You know them by heart. You can hear them coming. Four notes, with six geese a-leading the way. Only four notes, but you can’t wait to belt them out. And then it happens:

“Five go-old rings!”

Those gold rings you love to sing about have been around since at least the eighteenth century, when the lyrics to “The Twelve Days of Christmas sung at King Pepin’s Ball” were printed in a little book called Mirth without Mischief (Fig. 1). [1]

No music was printed with the lyrics in Mirth without Mischief, but the words are roughly the same as you remember them, possibly representing the oldest printed evidence of the carol. The earliest known version of many different versions to come, it differs from the carol as we usually hear it today only in the order of the gifts from the ninth through the twelfth days. Partridge? Check. And two turtle doves, three French hens, and so on up to the usual seven swans a-swimming and eight maids a-milking, but then there follow nine drummers drumming instead of nine ladies dancing, ten pipers piping instead of ten lords a-leaping, eleven dancing ladies (probably preferable to the usual eleven pipers piping), and no fewer than twelve lords a-leaping instead of twelve drummers drumming. That’s just a lot of leaping lords, I must say! You’ll also notice that the birds on the fourth day were called “colly birds” back then, not “calling birds.” “Colly” just meant black like coal, so what we have is a flock of blackbirds. But all five gold rings were there already. Wait…is it “gold rings” or “golden rings”? I’ve heard it both ways, sometimes simultaneously. When exactly did “five gooooo-ooooold rings” become “five golll-dennn rings”? The version in Mirth without Mischief is clear about my true love’s having given me “gold” rings, not “golden” rings. It really doesn’t matter, I suppose, but the word “golden” does seem to devalue the gift. I mean, if the rings are only “golden” and not actual gold, then why do I want forty of them? Perhaps it’s just that even two notes per syllable is too much melisma for some carolers, so they need the extra syllable to sing.

Maybe I ought to get to the point. Typically, in this space, someone from the Index of Medieval Art will explore a topic relating to iconography, some theme or scene rendered in one or more media, perhaps a subject relevant to the season. This time, however, I want to look at a category of object. Yes, I’m going to show you five gold rings, each one cataloged in the Index of Medieval Art database. Of course, if you’ve ever done the math, you’ll be aware that my true love intends to send me not just five gold rings but a total of forty by the time Epiphany rolls around on the sixth of January. I always imagine the narrator of the carol wearing them all at once, or as many as possible, like Liberace or Ringo Starr. Presumably, when Ringo sings this carol, Barbara Bach is the “true love” in question. I wonder, has she ever given Ringo five gold rings, or would that be a bit “coals to Newcastle”? Er, Liverpool?

Really, we should be grateful that the familiar version of the carol includes inanimate objects on the fifth day. According to one reported version of the lyrics, instead of gold rings, you could have had “five hares running” to deal with (forty total, and…well, they’re hares, so, you know). [2] In that version, your true love also gives you four ducks quacking on the fourth day. But that version isn’t really a song. It’s a game of forfeits—in which each player takes a turn reciting the whole list and adding to it—a game that seems to be the origin of the structure of the lyrics of the carol.[3] And there’s another theory regarding how the fifth day wasn’t always about jewelry. It’s possible that our gold rings are a corruption of “goldspinks,” a Scottish word for goldfinches.[4] I suppose that would make more sense, given all the other birds my true love is sending me.

But I still prefer the familiar version of the carol that emerged in 1909, when Frederic Austin published his arrangement.[5] And the “five gold rings” part that’s so fun to belt out? It was Austin who composed those two famous bars and added them to his arrangement of the traditional melody, which was copyrighted by the publisher![6] It was also Austin who added the word “On” to the beginning of each verse. Interestingly, for the twelfth day, Austin doubled down on the melisma, so the final verse calls for the word “gold” to be sung with a flourish of four notes rather than the two usually sung today.[7]

OK, but what about those five gold rings I promised to show you? Whenever I hear “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” the rings I picture in my head are simple bands of gold, like the one Bilbo stole from Gollum in those Peter Jackson movies. But a gold ring can also be delicate openwork like this example at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Fig. 2, Index of Medieval Art system number 144086).[8]

On this early Byzantine ring, we find two birds (shall we imagine that they’re turtle doves?) flanking a vase among a scrolling grapevine. The crafting of this ring combined several methods. The birds, vase, and leaves appear to have been cut from a sheet of gold. The vine is filigree, delicate work created with gold wire.[9] The bunches of grapes were created by granulation, a technique in which tiny spheres of metal are fused together.[10]

As intricate as the openwork may be, this ring is still only a circle, a hoop without a bezel. The bezel is the “top” part of the ring that’s displayed on the back of the hand. A bezel can be flat, raised, incised, or filled with a gem.[11] There is even such a thing as a reversible bezel. The ring in figures 3a and 3b (Index of Medieval Art System number 60117), possibly from Syria and now at the Benaki Museum in Athens, has a swivel bezel with an image of Thekla of Iconium flanked by crosses and animals (probably lions) on the obverse (Fig. 3a).[12] On the reverse is an archangel holding a cross-staff and a globe (probably, though it’s hard to make out) (Fig. 3b).

If you were to inspect the edge of the bezel, you would find a Greek letter inscribed on each of the six sides not connected to the hoop. The characters ͵ϚΡΛ on three sides of the bezel are numerals, possibly giving the year 6130 of the Alexandrian Era (638/9 CE), or possibly having an apotropaic significance, while the other three letters—ΧΜΓ—are probably an abbreviation of Χριστὸν Μαρία γεννᾷ (Mary gives birth to Christ) or possibly something like Χριστός Μιχαήλ Γαβριήλ (Christ, Michael, Gabriel).[13]

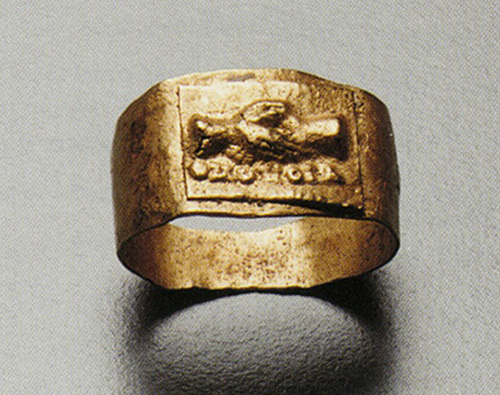

Although the space on any ring is limited, not every inscription on every ring is a cipher. For example, in the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University Bloomington, there is a Roman marriage-ring with a very straightforward message (Fig. 4, Index of Medieval Art system number 143736).[14] Below clasped hands in relief are the raised letters of the Greek word ΟΜΟΝΟΙΑ (ὁμόνοια, meaning concord, harmony, or like-mindedness).

The image and inscription were possibly created with a stamp or by working a small sheet of gold into a die.[15] The tiny relief was then applied to the gold band. The image is simple, and the significance of the word ὁμόνοια is quite clear.

The same word appears on the bezel of a somewhat later marriage-ring from the Eastern Mediterranean and now at the British Museum (Fig. 5a, Index of Medieval Art system number 62961).[16] The inscription and all the images on this ring, on both the hoop and the bezel, are rendered in niello, a metalwork technique in which a black alloy is used to highlight an engraved or incised image.[17] On the bezel we find the inscription OMONV/A (ὁμόνυα, a variant spelling of ὁμόνοια), but instead of clasped hands above the inscription, we see the Virgin Mary and Christ crowning the couple getting married, so the ring bears a representation of the person who wore it! Above this scene is a star. Yes, there’s a star…on a gold ring…so that makes it a gold ring star. Get it? You see, it’s funny because “gold ring star” sounds sort of like “Ringo Starr,” but inside out…. No? Never mind.

There are two more stars on this ring. Among the scenes from the life of Christ around the octagonal hoop, and on either side of the Baptism, there are stars in two scenes pertinent to this discussion of “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” the Nativity and the Adoration of the Magi (Fig. 5b).

Finally, the fifth gold ring that I want to show you is one of our Featured Works of Art for December 2021 (Fig. 6, Index of Medieval Art system number 200054). This Byzantine ring has been dated to ca. 900, but that date has been questioned.[18] There are niello crosses on the hoop, and on the bezel is a figure in enamel identified by name in niello as St. Nicholas. The image conforms to a familiar type, so we can recognize this figure as Nicholas of Myra. Yes, Virginia, he’s that St. Nicholas.[19]

And so, let St. Nicholas bring this story to a close. It remains only for me, on behalf of all the Index family, to wish you a joyous new year. May 2022 treat you like Ringo Starr…with peace and love.

Contributed by Henry Schilb, Art History Specialist.

Notes:

[1] Mirth without Mischief (London: Printed by J. Davenport, George’s Court, for C. Sheppard, No. 8, Aylesbury Street, Clerkenwell, [1780 or 1800?]), 5–16.

[2] Thomas Hughes, “The Ashen Fagot,” in Household Friends for Every Season, ed. James Thomas Fields (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1864), 34.

[3] Hugh Keyte, Andrew Parrott, and Clifford Bartlett, eds., The Shorter New Oxford Book of Carols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 229.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Frederic Austin, arr., The Twelve Days of Christmas (Traditional Song) (London: Novello, 1909).

[6] The copyright notice is at the bottom of page 2 of the sheet music, and the “five gold rings” motif composed by Austin first appears on page 4. Austin, The Twelve Days of Christmas, 2, 4. See also Keyte, Parrott, and Bartlett, The Shorter New Oxford Book of Carols, 229.

[7] Austin, The Twelve Days of Christmas, 11.

[8] Ioli Kalavrezou et al., Byzantine Women and Their World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 249, no. 141.

[9] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “filigree,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/filigree.

[10] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “granulation,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/granulation.

[11] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “ring,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/ring-jewelry#ref291658.

[12] Robin Cormack and Maria Vassilaki, eds., Byzantium, 330–1453 (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2008), 416, no. 149.

[13] For interpretations of the inscription, see especially Manolis Hadzidakis, “Anneau byzantin du Musée Benaki,” Byzantinisch-neugriechische Jahrbücher 17 (1939–1943): 175–81; Electra Georgoula, ed., Greek Jewellery from the Benaki Museum Collections (Athens: Benaki Museum, Adam Editions, 1999), 316–17, no. 117; and Cormack and Vassilaki, Byzantium, 330–1453, 416, no. 149.

[14] Kalavrezou, Byzantine Women and Their World, 222, no. 121.

[15] For a description of these techniques, see Wolf Rudolf, A Golden Legacy: Ancient Jewelry from the Burton Y. Berry Collection at the Indiana University Art Museum (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 6.

[16] Cormack and Vassilaki, Byzantium, 330–1453, 416, no. 150.

[17] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “niello,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/niello.

[18] Benaki Museum, “Collections & Archives > Byzantine Art,” accessed 14 December 2021, https://www.benaki.org/index.php?option=com_collectionitems&view=collectionitem&id=107623&Itemid=540&lang=en.

[19] Well, sort of. Readers curious about the journey of Saint Nicholas from Myra to Manhattan will want to track down a copy of Charles W. Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978). Although it’s a fairly old book now, and it was a bit flawed to begin with, it remains nonetheless an engrossing read, a good story well told.

This blog post is the first in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce Maria Alessia Rossi.

What is your background and specialization?

I joined the Index of Medieval Art initially as a Postdoctoral Researcher, and starting in September 2019, as an Art History Specialist. I earned my BA in History of Art from ‘La Sapienza’ University of Rome and my MA and PhD from The Courtauld Institute of Art. I work on medieval monumental art in the Byzantine and Slavic cultural spheres, cross-cultural contacts between the Eastern and Western Christian worlds, and the role of miracles in text and image.

What research projects are you working on currently?

For the Index, I research a wide range of medieval topics, but in my individual research and publications, I have been fascinated for a long time by the role of miracles in medieval society. During the Middle Ages, miracles played a crucial role in theology and propaganda, mirroring the needs, struggles, and desires of every social class. I have been surveying Christ’s miracles in late Byzantine churches in Constantinople, Mystras, Thessaloniki, Mount Athos, Ohrid, and Kastoria, and pairing the visual evidence with textual commissions, dealing with miracles of contemporary and older saints. The underlying question is what does the interconnectedness of visual and literary evidence dealing with miracles tell us about the contemporary social, religious, and political circumstances? One major outcome of this is a monograph tentatively titled Visualizing Christ’s Miracles: Art, Theology, and Court Culture in Late Byzantium.

Another topic I am passionate about is the rich, yet little-known art and architecture of Eastern Europe between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries. Modern borders, patterns of polarizations, and ideological barriers have prevented scholars from seeing a fuller and broader picture of these regions. Yet their geographical, religious, political, and cultural histories prove the interconnectedness of those territories at the crossroads of the Byzantine, Mediterranean, and Western European cultural spheres.

In this spirit, I co-founded the initiative North of Byzantium (NoB) with Alice I. Sullivan, a project sponsored by a 3-year grant from the Mary Jaharis Center for Byzantine Art and Culture, and the digital platform Mapping Eastern Europe. The aim is to place Eastern Europe on the map of art history by fostering a dialogue between scholars, promoting a sense of community, and facilitating research, teaching, and the study of its visual culture among students, teachers, scholars, and the wider public.

What do you like best about working at Princeton?

What I like best about working at Princeton University, and specifically at the Index of Medieval Art, is the people! There is a unique and constant inflow of scholars and students from all over the world who come to use the Index card catalogue and database. As an Indexer, you learn about their fascinating work, you help them find new materials and discover the Index, and you get excited with them when they stumble across unexpected finds. Scholars also gather to attend the Index conference, and this is yet another opportunity to discover recent and original research and engage in exciting conversations. Every year we also see our medieval community growing, with the arrival of new students and fellows, coming in with new topics, questions, and iconographic riddles to be resolved!

What travel experience played a role in your becoming an art historian?

Ever since I was little, my parents have taken me along on their trips. But did our vacations include beaches or time off? No, they were an endless list of archaeological sites, museums, and cities to explore. This usually meant that lunches had to be delayed to accommodate the busy schedule that ended up always (and I do mean always) including the main archaeological sites between noon and two p.m. under the burning hot sun! You would expect this to have turned me away from art and archaeology, yet here we are…. In time, these trips became research-focused, and the schedule became packed with Byzantine art and architecture. On one of these occasions, we made it to the remote location of a fortress built in the fourteenth century by the Serbian king Milutin. Of course, we were exhausted, and it was the middle of a very hot summer day, but I was absolutely overjoyed (as you can see in the photo). At that moment I knew there was no going back!

What do you like best about being back on campus in person?

The best part of being on campus is resuming the conversations and debates that make the Index thrive, and with it, the Middle Ages. Screens and planned meetings have not allowed for many of the spontaneous interactions that are at the heart of what the Index is about. When we are cataloguing, working on taxonomy, or implementing changes in our browse lists, we encounter issues and questions that benefit from broader conversations with the other specialists at the Index, such as how do we differentiate between James Major, James Minor, and James Brother of the Lord, or would it be better to use scroll or roll in our controlled vocabulary? We have weekly meetings where we discuss for hours (not ideal with zoom-fatigue during the pandemic!) the topics that we have encountered during the week. And when you visit us at the Index, you may even catch us in the middle of impromptu conversations in the corridor, sipping cups of coffee or tea, and chatting about the role of Tristan’s dog, Hodain, in the Legend of Tristan and Isolde, or about what work of art we should catalogue next and why.

Coffee or tea?

It’s tough…. Being Italian I would be tempted to say that nothing beats a good cappuccino! However, I do love my tea. And by “tea” I mean any kind of infusion, including Earl Grey, matcha, mint tea, hibiscus, jasmine, and the Tough Chai from Small World, our local coffee shop. I love trying new teas and talking about tea. So yeah, probably my answer would have to be tea!

The Index staff is pleased to announce the relaunch of the Index’s digital image collections, which have recently undergone a massive upgrade. The updated platform hosts ten collections of images generously donated to the Index and made freely accessible to the public through the Index website. These unique documentary resources include more than 50,000 images of medieval art and architecture and reflect the varied interests and travels of their twentieth-century photographers. They represent a range of subjects, techniques, and media, including English medieval embroidery, medieval and Byzantine manuscripts, European choir stall sculpture and stained glass, and Gothic and Romanesque architecture.

Although the images in these collections have not been cataloged with the same level of detail as those in the iconographic database, every effort has been made to assign them basic information regarding location, date, and in many cases, iconographic subjects. The latter can be found in browse lists that include a variety of iconographic topics, including saints and martyrs, animals, zodiac, occupations, and secular and religious scenes, all updated to follow the current subject standards of the main Index database. Browsing these subject lists reveals much about each collection. For instance, the subject list for the “Opus Anglicanum” database—an image collection of medieval English needlework on ecclesiastical and secular textiles—includes numerous saints especially venerated in England, with multiple scenes for Margaret of Antioch, Nicholas of Myra, and Thomas Becket.

Browsing the subject list of another collection, the Elaine C. Block database of misericords, reveals the wide variety of drôleries that decorated the wooden under-seat structures: fantastic creatures, battling animals, and figures playing in sports and games, engaged in occupations, or enacting proverbial lessons. John Plummer’s database of medieval manuscripts includes large numbers of biblical and apocalyptic images, including scenes with Christ, David, and the Virgin Mary, and other popular saints found in late medieval prayer books. The subjects in Plummer’s collection closely resemble those found in Jane Hayward’s collection, perhaps reflecting the shared interests of two scholars were curators at major collections in New York City during the second half of the twentieth century.

The Gabriel Millet collection comprises the study and teaching images of that scholar, an important archaeologist and historian of the early twentieth century who specialized in Byzantine art. Subjects represented here include multiple biblical figures and scenes, but also Byzantine generals and emperors and several text subjects, such as the Chronicle of Manasses and the biblical psalms by number.

The Gertrude and Robert Metcalf Collection of Stained Glass is a documentary treasure for the study of Gothic stained glass. The Metcalfs, who were both stained glass artists and experienced photographers, took more than 11,000 images of stained glass from European monuments, covering sites in Austria, England, France, Germany, and Switzerland. Their images of stained glass windows are a fascinating record of a fragile artistic medium, captured during fragile times. Their travels coincided with the dawn of World War II in Europe over the years 1937 and 1939, and they produced a body of documentary evidence that became critical to postwar restoration efforts. A look at the Metcalf subject list reveals many of the expected themes in medieval iconography, but also significant iconographic cycles for several French bishops, such as Austremonius and Bonitus of Clermont, Germanus of Auxerre, and Martialis of Limoges.

Geographically, the collections cover country and city locations in four continents—Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America—from obscure sites to famous ones, and they include many types of repositories, from in-situ locations to museums, libraries, and private collections. To better accommodate browsing by region, locations in all the collections have been formatted to begin with the country. Each collection is introduced with general information about its history, scope, and image use policies. It has been satisfying to edit and release these collections—now with more consistent information and a more secure digital platform—knowing that they are now more useful to scholars. Your feedback on the collections is welcome via this form.

Registration is now open for both online and in-person participation in the Index-hosted conference “Fragments, Art, and Meaning in the Middle Ages” on November 6, 2021. Navigate to our events page for current details about speakers and schedule.

In accordance with campus health and safety guidelines, on-site attendance in Rabinowitz A17 will be limited to those with building access approval from Princeton University, up to a maximum of 50 occupants. Face coverings will be required. All other participants are cordially invited to join the conference online.

Please use the links below for free registration. We look forward to seeing you there!

Use this link for in-person registration

Use this link for Zoom webinar registration

Studies in Iconography 42 (2021)

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to announce that volume 42 of Studies in Iconography, a peer-reviewed scholarly journal hosted by Princeton University and published by Medieval Institute Publications, has appeared both in print and online this year. While physical volumes will continue to be sent to print subscribers on an annual basis, from 2021 onward digital volumes will also be available through Scholarworks, the journal’s new online platform. Past volumes of the journal published from 1993 to five years prior to the current volume will continue to be available via JStor Complete. The current volume includes eight new book reviews and features the following articles:

“A Reconsideration of the Communion of the Apostles in Byzantine Art“

Vasileios Marinis

“Artists and Autonomy: Written Instructions and Preliminary Drawings for the Illuminator in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea (HM 3027)“

Martha Easton

‘A Lanterne of Lyght to the People’: English Narrative Alabaster Images of John the Baptist in Their Visual, Religious, and Social Contexts?

Kathryn A. Smith

“Metapainting in Fourteenth-Century Byzantium and Italy: Performing Devotion Through Time and Space“

Giulia Puma and Maria Alessia Rossi

“Frame for a Sultan“

Rossitza B. Schroeder

“The Implicating Gaze in Bronzino’s Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus and the Intellectual Culture of the Accademia Fiorentina“

Christine Zappella

Journal editors Diliana Angelova and Pamela Patton welcome the submission of original, innovative scholarship on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed, between the fourth century and the year 1600. Editorial guidelines and submission tools are all found on the Scholarworks site.

Continuing a series of blog posts introducing the new features of our online database.

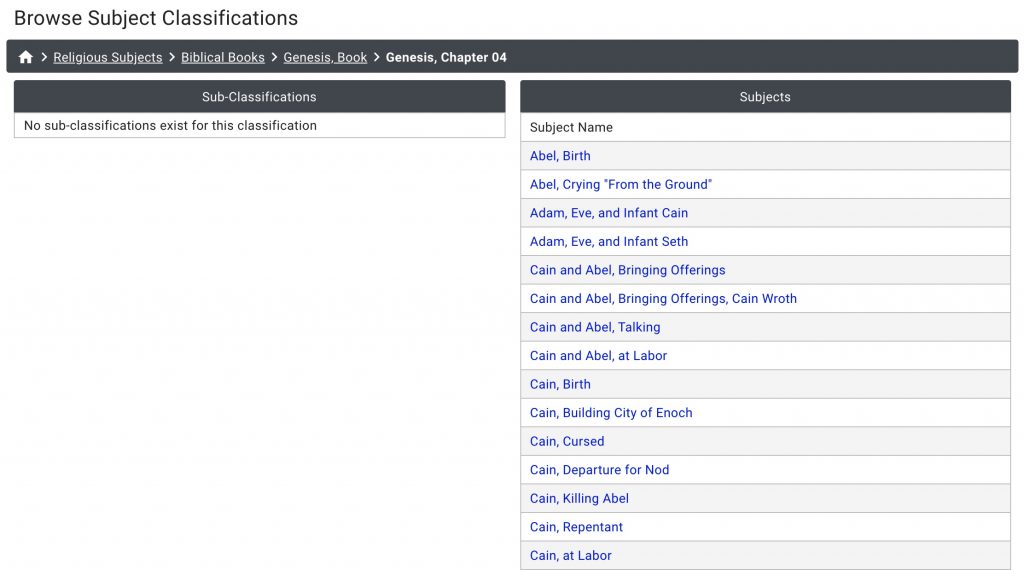

The Index of Medieval Art database catalogs more than 26,000 subjects. For a long time, you could explore this vast taxonomy only by browsing the subject headings in alphabetical order. To make the data more accessible, the Index has developed a Subject Classification browse tool, which allows researchers to discover Index holdings by browsing through various categories of our hierarchical classification of subjects.

In this network, subjects are grouped under five top-level headings:

By browsing the contents of these categories, researchers can learn more about Index subjects as grouped by theme. Researchers interested in the “History” category, for example, will encounter individual subjects, such as the names of historical figures and their associated scenes within a medieval society, grouped under classifications such as “Heraldry,” “Donors,” “Founders,” and “Nobility.” Other groups in this category include “Those Who Pray” (including representations of religious clergy, pilgrims, missionaries, hermits and heretics), “Those Who Fight” (with admirals, generals, officers, etc.), “Those Who Rule” (with emperors, empresses, doges, despots, prefects, etc.), and “Those Who Work” (including medieval occupations by type, such as philosophers, physicians, and scholars).

The category “Religious Subjects” contains diverse subject matter, mainly figures and scenes, but also objects and rituals, not only for the three Abrahamic faiths of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, but also for several other ancient religions, such as Greek, Roman, and Egyptian mythology. The unsurprisingly large iconographic groups for the Life of Christ and the Life of the Virgin Mary, which include the names of individual biblical figures and saints as well as biblical scenes, live in this part of the network and represent a wealth of catalogued examples in the database. Under “Religious Subjects,” biblical scenes are also grouped by their numbered books and chapters. These classifications allow researchers who are broadly interested in the iconography from a biblical source, such as the Genesis narrative, to access “Biblical Books” then “01. Genesis, Book,” and then go to a specific category. For example, the category “Genesis, Chapter 04” lists subjects of related figures and scenes appearing in Genesis 4, such as those for Adam, Eve, Cain, and Abel. Each biblical book with associated iconography in the database can be browsed for associated subject headings, including the subjects for the Psalms (following the Vulgate numbering 1–150). Researchers pursuing iconography related to texts other than the Bible will want to browse the “Literature and Legends” category, accessed from “Non-Biblical Texts” under “Society and Culture,” which contains subjects relating to the Trojan War, the Aeneid, the Legend of the Argonauts, and Arthurian Legend, among others.

The “Society and Culture” category contains a wide variety of subject terms for representations of medieval daily life. Here you will find types of work, garments, objects, utensils, musical instruments, and furniture that the Index has identified in medieval works of art, plus an array of occupational activities, such as travel, sports, eating and feasting, and hunting scenes. Exploring the category “Sports and Games” might yield unexpected names of pastimes enjoyed in the Middle Ages. Subject terms for games such as “Chess” or “Draughts” are familiar, but others, such as “Whirligig,” might invite a deeper look.

The “Nature” category is a treasure trove for anyone interested in medieval representations of animals, plants, geography, and astronomy. Here you will also find fascinating mythological creatures and hybrid figures alongside visualizations of the seasons, climate, and natural disasters. The “Symbol, Concept, and Ornament” category contains subjects for the more abstract topics in the Index collection. It currently organizes representations of allegories by name and personifications by type, including human characters for the arts, nature, places, time, virtues and vices. This category also includes maps and diagrams, monograms of individual figures, and various kinds of figured, floreate, and foliate ornament.

More a network than a strict hierarchy, the Subject Classification tool is designed to be flexible in its groupings, because the Index of Medieval Art recognizes that medieval iconography does not always fit into predetermined categories or may fit into many categories. For example, Charlemagne, the Carolingian King of the Franks and later Emperor of the Romans was also revered as a saint in some locations, so he appears in multiple parts of the network, including:

When clicking on the lowest-level subject heading, in this case “Charlemagne,” a new page will appear displaying this subject heading’s authority record. The authority record provides an array of useful information, including a Note field at the top offering a definition of the subject, or biographical details, followed by expandable fields containing select bibliographic citations, External References (cross-references to other authorities) and See Froms (alternative names and spellings of the subject). At the bottom of each subject authority is the Associated Works of Art field, an expandable field containing links to all the medieval works of art that feature this iconography.

The authority record’s Subject Classifications field presents the lowest network category, or categories, to which the subject belongs. In the example of “Charlemagne,” it is the name of the individual figure. In other instances, the Subject Classifications for a particular subject might appear on the authority as a broader grouping term. For example, the subject authority for “Drinking Horn” will use the subject classification “Utensils and Objects D–H,” and the subject for “Robin” will use the classification “Birds H–Z.” As noted in the example for biblical books, the subject classifications can also contain names of textual sources, including legends and other narratives.

The evolution of the Subject Classification tool is ongoing, allowing for continuous discovery by both those who use it and those who are building it. As branches of the network spread, new and surprising associations emerge, revealing the richness of the Index’s subject taxonomy. We hope you will enjoy browsing the iconographic headings with this new database tool, which is openly accessible to anyone who visits the browse page of the Index of Medieval Art database.

The Index of Medieval Art Subject Classifications comprises a browsable network that organizes and associates subject terms from our vast taxonomy of medieval iconography. These classifications are descriptive and not prescriptive of medieval works of art cataloged into the Index collection. What follows is an outline of the top three levels of classifications to give Index researchers the broadest overview of subject content.

Heraldry

Heraldic Symbols

Heraldry of Miscellaneous Figures and Families

Identified Heraldry A–Z

Legendary Heraldry A–Z

Historical Figures

Donors A–Z

Founders A–Z

Nobility

Those Who Fight

Those Who Pray

Those Who Rule

Those Who Work

Animals

Birds A–Z

Hunting and Other Scenes

Insects and Invertebrates

Mammals A–Z

Marine Creatures

Reptiles and Amphibians

Astronomy and Astrology

Constellations

Planets and Other Celestial Objects

Sun and Moon

Zodiac

Geography and Geology

Landscape

Minerals and Gems

Mountains

Natural Elements

Rivers

Sea and Ocean

Weather and Natural Disasters

Mythological Creatures and Hybrids

Animal Hybrids

Hybrid Figures

Mythological and Religious Creatures

Plants

Plants and Flowers A–Z

Trees and Their Fruits A–Z

Time

Months

Seasons

Times of the Day

Biblical Books

Genesis, Book–Maccabees, Book

Matthew, Book–Apocalypse, Book

Christianity

Angels and Devils

Christian Legends

Christian Objects and Rituals

Christian Religious Orders and Offices

Death and Afterlife

Divine Manifestations

Images and Attributes of Christ

Life of Christ

Life of the Virgin Mary

New Testament Apocrypha

New Testament Figures

Old Testament Apocrypha

Old Testament Figures

Saints

Types of the Virgin Mary

Greek and Roman Mythology

Mythological Figures A–Z

Mythological Narratives

Islam

Muslim Objects and Rituals

The Life of Muhammad

Judaism

Jewish Biblical Figures and Narratives

Jewish Objects and Rituals

Other Ancient Religions

Egyptian Deities

Gnosticism

Mithraism

Zoroastrianism

Architecture

Cities A–Z

Identified Buildings A–Z

Models of Buildings and Cities

Unidentified Buildings and Structures A–Z

Drollery

Drolleries and Grotesques

Figure Types

Ethnic, National, Religious, and Social Types

Figure Types A–Z

Human Hybrids

Hybrid Figures

Imaginary Figures

Labors of the Month

Months

Furniture

Bed, Bench, Lectern, Throne, etc.

Garments and Accessories

Hats, Headgear, Jewelry, etc.

Human Activities

Eating and Feasting

Hunting and Other Scenes

Medicine and Medical Practices

Occupational A–Z

Social Activities

Sports and Games

Travel and Commerce

Non-Biblical Texts

Literature and Legends

Objects and Rituals

Christian Objects and Rituals

Jewish Objects and Rituals

Muslim Objects and Rituals

Utensils and Objects

Musical Instruments A–Z

Utensils and Objects A–Z

Warfare

Arms and Armor

Military Figures

Military Scenes

Allegories and Personifications

Allegories

Personifications of Arts

Personification of Christological, Symbolic, and Literary Concepts A–Z

Personifications of Nature

Personifications of Places

Personifications of Time

Personifications of Vices

Personifications of Virtues

Maps and Diagrams

Alchemical, Alphabetical, Geometric, Astronomical Diagrams, etc. and Maps

Monogram

Monograms of Individual Figures A–Z and Symbols

Ornament

Animal, Figured, Floreate, and Foliate Ornament

Attending the 56th International Congress on Medieval Studies this year? Please join us for the two IMA-sponsored sessions on Wednesday, May 12th

190 Wednesday, May 12, 11:00 a.m. EDT: Location, Location, Location: In-Situ Iconography within the Medieval Built Environment I: Topography and Threshold

Location, Performance, History: The West Façade of Wells Cathedral Reconsidered

Matthew M. Reeve, Queen’s University

Of Columns and Column Saints: Architectural Appropriation at Qal’at Sim’an

Laura H. Hollengreen, University of Arizona

“Bearing Witness Then as Now”: Iconography and Epigraphy in the Latin Church of the Holy Sepulcher

Megan Boomer, Columbia University

The Lives of Cats, Eels, and Monks on an Irish High Cross

Dorothy Verkerk, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill

__________________________________

200 Wednesday, May 12, 1:00 p.m. EDT: Location, Location, Location: In-Situ Iconography within the Medieval Built Environment II: The Interior Space

“Feet of Clay”: The Significance of Media and Iconography in Thirteenth-Century English Architectural Interiors

Amanda R. Luyster, College of the Holy Cross

Transfiguring Frescoes: Framing Panel Paintings in Italian Medieval Mural Decoration

Alexis Wang, Columbia University

Folding and Archiving Monumental Images: Bertha’s Tablecloth for the Cathedral in Lyon (Ninth Century)

Vincent Debiais, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris

As of April 1, 2021, the Index-hosted journal Studies in Iconography has shifted to an online submission process, beginning with submissions for volume 43 (2022). Prospective authors may submit their manuscripts on our new Scholarworks site and will find further information both there and in the editorial policies and guidelines section of the IMA website. In addition, beginning with vol. 42 the journal’s annual volumes will be published both in print and online through Scholarworks, a shift that is hoped will increase their reach and accessibility.

Studies in Iconography is an annual journal hosted by the Index of Medieval Art and published in partnership with Medieval Institute Publications. Co-edited by Pamela A. Patton and Diliana Angelova, it presents innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed, between the fourth century to the year 1600. Past and current articles have addressed subjects as diverse as Byzantine fresco programs, Carolingian architectural diagrams, Gothic rent books, Jewish ritual images, Islamicate stucco ornament, and early modern portraiture. We especially encourage article submissions that offer interdisciplinary, theoretical, or critical perspectives, and works of both established and emerging scholars are welcome. Reviews of selected books on iconography and art history are included in every volume.

Inquiries about matters outside the online submission process may be directed to Fiona Barrett, fionab@princeton.edu.

For information about pricing, subscriptions, or back issues, please consult https://wmich.edu/medievalpublications/journals/iconography.

The Index of Medieval Art has completed a systemwide update aimed at making the database both more user-friendly and fully compliant with current accessibility standards. Launched April 1, the update includes the following improvements:

We encourage researchers to explore the updated site, making use of the new Help pages linked on the Welcome page. As always, we welcome your research inquiries and feedback.

NB: This satirical post was shared in honor of April Fool’s Day, 1 April, 2021

We might consider baseball as American as apple pie. Popular legend ascribes its invention to Abner Doubleday in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York, while historians of the sport point out that a similar game was played in North America as early as the late eighteenth century. Some, however, have hypothesized that the game had earlier roots in two early modern English games, rounders and cricket.

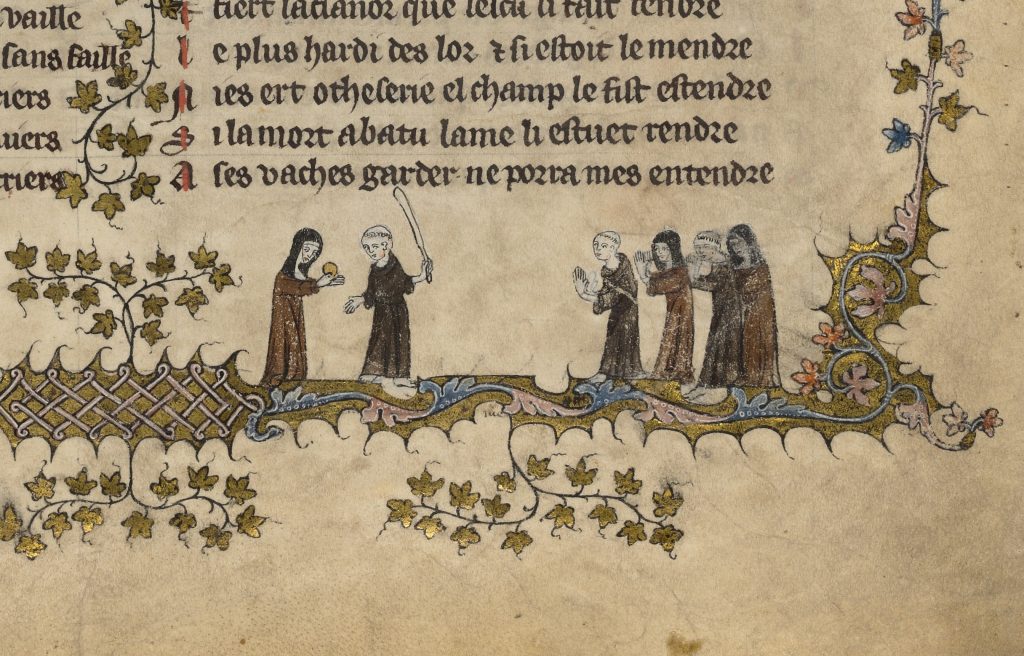

Yet there is evidence to suggest that baseball has far deeper historical roots, reaching back to the Middle Ages. The marginal decoration of a fourteenth-century French manuscript now in Oxford’s Bodleian Library (MS. 264) includes what may be the earliest conclusive illustrations of the game, played here by a group of nuns and monks. The nun at left has caught the ball just after the monk at bat has swung and missed. The monk turns to argue the count as two monks and two nuns in the infield raise their hands, ready to field, in a classic example of what Otto Pächt has called “simultaneous narrative.” The absence of outfielders in the scene was surely the result of artistic economy, given the limited space afforded by the gilded floral and foliate border, a decorative form that perhaps inspired the much later planting of ivy on the outfield wall at Wrigley Field, where players still contend with limited space.

The representation of the game’s players as cloistered religious figures offers a note of accuracy, as French nuns are in fact the earliest recorded players of the game that they called le base-bal. As early as the twelfth century, the nuns of the Abbey of Fontevraud in particular had established a reputation for their high on-base percentage and daring in run-downs; a certain Wilgefortis is lauded in conventual records for her lusty swing and reliability in the clutch. Barnstorming throughout the Loire valley, the Fontevraud nuns found the women of other convents eager to meet them between the lines, although the same could not be said of the monks and canons they challenged, most of whom refused to play, claiming the women “couldn’t throw.” The mixed-gender matchup depicted in the fourteenth-century Bodleian manuscript reflects a later era, when the dominance of the Fontevraud lineup had faded into distant memory and monks became more willing to test their skills against their slugging sorores.

Conventual baseball faded in Europe in the sixteenth century as reformers like Martin Luther turned popular opinion against the “devil’s game,” describing it as a gateway to luxury and vice and also complaining that the action was “too slow.” Today, it is only pictorial traces like that in Bodleian 264 that preserve the vibrant medieval traditions that gave us “America’s pastime.”