; that unprecedented iconography must be based on a lost original; that patrons or learned advisors must have directed artists’ work; that traditions translated smoothly across media, formats, and contexts; that all viewers read and understood the images they saw in the same way. Underlying many of these assumptions has been a wider one: that the ideas of greatest value must be tracked to artists rooted in cosmopolitan centers, rather than to artists and works of art that circulated freely throughout their peripheries.

The conference “Unruly Iconographies? Examining the Unexpected in Medieval Art” aims to open a new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules. We call for papers, drawn from any area of the medieval world broadly defined, that ask both speakers and audience to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided which iconographic motifs are canonical and which are “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” At the broadest level, we seek to problematize the binaries on which these paradigms were founded: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, and center versus periphery. At a more specific one, we invite deeply researched case studies whose particularities can lead scholars to a more effective, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

“Unruly Iconographies?” will take place on November 9, 2024 at the Index of Medieval Art at Princeton University, following the Weitzmann Lecture by Dr. Brigitte Buettner, held on November 8 and hosted by Princeton’s Department of Art & Archaeology. It also will constitute the first of two internationally linked events, the second of which will be a site-based seminar at the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” in Naples in June 2025. Whereas the Index conference will consider broadly disciplinary questions about methodology, theory, and models, the Naples conference, hoped to be the first of several site-based conferences of this kind, takes southern Italy as a laboratory for exploring the relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages, focusing on the potentials and limits of the study of iconography in southern Italy. Details about this conference will be available in Summer 2024.

Submissions for the Princeton-based conference are invited by April 1, 2024. They should include a one-page abstract and c.v. and be sent to fionab@princeton.edu. Travel and hotel costs for the eight selected speakers will be covered by the Index. Speakers will be informed of their selection no later than May 1, 2024.

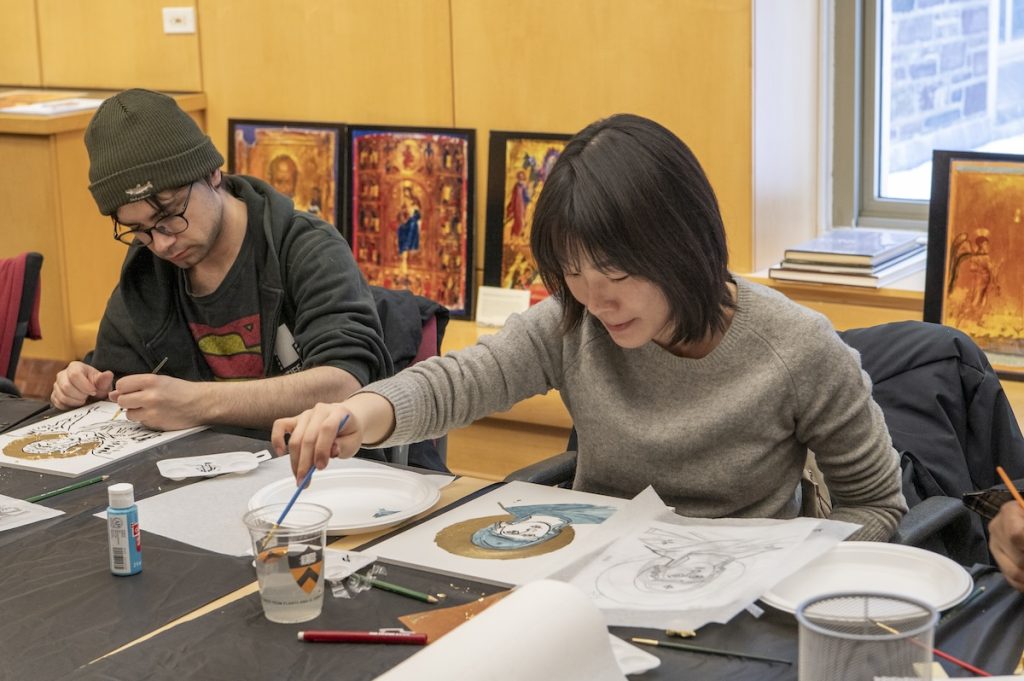

The Index of Medieval Art was delighted to offer its second Wintersession, “Exploring and Creating a Byzantine Icon: Then and Now,” on January 23rd, 2024. Its fifteen participants included Princeton staff, faculty, undergraduate and graduate students. In the first part of the workshop, they learned about the history and creation of Byzantine icons. In the second, they had the opportunity to create their own icons using modern artistic materials.

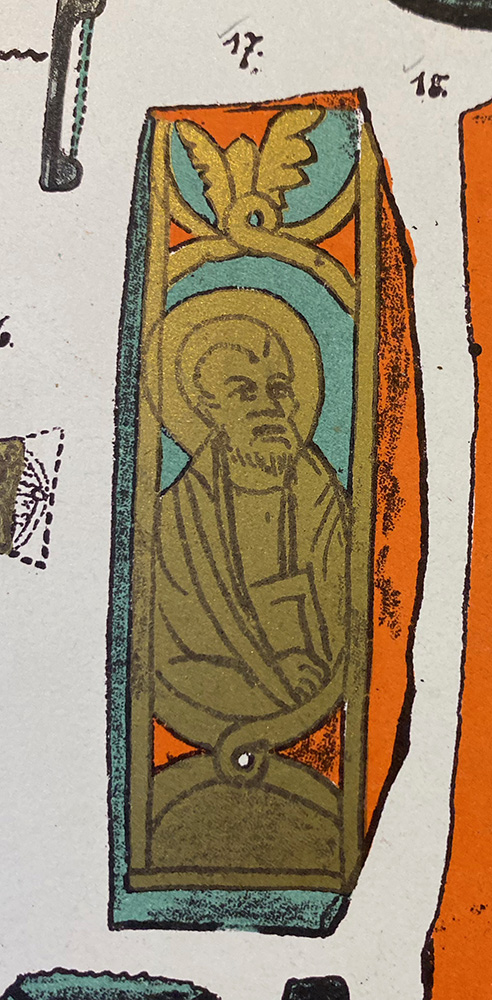

Index Art History Specialists Maria Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage led the workshop, opening with a presentation on the Index resources and delving into some questions about iconography using large reproductions of the icons from Mount Sinai, generously loaned by Visual Resources, as a basis. The group discussed the iconographic details in works of art, exploring the subject matter in icons that generate tags in the Index database. Jessica invited the students to observe the figures and scene in a twelfth-century Sinai icon of the Annunciation (Index system no. 57527), looking for major and minor details in the painting, as small as an octopus swimming underwater. Alessia introduced participants to the way Byzantine icons were displayed and their devotional practices by examining a folio from the Hamilton Greek Psalter (Index system no. 103381).

The first guest lecturer, local icon painter Maureen McCormick, showed the participants how to make the binder for egg tempera paint by mixing egg yolk and … No, not water … rather, white wine! Maureen showed the class all the tricks of the icon painter, including where to buy authentic pigments, how to grind them, and how to literally use one’s breath to “blow” gold leaf onto a red clay bole sample, which formed the nimbus of a saint. A short Instagram reel was made by Kirstin Ohrt, Communications Specialist in the Department of Art & Archaeology, to show Maureen’s breathtaking lesson in action, and you can check it out here: https://www.instagram.com/artandarchaeologyprinceton/reel/C2ud3gZLAJW/.

The afternoon session was led by Department of Art & Archaeology graduate student and icon painter, Megan Coates, who spoke about her own work with icons, as well as their importance for memory and communication. As part of an organized hands-on activity, participants created their own Byzantine icons using templates designed by Megan or choosing their own models from books or memory. Acrylic paint, brushes, drawing materials, gessoed panels, as well as gold and silver leaf materials were supplied by the Princeton Office of Campus Engagement. The outcomes were astonishing!

It was a pleasure to observe the participant’s ideas and skillful process unfold as they engaged in the long-treasured art of icon-making. One participant Sigrid Adriaenssens, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, wrote to us after Wintersession and said, “Thank you so much for organizing this workshop. It opened a whole new world to me that I didn’t know existed at Princeton. I really enjoyed learning about the Index, icons, and how they are made. The speakers Maureen and Megan were also very interesting and exciting to listen to!” Another participant, Zi (Zoe) Wang, visiting doctoral candidate and researcher at Princeton from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, said she felt transported by the instrumental music we played during the hands-on activity. Zoe said about the experience, it was like “immersing myself in meditation.” We couldn’t agree more!

Are you interested in learning more and researching icons at the Index? Here are some general tips for starting an Index search about Byzantine icons, especially if you do not know exactly which icon you are looking for!

However, these results might be too broad, so if you want to refine them you can keyword search the word “Byzantine” on the upper right search window of the database, and then filter by these other controlled terms we just mentioned, such as Work of Art Type “panel” or Medium “wood.” But if you want even narrower results, or if you know the iconography you are interested in, such as the iconography of an angel, or searching for angels by name, as in the case with the Annunciation image, you can filter by the Subject “Gabriel the Archangel.”

If you have any questions about starting research with the Index resources, fill out our inquiry form and we will be in touch: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/.

Finally, this Wintersession workshop could not have been possible without the generous support of the Princeton Office of Campus Engagement, the Department of Art & Archaeology, and the Index of Medieval Art. Thank you to all who helped plan and participated in this event!

As editorial staff at the Index continue cataloging our physical backfiles, which contain over 200,000 photographs of works of art in sixteen media categories, we are happy to announce that at last, all our print records of gold glass objects have been fully digitized in the Index database! In gold glass, an image in gold leaf is fused between layers of glass. Gold glass was a favored art form in Hellenistic Greece and during the Roman period, often decorating the bases of feasting vessels, such as bowls, cups, and plates, with hidden pictures that would slowly be revealed during the consumption of food and wine. The newly digitized “Gold Glass” backfiles document over 650 objects from about 60 locations. Most examples are identified as vessels, medallions, or plaques (Fig. 1).

The glittering portraits on these glass objects, now mostly fragmentary, are usually bust length and often show whole families. These are classified under the Index subject “Family Group,” while the subject “Married Pair” is used for images depicting a bride and groom, sometimes crowned by Christ. Gold glass objects are frequently associated with marriage celebrations, and several pieces retain the names of the men and women depicted with inscriptions of good wishes. Frequently, this inscription is the Latin drinking toast “PIE ZESES” (“Drink to live,”), either in full or abbreviated, although a fourth-century gold glass fragment from Rome, now in the British Museum, bears the more sentimental words “DVLCIS ANIMA VIVAS” (“Sweet soul, may you live [long]”) around the heads of the newlyweds (Fig. 2).

Several gold glass objects contain other paired figures, especially Peter and Paul the Apostles, as the patron saints of Rome, and Adam and Eve, commonly represented in the Fall of Man scene. Old Testament narratives and figures, such as Moses, Abraham, Daniel, and Jonah were popular, and Christian miracles were also frequently depicted on vessels. The Index database contains just over fifty miracle scenes executed in the gold glass medium, including the Raising of Lazarus, the Miracle of Loaves, and the Wedding at Cana, suggesting that healing themes held some favor among patrons. The objects may also have served a commemorative function.

Some surviving gold glass objects contain Jewish iconographic motifs, including the Temple implements, such as the menorah, shofar, etrog, and Torah Ark. These implements can be found in the Index database by browsing the Subject list, or by searching for “gold glass” as a term and filtering by the Style/Culture “Jewish.” Mythological figures and narratives from the classical world were also favored subjects to depict on gold glass vessels. The Herculean labors, sea-nymphs, and cupids can be identified on some fragments. Other well-represented motifs in the medium include the “Good Shepherd,” which has iconographic connections to the ancient Greek ram-bearing cult figure Kriophoros. There remains much to discover and assess about images in gold glass and their meanings, production, and patronage throughout the late antique, Roman, and Byzantine periods, making the Index an essential study tool. Now, with increased access, more researchers can learn how this rather fragile art form documents fashion, commerce, rituals, and historical names and epigraphs from ancient daily life (Fig. 3).

The Index gold glass backfiles received significant attention by Ryan Gerber, our 2019 summer intern from the Rutgers School of Communication, who is now a Marquand Art Library Collections Specialist. Gerber inventoried the collection and wrote about his impressions in a blog post called “A Face in Gold Glass.” After Henry D. Schilb, Index Art History Specialist in Byzantine Art, finished adding the collection with the help of Gerber’s inventory, he noted that many gold glass objects recorded in major nineteenth century catalogs did not survive into the modern era. Thus, the publications that earlier Index catalogers used in their research may have contained the last known record of an object’s existence. Schilb said, “it was surprising to learn that many of the gold glass objects entered into the Index files have been lost to time, and at least one of them was apparently reduced to dust in the collection where it was last recorded. Not surprisingly, we have also simply lost track of several examples that were originally cataloged by Indexers before the Second World War.” With too little information to go on, the Index cataloger can sometimes upload only a drawing from the catalog and record only a “Last Known Location” for objects presumed lost to history. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this in the database by giving “Unknown” as the current location with a “Last Known Location” to identify the place where an item was last known to exist. This can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are either simply lost or are now in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s true current location, that bit of data can sometimes elude us, so we always welcome intelligence from anyone who might have a good lead!

It is a great achievement when we can complete an entire category in the backfiles with newly researched information, including updated location names, fuller iconographic descriptions, and new or updated terms from Index vocabularies to expand the findability of work of art records. We ought to be clear, however, that we do not claim to have recorded every known example of any medium or type of object. That must remain an ongoing project. Nevertheless, the whole Index team is thrilled to make the gold glass corpus of the original Index card catalog fully available in the database. If you want to see for yourself, you can browse “gold glass” records by Medium more fully here: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/list/ListMediums.action. You can also reach out to us with any inquiry here: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/. Please let us know how the Index can improve the records we have, or find out how the Index can serve your own research needs.

Cheers!

Further Resources

Garrucci, Raffaele. Vetri ornati di figure in oro: Trovati nei cimiteri dei cristiani primitivi di roma. Rome: Tipografia Salviucci, 1858.

Deville, Achille. Histoire de l’art de la verrerie dans l’antiquité. Paris: Morel, 1871.

Vopel, Hermann. Die Altchristlichen Goldgläser: Ein Beitrag zur altchristlichen Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte. Freiburg im Breisgau: J. C. B. Mohr, 1899.

Morey, Charles Rufus. The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library: With Additional Catalogues of Other Gold-Glass Collections, ed. Guy Ferrari. Vatican City: Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1959.

Meek, Andrew. New Light on Old Glass: Recent Research on Byzantine Mosaics and Glass. London: British Museum Press, 2013.

Howells, Daniel Thomas. A Catalogue of the Late Antique Gold Glass in the British Museum. London, British Museum Press, 2015.

The Index is pleased to serve as site host for “The Medieval Multiple,” a conference organized by Sonja Drimmer (University of Massachusetts Amherst) and Ryan Eisenman (University of Pennsylvania), with support from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the International Center of Medieval Art, the University of Massachusetts Amherst College of Humanities and Fine Arts, Professor James Marrow and Dr. Emily Rose, and the Princeton University Department of Art & Archaeology. The conference will be held both in person and online.

Recent efforts to conceptualize the “pre-modern multiple” only occasionally reckon with the Middle Ages. Medieval multiples are frequently positioned against their modern counterparts—especially print—and subsequently presented as isolated, unrealized forms of mass (re)production. Yet the multiple was not an anomaly but rather the product of a common mode of artistic creation in the Middle Ages, found in a wide variety of materials and object types. Recognizing its ubiquity in visual and material culture, this conference brings together scholars to consider the multiple in the interconnected cultures of Afro-Eurasia between ca. 500 and 1500: its ontological status, the ways in which it could be produced, and how its makers and viewers recognized (or failed to recognize) replication.

For speakers and schedule and to register, please follow this link.

As many of the world’s traditions celebrate the returning light and the promise of new growth, the staff of the Index of Medieval Art wish all our researchers and friends a bright and peaceful winter break.

Our office and reading room will be closed Dec. 26 & 27, 2023, and Jan. 1 & 2, 2024.

For the second year, the Index of Medieval Art was pleased to offer the Graduate Student Travel Grant in an effort to support a non-Princeton student who wishes to attend the Index conference in person. The recipient this year was Anahit Galstyan, a PhD student in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who joined us in Princeton on November 11 and attended the “Whose East?” conference. We are glad to share her thoughts.

“It was an immensely enriching experience, and I found great enjoyment in the proceedings. The presentations were not only intellectually stimulating but also delivered with an engaging flair that made the entire event thoroughly enjoyable. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks for the generous grant that made my participation in this conference possible. Without such support, this experience would have remained beyond my reach. I think that by facilitating students’ attendance through the Graduate Student Travel Grant, the Index of Medieval Art contributes to the broader dissemination of knowledge and the fostering of academic dialogue.

“I found great merit in the engagement of the meticulously curated selection of participants in exploration and reevaluation of the entrenched dichotomies between East and West, Islam and Christianity. The discussions surrounding cultural interactions within the expansive region of the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond also further contributed to the recent scholarly discourse on questioning the traditional disciplinary predisposition of Byzantine studies to prioritize its metropolitan center, this way contributing to the reshaping of the dominant narratives in our field.

“Given my focus on the culturally and socially diverse medieval city of Ahlat and its funerary architecture, the exploration of intercultural exchanges at the event deeply resonated with my own work, making it not just intellectually engaging but also personally significant. I enjoyed all the presentations, with one of the standouts being Christian Raffensperger’s talk on the classification and categorization of Rus in medieval times. His insights provided a refreshing perspective that challenges established norms in the field. Anthi Andronikou’s presentation on interfaith dynamics between Eastern Christian and Islamicate art was also especially captivating among the various talks.

“I want to particularly highlight Gohar Grigoryan’s presentation, which provided a fascinating glimpse into first-hand accounts, shedding light on the intricate dynamics of Armenian elite self-fashioning in the thirteenth-century geopolitical context. It was particularly noteworthy in challenging the traditional view of a relatively uniform Armenian society during that era. Her paper was not just intellectually engaging but also skillfully presented, prompting me to reflect on my own research on identity creation. Grigoryan’s work emphasized the importance of examining the individuals I study not only in relation to external political dynamics but also in relation to each other, encouraging a more nuanced exploration of subtle expressions of personal identity. Additionally, Erik Thunø’s exploration of South Caucasian cross steles added another dimension to my understanding, urging me to consider similar cultural expressions beyond simple transmission.

“While attending the conference was truly delightful, I was also thrilled to have the opportunity to visit the numismatics collection. Handling and closely examining Byzantine, Cilician Armenian, and Seljuk coins was a highlight for me – an opportunity that I doubt I would have had as a grad student otherwise. Additionally, spending time in the Index was a wonderful experience. Dr. Maria Alessia Rossi and Dr. Henry D. Schilb provided invaluable assistance in navigating both physical and online catalogs to trace some types of funerary objects I study, such as censers and lamps, that are scattered across different collections worldwide. Finally, I am immensely grateful to Professor Pamela Patton for her generous hospitality and to Fiona Barrett for ensuring that I was well-fed throughout my stay.”

And we thank YOU, Anahit, for your thoughtful comments and for sharing your experience with the Index readers!

Anahit Galstyan is a PhD student in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on Christian-Islamic interactions in medieval Anatolia as manifested in the transculturation and the transmission of architectural knowledge.

By Henry Schilb, Art History Specialist

Is it lost? Was it destroyed? Did it ever really exist at all?

These are questions that we Indexers have to ponder all too often. We try to be both accurate and thorough in our descriptions of the objects in the database, but sometimes we get stumped. Although we Indexers understand that the database we’re building is an invaluable resource—that’s why we do what we do, after all, and we try to do it well—we also understand that there is room for improvement. The Index is neither complete nor perfect. There are gaps and errors in our data, and we know it.

But here’s the thing. In July 2023 the Index of Medieval Art was very pleased to announce that a paid subscription is no longer required for access to the Index database, a change made possible by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the support of the Index’s parent department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University. And now, to celebrate this change, we want to hear from you! Specifically, we want you to tell us what we’ve got wrong. Now that the Index is open to anyone with access to the internet, you can help us correct a mistake, if you find one, or fill in a lacuna in one of our records. It has always been important that we hear from all who use the Index, especially those who know things that we don’t, so what are you waiting for? You can use our Feedback form, or you can also contact one of the Research Staff directly.

Strange as it may seem, one of the most challenging pieces of information to verify is the present whereabouts of an object. As we catalog our oldest records, we sometimes run across works of art that we simply aren’t able to locate. An object’s location is the type of data that can change over time: things get lost; things get sold; things get stolen. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this by giving “Unknown” as the current location. You’ll find hundreds of examples in the Index. When possible we include a “Last Known Location,” the place where an item was last known to exist. A “Last Known Location” can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are lost or in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s current location, that bit of data often eludes us.

So, we’re asking for your help. Here are a few examples:

Can you help us find the piece of gold glass in figure 1? This is the only image we have, an illustration from a nineteenth-century publication. This piece is cataloged as Index system number jkg20200423001, and we have reason to hope that we’ll be able to find this one eventually. You see, a similar piece from the same collection—and illustrated in that same publication—is now in the MFA Boston (MFA accession number 1974.483 and Index system number hds20230131002).

An ivory diptych cataloged as Index system number hds20230620001 presents a similar problem (fig. 2). One wing is now in the Museum Mayer van den Bergh in Antwerp, but the location of the other wing is still unknown. Even the more specialized Gothic Ivories Project at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London lists the location of the left wing as unknown, so it’s not just us. Knowing the location of only one wing of a diptych can be frustrating, but we cling to our hope that we’ll eventually discover the present whereabouts of the other wing.

A more extreme example is cataloged as Index system number hds20230712001, an object formerly in the Rumyantsev Museum, Moscow. All the information we have comes from a nineteenth-century publication [Linas, Charles de, “L’Histoire du Travail a l’Exposition Universelle de 1867,” Revue de l’art chrétien 11 (1867): 344–45]. We have no other leads or clues. We don’t even have a photograph or a drawing to go on! Does it still exist? Is it a phantom? Can you help us find it?

Some of these items may still be in private collections; others may have been destroyed at some point after they were first entered into the Index of Medieval Art card catalog; but others may be sitting in storage in some museum in Oz, or Narnia, or even New Jersey, just waiting for you to point us in their direction. Could that be the case for the little chess piece entered in the database as Index system number hds20230330001 (fig. 3)? Formerly in a private collection in Paris, its current location is unknown to us. Is it in Peoria now? Or Paducah? Or even right here in Princeton? If you know the answers to any of these questions—or if you see other gaps that you might be able to help us fill—please tell us! With your help, piece by piece, we’ll make the Index of Medieval Art as accurate, thorough, and up to date as it possibly can be.

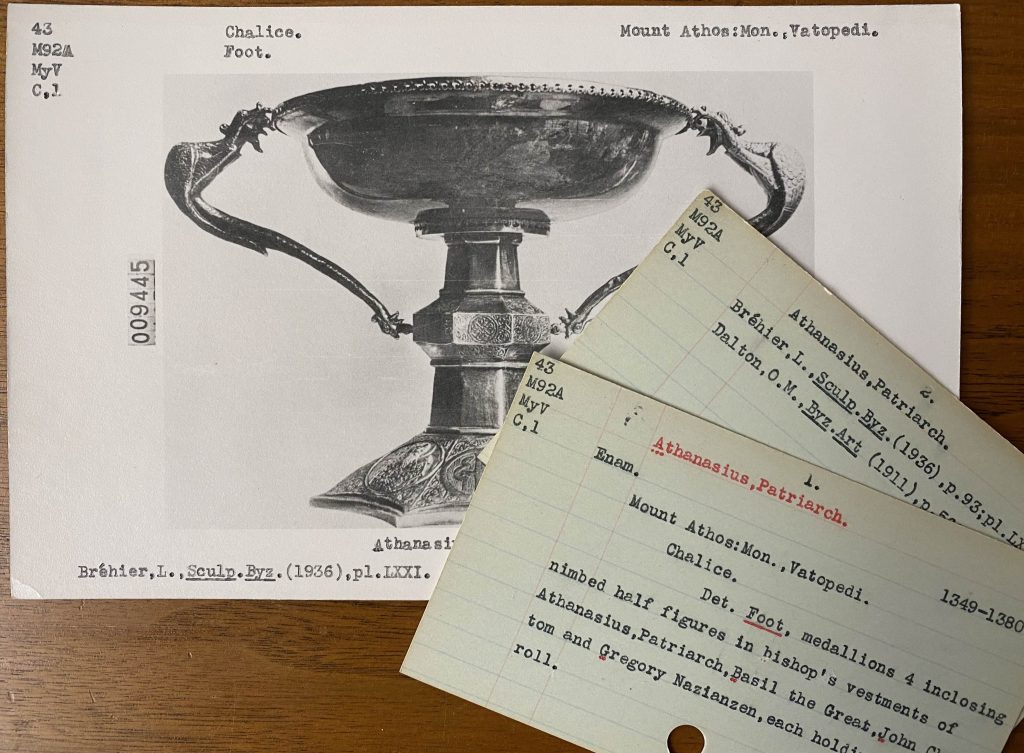

We are excited to announce a short-term graduate opportunity at the Index of Medieval Art! This is a two to three-month remote, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works of art on Mount Athos into the Index database. The position would require the student to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. They will be trained in Index norms in cataloging works of art, describing the iconography, transcribing inscriptions, and adding bibliographic citations.

The position is part of a new multi-year project, Connecting Histories: The Princeton and Mount Athos Legacy, that aims to create an international team of faculty, staff, and students that will explore and bring awareness to the rich, complex, and remarkable historical and cultural heritage of Mount Athos, and its connection to Princeton. This opportunity offers a stipend of $2,500 and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.

The deadline for applications is December 1, 2023. For more details about eligibility criteria and the application process, please visit the “Announcements” page on the Connecting Histories website.

Index staff have been busy at the Index working on a variety of projects and launching free public access to the database, which officially opened on July 1, 2023. It has been wonderful to see a warm reception from researchers, and recent user statistics show that the Index database is reaching hundreds of unique users per day.

We will continue offering Zoom tutorials and the next one is planned for the Spring 2024 semester. If you have been wondering how to get the best results out of your searches and see more about what the Index covers, please stay tuned for the next date, or write to us directly with your research inquiry!

We’re still accepting applications for the student travel grant award to attend this year’s Index conference in person (Deadline, 1 October 2023). Up to $500 will be reimbursed for a non-Princeton graduate student who wishes to attend the conferences but lacks the financial resources to do so. To see the full eligibility and apply, follow this link: https://ima.princeton.edu/graduate-student-travel-grant/.

The Index conference “Whose East? Defining, Challenging, and Exploring Eastern Christian Art” will take place on Saturday, 11 November 2023 in Julis Romo Rabinowitz A17 at Princeton University from 8:45am to 5:15pm (EDT).

Please note registration is not needed to watch the livestream, and the conference will be broadcast live at this link: https://mediacentrallive.princeton.edu/.