We are pleased to announce the publication of the first book in the new series “Signa: Papers of the Index of Medieval Art at Princeton University,” co-published with Penn State University Press. The new volume, The Lives and Afterlives of Medieval Iconography, is co-edited by Pamela A. Patton and Henry D. Schilb and includes contributions from Kirk Ambrose, Charles Barber, Catherine Fernandez, Elina Gertsman, Jacqueline E. Jung, Dale Kinney, and D. Fairchild Ruggles. Congratulations and thank you to all our authors!

The second volume in the series, Beyond the Crossroads: Image, Meaning, and Method in Medieval Art, is currently in production.

By Jove! This year a special planetary alignment will occur on December 21st, also the Winter Solstice, when earth’s northern pole is at its greatest tilt away from the Sun. During this “Longest Night,” the planets Saturn and Jupiter will be within a tenth of a degree to one another, appearing to form a single “star.”

While an alignment of Saturn and Jupiter happens about every 20 years, when it happens in 2020 it will be one of the closest alignments of these two planets for over 800 years, and by some accounts since the year 1226.[1] The 1226 Saturn-Jupiter conjunction coincided with several historical milestones. In France, the reign of Louis IX, the only French king to be canonized by the Catholic Church, began following the death of his father Louis VIII. In Norway, the cleric Brother Robert translated the popular chivalric romance of Tristan and Iseult into Old Norse at the request of King Haakon IV. In the Kingdom of Georgia, the Sultan Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, last ruler of the Khwarezmian Empire, captured Tbilisi in the Battle of Garni. The mendicant friar, preacher, and later saint Francis of Assisi died on October 3rd. And according to Canadian astronomer and historian Vibert Douglas, the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan abruptly ended his military campaign in China, possibly owing to the phenomenon of five separate planetary conjunctions over the years 1226 and 1227.[2]

In the Middle Ages, the seven “planets”—Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Mercury, and the sun and moon—were important celestial bodies in the heavenly realm. Each was thought to have a distinctive personality, an idea still reflected in Gustav Holst’s orchestral suite The Planets, composed between 1914 and 1916. Holst calls Jupiter “The Bringer of Jollity” and Saturn—colloquially also known as “Father Time”—“The Bringer of Old Age.” These names doubtless influenced the artistic expression in the series of dance performances for Holst’s Planets by the Princeton University Ballet in 2018 linked above.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, was initially named after the ancient Roman god of thunder, and its planetary neighbor Saturn, the god of agriculture and harvest, was also Jupiter’s father. In Greek mythology they are Zeus and Cronus and were sometimes represented by medieval artists as luminous pointed stars, or solid spheres in concentric circles of earth-centered astronomical diagrams, as in this later copy of a Byzantine geocentric model of the cosmos (Fig. 1).

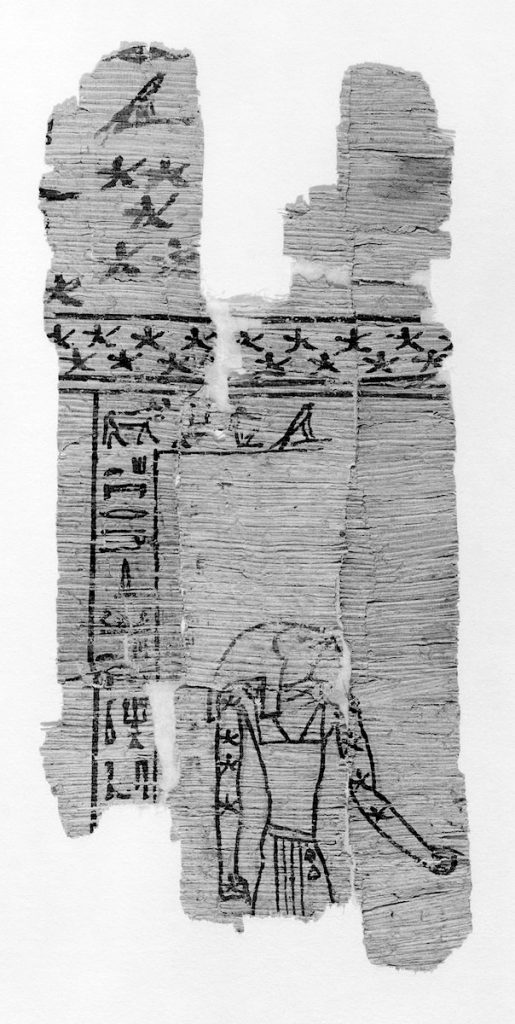

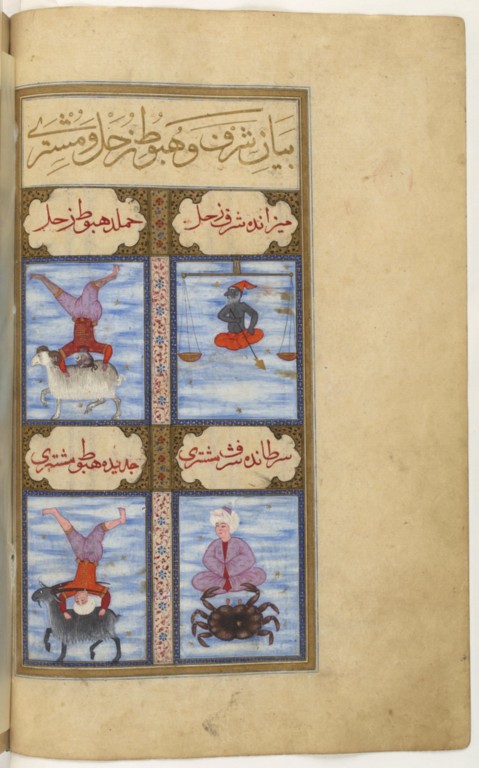

Representations of the planets are found in the artistic traditions of many cultures in which astronomy was an important science, including the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hellenistic, Indian, Byzantine, Islamic, and Chinese spheres. A possible early figuration of the planet Saturn can be seen on this ancient papyrus fragment in the Metropolitan Museum of Art as an Egyptian deity (Fig. 2). A much later figuration of the planets is found in this sixteenth century “Book of Felicity” (Matali’ al-saadet) made for Sultan Murad III (r. 1574–1595), now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which contains images of the “exaltation” and “dejection” of the planets—that is, when they are in apogee and perigee (Fig. 3). On folio 33v, Saturn’s exaltation in Libra is represented by the zodiacal scales, and his dejection in Aries shows him falling headfirst onto the back of a ram. The lower two vignettes similarly depict Jupiter’s exaltation in Cancer by pairing him with the zodiacal crab, and his dejection in Capricorn by tumbling onto a goat.[3]

In western European art, the planets were presented both as heavenly bodies and in symbolic form. In this late medieval manuscript of the Confessio Amantis (“The Lover’s Confession”) by John Gower, a small miniature of the planetary system, prefacing the part on Astronomy, contains the sun and moon with human faces among five gold and starry planets, the uppermost two labeled with their Latin names “Saturnus” and “Iubiter” (Fig. 4).

In Dante’s Divina Commedia, the spheres of heaven were represented by planets; Saturn was the seventh sphere and Jupiter the sixth. In this illustration of Paradiso 22, the scene of the “Heaven of Saturn” is portrayed by Beatrice and Dante welcoming five nude souls descending a ladder from a glowing red star with seven points (Fig. 5). Reading the Paradiso, we know that this level of heaven was reserved for the contemplanti, or the founders of monastic orders, “men who were kindled by that heat which brings to birth the blessed flowers and blessed fruits.”[4]

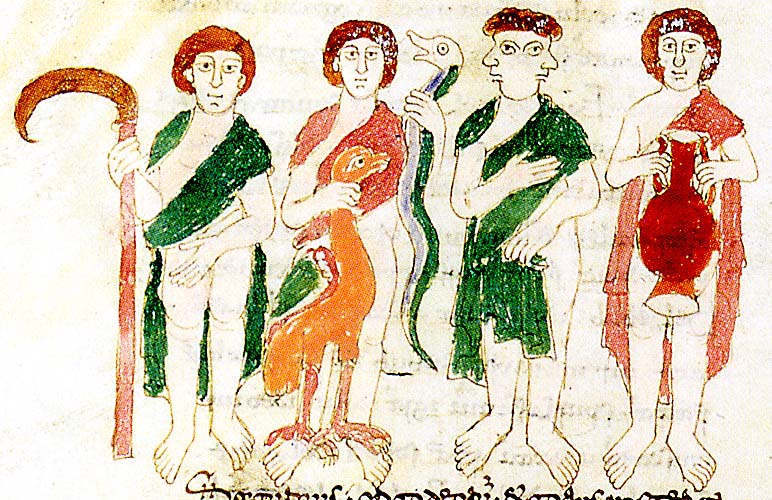

In other medieval works the planets of the cosmos (and sometimes their children!) were personified as human figures.[5] In some of the earliest examples, planets were depicted as crowned figures, triumphant generals, or wearing laurels, rayed headpieces or wings; such types appear on Roman coins and as bust-length personifications in illustrated poems known as carmina figurata.[6]

Some representations evoked the temperaments often associated with each planet. Associated with the ambivalent nature of melancholy, Saturn was often configured as an old man with a handheld sickle (or a more “modern” scythe) and with a cloak draped over his head, but he can also hold a shovel, a wheel, and small nude figure, which he raises up as if to devour, a reference to the Greek myth in which he swallowed his children.[7] Jupiter was seen as a protective deity: his iconography varies from the classical, bearded archetype of “Zeus Pater” (Zeus the Father), who brandishes lightning bolts, a celestial wheel, or other symbols of his power, to his personification as a bishop in a late fifteenth-century astronomical miscellany in the Getty Museum.[8]

In classical mythology it was held that Jupiter drove Saturn away from his celestial throne. A marginal scene in this ninth century Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen depicts this dramatic argument of the ancients (Fig. 6). Saturn is pursued by Jupiter both wielding an axe, illustrating the First Invective against Julian the Emperor, “… let Jove rebel against Saturn, following his sire’s example; that sweet stone and bitter slayer of tyrants …”[9] In an early eleventh century manuscript of Rabanus Maurus’s encyclopedic De Universo, one miniature depicts Saturn with a scythe, nearly as tall as he, and Jupiter holds a symbolic pair of attributes: an eagle for deified justice and a serpent representing the age-old struggle for it (Fig. 7).

Two highly emblematic representations of the planets Jupiter and Saturn appear in the Rheinish manuscript of the Von Dem Gang des Himmels und Sternen (“The Course of the Heavens and Stars”), forming its own “planetary conjunction” at the close of the book (the miniatures are on facing pages). Both planets, Saturn personified as a simple farmer and Jupiter as city patrician, are decorated with imagery from a number of astrological and zodiacal sources, including their corresponding symbols for Libra and Cancer (Figs. 8 & 9).

The Index of Medieval Art database includes much more in the way of celestial imagery, including subjects related to the iconography of the other planets, stars, zodiac symbols, and constellations. The database also can be keyword searched for other named astronomical objects, such as “Star of Bethlehem.” These examples appear in a wide variety of works of art, including almanacs, calendars, astrological treatises, constellation maps, zodiac cycles, and a variety of narrative and allegorical works, and across different media, cultures, and periods.

The planetary motions of Saturn and Jupiter have been described by astronomers, such as Newton, Kepler, and Laplace, as “The Great Inequality,” meaning that while Jupiter’s mean period of motion is continually increasing, Saturn’s is continually diminishing and falling further behind.[10] Thus, both planets have long been approaching each other in the same direction, yet with enormous discordance.

The year 2020 has had its own prelude of tumultuous moments leading up to this great planetary conjunction. As the globe still grapples with a challenging year, it’s easy to imagine this alignment of Saturn and Jupiter as a sort of “clash of the titans,” but when we look west in the sky just after sunset, let us recall that this special occurrence, a most rare ballet of the planets, also marks a new season that will bring more light to our days.

[1] O’Neill, Mike. “Don’t Miss It: Jupiter, Saturn Will Look Like Double Planet for First Time Since Middle Ages.” SciTechDaily, 23 Nov. 2020, https://scitechdaily.com/dont-miss-it-jupiter-saturn-will-look-like-double-planet-for-first-time-since-middle-ages/; Strickland, Ashley. “Jupiter and Saturn Will Look like a Double Planet Later This Month.” CNN, Cable News Network, 3 Dec. 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/12/03/world/jupiter-saturn-conjunction-2020-scn-trnd/index.html; Levenson, Michael. “Jupiter and Saturn Head for Closest Visible Alignment in 800 Years.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Dec. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/06/science/space/jupiter-saturn-align-christmas-star.html.

[2] Douglas, A. Vibert, “Historical Significance of Five Conjunctions, 1226–27,” Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 65 (1971): 129–132.

[3] See also this exquisite engraved and inlaid brass tray with personifications of planets made by Mamluk craftsmen and commissioned by a Sultan in Yemen in the early fourteenth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.1.60). For more on astronomy and astrology in the medieval Islamic world, see this essay by Marika Sardar: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/astr/hd_astr.htm.

[4] Paradiso 22, 47–48 accessed at Barolini, Teodolinda. “Paradiso 22: Controlled Orphism.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2014. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-22/. See also the Princeton Dante Project https://dante.princeton.edu/pdp/, with recent news and developments on the project here, https://humanities.princeton.edu/2020/11/29/2020-rapid-response-grant-literary-visualizations-reconstructs-imaginations-of-dantes-readers/.

[5] Discussion of the planets and their characteristics, temperaments, and affinities are found in many almanacs, planet books, and other cosmological treatises. See especially the classic Warburgian study by Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art (London: Nelson, 1964). Reissued by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019.

[6] The Index database records three examples of planetary carmen figuratem, all in the British Library, MS. Cott.Tib.B.V (fol. 44v), MS. Cott.Tib.C.I (fol. 33r), and MS. Harley 647 (fol. 13v).

[7] Klibanksy, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 197.

[8] For the Jupiter-Bishop on horseback see Getty Museum, MS. Ludwig XII 8 (83.MO.137), fol. 49v. See also the Art Stories post by Bryan C. Keene, “Written in the Stars: Astronomy and Astrology in Medieval Manuscripts,” Getty Iris Blog (30 April 2019), https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/written-in-the-stars-astronomy-and-astrology-in-medieval-manuscripts/.

[9] See lines 120–121: Gregory Nazianzen, “Julian the Emperor” (1888). Oration 4: First Invective Against Julian. The Tertullian Project, 14 Dec. 2020, http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/gregory_nazianzen_2_oration4.htm.

[10] Wilson, Curtis, “The Great Inequality of Jupiter and Saturn: From Kepler to Laplace,” Archive for History of Exact Sciences 33, no. 1/3 (1985): 15–290.

The year 2020, with its global pandemic, successive environmental crises, and sharp social and political divisions, has tested the patience, faith, and/or equilibrium of many people. As we approach the winter holidays, some will find solace in practicing gratitude—for challenges overcome, for crises averted, or simply for the love and support of those around them. It was not so different in the Middle Ages, when people in difficult circumstances also sought opportunities to consider or express gratitude, sometimes by pondering longstanding exemplars and sometimes by offering thanks of their own. Many of these left traces in medieval visual culture.

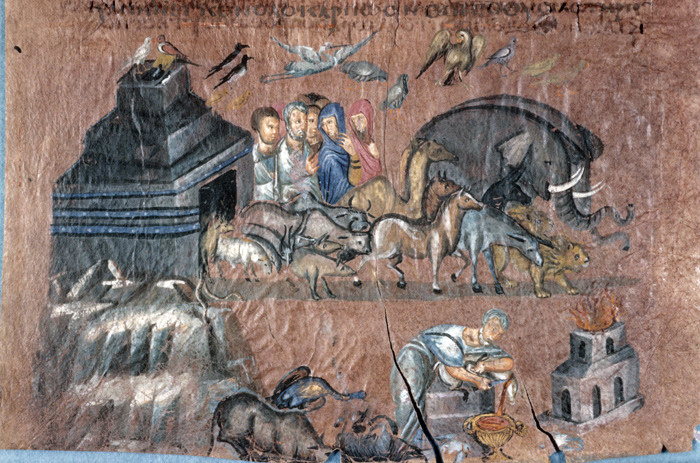

The most widely known medieval images of thanks-giving are those directed to the divine and holy figures to whom the faithful turned in troubled times. An example is the offering made by Noah after surviving the Great Flood, as described in Genesis 8:20 and represented in such works as the sixth-century Vienna Genesis [1]. In this purple-dyed luxury manuscript, the offering scene appears below a short parade of humans and animals, including elephants, lions, and camels, that issues from the ark onto dry land. Noah hunches gently over a sacrificial lamb he has placed on an altar as a thank-offering for humanity’s second chance.

A more creative expression of thanks appears in the Golden Haggadah [2], a fourteenth-century Passover manuscript in which Aaron’s sister Miriam leads the women of the Israelites in music-making and dance to thank the Lord for bringing them safely out of Egypt (Ex. 15:20–21).

Medieval Christians often gave visual thanks to the saints on behalf of those whom they were thought to have healed or rescued from danger. A thirteenth-century stained glass window in Canterbury cathedral records a number of miraculous cures performed by the relics of Saint Thomas Beckett, depicting the relieved victims of an arrow wound, malaria, madness, and even a nosebleed kneeling before the saint’s altar, their hands joined in thanks [3].

In the later Middle Ages, the Virgin Mary, thought to be the intercessor closest to God, earned special gratitude for her protection of the faithful: in the Cantigas de Santa María, the devotees who thank her for her miracles on behalf of the ill, the injured, and the unfortunate include the owner of an ailing silkworm colony, the recovery of which she celebrates by producing a beautiful silk textile that is presented to the Virgin by the king [4].

At times it was the work of art itself that embodied thanks offered to a holy helper. An intriguing example is a mid-sixth-century silver processional cross from Divirigi, now in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, which bears an inscription in Armenian that has been translated “In gratitude … [missing text] … offers to their intercessor St. George (of) Caginkom” [5]. Although the name of the patron is now lost and the reason for their offering remains unstated, the economic value of this substantial silver object suggests the depth of the unknown donor’s gratitude.

Creators and patrons sometimes added their thanks for the successful completion of a work of art. In an eleventh-century French manuscript of the poetic collection De sobrietate (Leiden, Universiteitsbib. BBL 190, fol. 16v), the poet Milo of Saint-Amand kneels before a church from which the hand of God issues in blessing; an inscription above reads “POETA GRA(TIA)S AGIT DEO PRO EXPLETO OPERE SUO” (The poet thanks God for the completion of his works) [6].

In the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the mihrab added to the structure in the 960s is framed by blue and gold mosaic inscriptions in Arabic that thank God for the successful expansion of the building to accommodate the faithful [7].

The belief that all good things come from God threads strongly through medieval visual culture. Nonetheless, some works record expressions of thanks between mortals—even if often these are legendary. An early sixteenth century tapestry from the Netherlands, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, depicts the story of Perseus and Andromeda in a series of scenes reading right to left [8]. While the climax of the narrative is Perseus’ slaying of the dragon that threatened the princess and her land, the sequence ends with the marriage of Andromeda to Perseus in thanks for his heroic deed, an arrangement for which the young couple appears to be, well, grateful.

The staff of the Index hope that the season finds our readers safe, in good health, and with something to give thanks for.

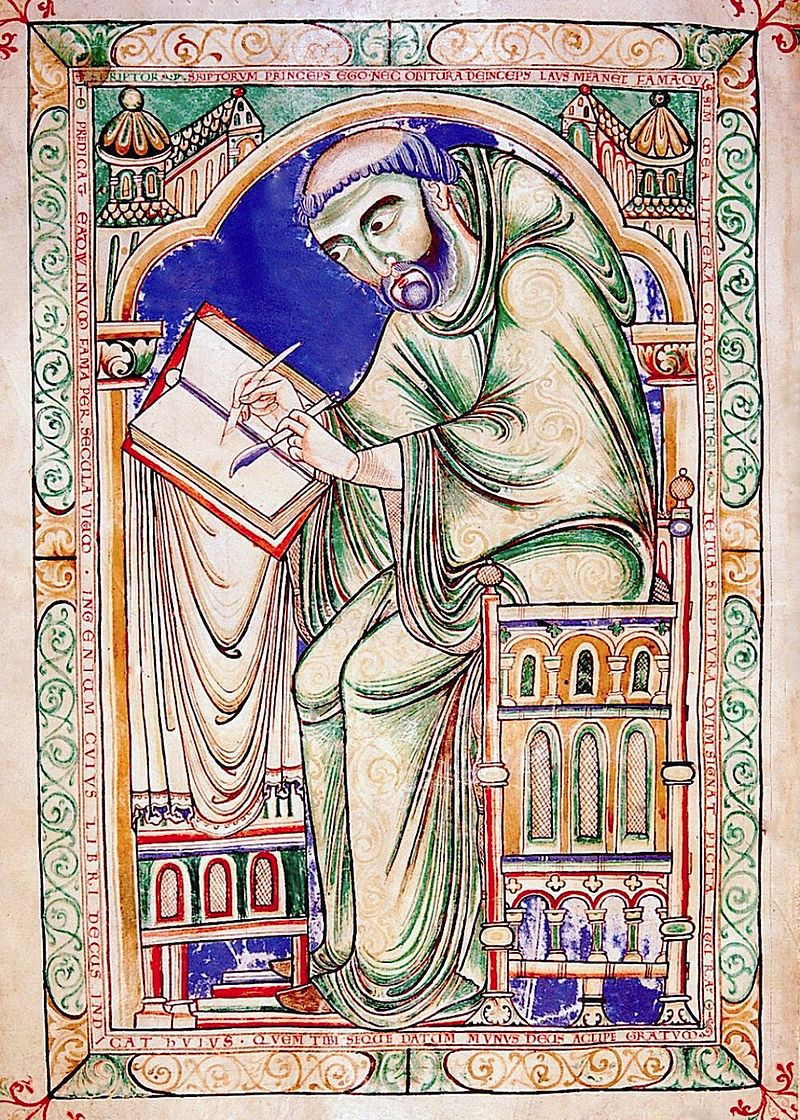

As the fall 2020 semester begins and the Index staff continue to work remotely, each of us connecting from different locations, our home libraries and desks have become essential tools in our research. They call to mind medieval images in which the scribe’s desk and well-stacked bookshelves are familiar iconographic attributes of the Evangelists, as well as theologians, scholars, physicians, and literati, as they labored in their study spaces (see Index subjects: Bookcase, Scholar, Physician, Literatus, and Philosopher Type). Their desks took a variety of forms and shapes, from tall book stands or lecterns, sometimes decorated with animals, birds, and foliage, to round or squat tables of a simpler design. Medieval images of scribes and writers often show the surfaces of their desks covered with open books or sheets, some with scrawled lines (search Index keyword: pseudo-inscriptions), inkhorns and inkpots, knives, pen cases, and a spare stylus or two.

Working in a modern study space, many of these similar tools are within my reach: pens, scissors, a pencil cup, and plenty of Post-it Notes containing my jotted reminders—arguably legible! My computer desktop is a hub for images of medieval works of art, articles, and spreadsheets that help organize my Index work. To the right of me, sits a modest collection of tomes (to name a few, Emile Mâle’s Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages; Roger Wieck’s Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art; Baxter’s Bestiaries and Their Users in the Middle Ages, and the catalogues The Splendor of the Word and The Golden Age of Ivory Gothic Carvings in North American Collections). Some books are my own and some are out on temporary loan from the Index’s research library and from Firestone Library, but all are bolstering this new environment of cataloguing and scholarship from home.

For Index research staff, this means that our working desktops (both physical and virtual) and our carefully curated home libraries (whether lining our walls or nested digitally into desktop folders) will support our ongoing remote activities. This semester, we will continue to pursue new art historical research for additions to the database, including works from the original print backfiles, from monumental mosaics to illuminated manuscripts and ivory objects. We remain focused on expanding the Index collection to present the rich array of iconography from the global Middle Ages. We will also continue to refine the database by building and improving work of art location authorities, further developing Index subject classifications that improve thematic browsing, and implementing the new hierarchical browse tool for researching the placement of medieval iconography within structures. Above all, we will remain available to support researchers at all levels in their use of the online Index database.

Wherever you may be this term—whether you feel like a monk in a cell or a monkey with an inkpot—we hope that you are well and looking forward to your study, surrounded by the tools of your scholarship. We look forward to hearing how we can help serve your research and teaching in the upcoming academic year.

Like many individuals and institutions, we at the Index of Medieval Art have been saddened and angered by the tragic and unjust deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, and Breonna Taylor in Kentucky, which highlight the persistent patterns of racist violence, harassment, and injustice that mark our nation’s history. As historians, we see the long roots of inequity and prejudice that gave rise to this legacy; as individuals, we commit to eradicating them.

We stand with Princeton University’s president, Christopher Eisgruber, in acknowledging our responsibility to oppose racism and to work to dismantle the systemic structures that allow it to survive. We join him in pursuing the commitment to diversity, inclusivity, and human rights that stands at the core of the university’s mission.

For the Index, this will include continuing to grapple with our own collection’s Eurocentric and colonialist past, as well as our responsibility to present the visual culture of the Middle Ages in a way that is expansive, inclusive, and respectful of the wide diversity of human artistic expression. It also means making it clear that the Index doors are open to all who wish to work and learn with us; inviting and amplifying new voices and perspectives in the work that we do; and creating opportunities that support academic, professional, and individual development for all.

We took modest steps toward these goals in the renaming of the Index in 2017, in updating and beginning to rethink its century-old taxonomy and cataloguing parameters, and through efforts to choose Index conference themes and speakers that are more widely representative of our field’s true diversity. However, we know that there is much more and harder work still to come. We commit to the self-reflection and dialogue that this work entails and look forward to making our values clear in deeds as well as words.

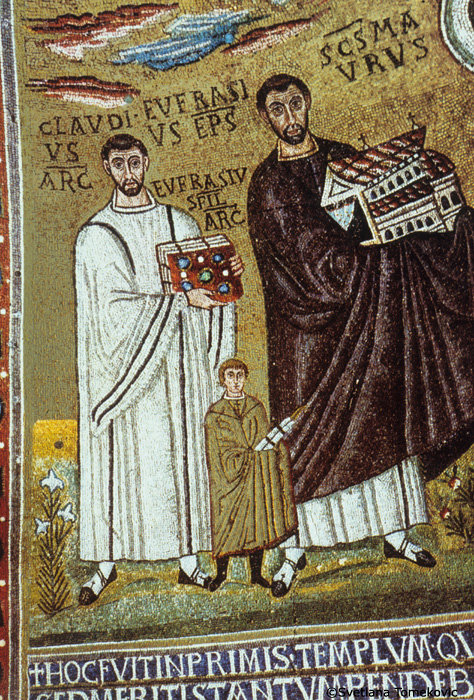

The Svetlana Tomeković Database of Byzantine Art is now live on the Index Digital Collections page. Users can once again browse this rich and extensive archive of photographs of Byzantine monumental art and architecture collected by Dr. Tomeković. There are nearly 4,000 images, many of them from little-studied buildings or sites that are hard to access. Reflecting the interests and specialization of Dr. Tomeković—who published extensively on wall paintings, iconography, and hagiography—the database includes photographs of sites ranging from Eastern Europe to the Mediterranean, including monuments in Greece, Serbia, the Republic of North Macedonia, Kosovo, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia, Italy, Turkey, Georgia, the Republic of Cyprus, and Israel.

The new application created to display this digital image collection allows researchers to browse the entirety of the Svetlana Tomeković Database with thumbnails or to explore the collection by location. Other Digital Image Collections hosted by the Index of Medieval Art are under construction and will be accessible in the coming months. The Svetlana Tomekovic Database of Byzantine Art can be found among the Digital Image Collections listed in the Resources menu on our web site. We hope you’ll explore this collection of images, and let us know what you think!

As always, for copyright and permission queries about images in the Tomeković Database, please contact Catherine Jolivet-Lévy at the Sorbonne in Paris (catjolivet@yahoo.fr).

In response to continued uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, the Index will postpone the “Fragments” conference until November 6, 2021. We are grateful that all the originally scheduled speakers envision being able to join us at that time.

The conference will address the role played by fragments and fragmentation in the medieval and modern understanding of works of art. Speakers will address such topics as the use or reuse of fragments in the creation of new works; quotation and replication as a kind of fragmentation; fragmentation of the perceptual or conceptual experience of a work; deliberate fragmentation or fragmentariness in works such as pilgrims’ tokens or votive objects; and the modern engagement with fragments as an attempt to reconstruct lost works of art, lost visual traditions, or lost cultural practices.

Andrea Achi, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Patricia Blessing, Princeton University

William Diebold, Reed College

Shirin Fozi, University of Pittsburgh

Gregor Kalas, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

Kathryn M. Rudy, University of Saint Andrews

Henry D. Schilb, Princeton University

Susanne Wittekind, Universität zu Köln

In reflecting on the crises precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Index of Medieval Art recognizes that many of our faithful blog readers are facing challenges that were unimaginable even a couple months ago. This has led us to consider how our predecessors must have worked through and responded to the various global catastrophes of the twentieth century. Since the founding of the Index in 1917, these have included the 1918 flu pandemic, two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Cold War, and countless other periods of political turmoil around the world. Through it all, the Index has never existed in isolation, and a sharp-eyed researcher can still find subtle traces of these global calamities in our records.

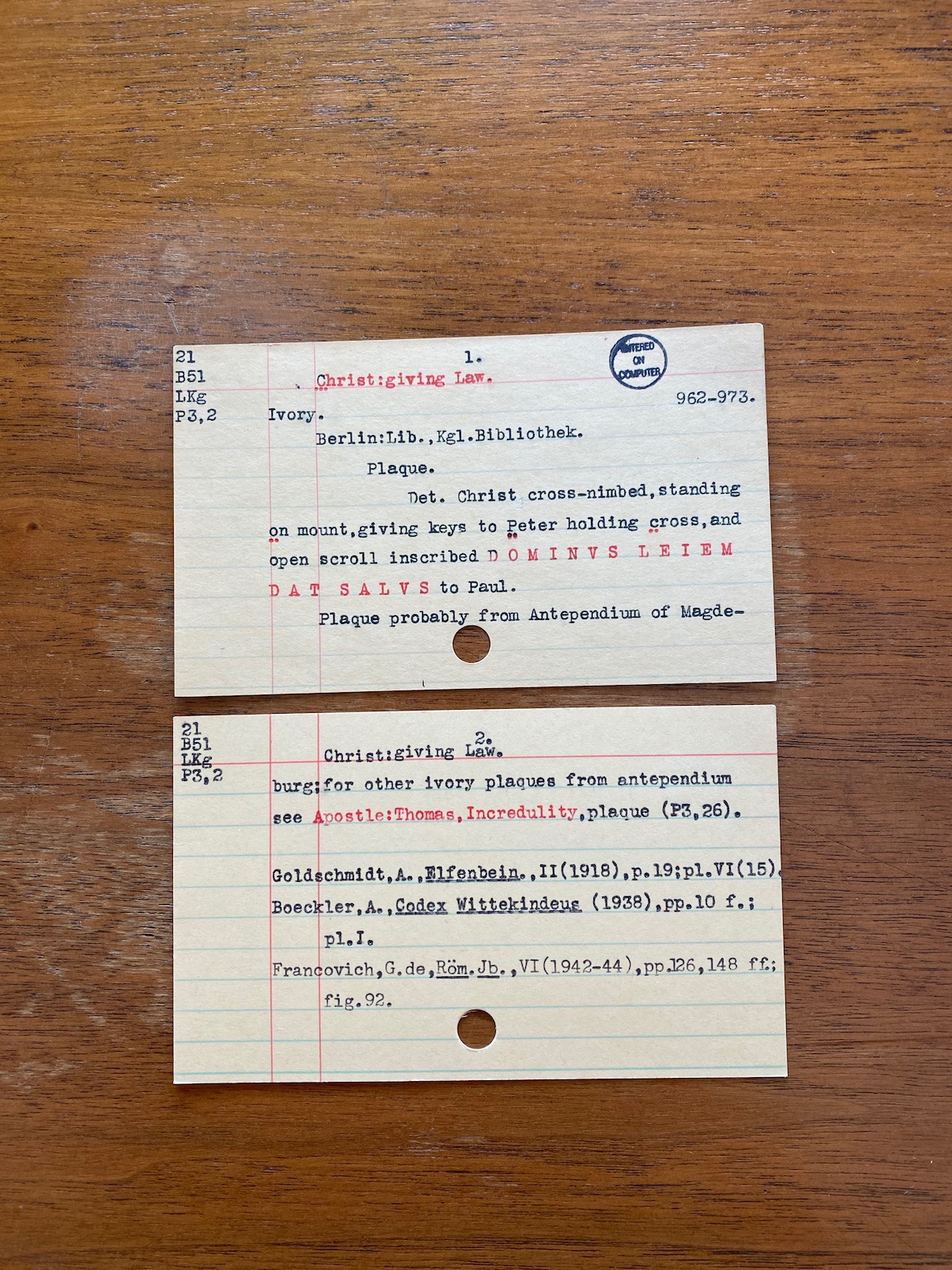

Consider the Index in its original physical (print) form. Visitors who have had the pleasure of thumbing through one of our five card catalogues may have missed a small but intriguing detail.

While the obverse of the main subject cards presented researchers with an iconographic synthesis (at least as it was understood in the twentieth century) in the form of a concise description of a work of art, the reverse sides recorded the creation and revision of the record itself, the handiwork of the scholar-cataloguers who composed all the information on the obverse.

Discreetly located in the corners of individual cards, humble date stamps mark the endpoints of the typically extensive research that went into the composition of all the main cards and secondary cards dedicated to any given monument in the Index. From a practical standpoint, these date stamps were meant to acknowledge any modifications made to individual work of art records, as new publications often generated changes to the identification of particular subjects within the description. Yet they also serve to remind us that Index work continued even during moments of international unrest. The sharp uptick in the number of records originating in the late thirties and forties, for example, not only underscores the exponential growth of the holdings within the physical card catalogue, but also highlights an awareness that many medieval monuments and objects in war zones were in danger of utter destruction.

One such case is a series of date stamps beginning in June of 1933, roughly four months after Hitler was appointed Reichskanzler of Germany, when an anonymous Index staff member added a record to the card catalogue related to one of the sixteen Magdeburg ivories, masterpieces of Ottonian art carved in the tenth century for a subsequently dismantled object—possibly an antependium—in Magdeburg cathedral. The ivory plaque in question bears a representation of the traditio legis, tersely described on the cards as “Christ cross-nimbed, standing on mount, giving keys to Peter holding cross, and open scroll inscribed DOMIVS LEIEM DAT SALVS (sic) to Paul.” The ivory’s location in 1933 was neatly typed above the description as an abbreviation for the Königliche Bibliothek, Berlin’s famed library, today known as the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. It arrived there as one of four other ivory plaques that adorned the book cover of the Codex Wittekindeus, a tenth-century manuscript from Fulda.

A subsequent date stamp confirms that the Index secured a photo of the plaque for the card catalogue on January 9, 1940, a seemingly mundane archival acquisition that might have generated a sense of unease in a research staff painfully cognizant of a Europe that was already in flames. Indeed, the building that housed the Magdeburg ivories and other treasures later sustained an enormous amount of damage from Allied bombing during the course of World War II. When modifications were made to the record in April of 1944, one can imagine that our cataloguer even contemplated whether the ivory plaque still existed at that moment.

That Index staff members were galvanized to participate in the war effort is clear. In 1942, Index director Helen Woodruff herself left the position that she had held since 1933 to join the Women’s Reserve of the United States Navy. Woodruff’s successor William Burke was a member of the Committee on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas, also known as the Dinsmoor Committee, which undertook the creation of maps and lists of monuments for the Allied armed forces in an effort to spare cultural treasures from bombing raids. While the accomplishments of Burke and other members of the “Monuments Men” remain justifiably well documented, it is also worth recognizing that Index staff members also must have felt driven to harness their knowledge of medieval art in the effort to record and preserve Europe’s medieval cultural patrimony. The rapid proliferation of records concerning endangered works of art, while not directly ameliorating human suffering in wartime, clearly acknowledges that the suffering of humanity and the annihilation of monuments were twin evils that both merited the world’s response.

Today we witness the international COVID-19 crisis from within the confines of our homes, electronically connected but physically separated from all the colleagues, students, works of art, museums, libraries, and archives that sustain us intellectually and imbue our own work with a sense of purpose. Although we Indexers have been able to maintain and grow our online database remotely during this difficult period, the physical card catalogue—now an historiographic monument in its own right—remains a testament to all the scholars of the previous century who continued to pursue their research through periods of darkness and uncertainty. Like many of you, we at the Index also look for strength and inspiration in the very manuscripts, monuments, and other precious objects that have by now borne witness to centuries of plagues, wars, and countless other tragedies. Together we must emulate the monuments that we study—and endure.

Catherine A. Fernandez, Art History Specialist

This conference will address the role played by fragments and fragmentation in the medieval and modern understanding of works of art. Speakers will address such topics as the use or reuse of fragments in the creation of new works; quotation and replication as a kind of fragmentation; fragmentation of the perceptual or conceptual experience of a work; deliberate fragmentation or fragmentariness in works such as pilgrims’ tokens or votive objects; and the modern engagement with fragments as an attempt to reconstruct lost works of art, lost visual traditions, or lost cultural practices.

Andrea Achi, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Patricia Blessing, Princeton University

William Diebold, Reed College

Shirin Fozi, University of Pittsburgh

Gregor Kalas, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

Kathryn M. Rudy, University of Saint Andrews

Henry D. Schilb, Princeton University

Susanne Wittekind, Universität zu Köln

Complete conference details, including schedule and a link to free registration, will be shared on this page in late summer.

In recognition of the challenges faced by students, faculty, and researchers now working on line in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Index of Medieval Art at Princeton University has made its online database open-access until June 1, 2020. As always, the database can be accessed at theindex.princeton.edu. Index staff will continue to respond to research inquiries sent via our inquiry form. We hope that this modest change will support researchers both old and new as they navigate teaching, learning, and scholarship during this trying time.