This blog post is the fifth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce Pamela Patton.

What is your background and specialization?

I’m a medievalist who studies the visual culture of the Iberian Peninsula, a focus that began at Tufts University when my advisor Madeline Caviness pointed me toward the Pamplona Bibles as a research topic. I was fascinated, and still am, by the complexity of medieval Iberian culture and its historiography—the questions are constantly evolving. The decision served me well: after doing grad degrees at Williams College and Boston University, I was offered a fellowship at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, which then evolved into a split curatorial and faculty position in “Spanish Art.” Although I shifted out of curatorial work after tenure, as a professor at SMU I was able to develop several courses on medieval Iberia as well as other aspects of the Middle Ages. Since coming to the Index in 2015, I’ve continued to research and occasionally teach medieval Iberian things, and I’m always happy to pitch in on cataloging works of art from Spain for the database. After 30+ years in the field, I do occasionally wonder if I should wander into some other part of the world, but then some great new Iberian question turns up, and back I go.

What research projects are you working on currently?

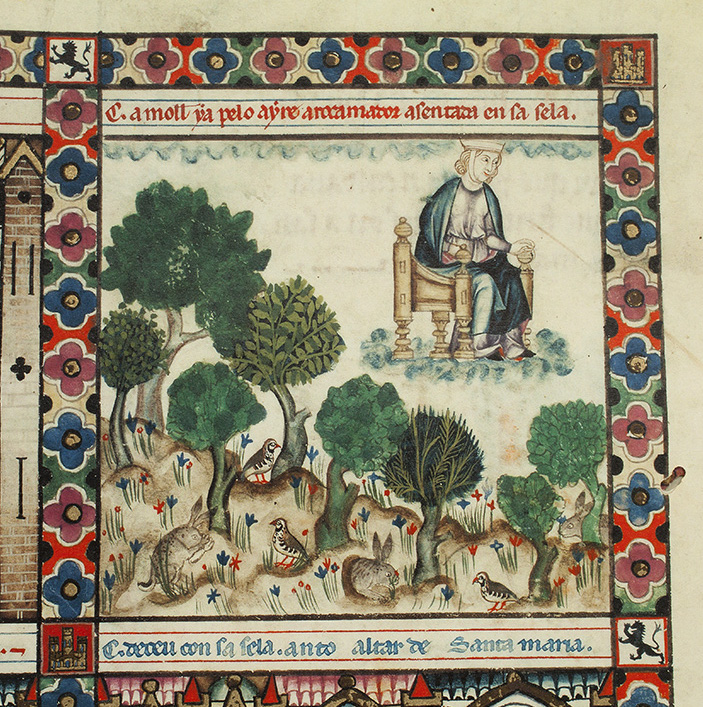

I’ve just wrapped up a project on how skin color and stereotype were used in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Iberia to signal racial, social, and cultural difference, and that’s inspired me to think further about the role of improvisation generally in Gothic manuscript illumination, specifically in the illustrated manuscripts of the Cantigas de Santa María, which were made for Alfonso X of Castile in the late thirteenth century. Illustrating the four hundred songs that were to be included in those two manuscripts must have been a massive task, and the artists met the challenge with some highly inventive iconography—giant silkworms, flying chairs, dancing pork chops, and the like. They must have had considerable latitude, in addition to a wonderful imagination!

What do you like best about working at Princeton?

Princeton does things for real. Very few universities so effectively hold teaching and research at their core, not to mention committing the resources that help them happen. As Index director, I especially appreciate the openness to new ideas, the support for scholarly initiatives, and the extraordinary research resources. These things don’t happen by themselves; they take investment at the highest level. On a more personal note, I’m grateful every day that when I go to work I have the opportunity to hear and share ideas with so many bright, thoughtful people, both in the Index and throughout campus, and in such a beautiful place. It’s a fine reason to get up in the morning.

What travel experience played a role in your becoming an art historian?

My mother had always wanted to travel, and when I was a child she and my father twice managed to put aside enough money to take the whole family to Europe. Remember Arthur Frommer’s Europe on $10 a Day? My mother really did that. I loved visiting all the art museums and historic sites, but I think reading The Hobbit on the train between cathedral towns in England was probably what made me a medievalist. The line between history and fantasy obviously was very blurry for me then, but somehow I became absolutely certain I wanted to learn more about this stuff. Corny, okay, but give me a break—I was eleven.

What do you like best about being back on campus in person?

People and books. I really missed the easy discourse that comes with sharing a coffee, talking over a research question, or listening to Q&A after a lecture. Ideas flow so much more freely when you’re in person and the moment has your full, active attention. And there is nothing more inspiring than walking into the library stacks to find the physical book you need: the excitement of spotting and opening it; the anticipation of what you’ll find in its pages; the serendipity of seeing what else is on that shelf. And the lights! I really like how the lights in Firestone brighten gradually when you walk into an individual aisle. It’s as if the light bulb that’s about to go off in your head is already going off all around you.

Coffee or tea?

Yes, please, all of it. I would drink coffee all day if I could, especially if it’s the cortados that I got hooked on during dissertation research in Spain. But to spare my co-workers a jittery colleague, in the afternoon I usually segue into tea, ideally a nice green jasmine.

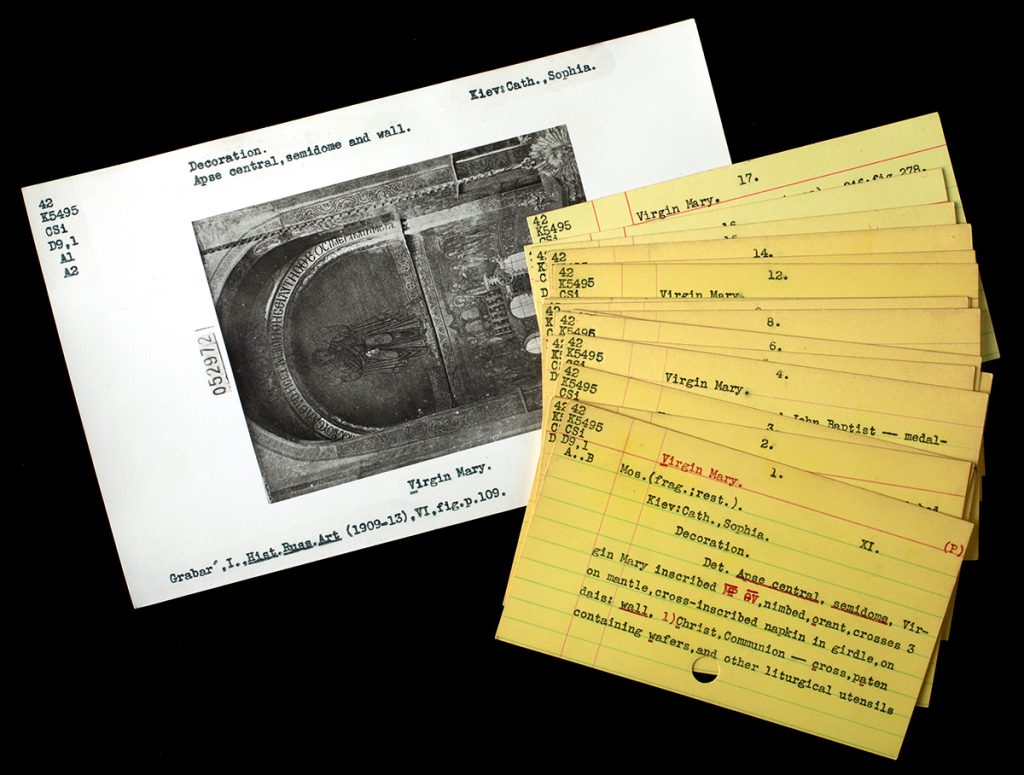

We are very pleased to announce that Prof. Julia Matveyeva will be joining the Index remotely in August to work on adding iconography from Ukraine’s medieval cultural heritage in the online database. Matveyeva will begin with St. Sophia in Kyiv, a UNESCO world heritage site and central medieval monument in the history of art. Legacy records of the mosaics of St. Sophia in Kyiv already exist in the print collection of the Index, as do those from Saint Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral and almost two dozen records of icons and other objects in Kyiv museums. However, scholars who are not able to travel to use the print Index on the Princeton campus have had no access to these images or their metadata, which moreover are in need of updating. By the end of the project in December, these works of art will be updated and incorporated into the online database, making them available for study by an international community of scholars, students, and lay learners.

Matveyeva is an Associate Professor at the department of Fine Arts and Design of the O. M. Beketov National University of Urban Economy in Kharkiv. Her research has been primarily focused on Byzantine iconography, especially textiles and embroidery, within the Empire and in the neighboring territories, including Kievan Rus’, Romania, Bulgaria, and Italy. Her book Decorative Fabrics in the Mosaics of Ravenna: Semantics and Cultural Context was published in 2020 and she is now working on a new project titled The Evolution of the image of the altar space: from liturgical fabrics to iconostasis in the 4th- 15th centuries. Subjects, semantics, iconography.This project was made possible by a Flash Grant from the Princeton University Humanities Council.

Please save the date for the next Index of Medieval Art conference, “Looking at Language,” on November 12, 2022. Assuming no major changes in university or government pandemic protocols, the conference will be hosted in person as well as live-streamed. It will feature eight medievalist scholars, in a wide range of specializations, who will address the many relationships between language and works of art, including the literal use and/or representation of language in creating a work; the linguistic traditions that surrounded its creation and reception, and the language now used to analyze and understand it. Speakers will include:

Ludovico Geymonat, Louisiana State University

Margaret Graves, Indiana University

Ruba Kana’an, University of Toronto

Sean Leatherbury, University College, Dublin

Sarit Shalev-Eyni , Hebrew University

Kathryn Starkey, Stanford University

Ben Tilghman, Washington College

Warren Woodfin, Queens College CUNY

The conference schedule, location details, and live stream registration link will be posted in September.

This blog post is the fourth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce Catherine Fernandez.

What is your background and specialization?

As a medieval art historian, I owe so much of my intellectual formation to the universities where I earned my degrees. Can I use this space to give a shout-out to all the medievalists—both past and present—at Florida State University and Emory University? My academic journey, so to speak, began at FSU with two BAs, one in English Literature and one in Art History. I earned my PhD in Art History at Emory and then headed up the east coast to join the Index research staff immediately after graduation. My current research interests center on medieval treasuries and French Romanesque art, but I am happy to get my thousand-year medieval “fix” through various Index projects. Based on cataloguing or classroom instruction needs, I might be simultaneously working on an Ottonian manuscript, a late-antique sarcophagus, or Gothic archivolts; it’s an embarrassment of riches.

What research projects are you working on currently?

At the Index, I happily embrace a wide range of topics, but I am particularly thrilled to have worked with our IT guru Jon Niola in the development of a field within individual records that “maps” iconographic programs within medieval buildings and other structures. By highlighting the placement of in-situ works of art, the “Location in Structure” field can only amplify our understanding of medieval iconography’s spatial dimension. With regard to my own research, I am currently working on my book project, entitled Charlemagne’s Pectoral: The Presence of Carolingian Memory at Saint-Sernin of Toulouse. This monograph seeks to reintegrate a group of extraordinary treasury objects associated with the emperor Charlemagne within the liturgical space of the famous Romanesque shrine.

What do you like best about working at Princeton?

It remains an absolute pleasure to work with so many wonderful medievalists—both members of the local community and visiting scholars—and participate in the “Life of the Mind” on campus.

What travel experience played a role in your becoming an art historian?

I consider myself fortunate to have had an upbringing that included extensive global travel. Over the course of my childhood, my family visited countless monuments, museums, galleries, and archaeological sites around the world, and any number of these places could have infected me with the “art history bug.” But humor me, if you will, when I give credit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and E.L. Konigsburg’s novel From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. I mean, what art historian hasn’t fantasized about hiding out at the Met like the novel’s two child protagonists?

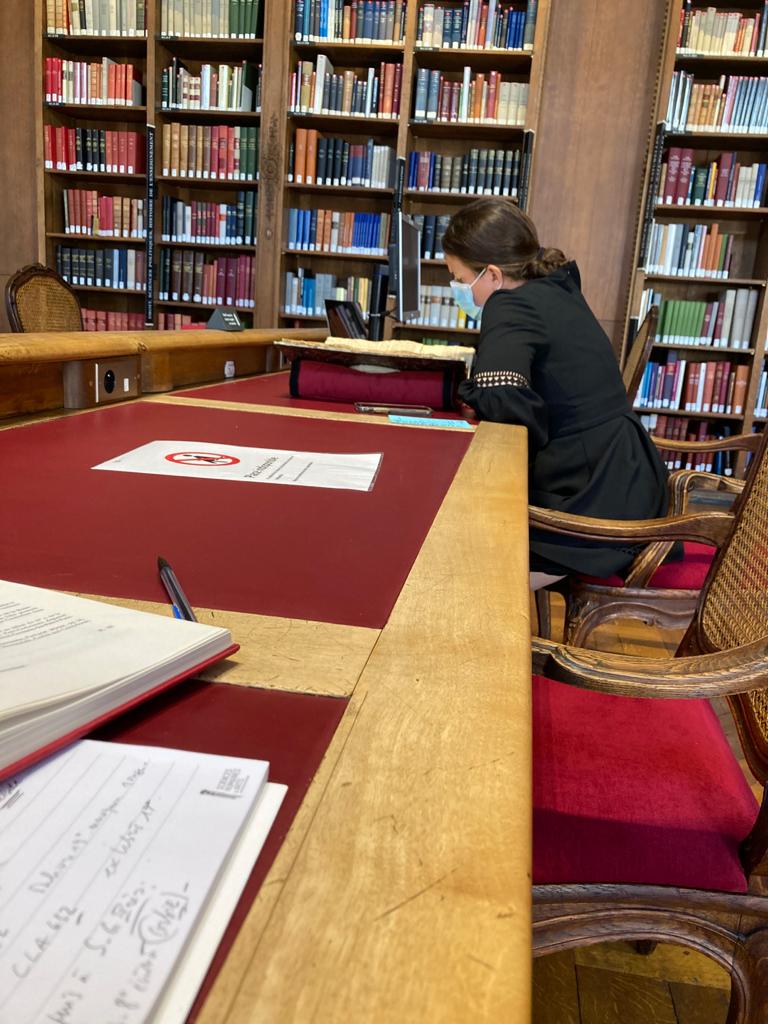

What do you like best about being back on campus in person?

Close access to actual libraries and actual human beings, as I am rather fond of both.

Coffee or Tea?

Red Bull. Blueberry flavored. What? Was I supposed to wax poetic about some kind of refined oolong?

The Index of Medieval Art invites applications for a four-month, remote, part-time research position to assist in incorporating key mosaics and paintings of medieval Kyiv into the Index database. This position is made possible by a 2022 Flash Grant from the Princeton University Humanities Council and consists of a $5,000 honorarium to be directed to the scholar.

The successful applicant should have relevant training in art history, preferably with a medievalist background, and should hold a doctorate or have completed all but the dissertation. Applicants may be of any nationality, but preference will be given to a scholar whose work has been disrupted by the crisis in Ukraine. A reading knowledge of Russian and Ukrainian is preferable.

The work position will require roughly two days a week of remote work over a four-month period, beginning in summer of 2022. The successful applicant will work with the Index research staff to catalogue Ukrainian monuments, beginning with the cathedral of St. Sophia in Kyiv. They will be trained in Index norms in cataloging the monumental structure, describing the iconography of its paintings and mosaics, transcribing inscriptions, and adding bibliographic citations, Index subjects, and other metadata. Staff guidance and scans of the relevant print material will be provided. The timeline for this work is somewhat flexible but must be completed by the end of the funded period, December 31, 2022.

To apply, please send a CV and letter of interest to marossi@princeton.edu and ppatton@princeton.edu by June 1, 2022

NB: This satirical post was shared in celebration of April Fool’s Day 2022.

Many here in New Jersey are admirers of Nora, the Piano Playing Cat, the Camden kitty who since 2007 has wowed music lovers worldwide with her talent at the keyboard. Her fame even inspired the Lithuanian conductor Mindaugas M. Piečaitis to compose her a “Catcerto.” If you haven’t ever heard this piece, by the way, it’s well worth a listen.

But are musical moggies really a modern phenomenon? Evidence unearthed by researchers at Princeton University’s Index of Medieval Art suggests otherwise. Manuscript illuminations from late medieval Europe clearly depict cats performing on a variety of musical instruments, from the organ and tabor to the vielle and more. Here we present a preview of findings from this pathbreaking research project, soon to appear as an article in the interdisciplinary medieval studies journal Scientia de animalibus.

Musical training of felines often began at the keyboard, allowing teachers to capitalize on cats’ natural impulse to bat at a target with their paws. Meticulous application of a featherstick to each key to be struck, along with the copious provision of treats, encouraged both musical precision and a vigorous technique on both portative and positive organs.

Further mastery of percussion came with training in the tabor, a small hand- (or paw-) held drum that is played with a stick. A small strap was used to affix the drum to the cat’s left paw while it impaled the stick with its claws. Although this technique must have been difficult to learn, the surviving images suggest that some cats mastered it so well that they could stand on their hind legs while playing.

Those cats with sufficient coordination and ambition could next be moved on to bowed instruments like the vielle, shown here. In addition to requiring vertical balance, this instrument demanded both toe dexterity and a highly refined ear, the latter fortunately not a problem for these aurally acute ailurids.

Only those cats with the highest musical ability could advance to learning the bagpipes because of the precision needed to coordinate breathing, elbow pressure, and the placement of toe pads. Among the few feline masters of this instrument was a white monastic cat named Pangur Bán, whose signature “Katzenellenbogen” performance technique is still used by pipers today. Pangur was a true polymath who was also commemorated in verse for his “joyous with speedy going” after mice in his home abbey near Reichenau. Index researchers believe that the image above may portray Pangur himself, based on his obvious mastery of tongue and paw position.

We at the Index hope that you’ve enjoyed this foray into our research on medieval feline musicians, who set the stage for Nora and the rest of today’s musical cat performers while also launching your April Fool’s Day 2022 on a truly harmonious note.

This post is the third in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce Henry D. Schilb.

What is your background and specialization?

Maybe I ought to have been a musicologist. Among other things that I almost got away with in my life, I once wrote, produced, and hosted a radio series about twentieth-century music. That was during the fifteen years that I worked as an announcer at a couple different public radio stations (among many other brutally low-paying jobs I’ve held down, often two or more at a time). In those heady days, I sneaked works by Ruth Crawford Seeger, Harry Partch, Iannis Xenakis, György Ligeti, Pierre Boulez, George Walker, and even James Tenney onto the airwaves, no mean feat at that time. Oh, how invigorating were the listener complaints! No composer younger than Brahms was safe from the acrid contempt of the average public radio listener, but I still especially cherish being told by one listener that I myself was what was wrong with the world—and this was in the early ’90s, so the listener who lodged that complaint had no idea what was coming!

Although I always fear that too many minds nestled between incurious ears remain impervious to the pleasures of new music, or simply unaware of them, let me hope that there are some—among those who have survived more than twenty percent of the twenty-first century with a spirit of adventure intact—who will forgive me for seizing this moment to direct their attention to the music of George Lewis, Chaya Czernowin, Unsuk Chin, Rebecca Saunders, and Olga Neuwirth. I could go on, but that’s a good start. You can thank me later.

But, for some reason, I’m an art historian now. I earned my PhD at Indiana University in 2009, and I specialize in late-Byzantine art, and embroidered liturgical textiles in particular. Yeah, I’m a real hoot at neighborhood parties.

What research projects are you working on currently?

Quite by mistake, I find myself the resident geographer at the Index of Medieval Art. Maybe I spend too many of my waking hours thinking about how to deal with location information in our database, but I rather like that part of my job. In my own research, however, I still focus on embroidered veils. Back in November, I presented a paper at the Index’s conference on “Fragments, Art, and Meaning in the Middle Ages.” I discussed, among other objects, a textile in the Princeton University Art Museum. I’m also optimistically planning a trip to Canterbury Cathedral to visit a post-Byzantine textile that has a very strange history indeed. Remind me to tell you about it sometime.

What do you like best about working at Princeton?

Even after ten years at Princeton, I still think it’s pretty cool to work at the same university where Roger Sessions taught for many years. (Yes, he’s another composer whose music I love.) Also, I like to go for a long run after work, down to the towpath, along the canal, and then back up through campus, through the majestic arches and under the leafy canopy. Like me, the campus is at its best in October.

What do you like best about being back on campus in person?

Although I thrived while working from home during the pandemic, and my productivity really went through the roof, I suppose that the return to campus back in September was inevitable. As for what I like best about The Return, I’ll simply refer you to my comments above regarding running through campus. I have to say, however, that the experience now can be rather spoiled by all the construction…and those danged scooters.

What travel experience played a role in your becoming an art historian?

My honest answer to this question is boring. It’s also probably cheating. It was not a literal journey, you see, but a slide show in the first art history course that I took in college in 1984. So, the first time I looked closely at a picture of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul—that’s what’s really to blame for my being at the Index of Medieval Art today.

But I’ve been traveling all my life. I said my first word at Expo 67 in Montreal. Well, two words, technically, I guess. What I said was “egg roll.” And I meant it.

Of course, destiny-shaping travel needn’t take you any great distance. When I was a kid in Lockport, Illinois in the ’70s, every trip to the Field Museum in Chicago felt like a profoundly life-altering experience. I still keep a pair of Mold-A-Rama dinosaurs in my office at the Index.

Mold-A-Rama? Google it.

When I lived in England in the late ’80s, I used to love to take a drive to Little Gidding, just to hang out, wander around, listen to the wind, ponder the landscape, and to think about poetry, music, history, and…just to think. I was always surprised that I never encountered another visitor there. Every trip to Little Gidding was very different from the Bloomsday I spent in Dublin, which must have been in ’89. You couldn’t sneeze without jostling some other tweedy nerd trying to wash down a gorgonzola sandwich with a glass of burgundy.

On research trips, I still always try to do something just for fun, something that has nothing to do with my research—even nothing to do with art history—but everything to do with who I am, so one of my favorite travel experiences was a visit in 2005 to Sighișoara, Romania, the birthplace of Vlad the Impaler. Good times!

Coffee or tea?

Yes, please.

This blog post is the second in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce Jessica Savage.

What is your background and specialization?

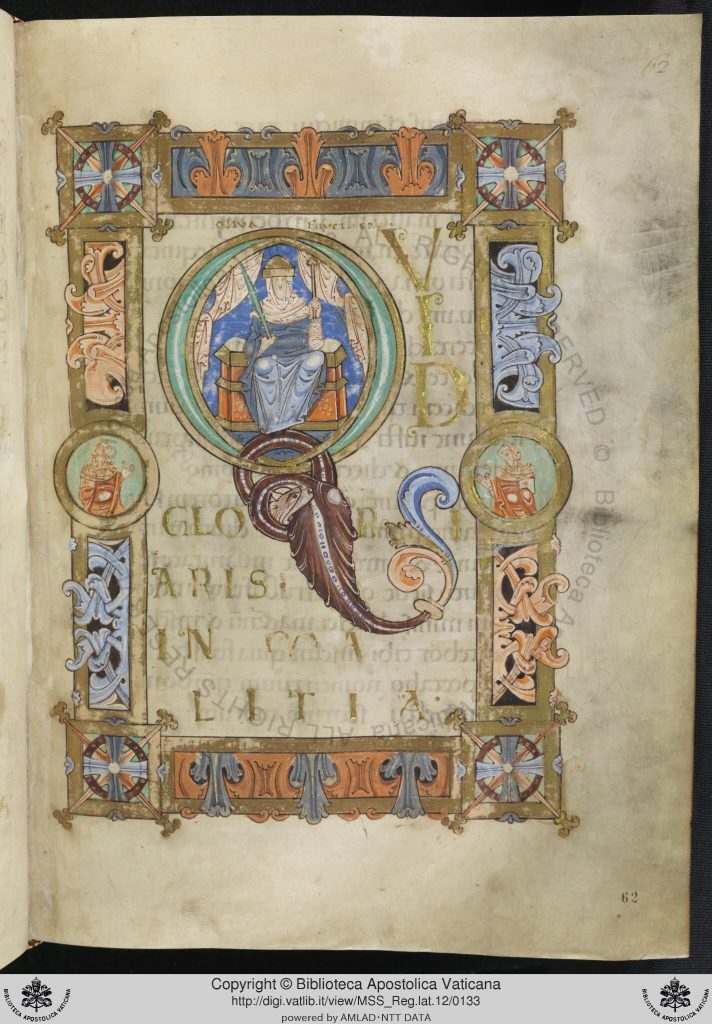

I am an Art History Specialist and Index cataloger of Western medieval art, specializing in the art of the medieval book in the later Middle Ages. My research focuses on topics of allegory, gender and personification, and text/image relationships, especially the deep-rooted iconography of personified virtues as they appear in the Psalms. My background is in studio art, and I initially trained as a painter and printmaker at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. My first art history survey course at Pratt, now twenty years ago, commenced with a discussion of the Venus of Willendorf and you could say I haven’t looked back since! I completed my postgraduate training at Christie’s Education in London and earned my MLitt degree in the History of Art from the University of Glasgow. Here, I wrote my thesis on the iconography of local popular saints depicted on pilgrim’s souvenirs in late medieval England. In 2010, after briefly working as a manuscript specialist for an auction house in New York, I joined the Index to research manuscripts for the joint digitization project undertaken by the Index and the Morgan Library & Museum. This was an enriching start to my Index career, which allowed me great digital access to remarkable manuscripts and their iconography. Later, I pursued an education in library and information science at Rutgers and earned my MLIS degree with a focus on archives.

What research projects are you working on currently?

For the Index, I continue to catalogue illuminations of late medieval manuscripts photographed by James Marrow, Princeton History of Art Professor Emeritus, as well as contribute research for items in the Index card catalog not yet entered into the database, focusing on manuscripts and ivory objects. I am working on a few independent research projects for various conferences and publications. My first project, in collaboration with scholars at the University of Tübingen, is an article on the almsgiving Charity figure, wearing the olive-tree crown, in the forthcoming volume “Personifications in Text and Image.” This study looks at the expression of this charitable personification in an early medieval illuminated Psalters and considers their representational potential and role in conveying meaning. A second project considers a little studied illuminated Prayer Book made in Prague for King George of Poděbrady (r. 1458–1471). The manuscript was made and presented to the king in the year 1466 and is now housed in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York as MS. M.921. This research focuses on the visual relationships within the small cycle of devotional illuminations produced at the fifteenth-century Bohemian court under queen Joanna’s patronage. In early May, I’ll be presenting in the sponsored session of the Society for Emblem Studies at the virtual Kalamazoo conference with new work on the medieval sources of emblematic images inscribed with psalm verse and finding their subject standards.

What do you like best about working at Princeton?

I like best that my days at the Index are full and interesting. Some days I spend looking at an object in our subject card catalog and photographic archive, making trips to the library to check bibliographic references, or answering a research question. Other days I might be editing images, or cleaning data so it is more easily searched in the database. The angles to searching Index information are adaptive, and it’s rewarding to find a new route to discover parts of the collection and share these finds with researchers and colleagues. Moreover, Princeton fosters a supportive environment for research and learning with lectures, workshops, and conferences in any number of topics.

What travel experience played a role in your becoming an art historian?

There were several travels as a graduate student in the UK that played a role. However, one unexpected experience was more recent and closer to home. A few months ago, I rediscovered a statue of the Czech theologian, Church reformer, and martyr Jan Hus (1369–1415) in my hometown on Long Island. The statue of Hus, holding a chalice (the symbol of Utraquist belief in full communion), was erected in Bohemia, New York in 1893. It is known to be one of only two statues of Jan Hus in the United States and it predates the establishment of the Hus memorial in Prague’s Old Town Square by twenty-two years. I am currently researching the 1466 Prayer Book of George of Poděbrady (Morgan Library & Museum, MS. M.921), belonging to George, the Utraquist king of Bohemia, who ruled in the turbulent decades after Jan Hus’s death in 1415. I found it a happy occasion to pay a visit to the important local statue!

What do you like best about being back on campus in person?

After a long separation from the archive and face-to-face conversation with colleagues, it’s wonderful to be back on campus and in the vibrancy of the Princeton community again. What I like best about working at the Index is the comradery over our projects and the rigor of the schedule, which makes every day feel like you’re adding to the pot of progress. It’s also been great settling into our new temporary space in Green Hall and being close to Firestone Library.

Coffee or tea?

I drink tea most days and will have coffee, especially an espresso, on occasion. My regular teas are smoky Earl Grey, oolong tea, and an aged black tea from China called Pu-erh. I believe you also can’t go wrong with the perfect cuppa and enjoy the Yorkshire Gold breakfast variety for that. Teas are wonderful from the blending to the infusion process. I’d almost say, it’s an art!

As many Index subscribers know, reducing subscription fees for the Index of Medieval Art database has been an institutional priority since the launch of its new digital platform in 2017. Because the Index budget, which supports the work of seven full-time staff members as well as a program of respected publications and conferences, relies in part on subscription revenue, such reductions have had to be gradual. But they have continued, and as we approach the five-year mark, we’re very pleased to announce that our institutional subscription fee for the coming fiscal year will be $500 per year, one third of the $1500 per annum paid by institutions when the reductions began.

We recognize that access to online resources has become increasingly important as a global pandemic and ongoing budget pressures continue to reshape teaching, learning, and research in higher education. We hope that this further fee reduction will help more institutions choose to make the Index available to their scholarly communities. Should you wish to discuss a free trial or subscription to the Index, please contact office coordinator Fiona Barrett (fionab@princeton.edu).

On January 13-15, the Index will co-host the hybrid conference “Power, Patronage, and Production: Book Arts from Central Europe (ca. 800-1500) in American Collections” in conjunction with the exhibition “Imperial Splendor: The Art of the Book in the Holy Roman Empire, 800-1500” at the Morgan Library & Museum. The exhibition presents material that has never before been gathered together, treating topics including visual rhetorics of power in book media, the production and patronage of manuscripts, the relationship between vernacular and Classical languages, and the position of imperial cities in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The conference expands this with papers on such themes as the networked relationships among centers of production; the representation of male and female patrons; early print culture; and the role of books in key developments for liturgy, private devotion, chronicle writing, and the law. A schedule of speakers (including Index Specialist Jessica Savage) is available here.

The conference will run in hybrid form. In-person attendance is contingent on space; due to current campus public health policy, registration will be limited to Princeton University ID holders and visitors sponsored by the Department of Art & Archaeology. We cordially invite attendance on Zoom by all interested in the conference proceedings.

The conference is co-sponsored with the Department of Art & Archaeology, the Center for Culture, Society and Religion, the Program in Medieval Studies, the German Department, Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS), Humanities Council, Delaware Valley Medieval Association and The Morgan Library and Museum. We hope many of you can join us for this event.