As friends and colleagues around the world prepare to celebrate festivals of light, we at the Index wish you all a luminous holiday season and a peaceful, fulfilling New Year.

This year we’re inspired by the global interest in Index resources, which has grown considerably since we ended our yearly database subscription fees in 2023. Our last online database training session saw individual registrations from more than ten different countries, including Australia, Greece, Spain, Ireland, the UK, Italy, China, and Canada. Interchange with this wide network has been a highlight for us.

In 2024, we also offered online database tutorials, hosted classroom visits, and fielded more than one hundred research questions in person and online. Such interaction is at the core of the Index’s long history as a research tool and hub for scholarship in medieval art history. We here offer a selection of the highly varied questions asked of the Index in 2024:

Please continue to stay in touch. Follow us on Facebook and Bluesky; use our Research Inquiries form; and watch our blog for new events in 2025. Next year’s happenings include an online database training session, an Index Wintersession class on writing alternative text for images, the conference session “Breaking the Mirror” at the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, and a fall conference on “Art and Proof in the Ninth Century.” We look forward to sharing these events with you and to supporting your research for many years to come!

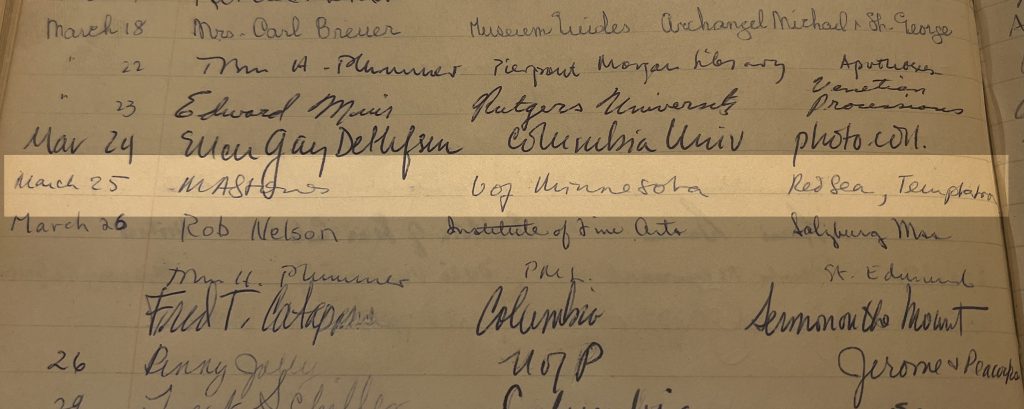

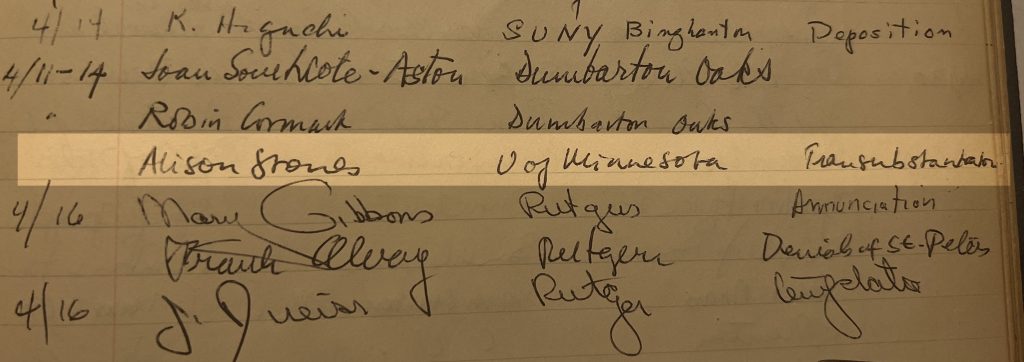

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank Alison Stones, Professor Emerita, University of Pittsburgh, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

In the Fall of 1969, I emerged as a not-quite Ph.D. from the Courtauld Institute (that happened a year later in December 1970/January 1971) to begin what would turn out to be a life-long academic career in the United States. My academic background was in French and German literature, followed by a medieval art and architecture specialty at the Courtauld where I worked with the inimitable Christopher Hohler, and with David Ross at Birkbeck, with musicology from Ian Bent at King’s and Heraldry with Nick Norman at the Wallace Collection.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

By 1969 I already had many friends in the US, notably Adelaide Bennett at the Index, Paula Gerson then at Fordham, James Marrow at Binghamton, and Bob Deshman at Toronto, Canada. All of them had worked alongside me in London, so the transition to the US was easy for me and all of them made me feel welcome there. The Index, under Rosalie Green, was among my first stopping places and continued over the years to be a haven for my research on French illuminated manuscripts, from the days of the invaluable old card system up to the new innovations of the 21st century. Adelaide and I would argue back and forth over the limitations and benefits of “Index-Speak” which invited us to hone our descriptive (and analytical) skills, and more recently it was a pleasure to encounter my former student Judith Golden among the ranks of the Index staff. One simply learned so much there!

Under Colum Hourihane came the era of the Index conferences, not-to-be missed sessions of innovative research, captured with regularity in the impressive series of publications produced under his editorship. I was privileged to attend many of these conferences and to participate in Iconography at the Index: Celebrating Eighty Years of the Index of Christian Art (1997),[1] Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus (2004),[2] as well as the festschrift volume Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer (2017).[3] Naturally, these essays all depended heavily on research conducted at the Index, where I must admit that my preference was still the old card system rather than the new, online version. Thankfully, the Index conferences are ongoing, and now available online with a livestream link. From the presentations to the interaction that follows, one learns so much!

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database over the last three decades? Where do you think Index work should go next?

As to future directions for the Index, I wish it could become a repository for the many online medieval databases (my own included) that risk becoming defunct once their creator retires. I appreciate the logistical issues and the problems of different software, but so much creative work is out there, and risks being lost. This in addition to the very valuable repository of information and images that make the Index such an indispensable tool for all medievalists. Long may it continue to flourish and many thanks for all I have learned there!

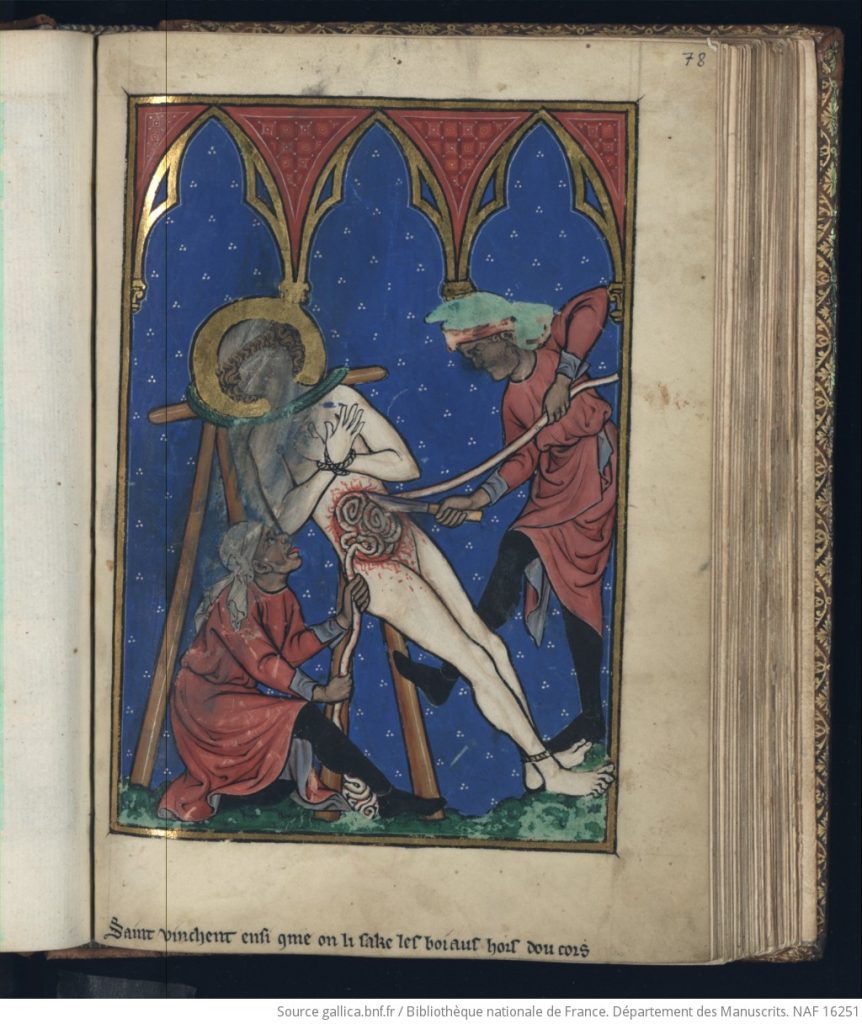

[1] Alison Stones, “Nipples, Entrails, Severed Heads and Skin; Devotional Images for Madame Marie,” in Image and Belief: Studies in Celebration of the Eightieth Anniversary of the Index of Christian Art, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 1999), 48–64.

[2] Alison Stones, “Questions of Style and Provenance in the Morgan Picture Bible,” in Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus: A Colloquium in Honor of John Plummer, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 2004), 112–121.

[3] Alison Stones, “Tobit: A Recently Rediscovered Cutting from the Brussels-Rylands Bible,” in Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer, eds. Pamela A. Patton and Judith K. Golden (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2017), 335–353.

Free registration is now open for on-site attendance at the Index conference “Unruly Iconography?” In it, eight speakers from a variety of fields will open new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules, challenging their listeners to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided when iconographic motifs should be considered canonical and which are instead “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” They will interrogate the value and limitations of the unspoken binaries that often underlie such labels: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, or center versus periphery. Their wide-ranging papers will demonstrate the value of a more critically aware, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

The conference will take place on November 9, 2024 in the Louis A. Simpson Building, A71, at Princeton University. Although the conference will not be recorded, a live stream link will provide digital access to those who cannot attend in person. Those planning to attend on site are asked to register to ensure adequate seating and refreshments.

Please find the full conference schedule and registration link here. We look forward to seeing you!

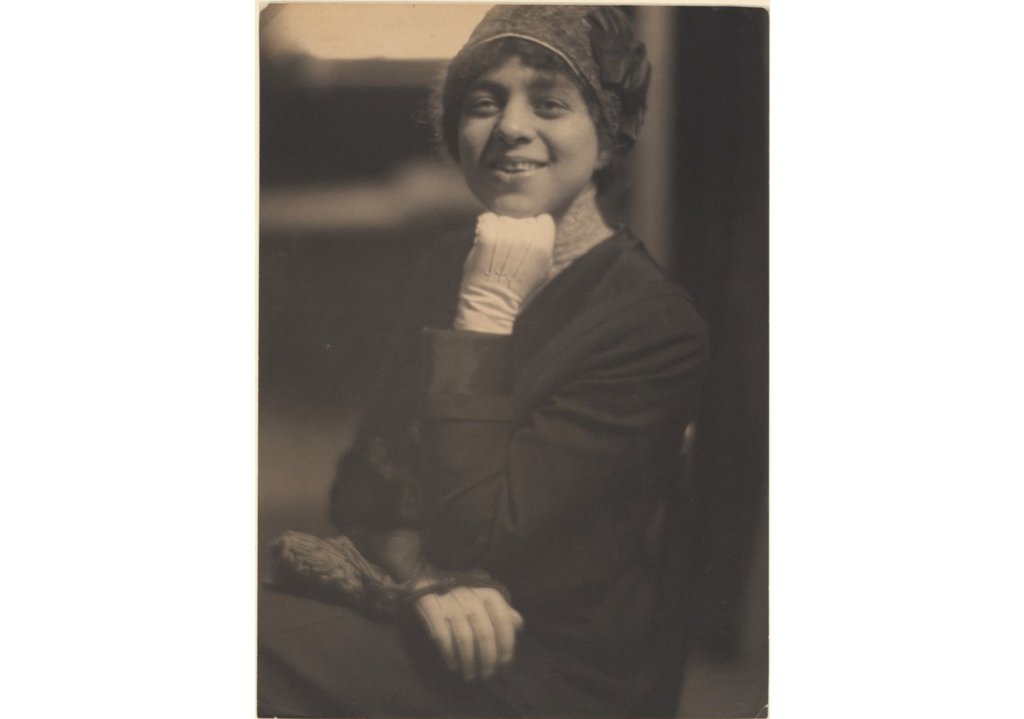

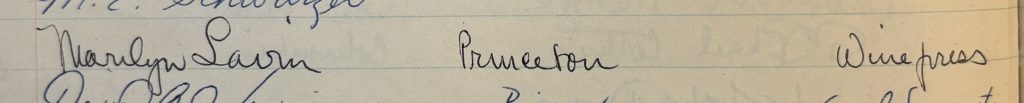

Many people know the name of Belle da Costa Greene, if not also her story as the fledgling librarian who rose to become librarian and then director of the famous Morgan Library & Museum in New York (1905–1948). A major exhibition opening this fall at the Morgan will explore the broad scope of Greene’s life and career, including the challenges she faced as a young woman of African-American heritage who lived as white in a field dominated by powerful European and American men. But where did Greene acquire the training in languages, history, and rare book studies that would advance her career? With the support of the Princeton Histories Fund, a team of researchers from Princeton University Library and the Index of Medieval Art set out to learn more. Their findings include the discovery of Greene’s hand in library records, a letter pinpointing the beginning of her work with the Morgan in summer 1905, and a fascinating correspondence documenting her continuing professional relationship with Princeton faculty and staff after her departure for New York.

These findings will be highlighted in a mini-exhibition opening on November 12, 2024 at Firestone Library and beginning with a round table discussing the project’s findings and their ramifications for Greene’s biography and the history of librarianship. Featured participants will include Kathleen Brennan of Princeton’s Mudd Library; Erica Ciallela of the Morgan Library & Museum and Schlesinger Library, Harvard University; and Mireille Djenno of Firestone Special Collections. The round table will be held at 4:30 pm on Nov. 12 in the Chancellor Green Rotunda, the very building in which the university’s library was housed during Greene’s time at Princeton. It will be followed by a reception and viewing in Firestone Library. Both round table and exhibition, supported by the Princeton Histories Fund, are free and open to the public.

The Index of Medieval Art is delighted to share a call for participation in a field seminar hosted by the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” at the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples on 12-13 June 2025. Associated with the conference “Unruly Iconography?”, which will be hosted on 9 November 2024 at the Index of Medieval Art, “Unruly Iconographies / Iconografie Indisciplinate” will take medieval Naples and southern Italy as a laboratory for exploring relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages.

The seminar organizers welcome proposals that consider individual case studies from medieval Naples and southern Italy as points of departure for investigating questions including so-called exceptions, hapaxes, mistakes, and lost originals; dynamics between “center” and “periphery”; challenges of chronology and dating in so-called peripheries and border zones; circulations of iconographies through polycentric cultural networks; translations of motifs across mediums, formats, functional contexts, and audiences; the legibility and illegibility of iconographies across cultures; mechanisms of transfer including mobile artworks, artists, and patrons; interplays between royal, non-royal elite, and non-elite patronage; and the limitations of previous models of iconography when confronted with cases in medieval Naples and southern Italy. They welcome in particular proposals that locate southern Italy within broader Mediterranean worlds, at the convergence of multiple cultural and religious currents including Latin and Orthodox Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

Further details and a compete call for papers are found here.

The Index of Medieval Art will sponsor the session “Breaking the Mirror: New Approaches to the Study of Medieval Images” at the 60th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo.

Everyone wants something from medieval images: a sense of story, a corroborated argument, a witness to medieval realities. Although the methods by which scholars seek these answers have evolved considerably, their work remains dominated by the conception of the medieval image as mirror, one that reflects either explicitly or indirectly the truths of the historical past. This session challenges this tendency by asking what we can really expect to learn from medieval images. How does their potential to go beyond illustration—to aspire, deceive, and even fantasize—complicate what and how scholars can learn from them?

We invite papers from researchers at all levels and especially encourage submissions from early-career scholars. The session’s hybrid format can accommodate up to two remote participants. Conference details and a full call for papers can be found at this link.

“Unruly Iconography?” opens a new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules. Its eight speakers will challenge their listeners to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided when iconographic motifs should be considered canonical and which are instead “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” They will interrogate the value and limitations of the unspoken binaries that often underlie such labels: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, or center versus periphery. Their wide-ranging papers will demonstrate the value of a more critically aware, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

“Unruly Iconographies?” will take place on November 9, 2024 and constitutes the first of two internationally linked conferences, the second of which will be a site-based seminar at the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” in Naples in June 2025, which makes southern Italy a laboratory for exploring the relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages.

Speakers for the conference are listed alphabetically below. A schedule and free registration link will be shared on this page in September 2024.

Diliana Angelova (UC Berkeley), “Lawless, Hilarious, Black: Eros and Companions in Byzantium.”

Alexander Brey (Wellesley College), “Iconography Between Empires: The Red Hall at Varakhsha.”

Heidi Gearhart (George Mason University), “A Poem, a Scribe, a Saint, and a Scriptorium: Evoking Multiple Presences in Arras Bibliothèque Municipale MS 860.”

Julie A. Harris (Independent Scholar, Chicago), “Indicate, Illustrate, Decorate, or Comment? Iberian Hebrew Bibles and Their Unruly Paratextual Marks.”

Krisztina Ilko (University of Cambridge), “The Chessmen of the Hunt.”

Nicole C. Paxton (John Cabot University), “Iconographic Innovation and Political Subversion in the Medieval Serbian Akathistos Cycle.”

Patricia Simons (University of Michigan/University of Melbourne), “The Goldfinch: Flights of Fancy.”

Mark H. Summers (University of Arkansas), “Dressed to Impress: Reconsidering Roger II of Sicily and the Iconography of Kingship.”

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to launch a new series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank our interviewees for their time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I’m not a medievalist but my work in Renaissance iconography has always depended on research material from earlier times. I had my first course in art history as a senior in high school, Mary Institute, St. Louis, 1942–1943. I majored art history at Washington University, St. Louis, receiving my M.A. (1949) under H.W. Janson, and did graduate work at the Institute of Fine Art, NYU, with Erwin Panofsky and others. I received my PhD on the basis of three related published articles in 1973.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located then? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

My first visit to the Index was in 1950. For a seminar with Panofsky, I was investigating the sudden appearance of the Infant St. John the Baptist in the Florentine early fifteenth century. The Index was in McCormick Hall. I met Rosalie B. Green and worked with her and Isa Ragusa. I also, by chance, met Professor Morey on that visit. I quickly found that the arrangement of the Index card catalog did not offer simple searching under the Baptist’s name. Learning the biblical structure of the index then helped me broaden the conceptual basis of my project and enriched my results.

In my years of working in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, it was always reassuring to know that the copy of the Index was there for consultation. In the 1980s, when I was a member of the Getty AHIP team, the precedence of the Index was a motivating factor in creating new computer tools for art historical research.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I am told that my article on the iconography of the Infant St. John, published in 1955 in The Art Bulletin remains useful up to the present day.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database? Where do you think Index work should go next?

With the appointment of Pamela Patton, the Index has finally hit its stride. Along with its change of name, broadened constituency, and superb technical improvements, the Index is fast becoming a major research center. It seems to me obvious that these advances indicate that the direction The Index of Medieval Art is going is the right one.

This blog post is the ninth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce our student worker Brooke Jurgenson.

What year are you in your Princeton education? What are some of your favorite courses or subjects?

I am a second-year student in the Class of 2026. I intend to declare psychology as my major, but I also love philosophy, literature, and art history. My first year, I really enjoyed the Western Humanities Sequence, which traced the development of the Western intellectual tradition through such foundational works as Augustine’s Confessions and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This semester, I am bridging my interests in psychology and philosophy with the course “The Psychological Foundations of the Mind” and branching out into linguistics by taking “On the Origins and Nature of the English Language.”

What do you do at the Index?

At the Index, I go through different iconographic categories, such as Virgin Mary, Dormition and Christ, Presentation, and add subjects to make the categories more comprehensive and accessible for researchers. For instance, I might add the subject tags “Joseph the Carpenter,” “Anna the Prophetess,” and “Dove” to all the records containing this imagery in scenes of the Presentation of Christ. I also collaborate with the Index research staff on refining the subject taxonomy and applying it more widely to records.

Aside from your experience at the Index, what was the most interesting job or internship you had?

In addition to fostering a love of medieval art at the Index, I have learned much about Princeton’s modern sculpture collection by serving as a Student Art Tour Guide with the Princeton University Art Museum. I lead small group tours around Princeton’s campus, highlighting the subtleties of Henry Moore’s bronze craftsmanship and Jacques Lipchitz’s mysterious abstractions.

What have you learned about medieval art since working for the Index? Has anything surprised you, or does anything stand out as extraordinary or curious about medieval art?

I absolutely love medieval art! Beautiful florals, ornate Latin scripts, gold pigments, and captivating renditions of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child regularly grace my screen. My appreciation for medieval art has grown immensely, and I have come to recognize just how rich and varied the subject area is.

I also never fail to come across the most mysterious and fun “hybrid creatures.” It is only here that I stumble across cats playing hurdy-gurdies and half-dragons slaying monsters. Medieval art truly expands your imagination.

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

This past summer, I took a somewhat impromptu trip to Berlin and visited the Bode Museum. I reveled in the amazing Byzantine collection there. Aside from medieval art, I enjoy Impressionism because of how it captures the ephemeral. My favorite work (as of right now) is Claude Monet’s “View of Vétheuil” painted in 1880, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Accession number 56.135.1).

What’s your favorite building or spot to sit on campus?

When it is warm outside, I love sitting on a bench in the garden behind Maclean House while reading. It is the perfect place to listen to the birds sing and feel the serenity of nature. I also love gazing at the stained glass windows of the Princeton University Chapel, watching the colorful dances of light play out in the sacred space.

Coffee or tea?

I avidly drink both coffee and tea, but I am a tea lover by heart. A steaming cup of freshly brewed green tea is all I need to be content.

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2024.

Although some scholars have claimed to see something like pizza in a wall painting at Pompeii, most historians trace the origins of modern pizza to sixteenth-century Naples. However, researchers at the Index of Medieval Art have discovered previously unrecognized medieval evidence of pizzerias in manuscripts dating at least two centuries earlier.

These early pizza-making scenes depict workers baking crusts, as in the miniature of a fifteenth century Book of Hours (Princeton University Library, MS Garrett 54). Notice how the pizza chef thrusts a long-handled peel with a round crust into a roofed pizza oven. Other steps in the preparation of crust have been identified in the iconography of pizzerias, including a hybrid figure tossing a circle of dough into the air to give the pizza its custom shape. Tossing dough in the air has long been the preferred method in pizza preparation to thin out the crust and give it its signature stretchy, glutinous finish.

Our research found that the toppings for pizza throughout the medieval period would have run the gamut. The typical meats and vegetables that popularly eaten today would have featured on pizza in the Middle Ages, too…with one major exception: the edible berry of the plant Solanum lycopersicum, more correctly identified as the Amoris pomum and commonly called the “the tomato.” Tomato sauce on pizza was strictly prohibited due to the prevalence of the belief that the love apple is the devil’s fruit. But pizza was always a highly customizable dish, and pizza mongers were apt to use any combination of sauces with any number of toppings to suit their palates. Pineapple and anchovies on pesto with casu martzu was a particular favorite among both penitents and unrepentant heretics alike.

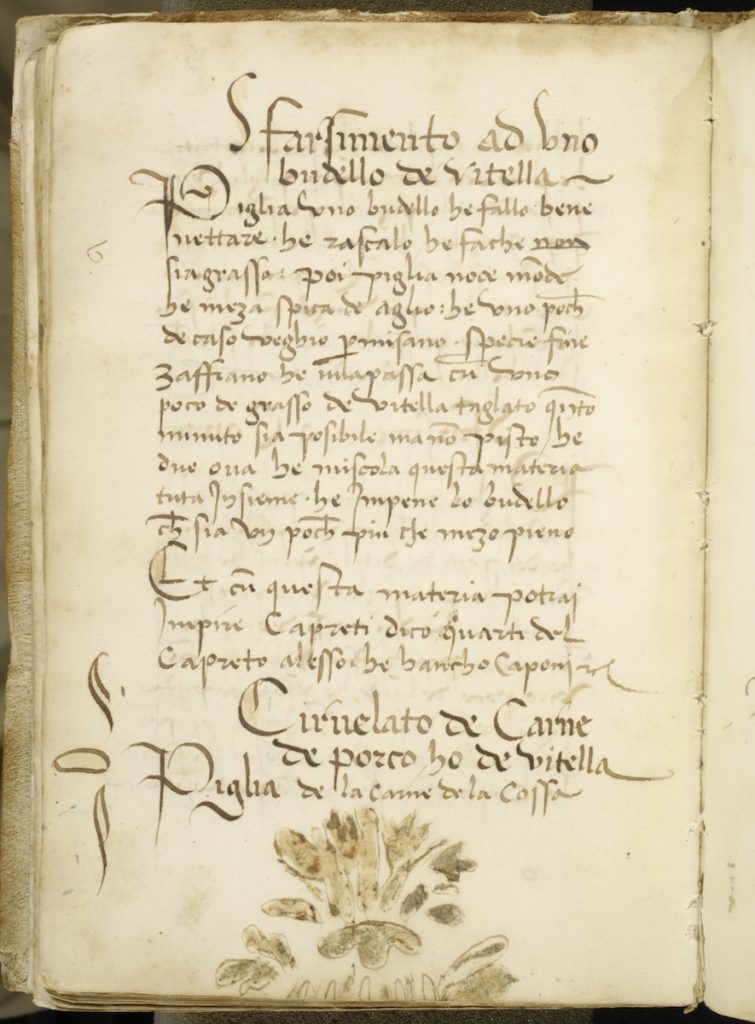

You can imagine our surprise at finding in one late fifteenth-century Neapolitan cookbook, known as the “Cuoco Napoletano,” a recipe for a type of blood sausage known as cervellato (manuscript inscribed “Cirvelato de carne de porco ho di vitelli”) with a mention of its use in pizza preparation. Legendarily, and much like today, sausage was a favorite topping among medieval consumers of pizza, and the following leaf in the cookbook describes such usage in great detail. Or are you a fan of fungi on your pies? Mushrooms too made it onto the menus of pizza chefs, and some illustrations in medieval manuscripts show the fleshy morsels lined up and ready to chop.

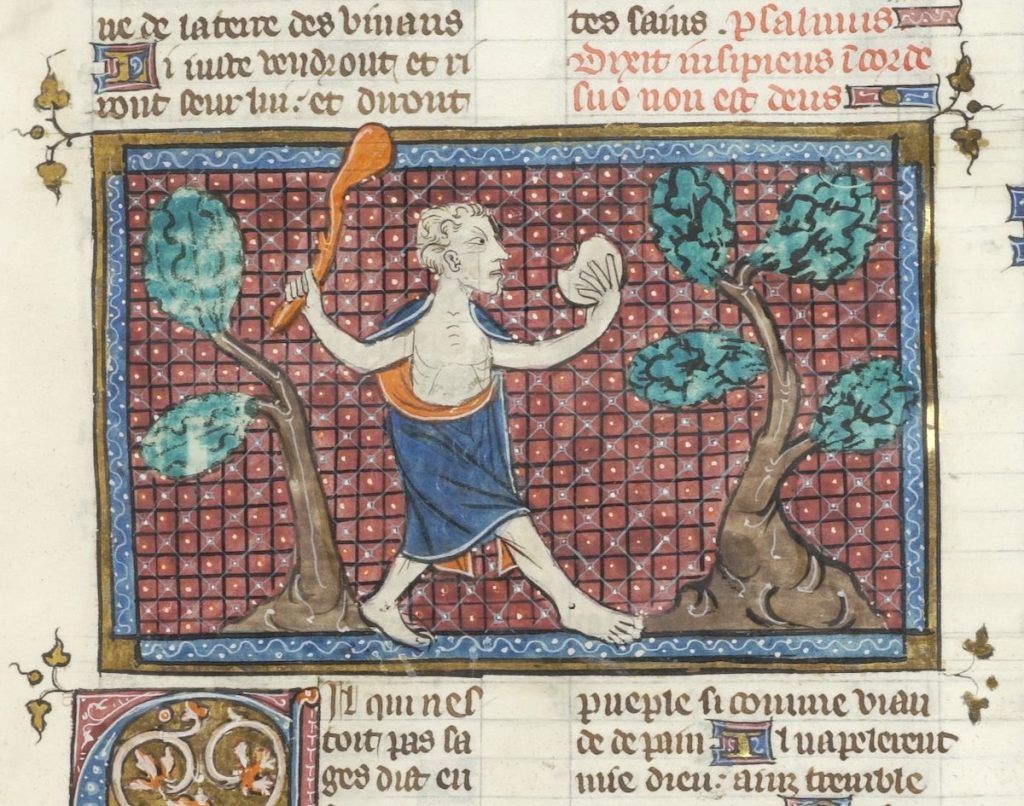

Whether deep-dish or thin with extra cheese, pizza was prized in the Middle Ages. Pizza to go wasn’t out of the ordinary, either, but the pie would have to be fiercely guarded by its consumer. Eating a slice, or “wolfing ’za” as the medieval collegiate vernacular would have it, was often a perilous, two-handed operation. In one medieval image, you’ll notice that a large man chowing down on a delicious slice folded in one hand was required to wield a club with his free hand to ward off would-be pizza poachers!

It was also a seasonal favorite. Such early forms of a pizza would have been regarded as the perfect addition to any menu on the first day of April.

(And by the way, April Fool!)