On May 19-20, 2017, international and US Scholars will gather at Princeton to examine the near-intact monastic treasury of San Isidoro in Leon, in northern Spain, as a springing point for larger questions about sumptuary collections and their patrons across Europe and the Mediterranean across the Middle Ages. Topics of inquiry include Islamic law and sumptuary production, Christian manuscripts and metalwork, patronage and royal studies, identity and gender studies, and cultural and political history. The diversity of questions and perspectives addressed by the speakers will shed light on the nature of Leon as a paradigmatic treasury collection, as well as on the broad efficacy of multidisciplinary study for the Middle Ages.

Follow the link below for a full schedule and (free) registration information. We hope to see you there!

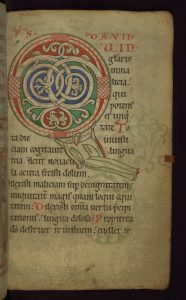

In medieval terms, March 25 was about as symbolically busy as a day could get. Already noted in the Julian calendar as the date of the vernal equinox, it is identified in the Golden Legend of the chronicler and archbishop Jacopo da Voragine as the date of an unusual number of auspicious Biblical events: Adam’s and Eve’s fall into sin; Cain’s murder of Abel; Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac; Melchisidek’s offering of bread and wine to Abraham; the martyrdom of John the Baptist; the deliverance of Saint Peter; the martyrdom of Saint James the Great; and the Crucifixion. Still more strongly associated with this date was the Annunciation, at which, according to Luke 1:26-28, the archangel Gabriel brought word to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive the son of God: “And in the sixth month, the angel Gabriel was sent from God into a city of Galilee, called Nazareth, to a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. And the angel being come in, said unto her: Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women.”

Gabriel’s announcement to Mary inaugurated the Christological narrative that governed all the feasts of the liturgical year, so it is unsurprising that this event should be highlighted in medieval calendars, where its proximity to the start of spring also led many to treat March 25 as the beginning of the new year.

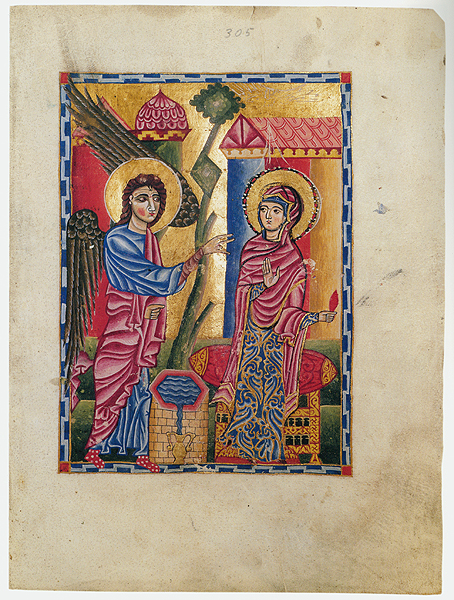

The Annunciation is among the most consistently depicted subjects in medieval iconography; it is found in everything from early Christian catacombs and sculpted facades to books of hours, mosaics, and panel paintings. Its composition and details vary in accordance with its setting: the Virgin might appear on a throne, in a loggia, in a bedroom, or outdoors, and she often is shown spinning or reading. A variant of particular interest is the depiction of the Annunciation at the Spring (as it is catalogued in the Index), also known as the Annunciation at the Well. Inspired by accounts preserved in early apocryphal texts such as the Protoevangelium of James and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, this variant depicts the Virgin greeted by Gabriel as she is fetching water, the first of two successive meetings in which the angel delivers his news.

The Annunciation at the Spring emerged in late Antiquity and flourished in Byzantium and the visual traditions close to it. An early exemplar appears on a fifth-century plaque, possibly a book cover, now in Milan Cathedral Treasury. Here, a small square scene of the Annunciation initiates the narrative of Christ’s life; it depicts the Virgin Mary kneeling by a stream, pitcher in hand, as she looks back to receive the angel’s greeting. In a much later manuscript example, a twelfth-century Homilies of James Kokkinobaphos (Paris, BnF, MS gr. 1208, fol. 159v), two meetings are implied: at left, Mary dips her pitcher into a well as she turns to hear Gabriel’s message; at right, she approaches a house where she will receive the angel a second time.

A more dynamic version of the well scene appears in an early fourteenth-century mosaic in the Church of the Savior at Chora in Istanbul: composed on a pendentive below one of the structure’s domes, it positions the angel as a fluttering visitor who descends the curved surface to greet Mary as she teeters over the well below.

Other cultures with close ties to Byzantine traditions also adopted the Annunciation at the Spring. The scene appears among twelfth-century mosaics of the Life of the Virgin in the transept of the church of San Marco in Venice, as well as in the early fourteenth-century Armenian manuscript known as the Glazdor Gospels (Los Angeles, University of California Research Library, MS. 1, p. 305).

In the Gospels manuscript, a flattened, stylized well and pitcher offer only a vestige of the original iconography as they stand between Gabriel and the Virgin. The figures’ static postures, animated only by Gabriel’s speaking gesture and the Virgin’s raised palm, recall western Annunciation scenes, but Mary’s gilded brocade and the ogival dome at the top of the composition attest to its eastern roots.

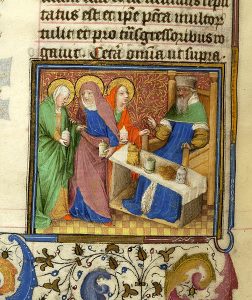

The medieval church season of Lent officially opened with Ash Wednesday, the Wednesday after Quinquagesima Sunday (the period of fifty days before Easter). The observance of Ash Wednesday marked forty fast days before Easter, not counting Sundays. During Lent, medieval Christians were forbidden to consume meat, eggs, dairy and animal fats, except on the permitted Sundays which were viewed as a “mini-Easter.” By adding a level of restraint to their daily lives, medieval Christians fulfilled a call for penance, which was especially important during the Lenten season. On Ash Wednesday, in the Middle Ages as it is now, a celebration of Mass incorporated the distribution of blessed ashes on the foreheads of believers. When dispensing the ashes, the celebrant reminds those receiving it that “as you are from dust, from dust you shall return” (based on Genesis 3:19).

The Index records three examples in manuscript illumination of the distribution of ashes. Each begins a part of a liturgical book read for this feast: a Gradual fragment in Princeton University Library (Kane 13), a Gradual in the Morgan Library (M.933), and a Missal in the Walters Art Museum (W.174). The Morgan and Princeton Graduals begin with the same Latin Introit, “Misereris omnium domine et nichil odisti eorum…” (Thou hast mercy upon all, O Lord, and hatest nothing…). It is interesting to note that the subject heading “Scene, Liturgical: Distribution of Ashes” used by the Index now was not in the original card file but was developed sometime during the last twenty years when post-1400 material was incorporated into the Index.

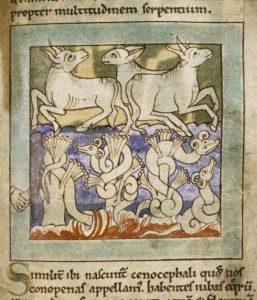

Episodes from the life of Saint Blaise: Saint Blaise living with animals; extracting the fishbone; restoring the pig, and martyred with steel combs. Vitae Sanctorum, Anjou, 14th c. (Bib. Vat., MS lat. 8541), fol. 52v.

February 3 in the Roman Catholic calendar and February 11 in the Orthodox one mark the feast day of Saint Blaise, Bishop of Sebaste in Armenia in the early fourth century. According to his hagiography, Blaise had been trained as a physician before becoming a bishop in the early Christian church, an institution still outlawed in the Roman Empire. Seeking solitary prayer in the wilderness, he lived peacefully with the wild animals until his arrest by Roman soldiers on the orders of the Roman governor Agricola, under whom he was imprisoned, tortured, and martyred. Blaise’s best known miracles include his restoration of a pig to a woman from whom it was stolen by a wolf who returned it on the saint’s command, and the cure of a boy who was choking on a fishbone. This second miracle resulted in Blaise’s designation as the patron saint of those suffering from throat ailments, inspiring the annual tradition of the Blessing of the Throats on Saint Blaise’s Day, also known in the west as Candlemas.

Saint Blaise before Agricola, detail of a stained glass window from the Soissons region, first quarter of the 13th c (Louvre, OAR 504).

In the Index of Christian Art, Blaise is catalogued as “Blasius of Sebaste.” He is typically depicted wearing his bishop’s robe and miter and holding a crozier. In later medieval art, he often holds a wool carder’s comb, perhaps a medieval reinterpretation of the Roman steel combs with which his flesh is said to have been raked during his martyrdom. Post-medieval images sometimes depict him holding two crossed candles in an allusion to the Blessing of the Throats. His most common narrative depictions show him meditating or ministering among the wild beasts; extracting the fishbone from the choking boy; standing before Agricola; or in the act of martyrdom, sometimes accompanied by the seven pious women who, according to Eastern tradition, followed him throughout his torments, wiping up his blood.

The marketplaces of medieval Europe were redolent of the spices that purportedly first arrived with returning Crusaders. A taste for the flavors of cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, ginger, pepper and the like created an increasing demand for spices that could not be grown in Europe’s climate but had to be imported from the East along secret trade routes, over land and sea. Distance was only one of several factors that affected the supply of spices, which were expensive and enjoyed only by those who could afford them. Nevertheless, as Paul Freedman writes in his blog “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced our World,” the new taste for exotic flavors helped encourage world exploration and turn spices into global commodities.

The uses of spices were both culinary and medical, and medieval cookbooks and herbals reveal that spices were part of preferred regimens. Spices were taken together in varying combinations, sometimes seasonal. In the cold and wet winter months, it was advisable to eat spices in strongly flavored food and drink to warm the body. Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat notes in her History of Food that the physician Arnau de Villanova (c. 1240-1311) recommended balancing the four humors of the body by consuming spices “proper for winter” as zesty sauces of ginger, clove, cinnamon, and pepper (Toussaint-Samat, 486). These spices would aid digestion after a heavy winter meal by heightening the effects of “hot” and “humid” properties in roasted meats. To this day, the warming spices advocated by Arnau de Villanova tend to be associated with fall and winter.

Cameline sauce, perhaps the original steak sauce, was the perfect accompaniment to roast meats. Prepared in summer and winter months alike, the sauce was so popular in some locations, such as fourteenth-century Paris, that the blend was usually readily available from the local sauce maker. There were regional varieties of Cameline sauce, too, and the “Tournais style” involved grinding together ginger, cinnamon, saffron and half a nutmeg. The spice powder was soaked in wine and stirred together with bread crumbs. The strained mixture was then boiled, with sugar added to make the winter variety of the sauce. One recipe for Cameline sauce has been adapted by Daniel Myers for the Medieval Cookery web site and is reproduced here with permission.

Cameline Sauce

3 slices white bread

3/4 cup red wine

1/4 cup red wine vinegar

1/4 tsp. cinnamon

1/4 tsp. ginger

1/8 tsp. cloves

1 tbsp. sugar

pinch saffron

1/4 tsp. saltCut bread in pieces and place in a bowl with wine and vinegar. Allow to soak, stirring occasionally, until bread turns to mush. Strain through a fine sieve into a saucepan, pressing well to get as much the liquid as possible out of the bread. Add spices and bring to a low boil, simmering until thick. Serve warm.

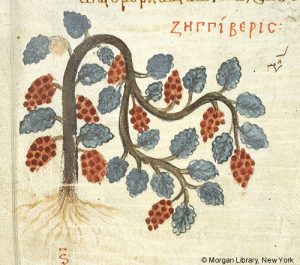

Ginger came to be highly prized during the Middle Ages, though the use of ginger can be traced back thousands of years in India and China. The potent ginger plant and rhizomes were valued for their stomach-warming and digestive properties as much as for the flavors they imparted. The first-century Greek physician Dioscorides advocated consuming a spicy Arabian plant called ζιγγίβερις (zingiberis), which was probably ginger, to “soften the intestines gently.” In Arabia, Dioscorides noted, they used only the freshest ginger plants (O’Connell 116-117).

Clove was known as one of the “lesser spices.” Though not as strong as ginger but useful for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties, clove was especially useful in dental care.

Named in English and other languages—“clou de girofle” in French—for the resemblance of the bud to nails, clove originated in the Moluccan Islands of Indonesia, the historical core of the Spice Islands. As with ginger, clove had its earliest uses in India and China in the fourth-century BCE, finding its way to Roman and Greek markets by way of port cities on the Mediterranean. By the eighth century, clove was known throughout Europe and features in several historic dishes. It was also a typical spice in pomanders, the medieval precursor to potpourri, in which fragrant ingredients were placed in a perforated box to ward off illness. The decorative use of clove-studded oranges, a seasonal pomander, is still associated with the winter months.

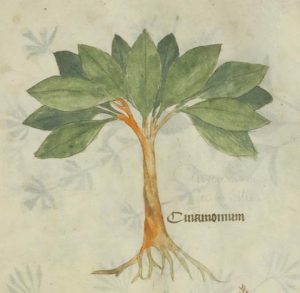

Hippocras, or hypocras, was a medieval spiced wine and popular cordial enjoyed especially during the winter holidays for several centuries. Hippocras was a concoction of powdered cinnamon, cassia buds, ginger, grains of paradise and nutmeg boiled with sugar and wine. Cinnamon, the essential flavor of hippocras, was a favorite spice of the medieval palate. Its mysterious origins generated many fanciful tales and even several expeditions. Perhaps most famously, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus thought he had located the spice in America—the Indies to him— and in 1493 he reportedly brought back bits of bark from a perfumed wild cinnamon tree that was not very tasty.

Long before Columbus, the ancient Egyptians had prized cinnamon as the “… goodly fragrant woods of The Divine Land…” while medieval Arabs believed that large birds used cinnamon sticks in their nests (O’Connell, 76-77). In the first century, the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder rightly located the origin of cinnamon on the shores of the Indian Ocean. With information from some seasoned merchant, perhaps, Pliny knew that the cinnamon trade was dangerous and that a return trip to the source of the spice took almost five years. Pliny’s claims about the origin of cinnamon were eventually verified in the 1340s when the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta (1304–c. 1368) arrived at the island of Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) and discovered untouched miles of the cinnamon tree. Before its widespread appreciation as a culinary ingredient, cinnamon was prized in several ancient cultures as incense holding ritualistic importance, sometimes burned for its fragrance on a funeral pyre.

The final “proper” winter spice is pepper. With a name widely applied to many spices, including the black and white varieties, pepper was perhaps the most familiar spice of the Middle Ages. Both black pepper and white pepper are obtained from the small berries of the Piper nigrum vine.

Unripe berries are green, and ripe berries are red. Dried ripe berries yield white pepper, and despite the fantastic medieval legend propagated by Isidore of Seville (560–636) that the scorching of pepper crops blackened the berries and drove out the poisonous guard snakes, unripe pepper berries are simply plucked, gathered, cooked, and then dried to give us the most familiar variety, black pepper. The principal traders of pepper came from India where the vines thrived in tropical regions. Pepper was used in medicine to aid digestion and to treat ailments like gout and arthritis, as well as infectious diseases like the bubonic plague.

The term “peppercorn rent” derives from the practice established in early common law in England that payment of rent or tax might be made by a peppercorn, to avoid the bother of exchanging real currency. Usually no peppercorns were actually collected during these transactions, but the spice represented a hard asset, and the term is still in use today in legal parlance to describe a token amount of rent money paid in order to keep a title alive. In all seasons, spices and their increasingly globalized trade during the Middle Ages affected medieval economies, and brought social, culinary, and health benefits to Europe. To this day, the flavors and aromas of medieval markets spice up the long, cold winter months.

Sources

Paul Freedman, “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced Our World,” The YaleGlobal Online Blog, March 11, 2003, http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/spices-how-search-flavors-influenced-our-world.

Daniel Myers. “Cameline Sauce.” Medieval Cookery. Last modified July 13, 2006. http://medievalcookery.com/recipes/cameline.html.

Freedman, Paul. Out of the East: Spices and Medieval Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Translated by Anthea Bell. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Leah Hyslop, “Where do Christmas spices come from?” The Telegraph.co.uk (blog), December 22, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/grow-to-eat/where-do-christmas-spices-come-from/

O’Connell, John. The Book of Spice: From Anise to Zedoary. London: Profile Books, 2015.

As friends and colleagues around the world prepare to celebrate festivals of light, we at the Index wish you all a luminous holiday season and a peaceful, prosperous New Year.

The governing offices of medieval church and state – such as emperor, king, pope, archbishop, abbot, mayor, and so on – were often filled by election, in accordance with public and canon law. Often, election by a voting body facilitated the peaceful transference of power, even if such decisions also considered the privileges of birth and rank, as well as the requirements of the church.

Under canon law, medieval people were guaranteed certain human rights, including welfare rights, the right of certain classes to vote, and religious liberty (Helmholz 3). Canonists supported the free exercise of these rights, as they believed them to be supported by biblical tradition. Common law, or ius commune, upheld that a right order of government on earth was based in natural law and the upholding of these God-given rights. In effect, common law and canon law were seen as linked systems, to be enforced at the highest level to promote God’s plan for the world. Voting rights were recognized under both systems, so that secular elections evolved from the system put in place by medieval canonists for choosing offices within the church (Helmholz 6).

Medieval elections took place primarily in three contexts, ecclesiastical, secular and academic, but detailed evidence about them is scarce. Voting in both ecclesiastical and secular elections could follow one of four main procedures: overseen by an external authority with no direct interest in the election; by indirect election, in which electors named a proxy to select the officials; by lot; and by ballot (Uckelman and Uckelman 3). In contrast to most modern practice, electors had a limited choice, and the outcome of an election was always subject to the judgment of their superiors. Medieval law also ruled that all of the electors had to meet at the same time in the same place, whether or not the actual voting was done in secret. This was to mimic the meeting of the apostles at Pentecost and to wait for divine guidance before voting (Helmholz 8).

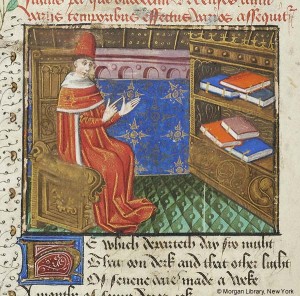

For some medieval rulers, the election, crowning, and anointing of Old Testament kings proved to be an excellent model for legitimizing their rule. Biblical tradition not only provided a justification for absolute reign, it also ensured that the church remained authoritative over secular rulers. In principle, the selection of a medieval monarch was based on both elective and hereditary elements, but from the tenth century in northern and central Europe, political and social trends steered toward hereditary succession over an elective monarchy (Nelson 183). This trend is exemplified in a French manuscript titled the Avis aus Roys, or royal advice book, dating to the mid-fourteenth century and possibly made for Louis, Duc d’Anjou (1339-1385). This book highlights the benefits of adhering to hereditary royal succession, which was widely seen as a more secure and manageable transference of power than other means of selecting a ruler.

The Church’s rules for filling ecclesiastical offices presented a paradox, as they strongly favored a mix of election and hierarchy. Before the papal bull In nomine Domini of 1059, which included an election decree, the pope’s successor was most often named by the incumbent pope or by secular rulers (Larson 151). Reforms put in place over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries resulted in the creation of the first papal conclave (1276) and College of Cardinals, the familiar process for electing the pope that is still in practice today. Below the pope were elected cardinals, archbishops, bishops, and other local offices for priests and deacons. Episodes of their ritual consecration, ordination, vesting, installation, and taking orders feature prominently in the Index subject headings. Another elective office common in the Middle Ages was that of abbot or abbess of a monastery.

Among the more numerous depictions of Benedict of Montecassino delivering rule to monks is a rare episode in an Italian manuscript depicting him chosen as abbot. In this Vita Benedicti, dating to the mid-fifteenth century, a miniature depicts a group of monks presenting a letter, stamped with a dangling wax seal, to the new abbot-elect standing in the doorway of his mountain monastery.

The Index collection includes many images of election-related imagery, including depictions of medieval leadership, kingly coronations, ecclesiastical consecrations, synods, and deliberating monks. Typical subject headings include David: proclaimed King, Solomon: crowned King; Simon Thassi: chosen Leader of Machabees; Edmund of England: Scene, Coronation and Consecration; Guillaume de Machaut, Livre du Voir Dit: Scene, King addressing Court; and Louis of Toulouse: Scene, taking of Orders.

Sources

Benson, Robert L. The Bishop-Elect: A Study in Medieval Ecclesiastical Office. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Barzel, Yoram, and Edgar Kiser. “The development and decline of medieval voting institutions: A comparison of England and France.” Economic Inquiry 35, no. 2 (1997): 244-60.

Uckelman, Sara L., and Joel Uckelman. “Strategy and manipulation in medieval elections.” Accessed in http://ccc.cs uni-duesseldorf. de/COMSOC2010/papers/logiccc-uckelman. pdf (2010), 1-12.

Helmholz, Richard H. “Fundamental Human Rights in Medieval Law.” (Fulton Lectures 2001): 1-18.

Nelson, Janet L. “Medieval Queenship.” In Women in Medieval Western European Culture, edited by Linda E. Mitchell, 179-208. New York and London: Routledge, 2011.

Weiler, Björn. “8 things you (probably) didn’t know about medieval elections.” History Extra Blog. N.p., 6 May 2015.

Larson, Atria. “Popes and Canon Law.” In A Companion to the Medieval Papacy: Growth of an Ideology and Institution, edited by Atria Larson and Keith Sisson, 135-37. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

Our website has had a lot of new traffic since its launch, and some users have reported difficulties getting into the database from our homepage. Please remember that if you normally access the database through an institutional subscription, you may still need to enter through your library website, using your institutional credentials. If you encounter other kinds of access problems, please use the staff contacts to let us know. We are happy to help.

Our website has had a lot of new traffic since its launch, and some users have reported difficulties getting into the database from our homepage. Please remember that if you normally access the database through an institutional subscription, you may still need to enter through your library website, using your institutional credentials. If you encounter other kinds of access problems, please use the staff contacts to let us know. We are happy to help.

The Index of Christian Art is pleased to invite applications for a one-year postdoctoral fellowship for AY 2017-2018, with the possibility of renewal contingent on satisfactory performance.

The Index of Christian Art is pleased to invite applications for a one-year postdoctoral fellowship for AY 2017-2018, with the possibility of renewal contingent on satisfactory performance.

Funded by a generous grant from the Kress Foundation, the Kress Postdoctoral Fellow will collaborate with permanent research and professional staff to develop taxonomic and research enhancements for the Index’s redesigned online application, which is set to launch in fall 2017. Salary is $60,000 plus benefits for a 12-month appointment, with a $2,500 allowance provided for scholarly travel and research. The Fellow will enjoy research privileges at Princeton Libraries as well as opportunities to participate in the scholarly life of the Index and the Department of Art & Archaeology.

The successful candidate will have a specialization in medieval art from any area or period; broad familiarity with medieval images and texts; a sound grasp of current trends in medieval studies scholarship; and a committed interest in the potential of digital resources to enrich work in art history and related fields. Strong foreign language and visual skills, the ability to work both independently and collaboratively after initial training, and a willingness to learn new technologies are highly desirable; previous experience in digital humanities, teaching, and/or library work is advantageous. Applicants must have completed all requirements for the PhD, including dissertation defense, before the start of the fellowship. Preference will be given to those whose subject expertise complements that of current Index staff.

Applications will be reviewed beginning January 15 and will continue until the position is filled. Applicants must apply on line at https://jobs.princeton.edu/applicants/jsp/shared/Welcome_css.jsp, submitting a C.V., a cover letter, a research statement, and the names and contact information of three references. The position is subject to the University’s background check policy.

Princeton University is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer, and all qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to age, race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, national origin, disability status, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law.

The Index is pleased to announce the speakers for two honorary sessions at the International Congress on Medieval Studies to be held at Western Michigan University (Kalamazoo, MI) on May 11-14, 2017.

Organized by Judith Golden and Jessica Savage, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Presider: Judith H. Oliver, Colgate University, Professor Emerita

This session will examine the interaction between words and images in medieval manuscripts as they shape the reader-viewer’s experience of the book. How do texts and images interact on the page? How did medieval readers respond to the varied discourses between images and texts? This session endeavors to open up new perspectives in describing, analyzing, and contextualizing manuscript illumination according to their intrinsic or peripheral textual elements. Papers in this session will undertake a close study of a particular manuscript and will expand upon theories for image-text composition by reviewing evidence of an artist’s written instructions; reading images with layered text additions, omissions or annotations; and recovering the reader’s experience through text and iconography.

“Artists and Autonomy: Written Instructions and Preliminary Drawings for the Illuminator in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea (HM 3027)”

“Bodies of Words: Text and Image in an Illustrated Anatomical Codex (Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 399)”

“A Votive ‘Closing’ in the Claricia Psalter (Walters MS W.26)”

Presider: M. Alison Stones, University of Pittsburgh, Professor Emerita

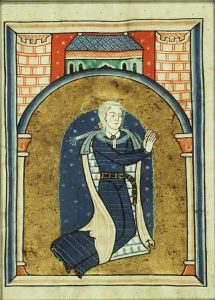

This session will examine the varied “visual signatures” of manuscript patrons, including dress, gestures, posture, and attributes of donor figures; heraldry and personalized inscriptions; marginal notes, colophons, dedications, and other signs of ownership and use in medieval manuscripts. Building on scholarship presented in the 2013 Index of Christian Art conference Patronage: Power and Agency in Medieval Art, this session will investigate the dynamic system of patronage centered on the interaction of owners with their books (whether as creator, patron, commissioner, or reader-viewer). Papers will address the importance of gender and social roles in book production, use, and readership, or will expand upon the role of patron as instigator in the book creation process, from payment to design.

“How Owner Portraits Work”

“The Patroness Portrait of the Fécamp Psalter (c. 1180): An Unknown Example of Royal Artistic Commission in Angevin Normandy”

“Patron Portrait as Creation Myth: On ‘Production Scenes’ in Illuminated Manuscripts”

In July 2016, Adelaide Bennett Hagens retired from the Index of Christian Art at Princeton University after fifty years of dedicated research and scholarship. She studied under Robert Branner at Columbia University and joined the Index during the directorship of Rosalie Green. Adelaide has studied medieval art in a variety of media, but her passion at the Index and in her personal research has always been manuscript illumination, particularly of the Gothic period. Her publications include “Some Perspectives on the Origins of Books of Hours in France in the Thirteenth Century,” in Books of Hours Reconsidered, edited by Sandra Hindman and James H. Marrow (2013); “Making Literate Lay Women Visible: Text and Image in French and Flemish Books of Hours, 1220–1320,” in Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces, edited by Elina Gertsman and Jill Stevenson (2012); and “The Windmill Psalter: The Historiated Letter E of Psalm One,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980). In two sessions, we celebrate Adelaide’s accomplishments and recognize her contributions to the Index of Christian Art and to the wider medieval and academic community.