As part of Princeton University’s efforts to reduce the spread of COVID-19, the Index staff will be working remotely for the next several weeks and our reading room will be closed. Our online database will remain accessible, and we will be happy to respond by email or phone to any queries sent in using the research inquiries form. We will post an update when we’re able to return to campus. We thank you for your patience.

In northern climes, the beginning of February used to be reliably miserable. It was always the time of year when the sedentary heart of winter was covered in forgetful snow, and we took refuge indoors while the wasteland outside was feeding a little life with dried tubers (to paraphrase T.S. Eliot). Groundhog Day is in early February for a reason. Every year, in our collective longing for an early return of spring, we eagerly anticipate the meteorological insights of a skittish marmot. And so, despite the unseasonably warm temperatures in Princeton this week, we couldn’t help but explore some imagery traditionally associated with the month of February.

In many manuscript calendar illustrations, the occupational image for February depicts an interior scene, a room in which figures warm themselves before a fireplace. Seated at the hearth, a female servant, or perhaps the woman of the house, stokes the fire. Often in such scenes, a man sits at a table spread with food and dishes. The Index of Medieval Art subject heading identifies this scene as the “Labors of the Month, February.” Certain components of this subject, such as “Fireplace,” “Table,” and “Feasting,” also have their own subject designations.

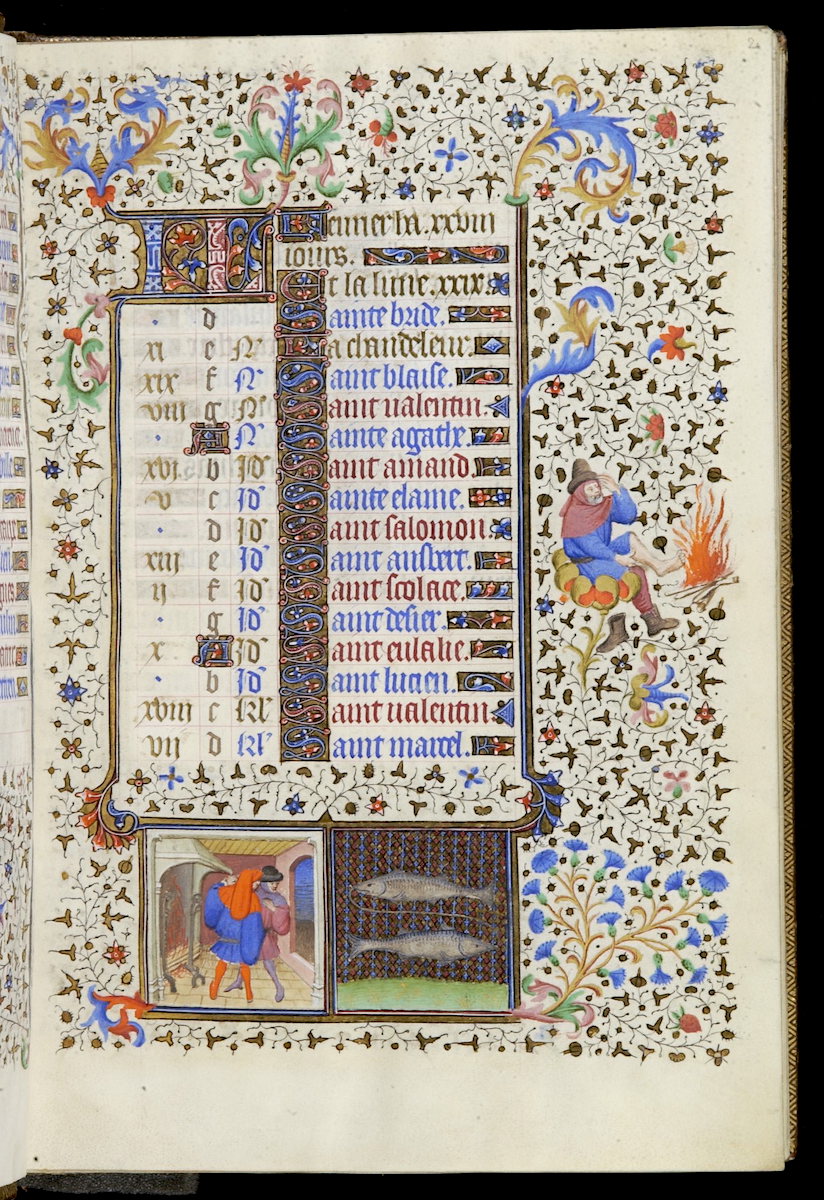

Other attributes common to the February warming scenes are figures performing such actions as blowing a bellows at the fire, cooking food in a pot over the flames, carrying bundled firewood indoors, or wearing heavy furs. A marginal miniature in the calendar of a fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Burgundy depicts a typical February scene with several of these domestic elements: a woman wearing a veiled headdress stokes a glowing fire in a simple stone fireplace while, behind her, a warmly dressed man seated at a draped table clings to a morsel of food (Fig. 1).

Searching the Index of Medieval Art database with simple keywords such as “fireplace,” and using the Subject Filter for “Labors of the Month, February,” will return a little more than seventy work of art records. Most of them appear in illuminated manuscripts. One such fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Paris or Flanders contains a February calendar page with two square miniatures of equal size in the lower margin. One of these paired miniatures shows the typical interior occupation of February, figures by the fire. The other shows the usual zodiac sign, Pisces, as a pair of fish lying head to tail with a line connecting them by their mouths. In the right margin, the artist created a comical moment: among the densely scrolled foliate borders, a man sitting on a fantastic flower raises his bare left foot toward some blazing logs (Fig. 2). In February, even marginalia need to warm their toes!

Other database filters will discover results illustrating February in different media, such as a man warming himself in the quatrefoil stone relief sculpture on the west façade of Amiens Cathedral. While this February figure sits and adjusts logs on the fire, his shoes are neatly placed in the foreground (Fig. 3). As is common for all twelve labors of the months, iconographic variants occur among these images, and monthly tasks are not fixed. Indoor cold weather occupations—including feasting, cooking, and baking—can be found in the previous months of January and December, often in similar compositions with fireplaces. February illustrations may also show outdoor scenes, such as slaughtering animals, fishing, digging fields, or pruning vines.

Keeping warm and dry during the winter months was a matter of survival for medieval people. Even today our good health and happiness are at risk in the winter. While its fires are long extinguished, this fine fifteenth- or sixteenth-century French limestone fireplace, today on display in the Met Cloisters, was likely once the architectural centerpiece of a home, and we can still imagine its appealing warmth (Fig. 4). Whether you are enjoying a restfully sedentary season or the official start of the spring semester has you thoroughly engaged in your own labors of the month, we wish you a warm and happy February!

The Index of Medieval Art wishes all our faithful blog readers a joyful New Year! Whether you are currently recovering from the excesses of New Year’s Eve, eating certain foods that bring good luck, contemplating a new exercise regime (that you will abandon by Groundhog Day), or arguing with your most pedantic family member (unless that happens to be you) over when the new decade really begins, we Indexers would like to take the time to examine some medieval New Year festivities for your reading pleasure today.

For the Valois courts in late medieval France, the new year was celebrated by partaking in the étrennes, an annual gift-giving ritual with roots in Roman Antiquity. Originating from the Latin strena, the term étrenne encompassed both the ritual act of gift giving as well as the actual gifts themselves.[1] Thus, on New Year’s Day the highly dysfunctional yet fashionable members of Valois nobility gave one another exquisitely-made, begemmed objects known as joyaux. Few of these resplendent pieces are extant today, but Valois inventories preserve a wealth of information on the kinds of items that were presented for the étrennes and the identities of their original donors and recipients.

The only surviving non-manuscript étrenne is the Göldene Rössl, a multifigured masterpiece of fifteenth-century Parisian gold- and enamelwork. Positioned atop a golden platform, the Virgin and Child loom large beneath a gem-encrusted trellis, towering over delicate representations of infant saints and the kneeling figures of King Charles VI and a knight. Below this assemblage stands a small, white horse led by a page in elegant clothing.

Beyond its obvious material value, the Göldene Rössl also serves as one of the finest examples of émail en ronde bosse, an enamel technique that showcases varying gradations of color and translucency. Presented by Isabeau of Bavaria to her husband Charles VI on New Year’s Day in 1405, the object exemplifies the kinds of sumptuous objects exchanged by members of the Valois courts for the étrennes.

The kneeling figure of Charles VI venerating the Virgin and Christ Child exudes a sense of decorum, sanctity, and solemnity that belies the reality of the ruler’s frequent bouts of madness described in early fifteenth-century sources. The Index includes other portraits of the king, identified within the database as the subject Charles VI of France. Other notable Index Valois subjects include Philip the Bold; Charles V of France, the Wise; and, of course, John, Duke of Berry (Jean de Berry). Curiously enough, the most famous portrait of the duke of Berry, namely, the January calendar page of the Très Riches Heures, does not show a representation of gift exchange. Nevertheless, the luxurious metalwork on display and the sartorial finery of the duke and his courtiers depicted in the illumination underscore the absolute lavishness of the New Year’s celebrations.

Lest we assume that bad gift-giving behavior developed in the modern world, consider the documented foibles of the Valois nobility. For those of us who feel guilty about splurging on items for ourselves during the Black Friday sales, take comfort that Louis of Orléans gave himself a fabulous sword “in the Venetian style,” ornamented with gold and precious stones, one New Year’s Day, or that during the étrennes of 1404, Philip the Bold gifted himself an exquisite gold nef (ship model) covered in gems and pearls that cost a minor fortune.[1]

Have a friend or family member who likes to give you weird “joke” gifts for Christmas or Hanukkah? The Limbourg brothers crafted a fake book for Jean de Berry made from a single block of wood affixed with a faux binding and clasp. Hilarity must have ensued when their illustrious patron attempted to open the trompe l’oeil volume in front of other members of his court on the first of January in 1411.[2]

Forget to buy something for that special someone in your life? Jean de Berry’s wife Jeanne de Boulogne remained, as Michael Camille astutely observed, “notoriously absent [emphasis mine] from the ‘give and take’ of the inventories” that carefully recorded all of the gifts presented during the annual festivities.[3] The duke of Berry also habitually committed the common sin of regifting. As the duke’s inventories attest, many of the joyaux that he received during the étrennes were later regifted to other individuals or were even melted down for the creation of new objects. Nor was he the only member of the family to do so, and even the Göldene Rössl met a similar fate. Only a few months after receiving the piece, Charles VI (always low on funds) pledged it to his brother-in-law Louis of Bavaria as a partial payment for his annual pension![4]

In spite of the depressing historical realities surrounding these ostentatious objects, they will always have a hold on the modern imagination. And why not? The future is golden, dear readers. Happy 2020!

[1] Buettner, “Past Presents,” 608, 623, n. 71.

[2] Michael Camille, “‘For Our Devotion and Pleasure:’ The Sexual Objects of Jean de Berry,” Art History 24, no. 2 (2001): 181.

[3] Camille, “‘For Our Devotion and Pleasure,’” 180.

[4] Buettner, “Past Presents,” 607. For a more in-depth analysis on the creation and history of this amazing object, see Reinhold Baumstark and Renate Eikelman, eds., Das Göldene Rössl: Ein Meisterwerk der Pariser Hofkunst um 1400 (Munich: Hirmer, 1995).

Contributed by Catherine A. Fernandez, Art History Specialist.

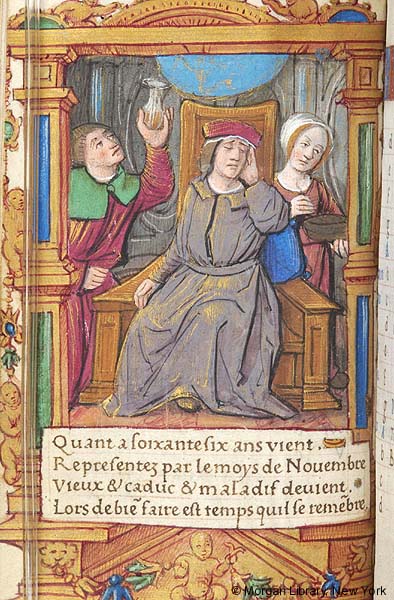

As the calendar approaches the winter solstice, our thoughts turn to Saint Lucy, whose feast day on December 13 shares many of the same themes of light and hope. A modern viewer’s first encounter with medieval images of the early Christian saint Lucy might seem somewhat gruesome. The Index holds 139 records with the subject Lucy of Syracuse, and in many, as you will notice, she is represented holding a dish or tray bearing two eyes (Fig.1). This peculiar attribute derives from her hagiography, in the course of which the saint’s eyes were gouged out.

The narratives related to this eye-gouging seem to have developed only in the later Middle Ages, and they are inconsistent: some recount that her Roman persecutors tore her eyes out as part of her martyrdom; others claim that she herself did it to present them to an unwelcome suitor who admired her beauty—take your pick!

In case you were wondering—and those of you who are acquainted with fourth-century martyrs will probably have already guessed it—in neither version of the story was eye-gouging the cause of Lucy’s death. As is almost always the case in such stories, after several other tortures, her head was cut off. This leads us to the other way Lucy is often represented, either holding a dagger or with a dagger thrust into her throat (Fig.2).

But there is much more to the Lucy story than martyrdom details. According to her vita, Lucy was an early Christian during the reign of Diocletian. She decided to devote her life to God and leave her inheritance to the poor. But without her knowing, Eutychia, her mother, had already arranged her marriage. When she called off the wedding, her suitor was indignant (no surprise there) and in revenge reported her as a Christian to the Roman authorities. Although this part of Lucy’s life is less often represented than her martyrdom, some images of this period were also produced. An example is the Index subject Lucy of Syracuse, Giving Dower to Poor. As depicted by Giovanni di Bartolommeo Cristiani (active 1367–1398), Lucy appears flanked by Eutychia (Fig.3). Her left hand reaches into a decorated purse, while with her right hand she offers a coin to a man leaning on a crutch and cane. He is followed by a veiled woman and five men, all wearing hats, one with an arm in a sling and a wooden leg, and two holding canes, one probably blind. All, presumably, will be the beneficiaries of Lucy’s generosity.

Having heard that Lucy was a Christian, Paschasius, the Governor of Syracuse, commanded that she be brought to a brothel for prostitution. But when the guards tried to seize her, her body became too heavy to be lifted. In response they decided to tie her to several oxen to drag her, but she would remain immobile. This is the episode represented by Bartolo di Fredi Montalcino in the second half of the fourteenth century (Fig.4). Paschasius, seated and crowned, is at the far left, while Lucy stands at the center of the composition, with her tormentor behind her; she is tied with ropes to three oxen and a group of men trying desperately to make her move.

Since she was unmovable, her attackers next decided to cut bundles of wood and burn her alive. Although this might have seemed a solid choice, it also failed: Lucy remained unscathed and unburned. Eventually, as represented in the illumination for her feast day in the Menologion of Basil II (976–1025), she was martyred by sword in ca.304, in Syracuse in Sicily (Fig.5).

In addition to the Index subject Lucy of Syracuse, Martyrdom, Saint Lucy can also be found tagged with subjects Martyrdom, by Beheading and Sword (Martyrdom Instrument). Yes, at the Index we like to be thorough! If you’re interested in learning more about how martyrdom was represented in the Middle Ages, you can find all martyrdom types in the Index Subject browse list, where you will find instances of martyrdom by boiling oil, disembowelment, dragging by horse, and hanging by hair, for example. If searching for the instruments, you also can go to our Subject Classification and click Religious Subjects > Christianity > Saints > Martyrdom Instruments.

But enough about martyrdom. Medieval and modern devotion to Saint Lucy is deeply tied to her name: Lucia in Latin, which shares the root luc with the Latin word for light, lux, and by extension with sight. Because of this connection, she is often shown with a torch or a burning lamp, as in this thirteenth-century panel painting, today in the Musée de Grenoble (Fig.6). Lucy appears here richly dressed as a Byzantine empress, wearing a crown with precious jewels and pendula of pearls, and holds a lighted lamp in her right hand. She is flanked by two winged angels swinging censers, emerging from above. On the foreground, to the left, the female donor, Angila Cerroni, veiled, kneels with her joined hands raised in prayer.

Just like Angila Cerroni, many other devotees found themselves invoking Lucy against blindness, eye disease, sore throat, fire, and poverty; penitent prostitutes also called on her. Perhaps because Lucy’s feast day, December 13, originally coincided with the winter solstice, marking the shortest day of the year, she is especially celebrated in the Northern Hemisphere. In Scandinavian tradition even today, the oldest daughter in the family may dress in white and wear a crown of candles on her head, bringing light, just like Lucy, in the darkness of winter.

Contributed by M. Alessia Rossi, Art History Specialist.

We have recently learned of an incident that occurred at the reception following the recent Index conference “Art, Power, and Resistance in the Middle Ages,” during which an attendee not affiliated with Princeton University behaved uncivilly and aggressively toward another individual. The attendee’s remarks targeted the individual’s identity in a way that was inappropriate in any context. We wish to make it clear that conduct of this kind will not be tolerated at any event sponsored by the Index of Medieval Art.

Our recent conferences have encouraged speakers to address those ways in which the study of medieval images and ideas might shed light on contemporary social, cultural, and political issues, and several have done so. Their presentations might surprise, or even provoke intellectual discomfort in, any of our listeners. But as medieval scholars themselves well recognized, discomfort and learning often go hand in hand, and it is by exploring the sic et non of differing points of view that we move knowledge forward. Attendees at Index conferences should always feel welcome to raise questions that express disagreement with a speaker during Q&A, but both there and in all conference events, they are expected to maintain the same civil and respectful standards of discourse that are the norm in our profession, as outlined by such organizations as the International Center of Medieval Art (http://www.medievalart.org/about-us) and the Medieval Academy of America (https://www.medievalacademy.org/).

Any attendee who wishes to share a concern about the topic or content of a lecture given at an Index conference may do so by contacting the Index director, Pamela Patton, at ppatton@princeton.edu.

If you celebrate Thanksgiving in the United States, decorations for the feast might well include a representation of a cornucopia, a literal “horn of plenty” (Latin cornu + copiae) spilling over with fruits, vegetables, and flowers suggestive of a generous harvest. Wondering where this symbol came from and how it got onto Aunt Marian’s Thanksgiving table? Wonder no more: armed with 139 online records for the subject “cornucopia,” the Index is here to help.

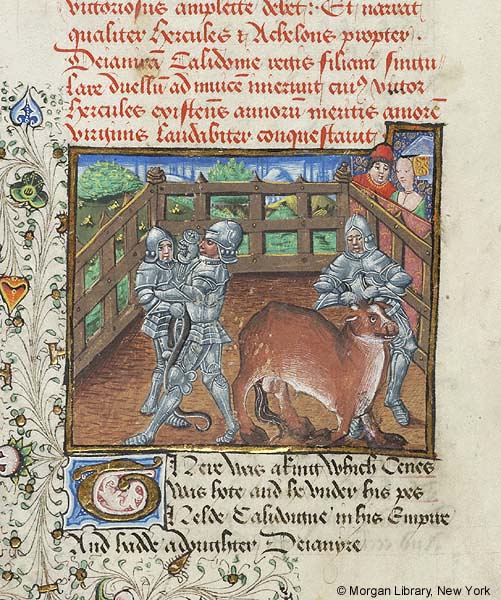

The cornucopia originated in classical mythology, where it bore connotations of plenty and good fortune. Explanations of its origins vary: according to Ovid’s Metamorphoses (ix.8), the Greek demigod Herakles tore the horn from the head of the shapeshifting river god Achelous, whom he wrestled to win the hand of Achelous’s daughter Deianira. Heracles then gave it to the Naiads, who turned it into a horn that produced an endless supply of foodstuffs. The Index records include an engagingly “modernized” version of this scene in a fifteenth-century manuscript of John Gower’s Confessio Amantis now in the Morgan Library (Fig. 1). Several other ancient sources attribute the horn to the goat Amalthea, which suckled Zeus on Crete when he was hidden there by his mother Rhea from his child-eating father Cronus. When Zeus accidentally broke off one of the goat’s horns, it became imbued with the power to be filled with whatever the owner might desire.

The positive connotations of the cornucopia made it a popular classical attribute. Usually configured as a twisted horn from which fruit, flowers, or other plants emerged, it became associated with a number of deities and personifications, including Demeter, Gaia, Persephone, and Tyche, the Roman Fortuna. A Roman statue of Tyche-Fortuna from the first or second century CE, today restored with the portrait head of an unknown woman (Metropolitan Museum of Art), portrays the goddess holding a ship’s rudder, alluding to how fortune steers human fate, in her right hand and a cornucopia filled with fruit in her left (Fig. 2).

A rendering of Fortuna with these attributes also can be found in a fresco from the synagogue of Dura Europos, produced by 244 CE (National Museum of Damascus). One of many classical references found in these early Jewish wall paintings, it appears as a faint line drawing on the right lower panel of the central door (Fig 3). In both these cases, the overflowing horn suggests a hope for the abundance that comes from good fortune.

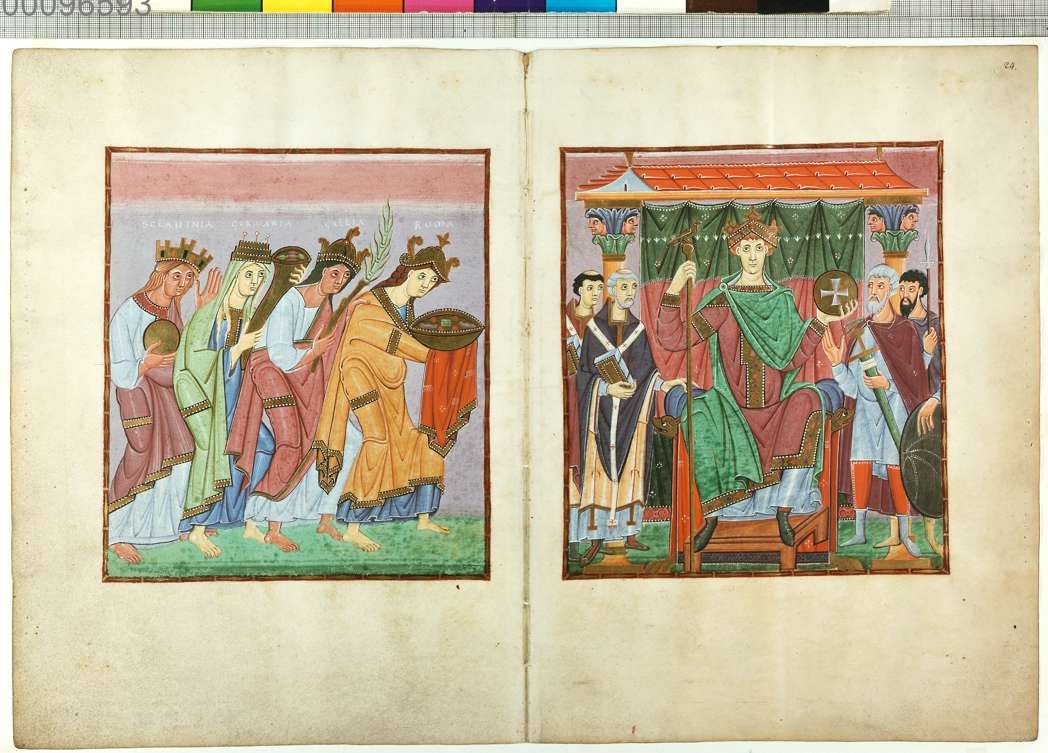

During the Middle Ages, the symbolic associations of the cornucopia expanded significantly. While it could continue to promise good fortune, it also appeared as a sign of homage, as in the Gospels of Otto III, produced in the Holy Roman Empire around the year 1000 (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek). Here, the four personified provinces who bring tribute to the emperor include a personification of Germania holding a golden cornucopia (Fig. 4); although no fruits are visible, its implications of earthly abundance would have made it an appropriate offering for the imperial ruler.

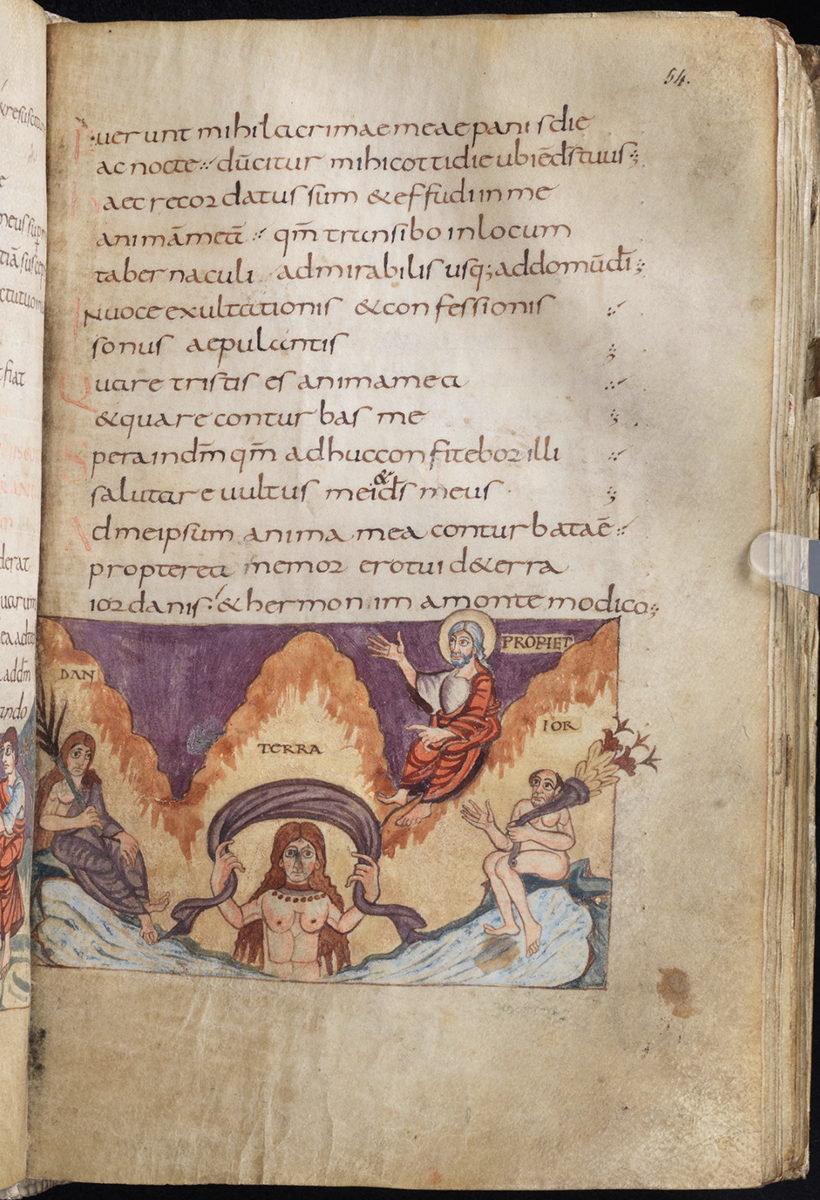

The cornucopia can also be found as an attribute of personified geographical locations, such as cities or waterways. On the right-hand leaf of a fifth-century diptych representing the cities of Rome and Constantinople (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), the figure representing the Byzantine capital holds a large cornucopia in her left hand (Fig. 5); in the Stuttgart Psalter (Württemburgische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart), the personified river Jordan holds a cornucopia sprouting leaves and flowers (Fig. 6).

The cornucopia could also represent more abstract values, including charity, hope, and abundance itself. The portrayal of Abundantia as a lesser goddess who holds a cornucopia originated in Roman tradition, and it persisted throughout the Middle Ages as a secular personification with very similar iconography.

In the early modern era, the formula was further popularized by artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, whose majestic red-robed Abundantia, painted circa 1630, spills an array of apples, grapes, figs, and other fall fruits from a cornucopia to the ground, to the delight of the putti who scramble for them at her feet (Fig. 7). This may be the formulation of the horn of plenty most familiar to modern viewers, for whom a cornucopia centerpiece suggests both the gratitude for good fortune and the spirit of generosity that both stand at the core of the modern Thanksgiving holiday.

As a victorious angel, defender, and leader of heavenly armies, Michael the Archangel is often depicted in medieval art as an armored soldier carrying such arms as a cross-inscribed shield, cross-staff, or the sword or spear he typically employs to fight the dragon in the “great battle of heaven” (Apocalypse 12:7–9; see the Index subject Apocalypse, Dragon Attacked by Michael). Outside of the apocalyptic combat scene, Michael also may be shown trampling and piercing the dragon as part of his overall iconography. This figuration of Michael as the triumphant archangel lent a devotional and meditative aspect to his veneration as an overcomer of evil, as is often clear in images related to the Christian feast of Michaelmas. The feast’s name in English derived from “Michael’s Mass” and is traditionally observed in some Western churches on the 29th of September. While Michaelmas was primarily celebrated to acknowledge the works of Michael the Archangel, this feast also celebrated the help and intercession of all angels. Michaelmas also bore secular significance for medieval people as a “quarter day” of the financial year, which signaled the fulfillment of various business obligations, and the close of the agricultural year (For more on this holiday, see Ben Johnson, Michaelmas, The Blog of Historic UK).

At this time of Michaelmas, a dive into the online collection of the Index of Medieval Art reveals a wealth of examples tied to the iconography of the revered archangel. The most common representation is of Michael the Archangel fighting the dragon. In the language of the Index, that’s Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Dragon. This subject heading is attached to nearly 300 works of art in the database applied to a variety of media, including a Romanesque limestone relief panel from Burgundy, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris (Fig. 1). A closely related subject, Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Satan, is applied to works of art in which the dragon has morphed into a devilish creature, usually shown with horns and clawed feet. Like the hapless dragon, this creature is similarly impaled and trampled! Exploring these two similar subjects reveals a later preference for the literal depiction of devils in place of dragons. Michael the Archangel also features in other important episodes, such as the biblical narrative of the Fall of Angels and the Last Judgment of Christ (Figs. 2 & 3). In Last Judgment scenes, Michael the Archangel is often shown holding the scales of justice laden with good and bad souls (See the Index subject Weighing of Soul).

A fifteenth-century alabaster panel from England combines many aspects of Michael’s typical iconography: here, wearing a suit of armor that resembles feathers, he also bears a shield and raises his sword over the vanquished dragon. One weighing pan of his scales remains, holding a devil head, while behind him, a crowned Virgin intercedes to emphasize mercy with justice (Fig. 4).

In the Index database, Michael the Archangel is by far the best represented of the archangels, with thirteen subjects covering his various roles, from intercessor and commanding soldier to apparition in visions and legends. A common legendary context for Michael is that of the “Runaway Bull” in the Golden Legend. According to the legend, a wayward bull belonging to Garganus, a wealthy man from Siponto, is miraculously saved from the shot of an arrow, which instead reversed in midair and killed the huntsman. As an explanation for this strange occurrence, Michael the Archangel appears to a local bishop to reinforce the idea of grace at the bull’s saving and to tell him to build a church in his honor (Fig. 5). The hilltop sanctuary of San Michele del Gargano is still a popular site of pilgrimage in the town of Monte Sant’Angelo in southern Italy.

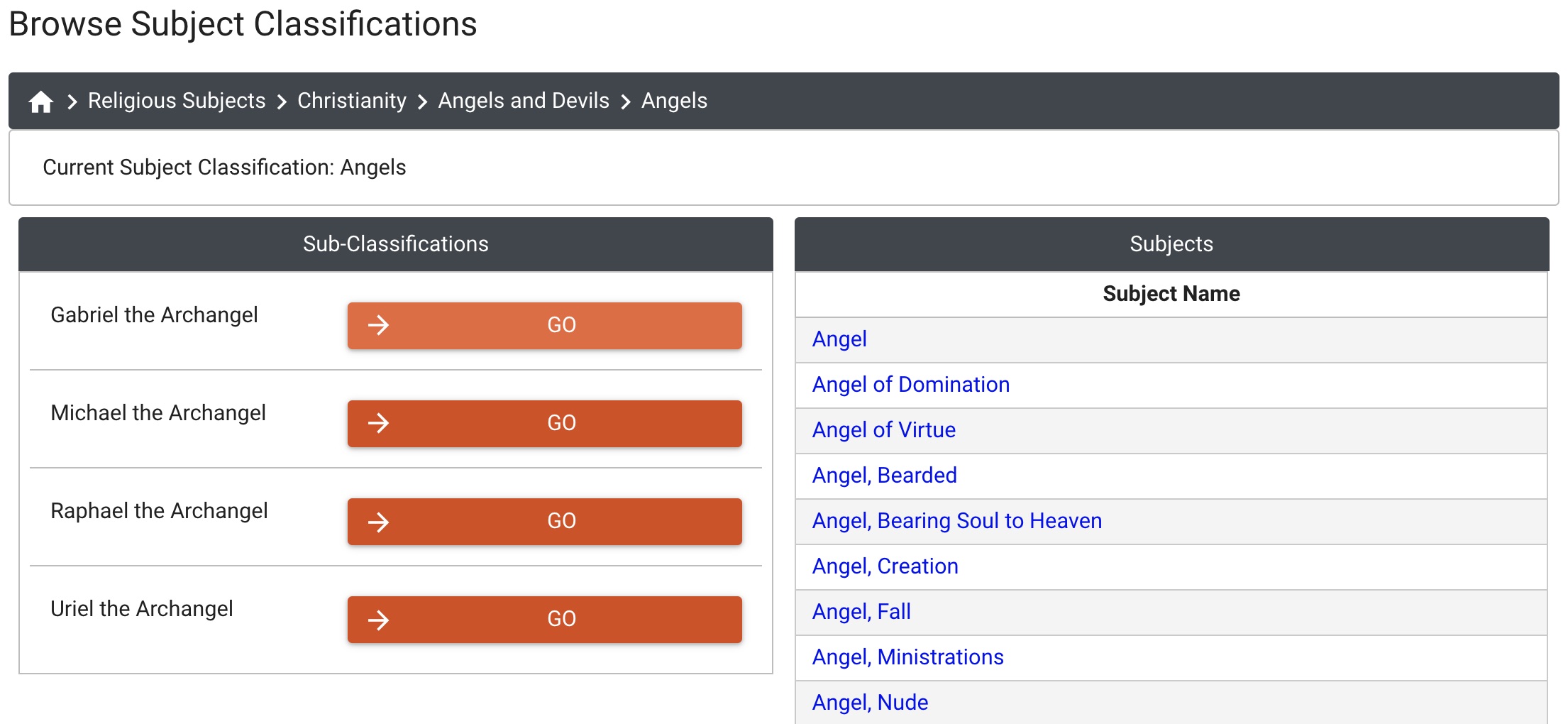

For a more general overview of the iconography of angels in the Index database, we encourage you to browse sections of the new subject classification network by clicking “Browse” and proceeding to the link for “Subject Classification.” From here, click on Religious Subjects, then Christianity, then Angels and Devils. In the sub-group of Angels, you will encounter a list of over twenty iconographic headings associated with various angels, including seraphs, cherubs, and several more subjects for angels engaged in specific actions, such as “Protecting Soul” and “Pursuing Devil.” On the left are further divisions for the four major archangels of Christian angelology—Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, and Michael—which list the individual subjects related to each. At the bottom of each authority for these subjects, you’ll see a bar for “Work of Art References” that will take you to the relevant work of art records.

Registration is now open for the Fall Index conference, “Art, Power, and Resistance in the Middle Ages,” November 16, 2019. To view the speakers and schedule and link to the registration form, please click the link below.

As always, Index conference admission is free and open to the public; your registration is appreciated to ensure adequate seating and refreshments. https://ima.princeton.edu/conferences/

Detail, Arch of the Transfiguration Apse Mosaic, 6th century.

Church of the Transfiguration, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt

Location, Location, Location: In-Situ Iconography within the Medieval Built Environment

55th International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo MI, May 7-12, 2020

Proposal Deadline: September 15, 2019

Please consider submitting a paper to the next Index-sponsored session at the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo! This year’s session concerns the role of iconography within the built environment and has been organized by Index specialist Catherine Fernandez.

Session description: Almost all architectural components in the Middle Ages had the potential to bear images. Walls, arches, portals, domes, capitals, and other structural supports proffered surfaces for the deployment of narratives, portraits, drolleries, and ornament. Iconography in such locations not only figured prominently in relation to ephemeral occurrences, such as the performance of the liturgy, processions, and other civic rituals; it also underscored more permanent demarcations within urban cityscapes and rural landscapes by recalling specific events or established cultural or environmental conditions, both historical and legendary. This session invites proposals that explore the integration of in-situ iconography within the medieval built environment. We welcome papers that consider the relationship between the location of imagery within a monument and related external factors such as ritual, topography, patronage, institutional or civic memory, and regional identit(ies). Papers may consider specific case studies or address more theoretical concerns.

Please send abstracts of no more than 300 words with a completed Participant Information Form (https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/submissions) to caf3@princeton.edu) by September 15, 2019.

Further information about the Congress can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress

Information on awards granted to defray the travel costs of speakers can be found here: https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/awards

The ways in which scholars research the iconographic traditions of the Middle Ages is continuously evolving. In order to address this, the Index of Medieval Art organized and sponsored a roundtable, Encountering Medieval Iconography in the Twenty-First Century: Scholarship, Social Media, and Digital Methods, at the 54th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. The five panelists briefly presented on the ways in which they incorporated iconography into their teaching, research, and curatorial work. They then participated in a discussion of how they use and develop online resources, such as image databases, to reach students and researchers. The result was a lively dialogue about how digital approaches can make medieval iconographic study more accessible to a diverse, global audience.

One of the first topics of discussion was the avenues by which viewers encounter medieval iconography in the twenty-first century. Anne Stanton, Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Missouri, raised the point that popular social media outlets and online databases are often the first portals through which many students gain access to medieval images and learn about subject matter in works of art. Many institutions have responded to this this fact by using social media platforms to broaden interest in iconography and connect users to works of art. The many vibrant examples of social media use in the field, ranging from museums to libraries, include the Getty, Dumbarton Oaks, and the British Library. Sabine Maffre, Curator of the Mandragore Database at the National Library of France, discussed developments at the library’s blog Gallica, which has been inviting professional bloggers to write posts about illuminations in order to diversify their audience and make their medieval image collections more visible.

Beyond questions of access, another change has occurred in the ways in which we think about iconography. Konstantina Karterouli, postdoctoral fellow and graduate of Harvard University, presented an Artificial Intelligence (AI) project that the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection is developing with the goal of teaching computers to recognize the different architectural elements of a medieval building. Commenting on the wider potential of this approach, Maffre also noted that the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) staff have been working toward implementing automatic recognition of manuscript illuminations through AI. A contrasting approach to iconography, presented by Isabelle Marchesin of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA) at the Sorbonne in Paris, faces head-on the problem of offering something that AI still cannot provide: interpretations of specialized content. The OMCI (Ontology of Medieval Christianity in Images) project, founded and developed by Marchesin, is based on the concept that, beyond narrative and portraits, Christian medieval images implicitly refer to another level of signification that is ontological and strongly connected in this case to theology as a holistic system of explanation of the world.

One important takeaway from the roundtable was the recognition that the role of the iconographer itself is changing. As Professor Marina Vicelja of the University of Rijeka emphasized, rather than requiring the solitary work so often undertaken in the past, it could and should be seen in light of collaborations, interdisciplinary research, and international networks. A starting point could be the implementation of cross-discoverable databases, shared standardized vocabularies, and the use of platforms like Biblissima, a digital library and widely interoperable data cluster designed to gather and give access to the main iconographic and textual databases. These ideas inspired discussion of the difficult balance between the strategies used by database specialists and the kinds of usability expected by twenty-first century researchers. Karterouli strongly emphasized the importance of standardization in these endeavors to help retrieve information, and Vicelja stressed the necessity of integrating metadata in order to avoid misunderstandings.

In the twenty-first century, we find ourselves at a crossroads between traditional methods of iconographic study and the implementation of pioneering technologies such as AI. The potential for interoperable platforms to enhance the research experience could answer new expectations with new possibilities. While it can be difficult to strike a balance between time-tested approaches and new ideas, the tension is proof that the study of iconography is very much alive and evolving. We hope that the Index roundtable at Kalamazoo was only the first word in a vibrant and expansive dialogue among an international community of creators and consumers of information about medieval iconography.