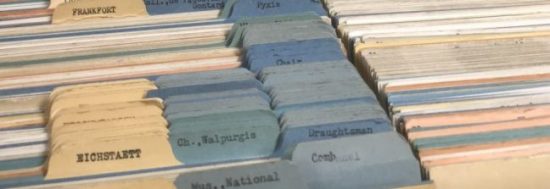

This summer The Index of Medieval Art welcomed two students from the Master of Information program at Rutgers University to inventory the Index’s photographic archive. Comprising nearly two hundred thousand cards in sixteen different medium categories, this historic image collection provides researchers a rich resource of sometimes rare visual references for the study of art produced throughout the Middle Ages. The inventories undertaken by Ryan Gerber and Michele Mesi have illuminated the extent of the archive and helped to assess the image and cataloguing needs for ongoing research and cataloguing at the Index. In this special two-part blog post, we are pleased to present their observations and accounts of their experiences.

It is a testament to the Index’s stimulating power that, despite my lack of an art-historical background, I found myself entranced by the system of cataloguing medieval iconography that the Index pioneered and is still practicing to this day. Its vision of greater accessibility through complete digitization represents another milestone in its long history, and one which will be a gift to scholars of all persuasions and experience levels.

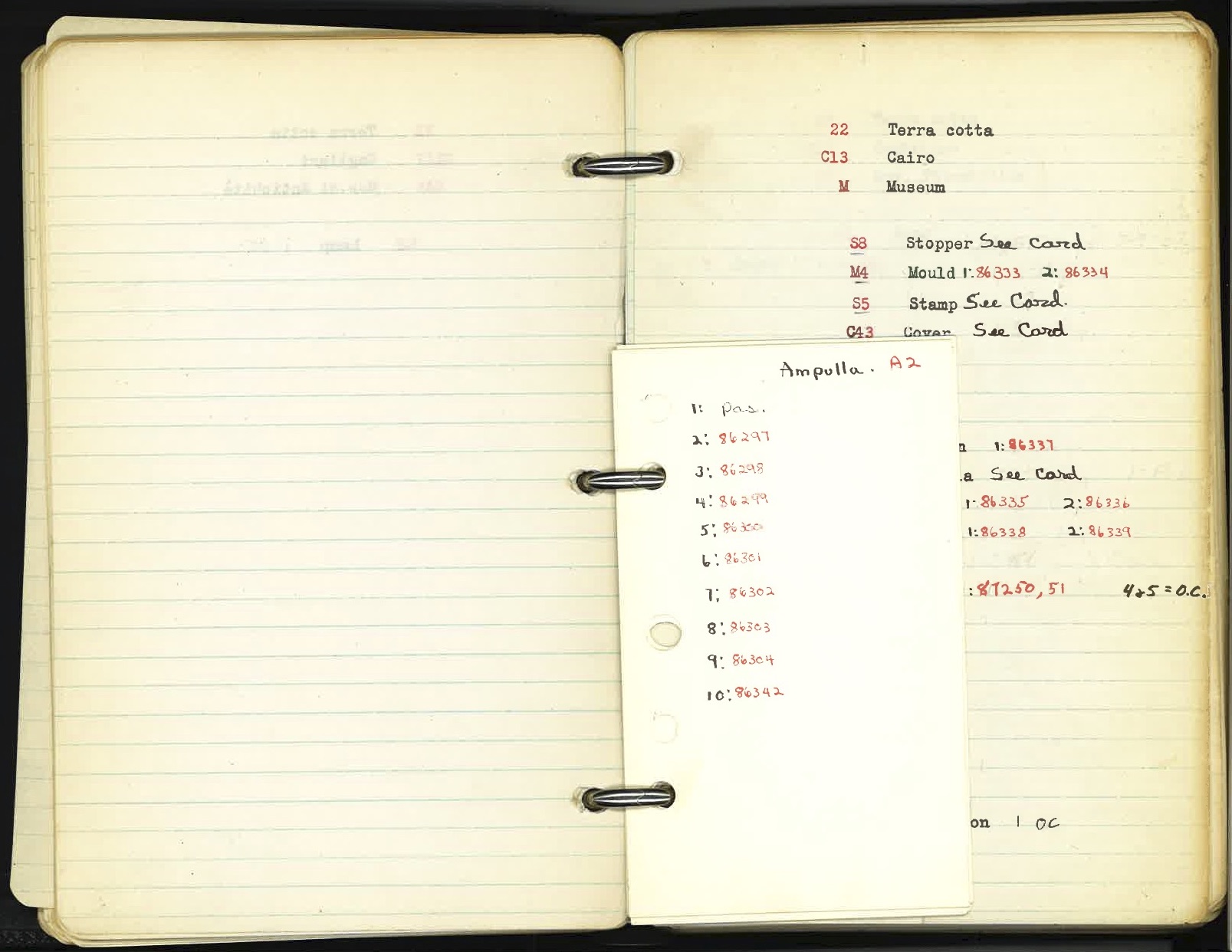

A system largely developed by Index director Helen Woodruff in the 1930s, the photographic archive is organized in the first place by medium, then by location, object type, and the numeric order within that group. Unique codes on the left-hand corner of every index card in the catalogue represent each of these levels of organization. The fruits of this labor are hard to miss after spending any time with the Index and its elegantly interwoven subject index and photographic archive, where one can move seamlessly from subject description to pictorial representations and vice versa.

This work has also left behind a trove of archival resources such as hundreds of rolls of film and the so-called “Black Books” that were used to track the negative numbers. Each of the medium categories I inventoried not only laid the groundwork for further analysis of the collection as a whole, but highlighted the Index’s remarkable century-old ability to generate new curiosities and paths of inquiry.

Terracotta, Temporary Cards, Lamps, and Lions

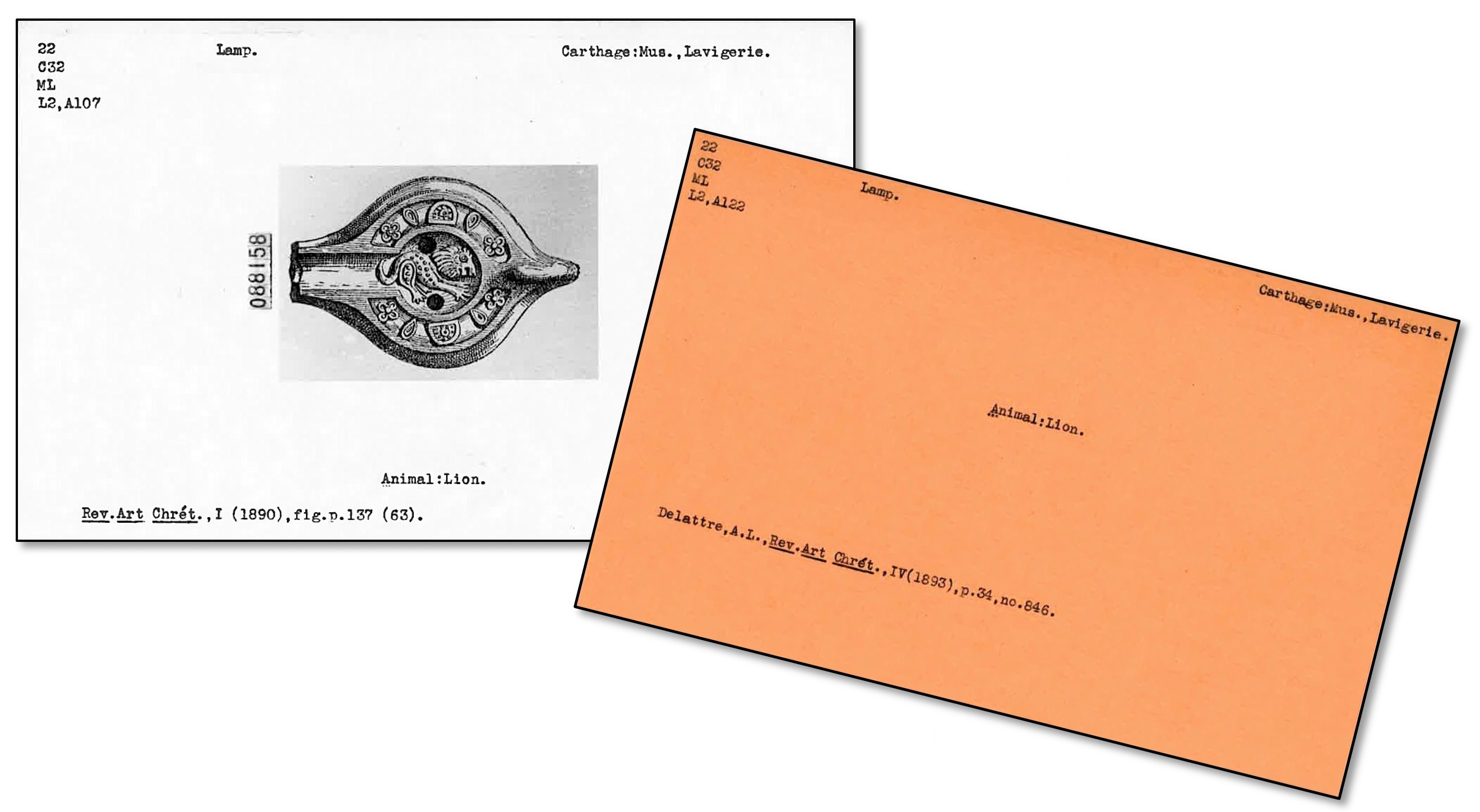

Under the medium “Terra Cotta”—a mixture of clay and water that is formed and baked or fired—the Index records more than twenty-five hundred objects across 196 locations. Of these objects, about sixty-five percent of them are oil lamps. The inventory of these files revealed some of the more common iconographic motifs found on terracotta objects, which include foliate ornament, a variety of land animals and birds, symbols such as crosses, as well as inscriptions and monograms. One terracotta lamp from the Benaki Museum in Athens depicts two of these popular motifs—a lion and a tree—combined on one impressed discus (Fig. 1).

Most photograph cards contain representations of the objects, but they also record the object’s location, the photograph’s negative numbers, subject headings for the image or images on the object, and some bibliographic information. However, there are many temporary “Orange Cards” in the archive that contain only a bibliographic reference and a subject term, and these still await corresponding images. Their inclusion in the original system nonetheless provides important data points about the objects they describe, laying the groundwork for future cataloguers to source the images for these object records. For example, the Index’s photo archive of terracotta objects in the National Museum at Carthage is mostly Orange Cards because the original Index records of these objects derive from a 19th-century publication with very few illustrations. While it would be useful to see images of the “lions” held at the National Museum in Carthage, even in the absence of photographs it may be just as useful to know that, of the 970 terracotta lamps held in that location, nearly four hundred depict animals, and about sixty-five of those include a lion.

A Face in Gold Glass

The “Gold Glass” files record over 650 objects across sixty-three locations dating mostly from late antiquity between the 3rd and 7th centuries. Of these objects, nearly half are vessels of some kind. Gold glass developed as a medium in the ancient Roman and Hellenistic periods and consisted of decorative engravings made in gold leaf, which were then sandwiched between fused layers of glass. The result was lavish decoration, and exemplary pieces in this medium offer strikingly detailed portraits of their subjects, often depicting married pairs, family groups, or religious figures associated with one another, such as Saints Peter and Paul. Historians have noted the rarity of gold glass, as well as its costly, specialized method of production.[1]

Gold glass was a special interest of Index founder Charles Rufus Morey, and his pioneering catalogue of the Vatican Library’s collections features as its first entry an example also catalogued by the Index. It shows the busts of a married couple inscribed above with the name Gregori and a Latin equivalent of “cheers!”: “Gregori bibe [e]t propina tuis,” or “Gregory, drink and drink to thine!” (Fig. 2).[2]

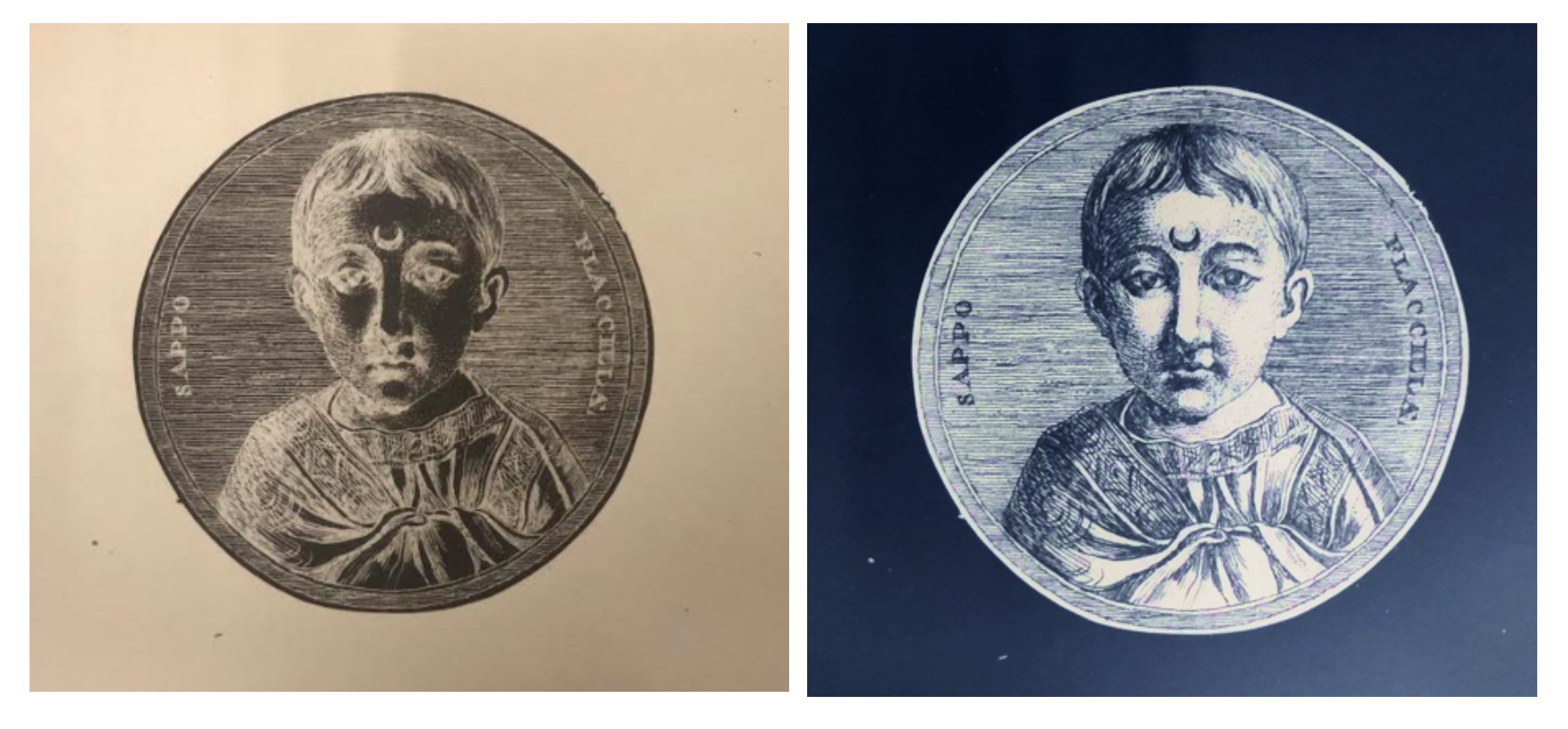

Another interesting discovery in the “Gold Glass” category was a round vessel fragment last recorded in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris. It depicts a striking bust of a figure with shorn hair, dressed in a trimmed tunic, and with a distinctive crescent shape on their forehead. The only other information on the photograph card was the source of the image, the antiquities catalogue that Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus published in seven volumes from 1756 to 1767.[3] Caylus’s catalogue was a valuable starting point for identifying this figure, whose iconographic description had not been entered in the Index’s subject files or the database. A little more searching led to a color image in a French catalogue, the Histoire de l’art de la Verrerie dans l’Antiquité (Fig. 3), and to the conclusion that the inscription “SAPPO FLACILLAE”—with the genitive form of the empress’s name—referred to a branded enslaved person who had been freed by the Roman Empress Aelia Flacilla (356–386). We also used the photo-editing web application Pixlr to create a positive image of “Sappo” so that the image from the Index archive can now be seen as it appeared in the catalogue of the comte de Caylus (Fig. 4).

Impressions in Wax

Comprising a little over one thousand objects in 105 locations, the “Wax” medium files are overwhelmingly made up of stamps from Europe dating largely to the 13th and 14th centuries. Although the archive groups these objects into the single object category “Stamp,” the Index database divides them into two Work of Art Types, “Seal Matrix” (that is, the tool used to make the impression) and “Seal Impression” (that is, an impression made by a matrix).[4] Viewing about a thousand examples of Gothic seals intended for both religious and secular officialdom brought into literal relief the development of the production of seal dies from simple figural representations to complex ecclesiastical chapters in miniature, such as the Stamp of Ely Priory, dated to about 1240–1260 (Fig. 5). Other favored subjects in wax seals include heraldry, nobles, and popular saints and bishops, like Thomas Becket. The wealth of iconographic information in the “Wax” files—indeed throughout the archive—emphasizes that the Index is not a closed system, and has at every turn great potential for leading one into new areas of inquiry.

Ryan Gerber is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. He holds an MA in English from The College of New Jersey with a concentration in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. His interests include digital preservation and retrieval, the digital humanities, and information behavior.

See Part 2 written by Michele Mesi.

[1] Giulia Cesarin, “Gold-Glasses: From their Origin to Late Antiquity in the Mediterranean,” in Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millennium AD (London: UCL Press, 2018), 22–45.

[2] Morey noted of the inscription that “the E of ‘bibe’ or of ‘et’ [was] omitted by mistake.” Charles Rufus Morey, The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1959), 1. Translation after Georg Daltrop in Leonard von Matt, Georg Daltrop, and Adriano Prandi, Art Treasures of the Vatican Library (New York: Abrams, [1970]), 168.

[3] Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus, Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, greques, romaines et gauloises (Paris, 1756–57), 193–205, pl. 53.2, https://archive.org/details/recueildantiquit03cayl/page/n10.

[4] See the Index database Work of Art Type browse list to access these Work of Art References.

Precious Gems Containing a Wealth of Iconography

“Glyptic” is among the smaller medium categories in the Index archive, filling only one drawer with a little more than eleven hundred cards that record only about nine hundred objects. The term “glyptics” refers the art of carving gems or seals—whether in intaglio or in relief—typically in gems or precious stones such as jasper, agate, carnelian, and amethyst.[1] This form of art is one of the oldest—known since the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Assyrian civilizations—but it was not until the Hellenistic period that relief cameos, seals, and more intricate glyptic objects began to appear.[2]

Glyptics, which were often worn as jewelry or incorporated into ecclesiastical objects, are recorded in the Index primarily as gems, amulets, plaques, rings, and stamps, and the largest category, cameos, which makes up nearly a third of the glyptic objects in the Index files. A significant portion of the subjects on these carved gems include animals and plant life, like doves, dolphins, fish, palm trees, and fantastic creatures. There are other symbols as well, such as the anchor, which appears on over forty examples. A significant number of glyptics incorporate classical and mythological figures, such as Orpheus, Diana, Jupiter, and Hecate. Nearly twenty cards for gem objects record the Gnostic figure Abrasax (Fig. 1). Glyptics such as these were powerful talismans for their owners.

The traditional use of spiritual amulets was also adopted by Christians using Christian symbols and themes.[3] Christian iconography on glyptics include the triumphant Archangel Michael or Saint George, Daniel in the Lion’s Den, and the Good Shepherd. One cameo of opaque black glass made in the 13th century depicts Saint Theodore transfixing the dragon and well represents the preference for saintly imagery on later cameos (Fig. 2).[4] The inventory also revealed that there were nearly thirty examples of incised depictions of monograms on glyptics with a third of them being the Chi-Rho, a symbol for Christ consisting of the first two letters of the word “Christos” (Christ) in Greek.

The major collections represented in this medium include the Staatliche Museen in Berlin (over eighty objects) and the British Museum in London (nearly 125 objects. However, a large number of glyptics (over 140 objects) are recorded as “Location Unknown,” these items having been entered into the Index from major publications that did not provide the precise location at the time of publication.

Radiant Ivories for Both Secular and Religious Narratives

With nearly forty-seven hundred cards covering a little over thirty-one hundred objects, Ivory represented a more extensive category in this inventory project. The types of ivory objects recorded by the Index range from plaques, chess pieces, croziers, and triptychs to the more unusual oliphant (or hunter’s horn) to the handles of various utensils, and even a saddle. Some of the major collections represented in this medium are the Musée du Louvre and the Musée de Cluny in Paris, and the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Ivory objects were expertly carved in minute detail, usually from the tusks of elephants. In the Index database, ivory acts as a “parent medium,” an umbrella covering such materials as bone, walrus tusks, and antlers.[5]

Various motifs of courtly love were often depicted on ivory caskets, plaques, mirror cases, combs, and other fine domestic objects.[6] A preference for secular subjects on ivories emerged in the twelfth century when an influx of secular imagery was brought to Europe from the Middle East after the Crusades, as well as through a rise in vernacular literature, legends, and romances.[7] Entertaining stories such as the tale of the Virgin and the Unicorn provided plenty of thematic material to adorn precious ivory objects. They often offered a double meaning or moral lesson, as in the story of Tristan and Isolde depicted on an early 14th-century ivory casket now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which warns against temptations of lust (Fig. 3).[8]

Despite their popularity, secular ivories are fewer in number than devotional works of art in ivory. Roughly a quarter of the ivory objects recorded in the Index are representations of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. This figure rises to more three quarters when we add individual figures of Christ or the Virgin Mary. One type seen rather frequently is that of the Virgin nursing the infant Christ—known in Latin as the Virgo Lactans—which the Index categorizes among the many “types” of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. In the database, the subject heading Virgin Mary and Christ Child, Suckling Type is attached to over 290 Work of Art records. More than forty of these are ivory. This Virgo Lactans iconographic type is exemplified by a 14th-century ivory statuette in the Yale University Art Gallery, which displays an intimate and lifelike relationship between mother and child (Fig. 4). Thus, the devotional message is made personal.

The Project Continues …

Encompassing eight drawers of roughly one thousand cards each, “Painting” proved to be an abundant medium, but “Illuminated Manuscript” is by far the largest medium category in the Index, filling fifty-six of the photograph drawers. Medieval art objects encountered in these two categories range from painted icons and altarpieces to a wide variety of liturgical manuscripts and other illuminated books numbering perhaps in the thousands. The inventory of these and other remaining categories—including those comprising in situ works of monumental art, such as “Mosaic” and “Fresco”—will continue after this summer.

As a “living archive” that covers more than a millennium of artistic creation, the Index of Medieval Art has always been improved and expanded by the interactions of the cataloguers who create it with the with researchers who use it. Creating these inventories has been an illuminating way to participate in that process and to learn more about the contents of the Index card catalogue being prepared for entry into the online database. This project was challenging at times, due to the sheer breadth of the paper files, but it has been an invaluable undertaking for the ongoing process of research and digitization, and will improve accessibility to the records contained in this century-old archive of medieval art.

Michele Mesi is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. From Rutgers University, she also holds a Bachelor’s degree in English with studies in Art History and in Digital Communication, Information, and Media. Her interests include art conservation, archival processing, and working with rare books and manuscripts.

See Part 1 written by Ryan Gerber.

[1] The Index of Medieval Art follows the standards for material description established by the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). See the Art & Architecture Thesaurus® Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/.

[2] O. Neverov and A. Durandin, Antique Intaglios in the Hermitage Collection (Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1976), 7.

[3] Neverov and Durandin, Antique Intaglios, 8.

[4] The Index records the iconography in question as Theodore Tyro or Theodore the General, Slaying Dragon.

[5] See the glossary entry on the Index database Medium browse list for “ivory.”

[6] J. Lowden and J. Cherry, Medieval Ivories and Works of Art: The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario (Art Gallery of Ontario, 2008), 122.

[7] R. H. Randall, “Popular Romances Carved in Ivory,” in Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age (Detroit Institute of the Arts, 1997), 63.

[8] Randall, “Popular Romances,” 67–68.

Detail, Arch of the Transfiguration Apse Mosaic, 6th century.

Church of the Transfiguration, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt

Location, Location, Location: In-Situ Iconography within the Medieval Built Environment

55th International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo MI, May 7-12, 2020

Proposal Deadline: September 15, 2019

Please consider submitting a paper to the next Index-sponsored session at the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo! This year’s session concerns the role of iconography within the built environment and has been organized by Index specialist Catherine Fernandez.

Session description: Almost all architectural components in the Middle Ages had the potential to bear images. Walls, arches, portals, domes, capitals, and other structural supports proffered surfaces for the deployment of narratives, portraits, drolleries, and ornament. Iconography in such locations not only figured prominently in relation to ephemeral occurrences, such as the performance of the liturgy, processions, and other civic rituals; it also underscored more permanent demarcations within urban cityscapes and rural landscapes by recalling specific events or established cultural or environmental conditions, both historical and legendary. This session invites proposals that explore the integration of in-situ iconography within the medieval built environment. We welcome papers that consider the relationship between the location of imagery within a monument and related external factors such as ritual, topography, patronage, institutional or civic memory, and regional identit(ies). Papers may consider specific case studies or address more theoretical concerns.

Please send abstracts of no more than 300 words with a completed Participant Information Form (https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/submissions) to caf3@princeton.edu) by September 15, 2019.

Further information about the Congress can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress

Information on awards granted to defray the travel costs of speakers can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/awards

The ways in which scholars research the iconographic traditions of the Middle Ages is continuously evolving. In order to address this, the Index of Medieval Art organized and sponsored a roundtable, Encountering Medieval Iconography in the Twenty-First Century: Scholarship, Social Media, and Digital Methods, at the 54th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. The five panelists briefly presented on the ways in which they incorporated iconography into their teaching, research, and curatorial work. They then participated in a discussion of how they use and develop online resources, such as image databases, to reach students and researchers. The result was a lively dialogue about how digital approaches can make medieval iconographic study more accessible to a diverse, global audience.

One of the first topics of discussion was the avenues by which viewers encounter medieval iconography in the twenty-first century. Anne Stanton, Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Missouri, raised the point that popular social media outlets and online databases are often the first portals through which many students gain access to medieval images and learn about subject matter in works of art. Many institutions have responded to this this fact by using social media platforms to broaden interest in iconography and connect users to works of art. The many vibrant examples of social media use in the field, ranging from museums to libraries, include the Getty, Dumbarton Oaks, and the British Library. Sabine Maffre, Curator of the Mandragore Database at the National Library of France, discussed developments at the library’s blog Gallica, which has been inviting professional bloggers to write posts about illuminations in order to diversify their audience and make their medieval image collections more visible.

Beyond questions of access, another change has occurred in the ways in which we think about iconography. Konstantina Karterouli, postdoctoral fellow and graduate of Harvard University, presented an Artificial Intelligence (AI) project that the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection is developing with the goal of teaching computers to recognize the different architectural elements of a medieval building. Commenting on the wider potential of this approach, Maffre also noted that the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) staff have been working toward implementing automatic recognition of manuscript illuminations through AI. A contrasting approach to iconography, presented by Isabelle Marchesin of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA) at the Sorbonne in Paris, faces head-on the problem of offering something that AI still cannot provide: interpretations of specialized content. The OMCI (Ontology of Medieval Christianity in Images) project, founded and developed by Marchesin, is based on the concept that, beyond narrative and portraits, Christian medieval images implicitly refer to another level of signification that is ontological and strongly connected in this case to theology as a holistic system of explanation of the world.

One important takeaway from the roundtable was the recognition that the role of the iconographer itself is changing. As Professor Marina Vicelja of the University of Rijeka emphasized, rather than requiring the solitary work so often undertaken in the past, it could and should be seen in light of collaborations, interdisciplinary research, and international networks. A starting point could be the implementation of cross-discoverable databases, shared standardized vocabularies, and the use of platforms like Biblissima, a digital library and widely interoperable data cluster designed to gather and give access to the main iconographic and textual databases. These ideas inspired discussion of the difficult balance between the strategies used by database specialists and the kinds of usability expected by twenty-first century researchers. Karterouli strongly emphasized the importance of standardization in these endeavors to help retrieve information, and Vicelja stressed the necessity of integrating metadata in order to avoid misunderstandings.

In the twenty-first century, we find ourselves at a crossroads between traditional methods of iconographic study and the implementation of pioneering technologies such as AI. The potential for interoperable platforms to enhance the research experience could answer new expectations with new possibilities. While it can be difficult to strike a balance between time-tested approaches and new ideas, the tension is proof that the study of iconography is very much alive and evolving. We hope that the Index roundtable at Kalamazoo was only the first word in a vibrant and expansive dialogue among an international community of creators and consumers of information about medieval iconography.

Please join the Index of Medieval Art for a one-day conference that examines the role of the visual in the negotiation of medieval power relationships, whether political, social, religious, or individual. Eight scholars with a range of specializations will address how works of medieval art were used to impose and maintain power over others, to resist dominant figures or regimes, or as agents in the back-and-forth of an ongoing power struggle. Speakers will include:

Heather Badamo, University of California, Santa Barbara

Elena Boeck, DePaul University

Thomas E.A. Dale, University of Wisconsin

Martha Easton, St. Joseph’s University

Eliza Garrison, Middlebury College

Anne D. Hedeman, University of Kansas

Tom Nickson, Courtauld Institute of Art

Avinoam Shalem, Columbia University

106 McCormick Hall, Princeton University

Organized by Elina Gertsman and Vincent Debiais and hosted at the Index of Medieval Art

Focusing on the long and rich tradition of nonfigurative art, this international symposium will explore the inception and transformation of abstraction(s) at various historical pivot points between the advent of Christianity and the interrogation of epistemological queries in the later Middle Ages. The symposium aims to introduce the concept of abstraction to the field of premodern art and redefine it as a visual structure that predicates the very nature of image-making. We seek to interrogate non-figurative forms in medieval material culture; to contextualize these forms within the contemporaneous cultural and philosophical discourses; to identify the common features that favor the emergence of abstraction specifically in the long Middle Ages; and to determine how abstraction has been used to make visible what is beyond any kind of representation. For the full schedule, click here.

Registration is free but required to guarantee seating.

The conference is co-sponsored by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the French-American Cultural Exchange Foundation, the Index of Medieval Art, Case Western Reserve University, and the École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

Eclecticism at the Edges: Medieval Art and Architecture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Cultural Spheres c.1300–c.1550

On April 5-6, 2019, the Index will co-host “Eclecticism at the Edges: Medieval Art and Architecture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Cultural Spheres,” along with the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, the Department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University, The Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Stanley J. Seeger Hellenic Fund, the Mary Jaharis Center for Byzantine Art and Culture, the International Center of Medieval Art, and the Society of Historians of East European, Eurasian, and Russian Art and Architecture. This two-day symposium focuses on the art, history, and culture of Eastern Europe between the 14th and the 16th centuries .

In response to the global turn in art history and medieval studies, “Eclecticism at the Edges” explores the temporal and geographic parameters of the study of medieval art, seeking to challenge the ways in which we think about the artistic production of Eastern Europe from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries. This event will serve as a long-awaited platform to examine, discuss, and focus on the eclectic visual cultures of the Balkan Peninsula and the Carpathian Mountains, the specificities, but also the shared cultural heritage of these regions. It will raise issues of cultural contact, transmission, and appropriation of western medieval and Byzantine artistic and cultural traditions in eastern European centers, and consider how this heritage was deployed to shape notions of identity and visual rhetoric in these regions that formed a cultural landscape beyond medieval, Byzantine, and modern borders.

You can view the program here.

The symposium is free, but registration is required to guarantee seating. For any queries, please contact the organizers at eclecticism.symposium@gmail.com.

NB: This satirical post was shared in celebration of April Fool’s Day 2019.

From time to time, we Indexers like to lift the veil, so to speak, on the cataloguing procedures and upgrades that we have undertaken online. One of our current priorities is filling out our Subject Authority records. These records are where researchers can find further information about a given iconographic subject, including the preferred term used by the Index for that subject and a brief description of the iconography, its main attributes, and its relevant cultural details.

We know that visitors to the database may use alternate names, spellings, or related terms for a particular subject during a search query, and we’re determined to help you find them. As we Indexers like to joke, one scholar’s Maiestas Domini is another scholar’s Christ in Majesty! (rim shot) It is for this reason that we supply a field for “See-From” terms, a list of alternate names and phrases that will redirect you to the preferred Index iconographic term.

Below is a sampling of our newest subject authority terms offered as an overview of our work methods, as well as a sense of where our field is heading with regard to iconography.

NAME: COCONUT

Note: Aural method of riding in medieval Britain that consisted of banging two empty halves of coconuts together to mimic the sound of horse hooves. Nota bene: the coconut is not indigenous to the region and likely arrived due to the migratory practices of the African Swallow.

See-Froms:

NAME: FRENCH PERSONS

Note: Surly Gallic individuals speaking with outrageous accents and serving Guy de Loimbard, possessor of “a” Holy Grail. Experts in deploying taunts at their enemies.

See-Froms:

NAME: LIVESTOCK (ARMS AND ARMOR)

Note: Favored weaponry of French Persons, comprising cows, geese, and other assorted farm animals to be hurled over castle walls.

See-Froms:

NAME: KNIGHTS WHO SAY “NI!”

Note: Darkly-clad knights wearing helmets bearing cow horns, keepers of the sacred words “Ni,” “Peng,” and “Neee-Wom.” Those who hear them seldom live to tell the tale. Lovers of ornamental garden elements that are nice and not too expensive.

See-Froms:

NAME: RABBIT OF CAERBANNOG

Note: A deceptively cuddly rabbit who is a foul, cruel, and bad-tempered thing. It guards the entrance to the Cave of Caerbannog, home to the Legendary Black Beast of Arrrghhh.

See-Froms:

NAME: HOLY HAND GRENADE OF ANTIOCH

Note: One of the sacred relics created to “blow thine enemies into tiny bits.” Instructions for its use found in the Book of Armaments 2:9–21.

See-Froms:

NAME: CASTLE ANTHRAX

Note: Castle with admittedly not a good name but possessing beds that are warm and soft and very, very big. It houses eightscore young blondes, cut off from the rest of the world with no one to protect them. These females enjoy bathing, dressing, [SCENE, OBSCAENA], making exciting underwear, [SCENE, OBSCAENA], and after [SCENE, OBSCAENA], [SCENE, OBSCAENA]. *

See-Froms:

* Note from the Editors: Given our reputation as a family-friendly blog, we have decided to redact this particular authority record. To that end, we have dusted off the Index’s trusty early twentieth-century subject heading “Scene, Obscaena.” As you readers are well aware, Latin makes everything sound more modest. The cataloguer responsible has been sacked.

Angels often function as messengers of God in the Bible. Perhaps the best-known example of this is Gabriel’s role in the Annunciation, a subject catalogued over two thousand times in the Index. He is identified by name in Luke 1:19, which describes him as saying “I am Gabriel, who stands before God…” as he brings word to the Virgin Mary that she will bear the son of God.

The story of the Annunciation and Gabriel’s part in it appears in the gospel of Luke 1:26–38. It recounts how God sent Gabriel to Nazareth to the home of the Virgin Mary. There, the archangel announced “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with you: blessed are you among women” (Ave gratia plena; Dominus tecum; benedicta tu in mulieribus) found in verse 28. The reason for this greeting appears a few lines later in verse 31: “…for you have found grace with God. Behold you shall conceive in your womb, and shall bring forth a son….” In verse 35 Mary, as yet unmarried, learns how this will come about: “The Holy Ghost shall come upon you, and the power of the Most High shall overshadow you.”

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Annunciation was depicted with varying degrees of complexity, and the means by which Gabriel brings his news varies as well. On the central portal of the Reims cathedral west façade (1245–1255), two statues of Gabriel and Mary stand next to each other, Gabriel smiling happily, Mary pensive. Here Gabriel offers nothing beyond a cheery expression, and very probably a gesture of blessing with his now-missing right hand. Yet the story was familiar enough that the two principals in close proximity would have triggered the memory of the Annunciation story for the viewer.

In the slightly more elaborate scene from a sixteenth-century Gradual in Princeton University Library (Princeton 11, fol. 2r), Gabriel approaches from the left, with his right hand holding a scepter, a reference to kingship, and with his left hand indicating the dove of the Holy Spirit hovering above Mary’s head. No words are exchanged. Gabriel’s verbal message is implied by his symbolic scepter and gesture.

Gabriel’s message is more overt in a highly detailed Annunciation image in an elegant fifteenth-century Book of Hours in the Morgan Library (M.893, fol.12r). The Trinity is present—God appears in a foliate medallion at the upper left, generating rays on which a mini Christ Child, carrying a wooden tau cross, glides downward. At the end of the rays, the Holy Spirit, again in the form of a dove, approaches Mary’s head. She observes this scene with some trepidation, raising her left hand as if to stop all this activity. At left, Gabriel holds a scroll inscribed Ave gratia plena dominus tecum benedicta tu in meenlieribus (sic). Mary is kneeling at a draped prie-dieu, her right hand resting on an open book lying on a pillow, emphasizing her piety, while at right in a niche is a vase with a stem of lilies evoking her purity. The plethora of symbolic forms suggest that the message is being fulfilled at the same time as Gabriel is delivering it, even as Mary’s raised hand says “I am not worthy.”

Gabriel bears his message in an unusual and possibly unique way in the Morgan Library copy of the Concordantiae caritatis (M.1045, fol. 7v). The text of this manuscript was originally written by Ulrich von Lilienfeld, a Cistercian monk in Lilienfeld, Austria, sometime between 1351 and his death in 1358. It is a typological text relating saints’ lives, Old and New Testament topics, and moralizing texts about nature. The manuscript provides sermon material, and is arranged in the order of the church year. The Morgan copy was written and illuminated in Austria in the third quarter of the fifteenth century.

In the Concordantiae Annunciation, the Virgin Mary appears to be kneeling, holding an open book with both hands. A dove descends toward her head as she looks back over her left shoulder. Her gaze is directed toward Gabriel, who kneels, both hands extending a partly folded document bearing three columns of pseudo-writing and three seals hanging from its lower edge. Why is Gabriel shown with this very unusual attribute?

The answer may lie in the special format of Gabriel’s document, which resembles that of legal documents in the Middle Ages. The agreement was written on the page itself, while seals appended to the bottom served as the signatures of the parties involved in the contract. The number of seals depended on the number of individuals taking part. Since three seals appear here, it is not a great leap to imagine them representing the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Is Gabriel delivering a signed contract to Mary, with the particulars outlined in three columns above the seals? Exceeding the traditional verbal greeting with which he communicates that Mary will become the mother of God, Gabriel here delivers a hard copy of a binding compact, leaving her no option but to accept.

Judith K. Golden, Art History Specialist

When the Index of Medieval Art launched its new online database application in 2017, we were excited that its modernized, user-friendly design would make our data more accessible to both experienced and neophyte researchers. We hoped also that moving to a proprietary, cloud-based design would lower operating costs, making the Index more financially accessible as well. And indeed it did: in our first year, we were able provisionally to lower institutional and individual subscription fees by one third and have seen subscription numbers rise as a result.

We’re now delighted to announce that as of July 1, 2019, we’ll be able not just to let the new rates stand, but to lower both subscription fees further by another $100, setting institutional fees at $850 and individual fees at $250 per annum. We hope that this further reduction, while modest, helps to bring the resources of the Index within reach for more researchers at a time of increased financial pressure on humanities scholars globally.