The Index will be represented at two events at the Medieval Congress at Kalamazoo this year. First is a joint reception with the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence at 5:15 pm on Friday, May 13, in Bernhard 208. Second will be two sessions, titled “Pardon Our Dust: Reassessing Iconography at the Index of Christian Art,” organized and chaired by Index researchers Catherine Fernandez and Henry Schilb, on Sunday from 8:30 to noon in 1145 Schneider Hall. We hope to see many friends there!

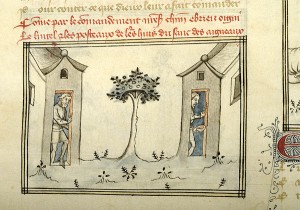

Detail of Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent. Old Testament Picture Book. French, c. 1250. Morgan Library, M.638, fol. 8r

Nine times Moses went to the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II to demand freedom for the Israelites in captivity, saying “Let my people go.” Each time Moses and his brother Aaron were sent a way, an episode classified by the Index as, Moses and Aaron: driven from Pharaoh’s Presence. Despite these increasingly tense exchanges, and then a marvelous act that changed Aaron’s rod into a serpent before the Pharaoh’s court (Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent), Ramses still refused to release the Israelites from slavery.

What followed was the foretold wrath of God enacted as ten crippling plagues on the Egyptians. In the first wave of calamities, there were plagues of blood, frogs, gnats, and lice that polluted the air and water. The second wave, brought plagues of flies, diseased livestock, and boils. Then came hail, locusts, and darkness that fell on Egypt for three days. The tenth and final plague, the “Plague of the Firstborn,” claimed the lives of the eldest children in all Egyptian families. The Index of Christian Art classifies the subjects of the Exodus plagues under the major figure of Moses:

Moses: Plagues of Flies, Frogs, Locusts, Hail and Pestilence. Stuttgart Psalter, c. 820-830. Stuttgart Landesbibliothek, Bibl.fol.23, fol. 93r. Photograph by Gabriel Millet.

(Exodus 9:6-7)

The final plague is described in several phases throughout the books of Exodus (11:4-8; 12:1-13, 21-23, 29-30). Moses first warns of its coming to the embattled Ramses, but his warning is dismissed.

Facing the impending deadly plague, Moses instructs the Israelites to make a sacrificial offering to God, and to use the blood of the animal – a male yearling – to mark the doorposts and lintels of their homes. Moses explains to them that marking their homes this way will spare their firstborn children from the “death angel,” saying he “will pass over the door.” (Exodus 12:23).

Moses: Plague of Firstborn. Two Israelites marking the doorposts and lintels of their homes with the blood of the sacrificial lamb. History Bible, Paris, c. 1390. Morgan Library, M.526, fol. 14v

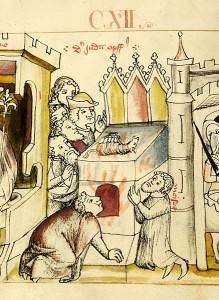

Detail of Moses: Passover. Israelites cooking the sacrificial lamb under the inscription “Die Juden Opffer.” Historien Bibel, Swabia, late 14c. Morgan Library, M.268, fol. 7v

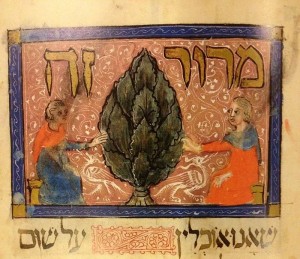

Following this, the Israelites were delivered from bondage and departed from Egypt. The Exodus is remembered at the feast of Passover – the Hebrew feast of Pesach – with special instructions for preparing, eating, and storing traditional, often symbolic food. While Passover traditions have varied over time and from one region to another, it is generally a family holiday in which the meal is accompanied by readings, songs, and traditional rituals designed to remind the celebrants of the Exodus story and the hopes for a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. The order of the seder, or Passover meal, is set out in a book known as the Haggadah, which was sometimes richly illuminated in the Middle Ages, as shown here in the Sarajevo Haggadah, originating in Barcelona in the middle of the 14th century. Well-known related manuscripts to this Haggadah include the Rylands Haggadah and the Simeon Haggadah. The Index classifies subjects depicting the original Passover feast as Moses: Passover, Moses: Passover proclaimed, and Moses: Law, Feast of Passover and with a general heading for Scene: Passover.

Bitter herb or “maror” in the Sarajevo Haggadah. Barcelona, c. 1350. Sarajevo, National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photograph Wikimedia Commons.

The middle of April strikes dread (or joy) in the hearts of millions of tax filers. Since 1955, April 15 has typically marked the end of the tax season in the continental US. This year, however, filers have received a three-day reprieve to accommodate Emancipation Day in Washington D.C, which is observed on the weekday closest to April 16 when it falls on a weekend.

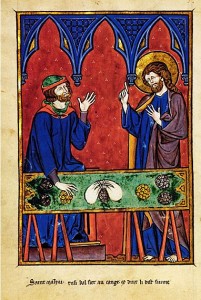

Saint Matthew is among the best-known tax collectors in the history of Christian art. According to the gospel accounts, Jesus encountered Levi (Matthew’s name before his conversion) in the custom house of Capernaum on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. Jesus said to him, “Follow me,” and Matthew obeyed.

A remarkable depiction of Christ calling Matthew appears in the Picture Book of Madame Marie, a thirteenth–century French devotional manuscript now at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. The scene takes place beneath sharply-cusped arches and against a fiery background. Wearing a brilliant blue garment and purple cloak, Christ addresses Matthew, whose money table has been dramatically tilted to reveal neat piles of gold and silver coins. Thematically related is a fifth-century gold solidus of Pulcheria with the empress wearing an elaborate coiffure and lavish jewels, a macabre Dance of Death featuring a money-changer from a fifteenth century French Book of Hours, and a regal image of the Queen of Coins on a fifteenth-century Italian tarot card.

May the rocks in your field turn to gold!

Heartfelt thanks to the over 150 people who took our online survey this past month. Your thoughtful, detailed responses will be central to our plans for the coming year. They confirmed many concerns already on the mind of Index staff, especially concerning the difficulties of navigating our current database. They resolved a few hot office debates over how researchers approach the system (Team “Keyword Search” routed Team “Browse List,” 93-7, while “Search by Subject” ran away with “Initial Search Field,” earning 87% of responses). They also offered high marks for the accuracy of our data and the quality of our programs and publications. Most appreciated of all, however, were your concrete, insightful suggestions about how the new database could be designed so as to perform most effectively for an evolving scholarly community.

Heartfelt thanks to the over 150 people who took our online survey this past month. Your thoughtful, detailed responses will be central to our plans for the coming year. They confirmed many concerns already on the mind of Index staff, especially concerning the difficulties of navigating our current database. They resolved a few hot office debates over how researchers approach the system (Team “Keyword Search” routed Team “Browse List,” 93-7, while “Search by Subject” ran away with “Initial Search Field,” earning 87% of responses). They also offered high marks for the accuracy of our data and the quality of our programs and publications. Most appreciated of all, however, were your concrete, insightful suggestions about how the new database could be designed so as to perform most effectively for an evolving scholarly community.

Three issues emerged repeatedly in the survey results. First was navigation: many researchers reported difficulty using the online database because of outdated or unwieldy design, unfamiliar terminology, and a lack of research guidelines. Close behind this was cost: past subscription fees for the Index have been high enough to make access difficult for smaller institutions and individuals. Finally, many researchers expressed concern about access to and quality of images: not only did past policies at the Index restrict many images from view by remote users, but the quality of our older images (some nearly a century old) can be quite low.

We hear you, and we are happy to say that most of these issues should be mitigated as we move to a new database design over the next two years. We are currently engaged in selecting a vendor to create the new system, which will be more intuitive, researcher-oriented, and image-centered than the original 25-year-old design. We also expect it to be more efficient, allowing us to migrate existing data and integrate new material, including improved images, with greater speed and effectiveness, while nationally changing practices surrounding copyright and fair use will allow us to make more of those images available universally. Finally, once a vendor is selected and the database is in design, we will address the question of subscription costs with our advisory committee, with the goal of offering more affordable access to the database for both institutions and individuals, including independent scholars and students.

We look forward to sharing news of all the changes to come at the Index as we approach our 100th year, and as always, we look forward to hearing from you when our resources or research staff can be of help to your work.

“And when he was come into Jerusalem, the whole city was moved, saying: Who is this? And the people said: This is Jesus the prophet, from Nazareth of Galilee.” (Matthew 21:10-11)

Celebrated seven days before Easter Sunday, Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Passion Week and commemorates Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The episode, which appears in the four canonical gospels, describes the multitudes gathering at the gates of Jerusalem to welcome Jesus, laying their cloaks and branches on the ground in recognition of his status as the Messiah.

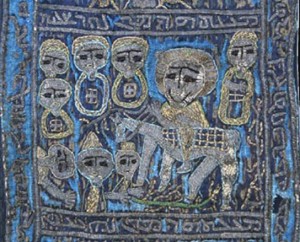

The earliest extant pictorial representations of the Entry into Jerusalem date to the fourth century, and the subject was popular across media throughout the Middle Ages. A highly compressed version of the episode appears on a fourteenth-century ivory diptych from the Abbey of Muri, Switzerland, which is decorated with Passion scenes. The right side of one of the leaves portrays a single disciple trailing the mounted Christ blessing two figures, who serve as shorthand for the multitudes. Equally schematic is the Entry into Jerusalem on the batrashil of bishop Athanasius Abraham Yaghmur of Nebek, produced in Syria in the fourteenth century. This long, embroidered stole shows three figures placing a palm branch before Christ, riding on an ass and attended by five disciples.

The lintel from the main portal of the twelfth-century church of San Leonardo al Frigido in Italy presents a more expansive version of the scene by illustrating all twelve disciples, their open mouths perhaps indicative of speech, and three small figures perched in a tree on the right-hand side of the composition. The last detail, common in depictions of the subject, relates to the prophecy of Zechariah, which describes children breaking branches from an olive tree and following the crowd into Jerusalem.

The model during Lent, the forty days of reflection and restraint before Easter, is Christ in the desert overcoming temptation. According to the Gospel writers Matthew, Mark, and Luke, Christ wandered alone in the Judean desert for forty days immediately following his baptism and before starting his public ministry. Satan first tempted Christ in the desert to turn stones into bread. Christ responded by quoting Deuteronomy 8:3, “It is written, man shall not live by bread alone…”. The Gospels describe two other attempts of temptation to win over both Christ’s pride and power. On the second temptation and with a dramatic setting change, Satan tested Christ to act independently from God and use his divine powers to jump from the height of the temple in Jerusalem – Christ firmly refused. Finally, Satan made a grand offer to Christ; to bask in the glory of all the kingdoms of the world if he would give up his mission and be partners with Satan, to which Christ replied, “Get thee hence.”

By the time of Gregory the Great, Pope from 590-604 CE, medieval Christians were expected to observe Lent by emulating these desert trials of Christ by fasting from animal products, remaining diligent in prayer, and giving alms to the poor. Typically, one meal per day was consumed during Lent; save the worship day of Sunday, observers were to resist all carnal attractions. The strict prohibitions during Lent required endurance from believers and tested their own degree of devotion.

The Index classifies the Temptation episodes in three major divisions according to the number of times the devil tried to seduce Christ. Currently, the database records the most scenes for “Christ: Temptation, 1st,” the temptation for hunger, and works of art are mostly executed in manuscript illumination, but also stained glass, fresco, and sculpture, as shown. There is also a general subject category for “Christ: Temptation” which is used to describe scenes where Christ and Satan are facing each other in an unknown part of the narrative or when all three Temptations are depicted in one scene as in the south vault mosaic at San Marco in Venice . “Christ: in Wilderness” is often a subsequent subject heading applied to the Temptation scenes as well as, “Christ: ministered to by Angels.” The latter records a specific part in the narrative when Christ is kept alive in the desert by angels following the departure of the devil. Lent, coming from the Old English word “lengthening,” is the transitional time in the church calendar and for the seasons.

This year, the vernal equinox in the northern hemisphere falls on Sunday, March 20, marking the moment when the sun shines directly on the equator and the length of day and night are nearly equal. In anticipation of the change of season, The Index of Christian Art presents images thematically related to spring. First, a fifth-century mosaic from the synagogue in Zippori, an abandoned Roman-era town in central Galilee, depicts a personification of spring, identified by Greek and Hebrew inscriptions. Portrayed with roses in her hair, the bust-length figure is flanked by a blossoming branch and a bowl of flowers (on the left) and a basket of flowers and two lilies (on the right).

Second, a personification of March, labelled MARCIUS, graces a Catalonian textile from the late-eleventh or early-twelfth century. The figure appears to be chasing a stork (CICONIA), known as a harbinger of spring because of its migratory patterns. The figure holds a serpent, described in medieval bestiaries as an enemy of the stork, and a frog, perhaps a reference to the rainy season. Above is a personification of the north wind (FRIGUS), as well as a crescent moon and blazing sun. Last, a thirteenth-century Flemish Psalter depicts a figure pruning a stylized tree, an agricultural labor closely associated with the month of March.

As you may know, the Index of Christian Art is in the midst of a major and long-awaited redesign aimed at making our online database more flexible, accessible, and user-friendly. Please help us by taking a very brief (5-10 minutes) survey about your use of the current database. Your responses will help refine the new design with our researchers’ needs in mind. You can access the link here.

All responses will remain anonymous, and all will be valuable in helping us to design a new database that will better serve you and all researchers whose work concerns the history and signification of images in the Middle Ages.

Thank you very much for your support of our work.

Celebrated annually on February 14 as a day for courtship and romance, Valentine’s Day began as a liturgical celebration in honor of one or more Early Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The Roman Martyrology mentions two Valentines, both of whom were decapitated on the ancient Via Flaminia, the main artery connecting the city of Rome to the Adriatic Sea. One Valentine died in Rome and seems to have been a priest. The other, who may have been a bishop, was martyred approximately 60 miles away at Interamna (modern Terni).

The earliest extant connection between Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (1383): “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” February 14 was associated with courtly love as early as 1400, in a charter ostensibly issued by Charles VI of France (d. 1422). The text describes the festivities of the royal court, which included love poetry competitions, dancing, jousting, and a feast. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm evidence linking Valentine’s Day with the ancient Roman Lupercalia, a pastoral festival observed from February 13 through 15 to purify the city of Rome and to promote health and fertility.

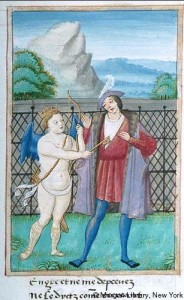

The Index of Christian Art is delighted to present four images thematically associated with Valentine’s Day. First, the nimbed Valentine of Rome is represented with the sword of his martyrdom in the fifteenth-century Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Morgan Library, M.917 and M.945). Second, a sixteenth-century Roman de la Rose contains a charming depiction of the God of Love locking the Lover’s heart with a giant key (Morgan Library, M.948). Third, a fourteenth-century ivory box cover of Parisian origin shows women defending the castle of love, a popular subject in late medieval courtly circles. The winged god of love at the top of the roundel prepares to launch his arrow, while women throw flowers at the attacking knights. Last, a sixteenth-century drawing from an Arma Christi and Prayers (Princeton University Library, Taylor 17), which portrays Christ’s heart with three blossoming flowers, is inscribed pyte, love, and charyte.

“Plus Ça Change…? The Lives and Afterlives of Medieval Iconography” takes place on April 29 at the Index of Christian Art. Presentations include:

“Rejection, Distortion and Destruction at Santa Maria in Trastevere.”

Dale Kinney, Professor of History of Art Emeritus, Bryn Mawr College

“The Archaeology of Carolingian Memory at Saint-Sernin of Toulouse.”

Catherine Fernandez, Research Scholar, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

“How Reliquaries Resist Iconographic Classification But Still Have Meaning”

Cynthia Hahn, Professor, Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center

“Signatures and Traces in the Art of al-Andalus.”

D. Fairchild Ruggles, Professor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

“Debating the Transfiguration In Fourteenth-Century Byzantium; or Why There Is No Hesychastic Art.”

Charles Barber, Professor, Princeton University

“The Frailty of Eyes.”

Kirk Ambrose, Professor and Chair, University of Colorado, Boulder

“Figuring Absence: Iconography and the Failure of Representation.”

Elina Gertsman, Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University

“The Work of Gothic Sculpture in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”

Jacqueline Jung, Associate Professor, Yale University

Generously co-sponsored by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, Princeton Medieval Studies, Princeton Art & Archaeology, and the Steward Fund in the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University. We look forward to seeing you!