Please join the Index of Medieval Art for a one-day conference that examines the role of the visual in the negotiation of medieval power relationships, whether political, social, religious, or individual. Eight scholars with a range of specializations will address how works of medieval art were used to impose and maintain power over others, to resist dominant figures or regimes, or as agents in the back-and-forth of an ongoing power struggle. Speakers will include:

Heather Badamo, University of California, Santa Barbara

Elena Boeck, DePaul University

Thomas E.A. Dale, University of Wisconsin

Martha Easton, St. Joseph’s University

Eliza Garrison, Middlebury College

Anne D. Hedeman, University of Kansas

Tom Nickson, Courtauld Institute of Art

Avinoam Shalem, Columbia University

106 McCormick Hall, Princeton University

Organized by Elina Gertsman and Vincent Debiais and hosted at the Index of Medieval Art

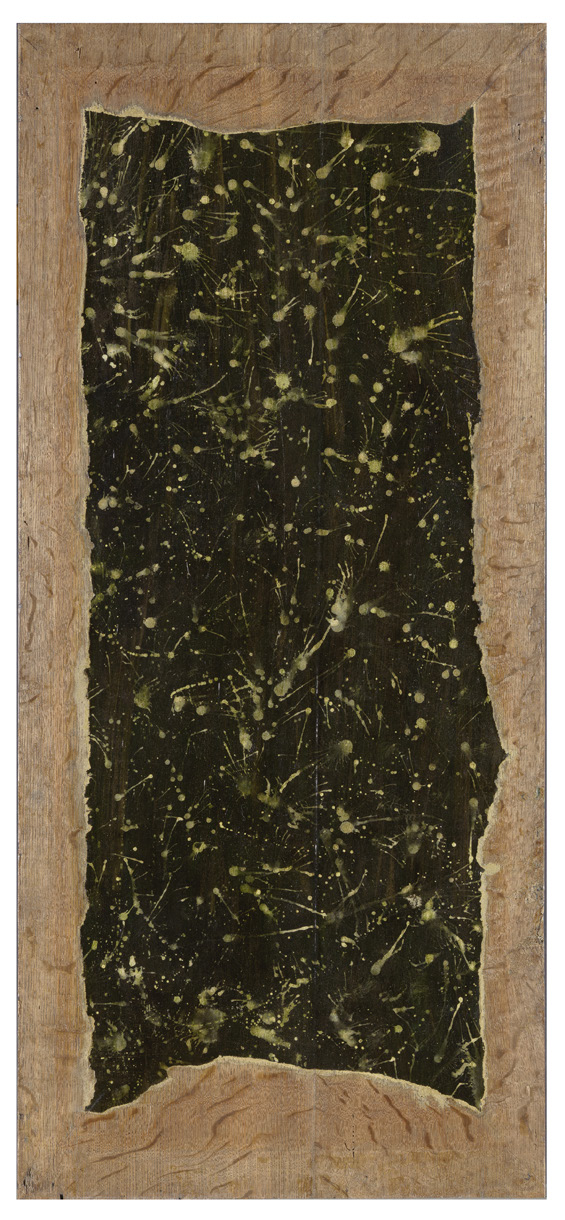

Focusing on the long and rich tradition of nonfigurative art, this international symposium will explore the inception and transformation of abstraction(s) at various historical pivot points between the advent of Christianity and the interrogation of epistemological queries in the later Middle Ages. The symposium aims to introduce the concept of abstraction to the field of premodern art and redefine it as a visual structure that predicates the very nature of image-making. We seek to interrogate non-figurative forms in medieval material culture; to contextualize these forms within the contemporaneous cultural and philosophical discourses; to identify the common features that favor the emergence of abstraction specifically in the long Middle Ages; and to determine how abstraction has been used to make visible what is beyond any kind of representation. For the full schedule, click here.

Registration is free but required to guarantee seating.

The conference is co-sponsored by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the French-American Cultural Exchange Foundation, the Index of Medieval Art, Case Western Reserve University, and the École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

Eclecticism at the Edges: Medieval Art and Architecture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Cultural Spheres c.1300–c.1550

On April 5-6, 2019, the Index will co-host “Eclecticism at the Edges: Medieval Art and Architecture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Cultural Spheres,” along with the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, the Department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University, The Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Stanley J. Seeger Hellenic Fund, the Mary Jaharis Center for Byzantine Art and Culture, the International Center of Medieval Art, and the Society of Historians of East European, Eurasian, and Russian Art and Architecture. This two-day symposium focuses on the art, history, and culture of Eastern Europe between the 14th and the 16th centuries .

In response to the global turn in art history and medieval studies, “Eclecticism at the Edges” explores the temporal and geographic parameters of the study of medieval art, seeking to challenge the ways in which we think about the artistic production of Eastern Europe from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries. This event will serve as a long-awaited platform to examine, discuss, and focus on the eclectic visual cultures of the Balkan Peninsula and the Carpathian Mountains, the specificities, but also the shared cultural heritage of these regions. It will raise issues of cultural contact, transmission, and appropriation of western medieval and Byzantine artistic and cultural traditions in eastern European centers, and consider how this heritage was deployed to shape notions of identity and visual rhetoric in these regions that formed a cultural landscape beyond medieval, Byzantine, and modern borders.

You can view the program here.

The symposium is free, but registration is required to guarantee seating. For any queries, please contact the organizers at eclecticism.symposium@gmail.com.

NB: This satirical post was shared in celebration of April Fool’s Day 2019.

From time to time, we Indexers like to lift the veil, so to speak, on the cataloguing procedures and upgrades that we have undertaken online. One of our current priorities is filling out our Subject Authority records. These records are where researchers can find further information about a given iconographic subject, including the preferred term used by the Index for that subject and a brief description of the iconography, its main attributes, and its relevant cultural details.

We know that visitors to the database may use alternate names, spellings, or related terms for a particular subject during a search query, and we’re determined to help you find them. As we Indexers like to joke, one scholar’s Maiestas Domini is another scholar’s Christ in Majesty! (rim shot) It is for this reason that we supply a field for “See-From” terms, a list of alternate names and phrases that will redirect you to the preferred Index iconographic term.

Below is a sampling of our newest subject authority terms offered as an overview of our work methods, as well as a sense of where our field is heading with regard to iconography.

NAME: COCONUT

Note: Aural method of riding in medieval Britain that consisted of banging two empty halves of coconuts together to mimic the sound of horse hooves. Nota bene: the coconut is not indigenous to the region and likely arrived due to the migratory practices of the African Swallow.

See-Froms:

NAME: FRENCH PERSONS

Note: Surly Gallic individuals speaking with outrageous accents and serving Guy de Loimbard, possessor of “a” Holy Grail. Experts in deploying taunts at their enemies.

See-Froms:

NAME: LIVESTOCK (ARMS AND ARMOR)

Note: Favored weaponry of French Persons, comprising cows, geese, and other assorted farm animals to be hurled over castle walls.

See-Froms:

NAME: KNIGHTS WHO SAY “NI!”

Note: Darkly-clad knights wearing helmets bearing cow horns, keepers of the sacred words “Ni,” “Peng,” and “Neee-Wom.” Those who hear them seldom live to tell the tale. Lovers of ornamental garden elements that are nice and not too expensive.

See-Froms:

NAME: RABBIT OF CAERBANNOG

Note: A deceptively cuddly rabbit who is a foul, cruel, and bad-tempered thing. It guards the entrance to the Cave of Caerbannog, home to the Legendary Black Beast of Arrrghhh.

See-Froms:

NAME: HOLY HAND GRENADE OF ANTIOCH

Note: One of the sacred relics created to “blow thine enemies into tiny bits.” Instructions for its use found in the Book of Armaments 2:9–21.

See-Froms:

NAME: CASTLE ANTHRAX

Note: Castle with admittedly not a good name but possessing beds that are warm and soft and very, very big. It houses eightscore young blondes, cut off from the rest of the world with no one to protect them. These females enjoy bathing, dressing, [SCENE, OBSCAENA], making exciting underwear, [SCENE, OBSCAENA], and after [SCENE, OBSCAENA], [SCENE, OBSCAENA]. *

See-Froms:

* Note from the Editors: Given our reputation as a family-friendly blog, we have decided to redact this particular authority record. To that end, we have dusted off the Index’s trusty early twentieth-century subject heading “Scene, Obscaena.” As you readers are well aware, Latin makes everything sound more modest. The cataloguer responsible has been sacked.

Angels often function as messengers of God in the Bible. Perhaps the best-known example of this is Gabriel’s role in the Annunciation, a subject catalogued over two thousand times in the Index. He is identified by name in Luke 1:19, which describes him as saying “I am Gabriel, who stands before God…” as he brings word to the Virgin Mary that she will bear the son of God.

The story of the Annunciation and Gabriel’s part in it appears in the gospel of Luke 1:26–38. It recounts how God sent Gabriel to Nazareth to the home of the Virgin Mary. There, the archangel announced “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with you: blessed are you among women” (Ave gratia plena; Dominus tecum; benedicta tu in mulieribus) found in verse 28. The reason for this greeting appears a few lines later in verse 31: “…for you have found grace with God. Behold you shall conceive in your womb, and shall bring forth a son….” In verse 35 Mary, as yet unmarried, learns how this will come about: “The Holy Ghost shall come upon you, and the power of the Most High shall overshadow you.”

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Annunciation was depicted with varying degrees of complexity, and the means by which Gabriel brings his news varies as well. On the central portal of the Reims cathedral west façade (1245–1255), two statues of Gabriel and Mary stand next to each other, Gabriel smiling happily, Mary pensive. Here Gabriel offers nothing beyond a cheery expression, and very probably a gesture of blessing with his now-missing right hand. Yet the story was familiar enough that the two principals in close proximity would have triggered the memory of the Annunciation story for the viewer.

In the slightly more elaborate scene from a sixteenth-century Gradual in Princeton University Library (Princeton 11, fol. 2r), Gabriel approaches from the left, with his right hand holding a scepter, a reference to kingship, and with his left hand indicating the dove of the Holy Spirit hovering above Mary’s head. No words are exchanged. Gabriel’s verbal message is implied by his symbolic scepter and gesture.

Gabriel’s message is more overt in a highly detailed Annunciation image in an elegant fifteenth-century Book of Hours in the Morgan Library (M.893, fol.12r). The Trinity is present—God appears in a foliate medallion at the upper left, generating rays on which a mini Christ Child, carrying a wooden tau cross, glides downward. At the end of the rays, the Holy Spirit, again in the form of a dove, approaches Mary’s head. She observes this scene with some trepidation, raising her left hand as if to stop all this activity. At left, Gabriel holds a scroll inscribed Ave gratia plena dominus tecum benedicta tu in meenlieribus (sic). Mary is kneeling at a draped prie-dieu, her right hand resting on an open book lying on a pillow, emphasizing her piety, while at right in a niche is a vase with a stem of lilies evoking her purity. The plethora of symbolic forms suggest that the message is being fulfilled at the same time as Gabriel is delivering it, even as Mary’s raised hand says “I am not worthy.”

Gabriel bears his message in an unusual and possibly unique way in the Morgan Library copy of the Concordantiae caritatis (M.1045, fol. 7v). The text of this manuscript was originally written by Ulrich von Lilienfeld, a Cistercian monk in Lilienfeld, Austria, sometime between 1351 and his death in 1358. It is a typological text relating saints’ lives, Old and New Testament topics, and moralizing texts about nature. The manuscript provides sermon material, and is arranged in the order of the church year. The Morgan copy was written and illuminated in Austria in the third quarter of the fifteenth century.

In the Concordantiae Annunciation, the Virgin Mary appears to be kneeling, holding an open book with both hands. A dove descends toward her head as she looks back over her left shoulder. Her gaze is directed toward Gabriel, who kneels, both hands extending a partly folded document bearing three columns of pseudo-writing and three seals hanging from its lower edge. Why is Gabriel shown with this very unusual attribute?

The answer may lie in the special format of Gabriel’s document, which resembles that of legal documents in the Middle Ages. The agreement was written on the page itself, while seals appended to the bottom served as the signatures of the parties involved in the contract. The number of seals depended on the number of individuals taking part. Since three seals appear here, it is not a great leap to imagine them representing the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Is Gabriel delivering a signed contract to Mary, with the particulars outlined in three columns above the seals? Exceeding the traditional verbal greeting with which he communicates that Mary will become the mother of God, Gabriel here delivers a hard copy of a binding compact, leaving her no option but to accept.

Judith K. Golden, Art History Specialist

When the Index of Medieval Art launched its new online database application in 2017, we were excited that its modernized, user-friendly design would make our data more accessible to both experienced and neophyte researchers. We hoped also that moving to a proprietary, cloud-based design would lower operating costs, making the Index more financially accessible as well. And indeed it did: in our first year, we were able provisionally to lower institutional and individual subscription fees by one third and have seen subscription numbers rise as a result.

We’re now delighted to announce that as of July 1, 2019, we’ll be able not just to let the new rates stand, but to lower both subscription fees further by another $100, setting institutional fees at $850 and individual fees at $250 per annum. We hope that this further reduction, while modest, helps to bring the resources of the Index within reach for more researchers at a time of increased financial pressure on humanities scholars globally.

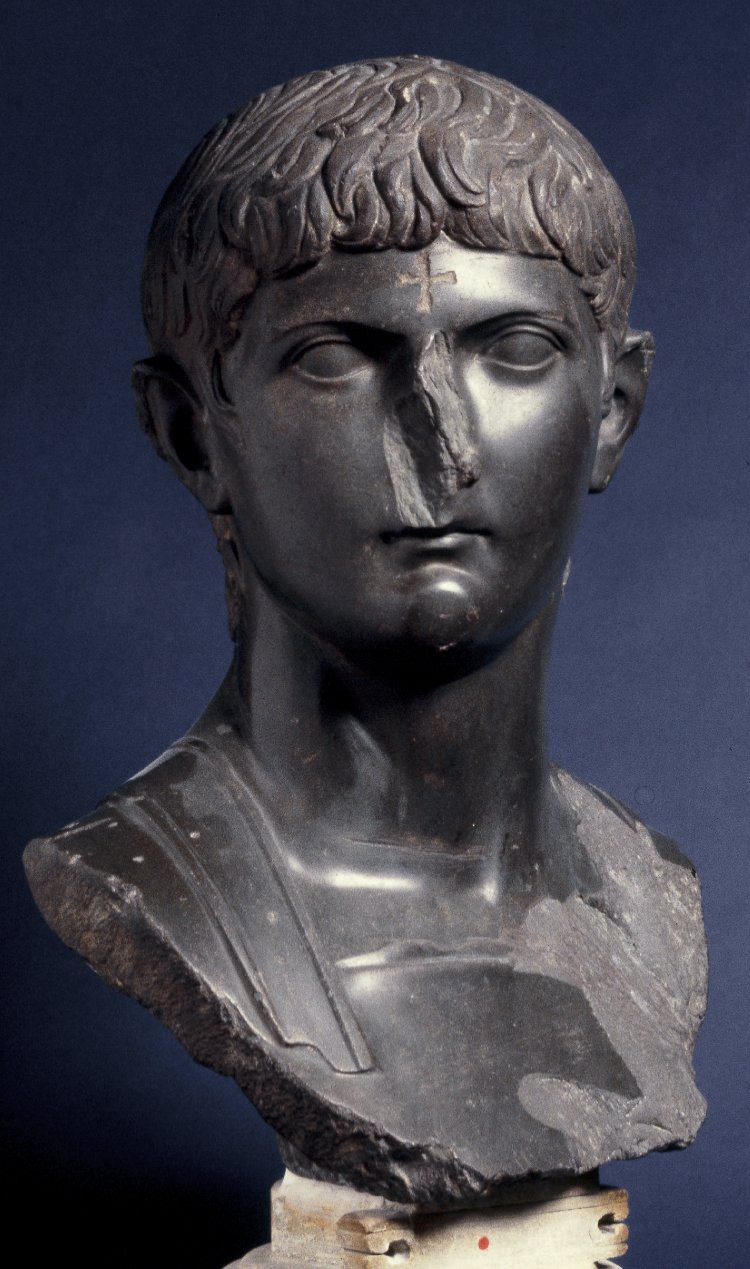

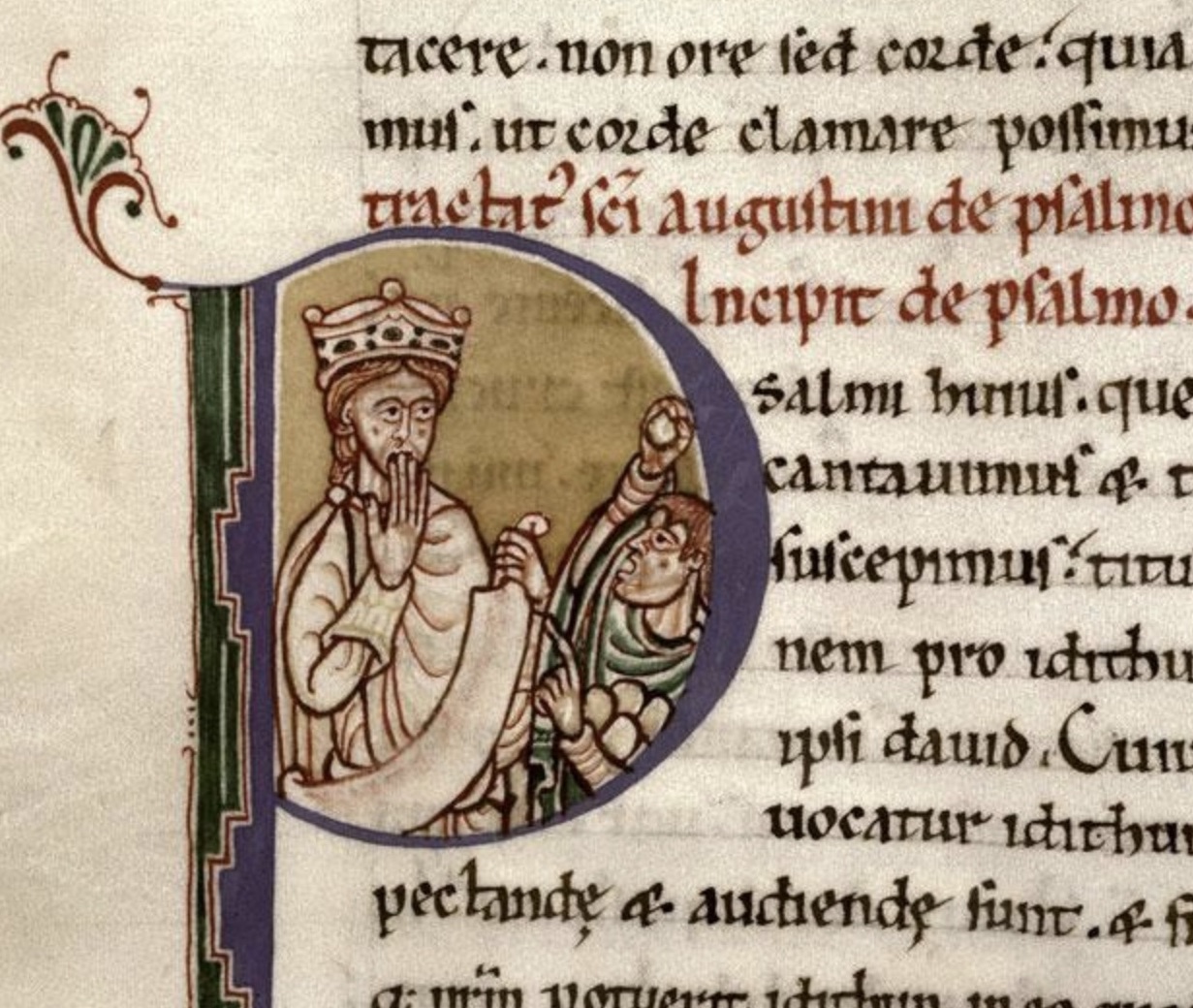

King David is well represented in the Index of Medieval Art database, with close to 200 subject headings covering the various scenes of his life. He is most often depicted as a richly garmented king, often with his role as the psalmist suggested by his signature harp and crown. One variant of his iconography, which I encountered while cataloguing a historiated initial from an early sixteenth-century French Psalter, presents a familiar subject in the life of David, described by the Index as David, Communicating with God (Fig. 1). However, in this example, the kneeling David adds an extra gesture to his prayer routine. Where one would expect to find reverent folded hands, David emphatically points his finger to his protruding tongue!

While studying this initial, I decided to use the tools in the updated Index database to explore how David’s pose and the purposeful indication of his tongue were related to the psalm verse. In this Psalter, the initial D for Dixi begins Vulgate Psalm 38, verse 2: Dixi custodiam vias meas; locutus sum in lingua mea posuri ori meo custodiam cum consisteret peccator adversum me… (Douay-Rheims Bible, accessed 22 February 2019, http://drbo.org/). Translated, this reads “I will take heed to my ways, that I sin not with my tongue. I have set guard to my mouth, when the sinner stood against me.” The tongue is mentioned one more time in this psalm at verse 5 with regard to speech, “I spoke with my tongue: O Lord, make me know my end. And what is the number of my days: that I may know what is wanting of me” (drbo.org). The image of David thus prefigures the textual passages of the psalm in that both image and text suggest the speaking and offending capabilities of the tongue. But, how often do we see David depicted with his tongue sticking out? And can we find other contexts for his expressive gesture?

I entered a simple keyword search for “tongue” in the upper right search bar on the Index database homepage and used the Subject Filter to refine my results to David, Communicating with God. Immediately, I located a much earlier scene from a Parisian Bible in the Morgan Library dated to the first quarter of the thirteenth century (Fig. 2). This initial D, also beginning Psalm 38, encloses a beardless, crowned David, looking up toward the face of God and mirroring the action of raised finger to outstretched tongue.

Since both of these images open Psalm 38, the presence of magnified tongues seems intended to show that significant body part that David was obliged to “sin not” with.

This connotation of the image is better understood in the context of the medieval preoccupation with the peccata linguae, or “sins of the tongue,” such as those assigned to fallen characters in the Divine Comedy and the Roman de la Rose. These transgressions of speech include flattery, duplicity, evil counsel, discord, and blasphemy. Medieval moralists also were concerned with sinful tongues: the Franciscan John of Wales (d. 1285), for example, wrote a preaching treatise called De Lingua (“The Tongue”), which outlined the proper duties of a “good” tongue as to share in ethical knowledge and to oppose its own natural “bad” inclinations.

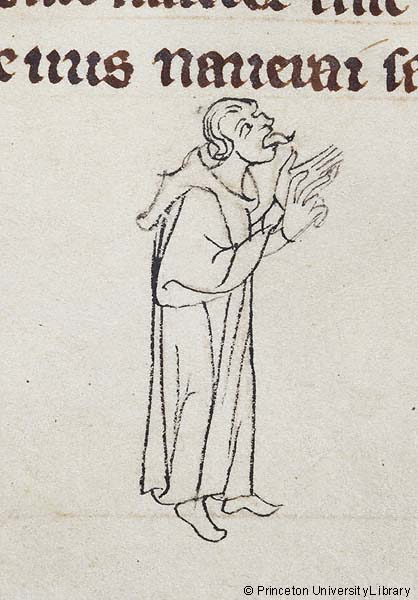

In medieval art, depictions of sinful tongues like David’s can be found in figural representations of Slander, False Seeming, and other personifications of vice. A figure identified as the Unmerciful Judge sticks out his tongue in the lower margin of a 15th century Manuel des Péchés to illustrate the Exemplum, or lesson, for the Sins of Avarice and Covetousness (Fig. 3). His long, curled tongue and raised hands suggest how insistently he imparts this lesson on the vices. However, his prominent tongue is also inherently tied to his cruel speech, offering a visual metaphor of merciless judgment.

Wishing to investigate further the iconography associated with Psalm 38, I used the Index database to browse through the numbered psalms in the Subject Browse List. Clicking the subject heading for Psalm 039 (Vulg., 038) revealed that a majority of the illustrations depict David pointing to his mouth, a common way to represent speech, but without his tongue sticking out. One such initial appears in the Noyon Psalter, attributed to the Master of the Ingeborg Psalter, in the J. Paul Getty Museum (MS. 66, fol. 41v). This suggests that the literal representations of David’s tongue were the more unusual depiction. To take this theory a step further, I repeated the keyword search for “mouth” and refined the subject to David, Communicating with God. This search yielded about 30 examples where David was indicating his closed mouth, a subject that is particularly common in manuscript initials associated with Psalm 38.

Medieval commentaries on Psalm 38 help to explain the popularity of this iconography. Theodoret’s Commentary on Psalm 38 notes the text’s emphasis on the sinfulness and “lowliness” of human nature and humanity’s need for deliverance, while Augustine wrote of the same psalm that, although the tongue was “prone to slip,” bridling it will help one stand against wicked enemies. Both commentators connected Psalm 38 to an episode in Samuel, where David was viciously pursued by Absalom and abused by Shimei, who threw sticks and stones at him while he fled from Jerusalem. That biblical narrative itself is sometimes found illustrating Psalm 38 (see the related Index subject heading David, Cursed by Shimei). In a manuscript of the Enarrationes in Psalmos, dating to the mid twelfth century, a historiated initial P encloses a crowned David covering his mouth while Shimei hurls stones at him (Fig. 4). Here, David’s cautious gesture and muted tongue show his restraint from sin, shedding light on the meaning of the gesture when it appears in the psalm initials.

Finally, I decided to broaden my search to locate all depictions of this particular body part with David. I repeated the keyword search for “tongue” and set the Subject Filter to David. This led me to a historiated initial in the twelfth century English manuscript of the Saint Albans Psalter and to another layer of iconographic context. Here, the initial E for Erucatavit, beginning Vulgate Psalm 44, encloses a seated and crowned David, who raises a pen in his right hand and with his left index finger points to his extended tongue (Fig. 5). Written in red ink above the incipit is the rubric Lingua me calamus scribae, taken from verse 2 of that Psalm, which can be translated as, “My tongue is the pen of a scrivener”(drbo.org). This verse of Psalm 44 is preceded by the mention of David’s verbum bonum, or the “good word” uttered from his heart to the king (mea regi), suggesting that goodness issues from him and through him, by way of tongue and pen.

With regard to this Vulgate Psalm 44, Augustine comments,

What likeness, my brethren, what likeness, I ask, has the “tongue” of God with a transcriber’s pen? What resemblance has “the rock” to Christ? (1 Corinthians 10:4) What likeness does the “lamb” bear to our Saviour (John 1:29), or what “the lion” to the strength of the Only-Begotten? (Revelation 5:5)

(Augustine, Expositions, Digital Psalms version, p. 264)

Today, we enjoy ample use of emojis, which add expressive meaning to our messages to one another. In the Middle Ages, manuscript illuminators did not miss the opportunity to illustrate textual passages with similarly expressive visual cues in images, which also linked to the complex layers of meaning readers anticipated finding in the psalms. Although David’s gesture to his closed mouth seems to be a relatively common composition, the emphasis on his stuck-out tongue in certain depictions speaks just as expressively of its sinful capabilities as it does of its usefulness as an obedient tool.

The investigation of David’s “emoji” highlights how researchers can look for specific iconographic motifs in the Index by combining keyword searches in the description field and filtering with controlled headings in Advanced Search options. For advice on your own research topic and forming search strategies using the Index database, send us a Research Inquiry. We’ll be 🙂 to hear from you!

Sources

Baika, Gabriella I. “Lingua Indiciplinata: A Study of Transgressive Speech in the ‘Romance of the Rose’ and the ‘Divine Comedy.’” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2007.

Craun, Edwin D. Lies, Slander, and Obscenity in Medieval English Literature: Pastoral Rhetoric and the Deviant Speaker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. See especially pp. 33–34.

Douay-Rheims Bible. Accessed 22 February 2019. http://drbo.org/.

Gellrich, Jesse M. “The Art of the Tongue: Illuminating Speech and Writing in Later Medieval Manuscripts.” In Virtue & Vice: The Personifications in the Index of Christian Art, 93–119. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. See especially pp. 108–109.

Hill, Robert C. “Commentary on Psalm 39.” In Commentary on the Psalms, Psalms 1–72, 233–36. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2000. St. Aurelius Augustine. Expositions on the Psalms, Digital Psalms version 2007, 205–216, 262–277. Accessed 22 February 2019. https://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/otesources/19-psalms/text/books/augustine-psalms/augustine-psalms.pdf. See especially pp. 205–206, 264–265.

Going to Kalamazoo this year? Ever wanted to learn more about the impact of digital tools and methods on medieval art research? Be sure to circle your programs for two exciting sessions on current topics in iconography, a roundtable and a workshop, co-organized by Maria Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage of the Index of Medieval Art.

I. Saturday, May 11 at 10:30am [Session 346]

Encountering Medieval Iconography in the Twenty-First Century: Scholarship, Social Media, and Digital Methods (A Roundtable)

Stemming from the launch of the new database and enhancements of search technology and social media at the Index of Medieval Art, this roundtable addresses the many ways we encounter and access medieval iconography in the 21st century. Our five participants will speak on topics relevant to their area of specialization and participate in a discussion on how they use online resources, such as image databases, to incorporate the study of medieval iconography into their teaching, research, and public outreach.

Digital Information and Interoperability: Facing New Challenges with Mandragore, the Iconographic Database of the BnF

Sabine Maffre, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Ontology and Iconography: Defining a New Thesaurus of the OMCI at the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, Paris

Isabelle Marchesin, Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA)

Iconography at the Missouri Crossroads: Teaching the Art of the Middle Ages in Middle America

Anne Rudloff Stanton, Univ. of Missouri

Medieval Iconography in the Digital Space: Standardization and Delimitation

Konstantina Karterouli, Dumbarton Oaks

Online Resources in the Changing Paradigm of Medieval Studies

Marina Vicelja, Center for Iconographic Studies, Univ. of Rijeka

II. Sunday, May 12 at 8:30am [Session 505]

Lost in Iconography? Exploring the New Database of the Index of Medieval Art (A Workshop)

This workshop will demonstrate how to get the most out of the new Index of Medieval Art database by using advanced search options, filters, and browse tools to research iconographic subjects. A short presentation will introduce the new subject taxonomy search tool that will further facilitate exploration of the online collection.

We look forward to an invigorating discussion on current issues in iconographic research and to sharing an update on the new database. You can find out more about the 54th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, held from 9-12 May 2019, including the full schedule here.

The Index is happy to host the scholarly conference “Abstraction before the Age of Abstract Art,” organized by Profs. Elina Gertsman (Case Western Reserve University) and Vincent Debiais (École des hautes études en sciences sociales) with the generous support of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the French-American Cultural Exchange Foundation, Case Western Reserve University, and the École des hautes études en sciences sociales. The conference will be held on May 18, 2019; speakers include Jean-Claude Bonne,

Licia Buttà, Vincent Debiais, Thomas Golsenne, Herbert Kessler,

Robert Mills, and Cécile Voyer.

A full schedule and free registration form will be available after April 7 at https://ima.princeton.edu/conferences.

“We three kings of Orient are…” runs the traditional Christmas carol. If you were that kid who wondered “Just who are these guys with their weird-sounding gifts? And where’s ‘Orientare’ anyway?” this blog post is for you.

The story of the Magi originated in the Gospel of Matthew (2:1-12), which tells of “wise men from the east” (magi ab oriente) who traveled to Jerusalem seeking the king of the Jews after seeing a star portending his birth. When they reached Bethlehem, Matthew recounts, they fell and adored him, offering gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Although this fairly skeletal story offers few details about how the magi looked or from where “in the east” they hailed, that didn’t stop medieval artists from developing their Biblical story into an elaborate visual tradition.

Matthew offers no information about the number of magi who made the trip to Bethlehem. The tradition of depicting them as a trio predominated from the third century onward, perhaps inspired by the three gifts mentioned in the biblical account. Nonetheless, early medieval depictions of the magi in other numbers, such as two, four, or even six, can occasionally be found. Matthew also remains silent about the magi’s names; the ones with which we are familiar today—Melchior, Caspar, and Balthazar—appear much later, in Byzantine texts and images of the sixth century. One of the earliest such instances is the Adoration of the Magi mosaic in Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, where the elder, foremost magus is labeled Caspar, rather than Melchior, as more often would be the case in later medieval art.

Despite the lack of information about the locations from which the magi came, artists quickly developed ways of visually emphasizing their foreign origins. Early medieval images drew on traditional Roman representations of non-Roman peoples paying homage to the emperor, depicting the magi in appropriately “outlandish” dress such as the short tunics, brightly patterned leggings, and forward-peaked Phrygian caps that appear at Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo. Artistic interest in signaling the magi’s foreign origins corresponded well with Christian exegeses that interpreted the adoration of the magi as symbolic of “heathen” peoples’ recognition of Christ. It was not until the tenth century in western Europe that the magi were reconceived as royal figures, in association with the reference of Isaiah 60:1-4 to the Messiah’s illumination of Gentiles and kings. In many works of art from this point onward, the magi have traded in their traditional caps and trousers for crowns and royal robes, as in the early fourteenth-century Saligny Hours (Morgan Library & Museum, MS. M.60, fol.8r).

From the early Middle Ages onward, the magi were increasingly conceived to be of different ages and geographical origins. In the eighth century, the unknown Irish author nicknamed the “Pseudo-Bede” set down these ideas in writing, describing the magi as of three ages—youth, maturity, and old age—that corresponded to three stages of the life cycle as described by Classical philosophers. Their representation in the ninth-century Stuttgart Psalter (Würtembergische Landesbibliothek, Bibl. Fol. 23, fol. 84r) observes this tradition, depicting them with a white beard, a dark beard, and no beard at all.

The Pseudo-Bede also described the magi as hailing from the three known parts of the medieval world: Europe, Asia, and Africa. These continents, which formed the basis for the typically tripartite division of medieval T-O maps, were also thought each to have been settled by one of Noah’s three sons, Ham, Shem, and Japeth, with whom medieval thinkers sometimes associated the division of humanity into African, Asian, and European “races.” The late medieval and early modern tradition of representing the magi with ethnic features that European artists tended to associate with each continent—Melchior as a white European, Caspar with Asian features, and Balthazar as a black African—can be traced to this chain of ideas. The opportunity to distinguish the magi as exotic foreigners through their physical appearance as well as through costume and other attributes inspired some of the most elaborate and imaginative portrayals of the later Middle Ages, among them Hieronymous Bosch’s famous 1510 Adoration of the Magi in the Prado Museum. In the Index, many similar images can be found by browsing the subject “Black Magus.”

Extensive image cycles developed around the story of the magi; these illustrate the several stages of their journey, including their questioning of Herod, their sighting of the star, and their arrival in Bethlehem, as well as the dream in which they are warned to avoid Herod and their journey homeward by another route. Over a dozen of these subjects, from “Magi, Adoration” to “Magi, Vision of Christ at Different Ages,” are catalogued in the Index. The most popular subject of all, for medieval and modern viewers alike, is the Adoration of the Magi, depicting the moment when the wise men render homage to the Christ Child in Bethlehem. Portrayals of this event range in both complexity and mood, from the charming, trousered travelers of early Christian tradition to the theatrical processions, replete with angels, gaily costumed servants, and trains of exotic animals (including camels!), of late medieval works like Gentile da Fabriano’s 1423 altarpiece of the Adoration, now in the Uffizi Gallery. Although we still have no idea where these wise guys came from, their presence never fails to bring magic and mystery to the traditional Christmas story.