Index staff have been busy at the Index working on a variety of projects and launching free public access to the database, which officially opened on July 1, 2023. It has been wonderful to see a warm reception from researchers, and recent user statistics show that the Index database is reaching hundreds of unique users per day.

We will continue offering Zoom tutorials and the next one is planned for the Spring 2024 semester. If you have been wondering how to get the best results out of your searches and see more about what the Index covers, please stay tuned for the next date, or write to us directly with your research inquiry!

We’re still accepting applications for the student travel grant award to attend this year’s Index conference in person (Deadline, 1 October 2023). Up to $500 will be reimbursed for a non-Princeton graduate student who wishes to attend the conferences but lacks the financial resources to do so. To see the full eligibility and apply, follow this link: https://ima.princeton.edu/graduate-student-travel-grant/.

The Index conference “Whose East? Defining, Challenging, and Exploring Eastern Christian Art” will take place on Saturday, 11 November 2023 in Julis Romo Rabinowitz A17 at Princeton University from 8:45am to 5:15pm (EDT).

Please note registration is not needed to watch the livestream, and the conference will be broadcast live at this link: https://mediacentrallive.princeton.edu/.

Please save the date for the next Index of Medieval Art conference, “Whose East? Defining, Challenging, and Exploring Eastern Christian Art” on November 11, 2023.

This conference asks how the concept of “the East” has shaped perceptions of Eastern Christianity generally and Eastern Christian Art more specifically, in Euro-American scholarship as well as in the popular view. Building on or dismantling such historical divisions as Western/Eastern Roman Empire, Latin/Orthodox, or simply East/West, speakers will explore what “East” and “East Christian” mean, how the boundaries of these concepts changed over time, and where exactly are the edges of the geographic, political, and religious “East.” This conference will offer a new understanding of the eastern Christian world by examining its cultural production in its own right and demonstrating that its rich, complex, and significant artistic production was not at the periphery of somewhere else, but rather at the center of an interconnected world.

The conference will focus on the regions of medieval Syria, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe. These territories are often neglected in medieval and early modern scholarship as regions that are merely “East” of somewhere more important. The material culture produced in the regions “east” of Western Europe—such as modern-day Ukraine, Serbia or Romania, to mention only a few—has for a long time been considered of “lesser” value or importance compared to France or Italy; the Caucasus is often considered only in relation to Byzantium; and art produced in Armenia, Georgia and Anatolia has often been discussed in terms of a center/periphery dichotomy. Rarely is the visual production of these areas allowed to speak for itself.

Speakers will include:

Anthi Andronikou (University of St Andrews)

Breaking Free from Bias: Eastern Christian Art between the Islamic and Western Worlds

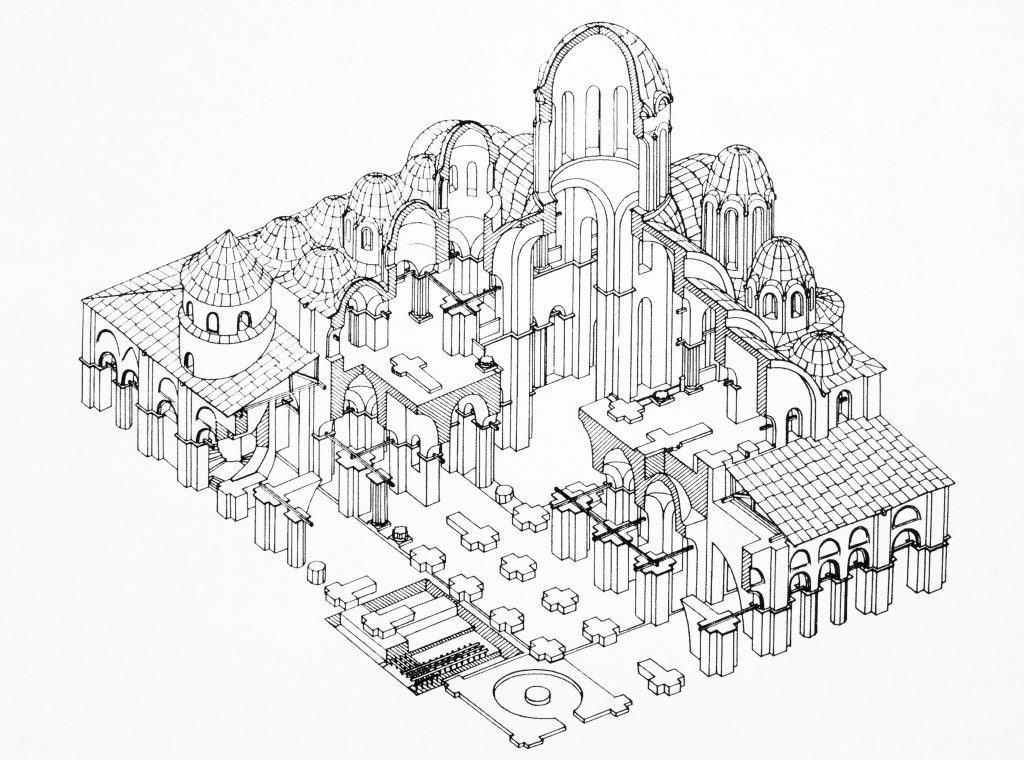

Jelena Bogdanović (Vanderbilt University)

On Theory and Architecture in the Medieval Balkans

Jana Gajdošová (Sam Fogg)

Byzantium and the Court of Emperor Charles IV in Prague

Gohar Grigoryan (University of Fribourg)

The East-West Paradigm in HighMedieval Armenia: The Evidence of Polemical Writings and Visual Sources

Christian Raffensperger (Wittenberg University)

A Third Category: Rus in History and Art

Erik Thunø (Rutgers University)

Nobody’s East: The Interconnected World of South Caucasian Cross Steles

Tolga Uyar (Nevsehir Haci Bektas Veli University)

Thirteenth-Century Monumental Painting in Cappadocia: The Artistic Bonds between Byzantium, Seljuk Rūm, and Eastern Mediterranean World

Margarita Vulgaropoulou (Ruhr-Universität Bochum)

Whose Adriatic? Blurring theBoundaries of East and West in the Artistic Production of the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic

Respondents:

Antony Eastmond (Courtauld Institute of Art)

Mirela Ivanova (University of Sheffield)

The conference will be hosted in person as well as live-streamed. The conference schedule, location details, and live stream registration link will be posted in September.

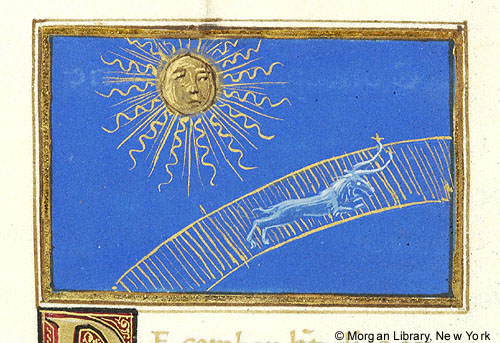

It’s May again, the month that marked the traditional beginning of summer in the Middle Ages. Much as it still is today, this seasonal turn was celebrated with festivals that set aside the toil of spring in favor of games and leisure. In medieval iconography, this time of the year is also captured in a variety of courtship scenes belonging to a genre known as “courtly love.” Such scenes sometimes represented the month of May with depictions of couples playing a game of chess or setting out on horseback for the sport of falconry and hunting, as well as holding merry engagements around fountains or flowing springs. The typical zodiac sign associated with the month of May was Gemini, usually represented by a pair of either twins or lovers, which epitomized the idea of two for this time of year: a double, a match, and a mirror image.

The iconography of mirror and fountains is similar in its ability to emanate personal reflections of a viewer, which made them desirable themes to utilize in courtly imagery. While the idea of gazing at your “twin,” perhaps framed in a window or seated across a chessboard, was celebrated in the Middle Ages, looking at your own reflection for too long, or for the wrong reasons, was frowned upon. A classic warning appears in the tale adapted from Ovid’s Metamorphoses of the mythological Greek hunter Narcissus, who so loved his own reflection that he became fixated on it for life, rejecting all offers of love.

The Narcissus theme is represented in a late fifteenth century miniature in an English manuscript of the Confessio Amantis (“Confessions of a Lover”) by John Gower (d. 1408). The artist depicts a kingly Narcissus wearing a crown, a vair-lined garment, and a jeweled girdle while staring at his own reflection in a fountain (Fig. 1). Narcissus stands in a fenced enclosure surrounded by a unicorn, a collared dog, and a stag. The presence of the stag evokes an Aesopian fable with a similar message, usually called the “Stag and its Reflection” (or the “Proud Stag”), in which a stag admires his antlers in a pool for too long and is caught by the hunter. Like its captive animal companions, the stag echoes Narcissus’s enmeshment in his self-image and ties him to the fountain.

In the popular medieval romance known as the Roman de la Rose, by Guillaume de Lorris (fl. ca. 1230), the “Lover” (Amans) encounters the Fountain of Narcissus and is similarly drawn to look at the reflection of his face in the water (Fig. 2). Like Narcissus, the Lover in the Roman de la Rose is taken with his own beauty in the pool and leans over to admire it; but unlike that of Narcissus, the pool is also the “Fountain of Love,” which destined all who looked in to fall in love. Thus, the Lover’s self-reflection is deeper and more altruistic than his external features, allowing him to overcome the curse of vanity and experience an ideal transformation.

Among the most interesting imagery related to mirrors, fountains, and love is that on Gothic mirror cases, also called valves de miroir. Over seventy examples currently exist in the Index of Medieval Art database, and you can find them by browsing for “Mirror Case” under Work of Art Type. Such mirror cases would twist open to reveal a polished metal disk for personal reflection, while imagery on the closed case told an allegorical story linked with chivalric lore. Mirrors have been part of society since antiquity when they were first made of highly polished stones. The mirror is an essential tool in the iconography of the Toilet of Venus, and it also became both a virtuous attribute for the self-aware personification of Prudence and a sign of vice for that of Vanity. Yet the images carved on Gothic ivory mirror cases rarely warn about the dangers of selfish looking. Instead, they often present scenes of youthful love. On a mirror case in the Walters Art Museum, within the arched portcullis of a castle, a man cups the chin of a woman in a gesture called “chin-chucking” (Fig. 3).

On the Walters ivory mirror back, other young people engage in friendly activities while a group of disabled or elderly persons parade toward the waters of the allegorical “Fountain of Youth” seeking an immortalizing dip. A similar procession of four pairs of men and women meeting at a central two-tiered fountain issuing streams of water appears on a double-sided ivory comb in the Victoria & Albert Museum, made ca. 1400 (Fig. 4). Here, the couples do not gaze into the fountain, nor do they bathe in its restorative waters, but the fountain separates the groups into symmetrical pairs, suggesting an impending connection. The glossy surfaces of mirrors and fountains, with a myriad of possible reflections—of a person’s vanity or deep self-knowing, the promise and capture of love, or the hope of love as a soothing, restorative balm—made these water features the appropriate gathering places for courtly lovers.

The month of May can resemble December for those of us on the academic calendar. The buzz of the semester diminishes to a low hum; there are fewer events, fewer emails to answer, and fewer faces around campus as people take time away from university life. Some might take a break from their work to review their activities and reconnect to individual goals and missions. These yearly transitions can also be times of reflection. Wherever this summer takes you, for work or on trips to faraway lands, we wish you good health and safe travels!

Select Subjects of “Love” Interest in the Index of Medieval Art

The following iconographic headings can be accessed in the Index of Medieval Art Subject List:

Married Pair —The iconographic depiction of a husband and wife together, identified or not.

Marriage—A scene of matrimony or wedlock celebrating the union of two people as they become spouses.

Castle of Love—The “Castle of Love” allegory is associated with the iconography of chivalry and courtly love and is often represented on fourteenth-century ivory mirror cases and caskets. Also known as the Siege (or Attack) on the Castle of Love, it typically includes the God of Love (Eros or Cupid) holding a bow and arrow and positioned on the top of a castle while women, couples, and lovers defend the tower, sometimes by tossing roses on battling equestrian knights below.

Courting—Index subject incorporating various scenes of courtly love, including crowning lovers, or couples chin-chucking, also used in combination with scenes of falconry, hunting, or chess.

Couple—The term to describe a pair of people, usually a man and woman depicted as lovers.

Falconry—Also known as “Hawking.” The sport of hunting with predatory birds is especially associated with the iconography of the Labors of the Month for April and May and scenes of courtship with figures and couples holding the birds of prey.

Fountain of Love—An allegorical fountain for courting lovers as described by the fourteenth-century French composer Guillaume de Machaut.

Fountain of Youth—An allegorical fountain or spring which, according to legend, had the power to restore youth to anyone who bathes in its waters.

Labors of the Month, May—The occupation for the month for May, usually represented by an outdoor scene of courting or the sports of hunting and falconry, often by equestrian couples. Variants of this scene include the courting lovers walking in a landscape, sometimes holding hawks, falcons, flowers, or branches, or sometimes depicted in a scene of merriment involving musicians.

Mirror—A polished surface, often held by a handle or decorative frame, and reflecting a clear image of what it is pointed at. Attribute of the vice personification of Vanity. Sometimes held by the goddess Venus.

Sexual Activity—The subject for figures engaging in any explicitly sexual activity. Often suggested by two people lying down in close proximity to each other, possibly nude, possibly embracing each other, and sometimes in a bed.

Further Reading

Camille, Michael. The Medieval Art of Love: Objects and Subjects of Desire. New York: Abrams, 1998.

Hult, David F. “The Allegorical Fountain: Narcissus in the ‘Roman de la Rose.’” Romanic Review, 72, no. 2 (1981): 125–50.

Lewis, C. S. The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Peklar, Barbara. “The Imaginary Self-Portrait in the Poem Roman de la Rose.” Ars & Humanitas 11, no. 1 (2017): 90–105.

Other Resources

The British Museum. “A ‘Greatest Hits’ of medieval myths on a casket | Gothic Ivories 1 | Curator’s Corner S7 Ep4.” YouTube Video, 11:57. June 23, 2022. https://youtu.be/IA0sWopdLxs.

Gothic Ivories Project at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Accessed February 14, 2023. http://www.gothicivories.courtauld.ac.uk/.

This blog post is the seventh in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce Jon Niola.

What is your role at the Index?

I am the Information Technology Manager here at the Index. I manage the day-to-day technology needs of the Index. That includes everything from managing virtual machines on the cloud to deploying new computers for staff or writing code to enhance the accessibility of our web applications.

Before working for the Index, what was the most interesting job you had?

In the late 1990s I worked at a technology startup in New York City trying to improve Internet search. We used algorithms to make a search more appropriate to the context. For example, if you searched for the keyword “jaguar,” were you searching for the automobile or the animal? Our algorithms used recent searches and site visits to try and narrow the scope.

When you’re not working at the Index, what do you like to do in your spare time?

If the weather cooperates, I absolutely love to hike, and I spend quite a bit of time on the trail, getting some exercise and fresh air and enjoying the tranquility.

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. I had always planned on visiting it when I went to Paris, but to me it was just a bucket list, “must do” item. I never expected it to be so incredible in person. I had a few thousand dollars of camera gear with me, and no photo I took does justice to the beauty of it, especially the upper chapel with the incredible stained glass.

What’s your favorite building or spot to sit on campus?

This is a tough call. I can’t choose between Nassau Hall and the university chapel.

The chapel is beautiful, and at certain times of the day when the angle of the sun is right, you get these beautiful colors on the stone as the sun filters through the stained glass.

The history buff in me appreciates Nassau Hall. The fact that it once served as the capitol of the United States is fascinating to me. We are blessed with a lot of great local history.

Coffee or tea?

Yes. I often drink coffee in the morning, but I do love a good tea.

This blog post is the sixth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce Fiona Barrett.

What is your role at the Index?

My role at the Index is that of Office Administrator/Coordinator. The exciting part of my job, which is not at all traditional (in the administrative sense), is that I am able to assist where/when needed in the Index database and library. If you’ve seen the #IndexHumpDay posts on social media, you’ll see my weekly interaction with iconography—a variety of camels depicted across media, geographies, and time periods.

Before working for the Index, what was the most interesting job you had?

Before working for the Index, I worked in market research for twenty-five years, which—while interesting and challenging at times—in no way compares to my experience here at the Index. I’m very grateful to be exposed to all of this art history, and lucky enough to have colleagues who take the time to explain things to me when needed.

When you’re not working at the Index, what do you like to do in your spare time?

Hmm … a few of my favorite things: cooking, eating, entertaining, reading, gardening, traveling, listening to music (especially my husband’s 😊), and I love spending time with family and friends; they are one and the same.

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

I spent part of my childhood growing up in Ireland, but I truly didn’t appreciate the country and the history until I was in my early thirties. I was lucky enough to travel back a few times, with my father and then with my son. I would go again in a heartbeat! This year I am planning to travel to Italy, which has been on my bucket list for quite some time.

What do you like best about being back on campus in person?

Now that we’re back in person, and I am working with colleagues face-to-face, it’s great to be able to have our in-person conferences and workshops once again. This past conference—“Looking at Language” in November 2022—brought together over fifty attendees, and seven of the eight speakers were able to present in person.

Coffee or tea?

YES, PLEASE!

We are excited to announce that the mosaics of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv are now live in the Index database! Thanks to a Flash Grant from the Princeton University Humanities Council, Dr. Julia Matveyeva, Associate Professor in the Department of Fine Arts and Design of the O. M. Beketov National University of Urban Economy in Kharkiv, joined the Index remotely for the last five months to work on Ukraine’s medieval cultural heritage. Find out more about St. Sophia Cathedral, the work of an Index cataloger, and Dr. Matveyeva’s research at this link.

We are very pleased to announce that as of July 1, 2023, a paid subscription will no longer be required for access to the Index of Medieval Art database. This transition was made possible by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the support of the Index’s parent department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University.

When an online database of Index records was first launched in the 1990s, it was as a subscription service; only those affiliated with a subscribing institution or willing to pay for a subscription of their own could access the full online records. An opportunity to rethink this model arose in 2017, when our shift to a new, non-commercial database platform lowered costs enough that, with careful budget management, the subscription fees could be progressively reduced. In 2023, bridge funding from the Kress Foundation will allow us to eliminate fees entirely, giving researchers at all levels full access to the Index database at no cost, and ensuing support from the Department of Art & Archaeology will allow us to make this transition permanent. We express our deepest thanks to both the Kress Foundation and our department for their support of this initiative.

We look forward to working with the wide range of new researchers who will gain access to our resources, and in the coming months we will offer several online training sessions to introduce the database to those who may be unfamiliar with it. The schedule and signups for these will be publicized on this blog and through the Index social media accounts. Index staff also remain available at all times for researcher questions via our online form at https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/.

We hope that this good new brightens your New Year as much as it does ours, and we look forward eagerly to sharing our resources with students and scholars from high school to retirement, as well as with public learners seeking the reliable information about medieval art and culture that has always been the goal of the Index of Medieval Art.

The Index of Medieval Art will close at noon this Friday, Dec. 23. The reading room will open to visitors on Dec. 28 and 28 and then resume its normal weekly schedule (9 am to 5 pm, Monday through Friday) beginning Jan. 3, 2023. As the days grow longer and winter begins, we share our best wishes for a warm, bright holiday season and promising New Year.

In November 2022 the Index of Medieval Art was pleased to award a Graduate Student Travel Grant to Johann Spillner, a doctoral candidate at the University of London to attend the Index Conference “Looking at Language.” He sends this reflection on his experience:

“It is the sign of a great conference when every paper, no matter how remote to one’s own field of interest, holds your attention. “Looking at Language,” held by the Index at Princeton this November, was certainly a great conference and I count myself lucky to have been able to attend in person due to the generous support of a travel grant from the Index. The papers which addressed, among other things, updates of language in manuscripts (Benjamin C. Tilghman); misspellings in mosaics (Warren T. Woodfin and Ludovico V. Geymonat); or fictional objects in vernacular narratives (Kathryn Starkey) were thought-provoking throughout. The presentation that has stuck with me the most is the one by Prof. Margaret S. Graves on “The Limits of Language,” in which she discussed the art historical bias towards the “talkative” artifact and served as a poignant finale to all the previous papers. Among the things that are still only possible when attending in person (apart from ingesting the excellent food provided by the Index) were the conversations during and after coffee breaks and at luncheon—here, I have to especially thank Prof. Ruba Kana’an for some enlightening and thought-provoking chats.

“While the conference alone was well worth my eight-hour transatlantic flight, the second highlight of my trip was certainly visiting the Index itself. Having only seen the online portal of the Index, the actual library and card indices have left a deep impression on me. My own research tries to address the formative power of art historical categorization and language, and standing in the Index itself, I could not help but feel that the Index, through countless years of sweat and, I imagine, a lot of tears, was the physical manifestation of that trajectory. There is something to be said for getting lost in the Index’s system and diving into the countless rabbit holes that the card index offers. While I started by looking at images of Stylites—Christian ascetics who lived out their lives atop of columns and pillars—my interest was caught by a different category of persons positioned next to various building parts: the unnamed nineteenth- and twentieth-century “staffage figures” who give a sense of scale or local color to the photographs of in-situ monuments. These do not represent a category of their own in the Index, but one can imagine the countless stories encapsulated in these photographs.

“All this is to say that my research at the Index was a joyful and stimulating journey. At this point, I would like to thank the Index of Medieval Art, and especially Pamela Patton, Fiona Barrett, and Jessica Savage for the support and their kindness that enabled me to come to Princeton. Special thanks to Jessica Savage for not only sacrificing her time and patience to teach me the ins and outs of the Index system but also accompanying me on my aberrations during my stay.”

And the Index thanks YOU, Johann, for traveling to join us and for sharing your experience with our readers. We hope to see you again soon.

Johann Spillner is a PhD candidate at the University of London, Birkbeck College in the Department of History of Art. His research focuses on Islamic architectural objects in Western museums, more specifically, what their removal, display and representation mean for the subsequent reading of these objects.