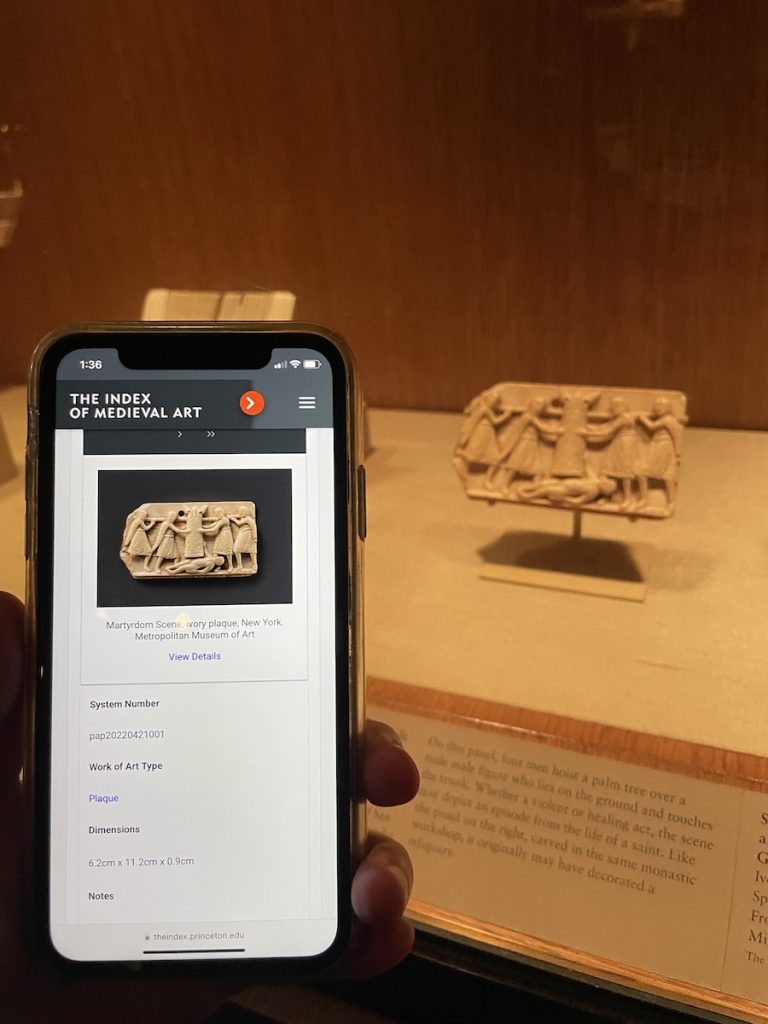

This summer the Index of Medieval Art achieved a milestone in our cataloging mission: the completion of all ivory objects in our print photo archive. In all, more than three thousand objects from the Index’s card catalog have been added to the Index database, significantly enhancing the online collection and establishing the Index as a more vital resource for the study of medieval ivories. The new records include chess pieces, croziers, caskets, combs, retables, diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs, knife handles, mirror cases, oliphants, pyxides, statuettes, and much more! Many of the works of art date to the Gothic period, but late antique, early medieval, Romanesque, Carolingian, Siculo-Arabic, and Byzantine works are also well represented. The materials and techniques categorized as “ivory” were also surprisingly diverse, including carvings in walrus tusk, also known as morse, as well as in horn, bone, antler, and even a ceremonial staff made from narwhal tusk.1

The ivory cataloging project was begun shortly after staff returned to in-person work during the later stages of the pandemic. Index research staff worked from inventories of the photo files made by former student assistant Michele Mesi in 2019.2 Many of the photo files dated from the 1930s to 1950s, and they usually provided a subject and photograph with a bibliographic reference, though sometimes they included much less! Working from the clues left by earlier generations of Indexers, the current crew shared key publications and relied when possible on databases, such as the Courtauld Institute’s Gothic Ivories Project, to work through the records alphabetically by location and collection.3

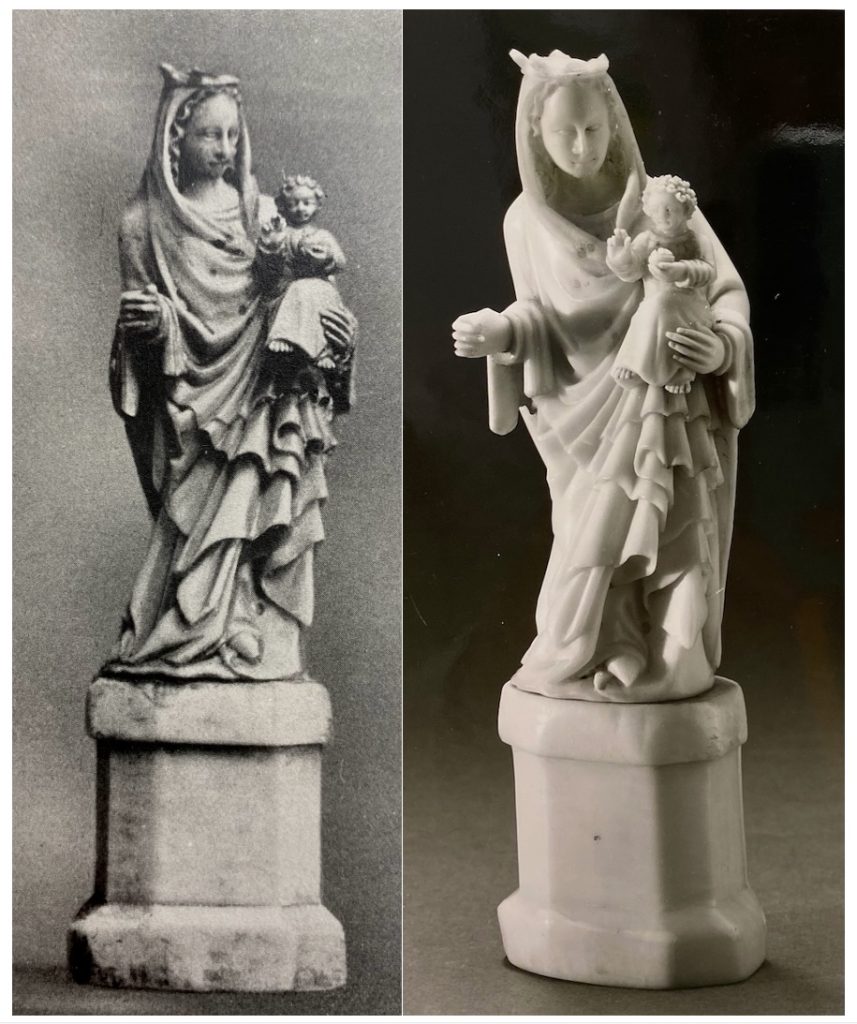

Sometimes we found research clues in unorthodox sources. While researching an early fourteenth-century statue of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna del Fiore, Art History Specialist Jessica Savage found images shared by the Associazione di Festeggiamenti di Lugnano, Rieti on Facebook. According to the association’s website, the statue is mounted on a gilded decorative support and processed through the streets of Lugnano during the “Festa della Madonna del Fiore” every first Sunday of September.4 It was fascinating to see the medieval relic in celebratory use to this day, and it is just as easy to imagine the lives of these various objects as they were gifted, traded, used, venerated, and now discoverable online with the Index database–many digitized for the first time.

Many of the objects and fragments on which we worked had been dispersed either before or after their records were created, and some items or even whole collections had changed hands. Sometimes this provoked unexpected collaborations: in one case, Art History Specialist Maria Alessia Rossi cataloged the right wing of a diptych in the Musée de Cluny depicting the Coronation and Dormition of the Virgin, and then, about a year later, Savage found the other wing, with the adjoining scenes of the Last Judgment and Adoration of the Magi, separately cataloged in the file of the Paris Cabinet des Médailles. The diptych wings are now digitally reunited as Index System number mar20230306003.

Reflecting on the ivories project, Index Director Pamela Patton said, “One of the most exciting things about cataloging the ivory backfiles was the chance to bring elements of a single object that had been dispersed over time into a single work of art record, as for the Casket of Saint Emilianus (San Millán), a reliquary made in the eleventh century but damaged when the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla was sacked in 1089.” Some of the ivory plaques remain in the monastery, but others were dispersed to at least seven different museums in Europe and the United States. Patton recalled, “Bringing together images and metadata for all these works, including one plaque that was lost in World War II but preserved in a German photograph, was a very satisfying endeavor.”

Byzantine rosette caskets were another category that some researchers may find intriguing. Art History Specialist Henry D. Schilb created a record for the Hermitage Museum’s inv. no. Ѡ17, now Index System number hds20250128001, one of a group of similar caskets cataloged by the Index over the years, with examples in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (inventory number Kg 54:219, Index System number 77286) and the Cleveland Museum of Art (inventory number 1924.747, Index System number 77285). Known for the prominent use of rosette ornament, this group of caskets has also attracted the attention of no less eminent a scholar than Princeton alumnus Justin Willson, whose recent article discusses why we find among scenes of Adam and Eve the figure of Plutus holding a moneybag.5

New iconographic subjects encountered during our work on ivories were sometimes added to the Index database during cataloging. For example, the bust portrait of “Ulpia Sirica,” a second or fourth century woman from Rome, was discovered by Rossi in the ivory files. The only known depiction of Ulpia on this opus sectile-style plaque, made of marble, blue and green enamels, glass paste, and painted bone and ivory listels, was buried by a landslide in the late 1900s. Her portrait is last known to have been embedded in a Latin epitaph in the Catacombs of Saint Agnes in Rome; it is preserved in a late nineteenth-century watercolor by Salvatore Merola, kept in the diary of Ubaldo Giordani.6

Additionally, the little-known female saints “Oderade of Quedlinburg,” “Agnes II of Quedlinburg,” and “Pusinna, Saint” inspired new iconographic research by Art History Specialist Catherine Fernandez during her work on the Reliquary of St. Servatius now housed in the Stift Quedlinburg, Domschatz. The rarely depicted religious women, a prioress, abbess, and hermit, respectively, appear in an iconographic grouping, or relic list, with other saints on the bottom enamel panel of the Reliquary of St. Servatius. The ivory reliquary was made in Fulda or Metz around 870 with gem and metalwork additions ca. 1300.

The ivory cataloging project produced a new authority in the Style/Culture category. We added the heading “Forgery” to describe objects that, although executed in a “medieval” style, were actually—and often with deceptive intent—produced by more modern artists.7 The project also required the verification of a great many locations, part of Schilb’s ongoing project to make the location data used by the Index as accurate and precise as possible.

Indexers celebrated the completion of the ivories project with all staff at an in-house celebration that featured appropriately pale but delectable treats (popcorn, burrata, white chocolate-covered almonds, vanilla meringues!) and offered a chance to reminisce about highlights from the project.8 Many more ivory objects remain to be cataloged by the Index in years to come, but for now we are thrilled to make available online all the objects that have been cataloged by the Index to date. We acknowledge there might still be missing or outdated information on some of these records. Sometimes images could not be tracked down, current locations could not be verified, or works were presumed lost or destroyed. Our cataloging efforts will always be a work in progress, and we remain open to your corrections, suggestions, and questions.

Please reach out to us via email, and be sure to follow us here for all our latest updates. You can also find us on Facebook and Bluesky.

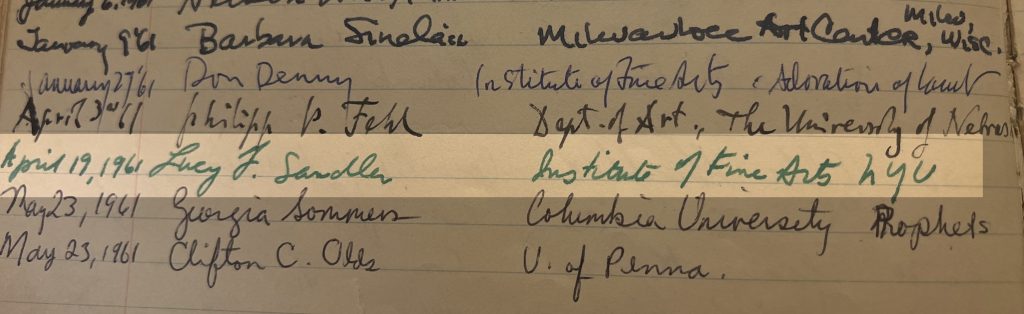

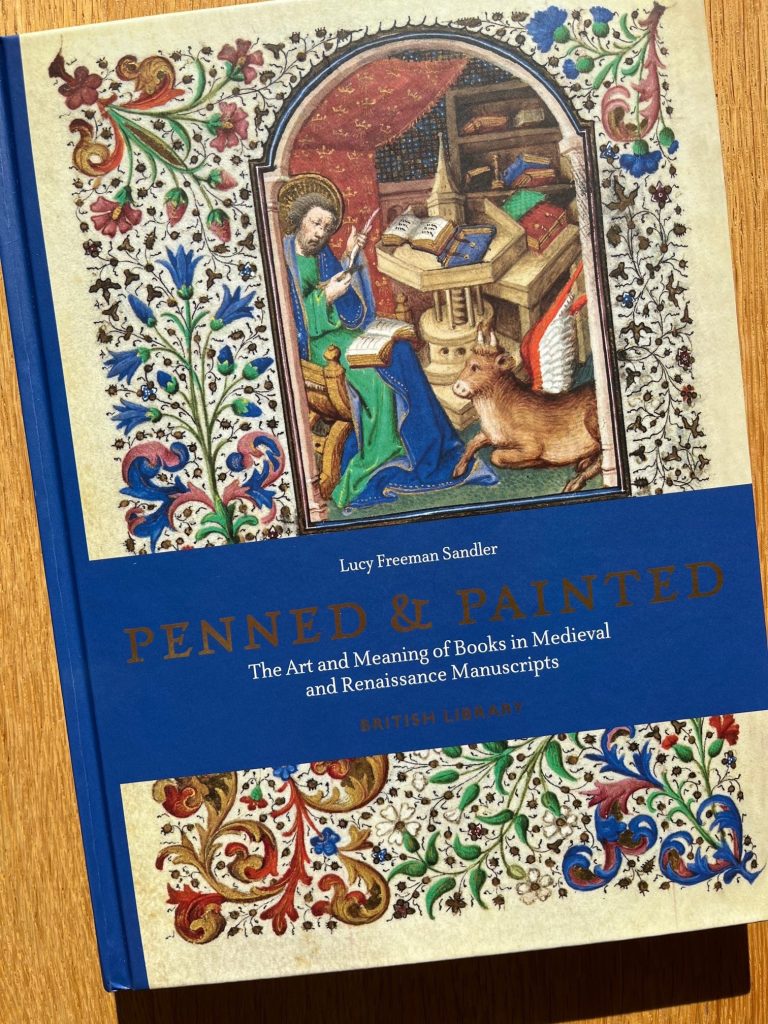

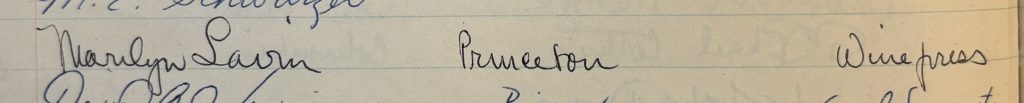

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections and warmly thank Lucy Freeman Sandler, Professor Emerita, Institute of Fine Arts of New York University, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I began to study painting at Queens College but my first undergraduate art history course focused my interest in a new direction, and, inspired by a charismatic medievalist, Frances Godwin, I decided to study the art of the Middle Ages on the graduate level. On Prof. Godwin’s advice I applied to and was accepted at Columbia University and took courses with Meyer Schapiro, a formative intellectual experience, and then with John Plummer, who was then himself completing a Ph.D. with Schapiro. It was Plummer’s course, called “Gothic Painting,” which was primarily about illuminated manuscripts, in which I “discovered” marginal illustrations, a topic that became the subject of my master’s thesis. For my own Ph.D. I transferred to the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University (they generously awarded me a scholarship), eventually completing a dissertation on the Psalter of Robert de Lisle (London, British Library, Arundel MS 83).

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

I cannot remember the date of my first visit to the Index, which Index records indicate was 1961, during the time I was working on my dissertation. I have certainly used the Index many times since, and have known all its directors since Rosalie Green, although, to my regret, I did not meet her.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

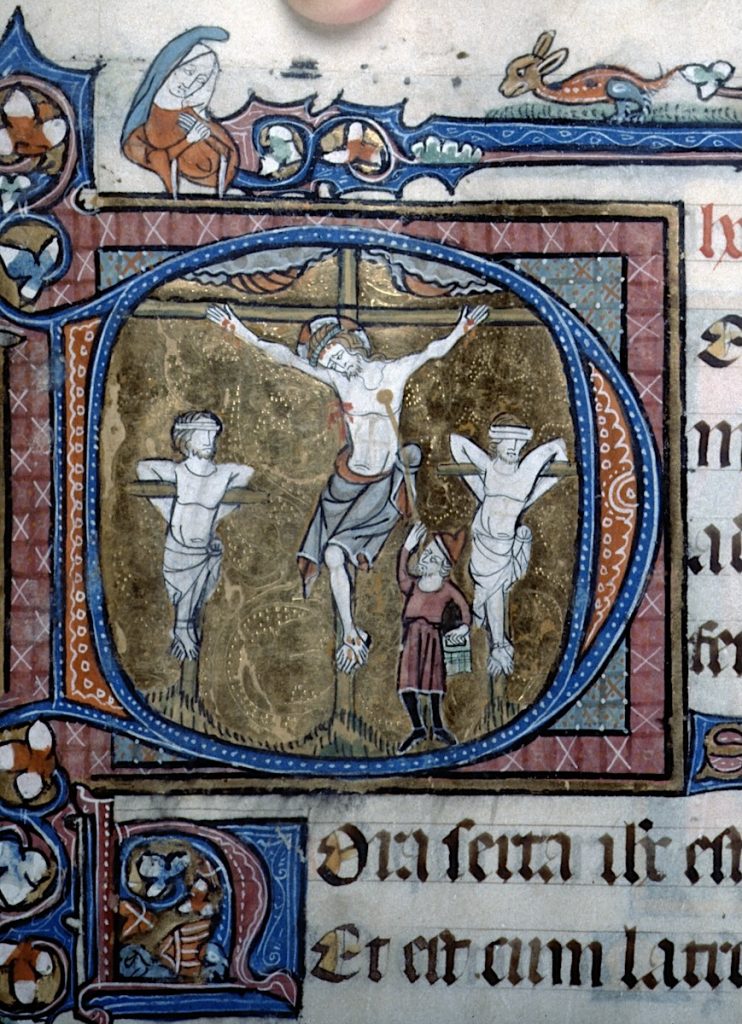

I remember at least one visit, probably sometime between 1961 and 1964, when I was trying to determine the date during the Gothic period at which the crossed feet of the Crucified Christ changed position. I must have looked at hundreds of photos of every late thirteenth and fourteenth century Crucifixion at the Index. I can’t say that I came to any definitive conclusion but I certainly learned a lot about Crucifixion representations. I have found the online version of the Index invaluable, especially in connection with my latest book, Penned & Painted: The Art and Meaning of Books in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts (London: British Library, 2022), for which I did much of the research during Covid.

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I have attended quite a few Index conferences and have spoken at several, including “The Weingarten Office Lectionary and Passionale in New York and St. Petersburg,” in Romanesque Art and Thought in the Twelfth Century in Honor of Walter Cahn (October 2006); “One Hundred and Fifty Years of Study of the Illuminated Book in England: The Bohun Manuscripts from the Nineteenth Century to the Present,” in Gothic Art & Thought in the Middle Ages: A Conference in Honor of Willibald Sauerländer (March 2009); “The Bohun Women and Manuscript Patronage in Fourteenth Century England,” in Medieval Patronage: Patronage, Power and Agency in Medieval Art (October 2012); and “Princeton Garrett MS 35 and Homeless English Gothic Manuscripts,” in Manuscripta Illuminata: Approaches to Understanding Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts (October 2013). All these were subsequently published under the editorship of Colum Hourihane. I also contributed a tribute to John Plummer: “John Plummer: A Reminiscence,” in Between the Picture and the Word: Manuscript Studies from the Index of Christian Art, ed. C. Hourihane (University Park, PA, 2005), 9–11.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As co-editor of the Index-based Studies in Iconography, from 2009–2015, I hoped to serve the mission of the journal, as it has continued to the present, to publish “innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed.”

Thank you, Lucy! As the home for Studies in Iconography we’re committed to publishing innovative work in iconographic studies, and we’re grateful for your invaluable contributions to the Index over so many years.

The Index is pleased to announce the launch of a new digital resource for the study of Byzantine iconography, the Lois Drewer Calendar of Saints in Byzantine Manuscripts and Frescoes. Compiled by the late Lois Drewer, PhD, longtime specialist in Byzantine art at the Index, this calendar identifies saints, cites standard and hagiographic references (with a guide to their abbreviations), and concisely describes manuscript illuminations and frescoes. The calendar is organized by feast days in the Constantinopolitan calendar.

There are four main ways to browse the resource. The first is by selecting a month and day under the tab for calendar. This entry point leads to the core of the data, and we recommend this as a good place to start. For example, searching today’s date of the fifth of March reveals three entries for saints: 1. Mark of Egypt; 2. Conon the Gardner; and 3. Hypatius of Gangra. The list you will find there offers identifications, references, and examples.

Many of the saints and holy martyrs included in Dr. Drewer’s calendar are obscure or infrequently represented in medieval art, such as Conon the Gardener (also known as Conon of Perga), a gardener from Nazareth martyred under the Roman emperor Decius (r. 249–251 CE).[1] In some cases, the iconography has not yet been cataloged by the Index, making this an especially useful additional resource.

There are also two lists for iconographic motifs and iconographic scenes with feast days linked on the right, and a list of feasts days organized A to Z. The iconographic motifs and scenes are grouped alphabetically beneath bold headings.

A majority of the headings in this resource cover martyrdom and torture scenes for Byzantine saints–among them holy martyrs, hermits, prophets, and women, but Drewer also included groups for various vestments and clothing, human gestures, attributes, and objects. For example, it is possible to see that an axe is associated with John the Baptist.

In some examples of medieval iconography, the preaching John the Baptist is depicted pointing to an axe at the base of a tree, a reference to Matthew 3:10. Or you can discover that the representation of grief is linked to Sophia of Rome, who is portrayed in various scenes as mournfully throwing out her arms in response to the beheadings of her daughters Pistis, Elpis, and Agape.

There is much to discover by browsing these lists, and we expect that this resource may usefully supplement your searches within the wider Index of Medieval Art Database. You may also try browsing the Svetlana Tomeković Database of Byzantine Art for similar themes represented in Byzantine art. We welcome your feedback, and we look forward to receiving questions through our research inquiries form.

We warmly thank the Index’s Technology Manager Jon Niola for bringing this project to fruition. Lois Drewer dedicated much of her life to iconographic research, and we feel certain that she would have approved of this posthumous tribute. We are proud to offer this additional resource so that all may benefit from Dr. Drewer’s calendar of saints.

[1] Drewer’s database notes three instances of the iconography of the holy martyr Conon the Gardener: a small illustrated Menologion, 1322-1340 (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. f. 1, fol. 30v), and two frescoes in the south aisle of the narthex in Dečani and in the dome of the south tower narthex in Treskavec, all of which have yet to be added to the Index database.

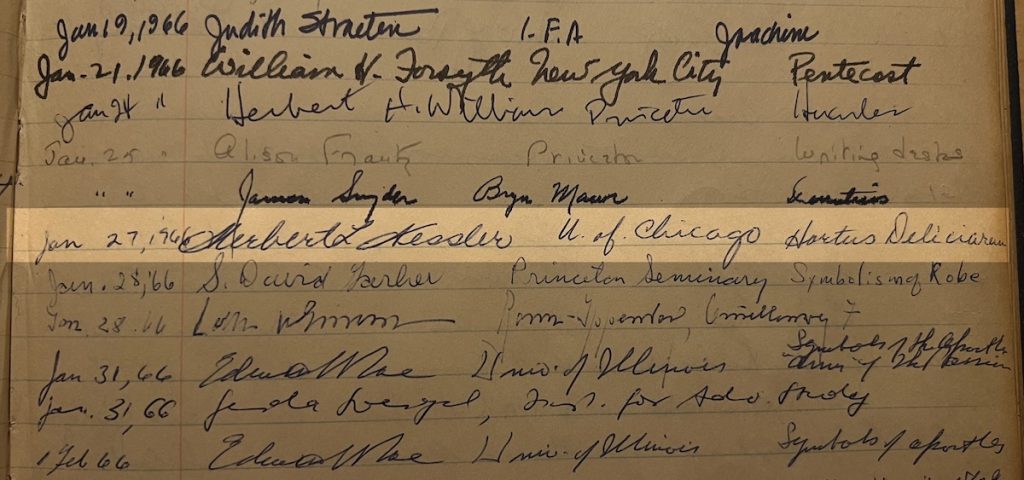

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and we warmly thank Herbert Kessler, Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins University and Index friend, for his time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

After studying medieval art as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, I completed the MFA and Ph.D. at Princeton. At UC, Margaret Rickert had inspired me to become a medievalist; she was also Rosalie B. Green’s Doktormutter, so Rosalie and I had a special bond from the start. I continued to use the Index at Dumbarton Oaks when I was a Fellow there in 1965–66 and then, again, when I returned to Princeton as a Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in 1969–70.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

RBG1 oriented all new graduate students, so 1961. The Index was then in the Neo-Gothic Cram wing of the original McCormick Hall. Graduate students had keys and used it steadily, especially as a picture resource. The Index staff felt under-appreciated and with good cause: though RBG and Isa Ragusa were distinguished and consistently professional and helpful they knew that the faculty did not respect them as scholars. When I was being recruited to the University of Chicago faculty in 1965, the Dean offered to acquire a copy of the Index for me (because William Heckscher, who had been offered the position earlier, had asked for one), but nothing came of that. As computers were evolving in the 1980s, the Getty Center hired two young persons to recommend ways in which the Index might be digitized. Things did not go well, and I was sent (from Johns Hopkins) to reconcile the Index staff with the Getty interlopers. During the discussions, we all realized how the new technology might allow the Index to be modified in ways better to serve other disciplines, especially e.g. by refining types of musical instruments, botanical and zoological species, or agricultural implements.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I have never used the Index for teaching and, frankly, cannot remember a single eureka moment while using it (except, of course, finding a picture I did not know).

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I gave papers at Iconography at the Crossroads2 and Romanesque Art.3 Both were very important gatherings and publications.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As recently as twenty years ago, one of my own graduate students brushed away an argument with “That’s only iconography,” “Only” was the operative word there. In the wake of the material turn, decolonial turn, global turn, historiographic turn, experiential turn, the ornamental turn, . . . . , searching for texts that identify medieval subjects is no longer sufficient. And with the Patrologia Latina and other compendia online, it is not even fun. Simply to dismiss iconography, however, is ignorant. As I myself have argued at length in a recent essay, “the interweaving of text and image and the sensual pleasure of [medieval art’s] color and rich materials” was the essence of medieval art.4 Iconography is therefore destined to remain a fundamental instrument for studying it.

Please join us and register for the next virtual database tutorial with the Index on Tuesday, March 25, 2025 from 12:00 – 1:00 pm EST.

Read more about it at this link: https://ima.princeton.edu/index_training/.

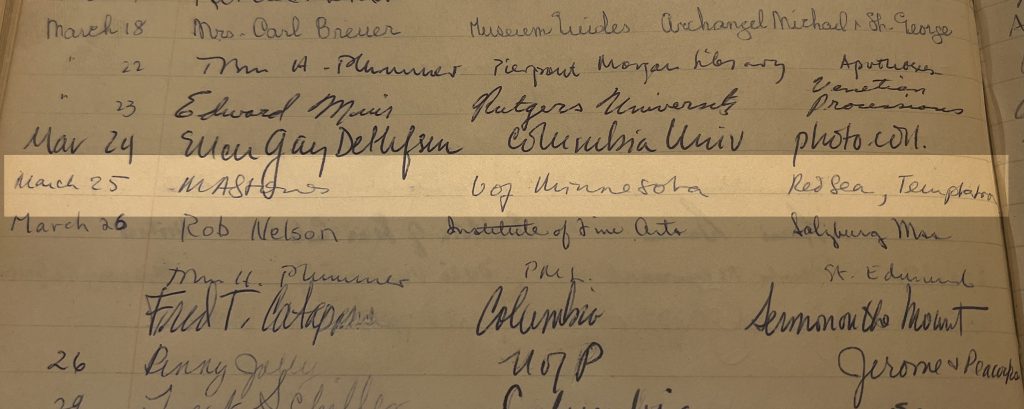

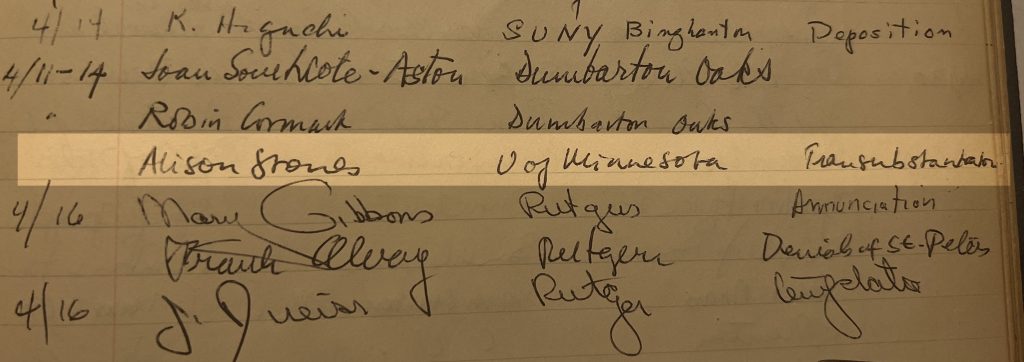

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank Alison Stones, Professor Emerita, University of Pittsburgh, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

In the Fall of 1969, I emerged as a not-quite Ph.D. from the Courtauld Institute (that happened a year later in December 1970/January 1971) to begin what would turn out to be a life-long academic career in the United States. My academic background was in French and German literature, followed by a medieval art and architecture specialty at the Courtauld where I worked with the inimitable Christopher Hohler, and with David Ross at Birkbeck, with musicology from Ian Bent at King’s and Heraldry with Nick Norman at the Wallace Collection.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

By 1969 I already had many friends in the US, notably Adelaide Bennett at the Index, Paula Gerson then at Fordham, James Marrow at Binghamton, and Bob Deshman at Toronto, Canada. All of them had worked alongside me in London, so the transition to the US was easy for me and all of them made me feel welcome there. The Index, under Rosalie Green, was among my first stopping places and continued over the years to be a haven for my research on French illuminated manuscripts, from the days of the invaluable old card system up to the new innovations of the 21st century. Adelaide and I would argue back and forth over the limitations and benefits of “Index-Speak” which invited us to hone our descriptive (and analytical) skills, and more recently it was a pleasure to encounter my former student Judith Golden among the ranks of the Index staff. One simply learned so much there!

Under Colum Hourihane came the era of the Index conferences, not-to-be missed sessions of innovative research, captured with regularity in the impressive series of publications produced under his editorship. I was privileged to attend many of these conferences and to participate in Iconography at the Index: Celebrating Eighty Years of the Index of Christian Art (1997),[1] Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus (2004),[2] as well as the festschrift volume Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer (2017).[3] Naturally, these essays all depended heavily on research conducted at the Index, where I must admit that my preference was still the old card system rather than the new, online version. Thankfully, the Index conferences are ongoing, and now available online with a livestream link. From the presentations to the interaction that follows, one learns so much!

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database over the last three decades? Where do you think Index work should go next?

As to future directions for the Index, I wish it could become a repository for the many online medieval databases (my own included) that risk becoming defunct once their creator retires. I appreciate the logistical issues and the problems of different software, but so much creative work is out there, and risks being lost. This in addition to the very valuable repository of information and images that make the Index such an indispensable tool for all medievalists. Long may it continue to flourish and many thanks for all I have learned there!

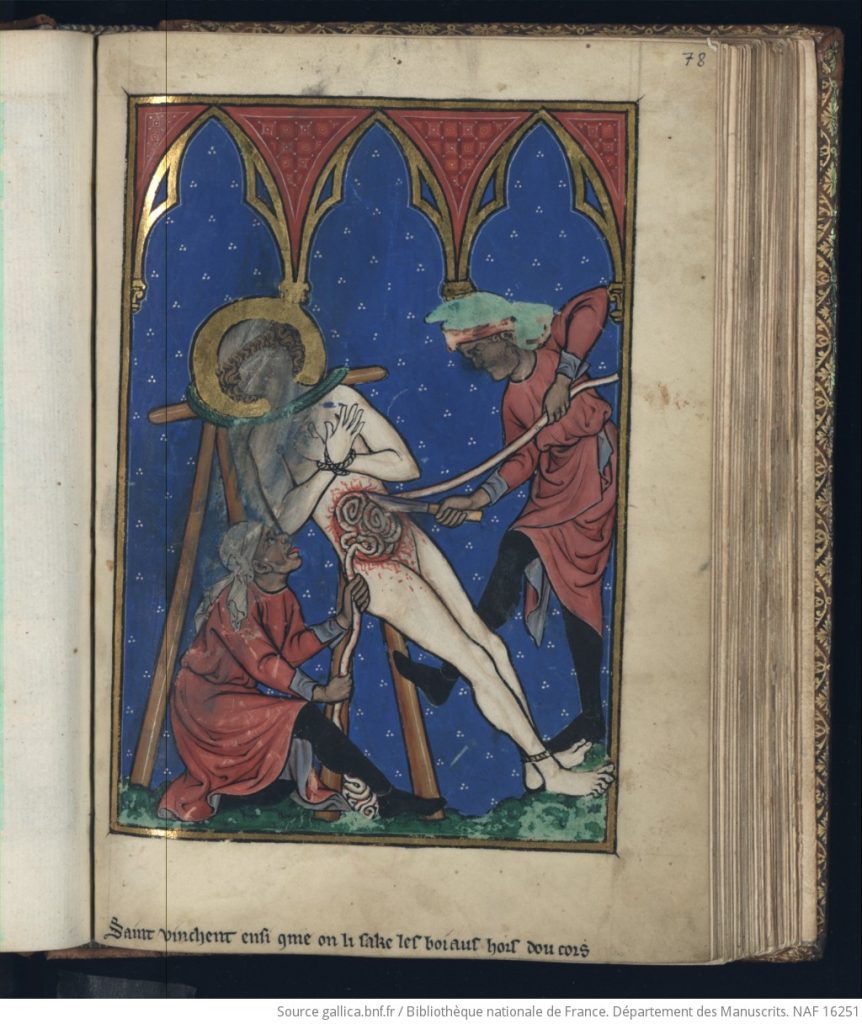

[1] Alison Stones, “Nipples, Entrails, Severed Heads and Skin; Devotional Images for Madame Marie,” in Image and Belief: Studies in Celebration of the Eightieth Anniversary of the Index of Christian Art, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 1999), 48–64.

[2] Alison Stones, “Questions of Style and Provenance in the Morgan Picture Bible,” in Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus: A Colloquium in Honor of John Plummer, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 2004), 112–121.

[3] Alison Stones, “Tobit: A Recently Rediscovered Cutting from the Brussels-Rylands Bible,” in Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer, eds. Pamela A. Patton and Judith K. Golden (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2017), 335–353.

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to launch a new series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank our interviewees for their time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I’m not a medievalist but my work in Renaissance iconography has always depended on research material from earlier times. I had my first course in art history as a senior in high school, Mary Institute, St. Louis, 1942–1943. I majored art history at Washington University, St. Louis, receiving my M.A. (1949) under H.W. Janson, and did graduate work at the Institute of Fine Art, NYU, with Erwin Panofsky and others. I received my PhD on the basis of three related published articles in 1973.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located then? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

My first visit to the Index was in 1950. For a seminar with Panofsky, I was investigating the sudden appearance of the Infant St. John the Baptist in the Florentine early fifteenth century. The Index was in McCormick Hall. I met Rosalie B. Green and worked with her and Isa Ragusa. I also, by chance, met Professor Morey on that visit. I quickly found that the arrangement of the Index card catalog did not offer simple searching under the Baptist’s name. Learning the biblical structure of the index then helped me broaden the conceptual basis of my project and enriched my results.

In my years of working in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, it was always reassuring to know that the copy of the Index was there for consultation. In the 1980s, when I was a member of the Getty AHIP team, the precedence of the Index was a motivating factor in creating new computer tools for art historical research.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I am told that my article on the iconography of the Infant St. John, published in 1955 in The Art Bulletin remains useful up to the present day.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database? Where do you think Index work should go next?

With the appointment of Pamela Patton, the Index has finally hit its stride. Along with its change of name, broadened constituency, and superb technical improvements, the Index is fast becoming a major research center. It seems to me obvious that these advances indicate that the direction The Index of Medieval Art is going is the right one.

This blog post is the ninth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce our student worker Brooke Jurgenson.

What year are you in your Princeton education? What are some of your favorite courses or subjects?

I am a second-year student in the Class of 2026. I intend to declare psychology as my major, but I also love philosophy, literature, and art history. My first year, I really enjoyed the Western Humanities Sequence, which traced the development of the Western intellectual tradition through such foundational works as Augustine’s Confessions and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This semester, I am bridging my interests in psychology and philosophy with the course “The Psychological Foundations of the Mind” and branching out into linguistics by taking “On the Origins and Nature of the English Language.”

What do you do at the Index?

At the Index, I go through different iconographic categories, such as Virgin Mary, Dormition and Christ, Presentation, and add subjects to make the categories more comprehensive and accessible for researchers. For instance, I might add the subject tags “Joseph the Carpenter,” “Anna the Prophetess,” and “Dove” to all the records containing this imagery in scenes of the Presentation of Christ. I also collaborate with the Index research staff on refining the subject taxonomy and applying it more widely to records.

Aside from your experience at the Index, what was the most interesting job or internship you had?

In addition to fostering a love of medieval art at the Index, I have learned much about Princeton’s modern sculpture collection by serving as a Student Art Tour Guide with the Princeton University Art Museum. I lead small group tours around Princeton’s campus, highlighting the subtleties of Henry Moore’s bronze craftsmanship and Jacques Lipchitz’s mysterious abstractions.

What have you learned about medieval art since working for the Index? Has anything surprised you, or does anything stand out as extraordinary or curious about medieval art?

I absolutely love medieval art! Beautiful florals, ornate Latin scripts, gold pigments, and captivating renditions of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child regularly grace my screen. My appreciation for medieval art has grown immensely, and I have come to recognize just how rich and varied the subject area is.

I also never fail to come across the most mysterious and fun “hybrid creatures.” It is only here that I stumble across cats playing hurdy-gurdies and half-dragons slaying monsters. Medieval art truly expands your imagination.

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

This past summer, I took a somewhat impromptu trip to Berlin and visited the Bode Museum. I reveled in the amazing Byzantine collection there. Aside from medieval art, I enjoy Impressionism because of how it captures the ephemeral. My favorite work (as of right now) is Claude Monet’s “View of Vétheuil” painted in 1880, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Accession number 56.135.1).

What’s your favorite building or spot to sit on campus?

When it is warm outside, I love sitting on a bench in the garden behind Maclean House while reading. It is the perfect place to listen to the birds sing and feel the serenity of nature. I also love gazing at the stained glass windows of the Princeton University Chapel, watching the colorful dances of light play out in the sacred space.

Coffee or tea?

I avidly drink both coffee and tea, but I am a tea lover by heart. A steaming cup of freshly brewed green tea is all I need to be content.

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2024.

Although some scholars have claimed to see something like pizza in a wall painting at Pompeii, most historians trace the origins of modern pizza to sixteenth-century Naples. However, researchers at the Index of Medieval Art have discovered previously unrecognized medieval evidence of pizzerias in manuscripts dating at least two centuries earlier.

These early pizza-making scenes depict workers baking crusts, as in the miniature of a fifteenth century Book of Hours (Princeton University Library, MS Garrett 54). Notice how the pizza chef thrusts a long-handled peel with a round crust into a roofed pizza oven. Other steps in the preparation of crust have been identified in the iconography of pizzerias, including a hybrid figure tossing a circle of dough into the air to give the pizza its custom shape. Tossing dough in the air has long been the preferred method in pizza preparation to thin out the crust and give it its signature stretchy, glutinous finish.

Our research found that the toppings for pizza throughout the medieval period would have run the gamut. The typical meats and vegetables that popularly eaten today would have featured on pizza in the Middle Ages, too…with one major exception: the edible berry of the plant Solanum lycopersicum, more correctly identified as the Amoris pomum and commonly called the “the tomato.” Tomato sauce on pizza was strictly prohibited due to the prevalence of the belief that the love apple is the devil’s fruit. But pizza was always a highly customizable dish, and pizza mongers were apt to use any combination of sauces with any number of toppings to suit their palates. Pineapple and anchovies on pesto with casu martzu was a particular favorite among both penitents and unrepentant heretics alike.

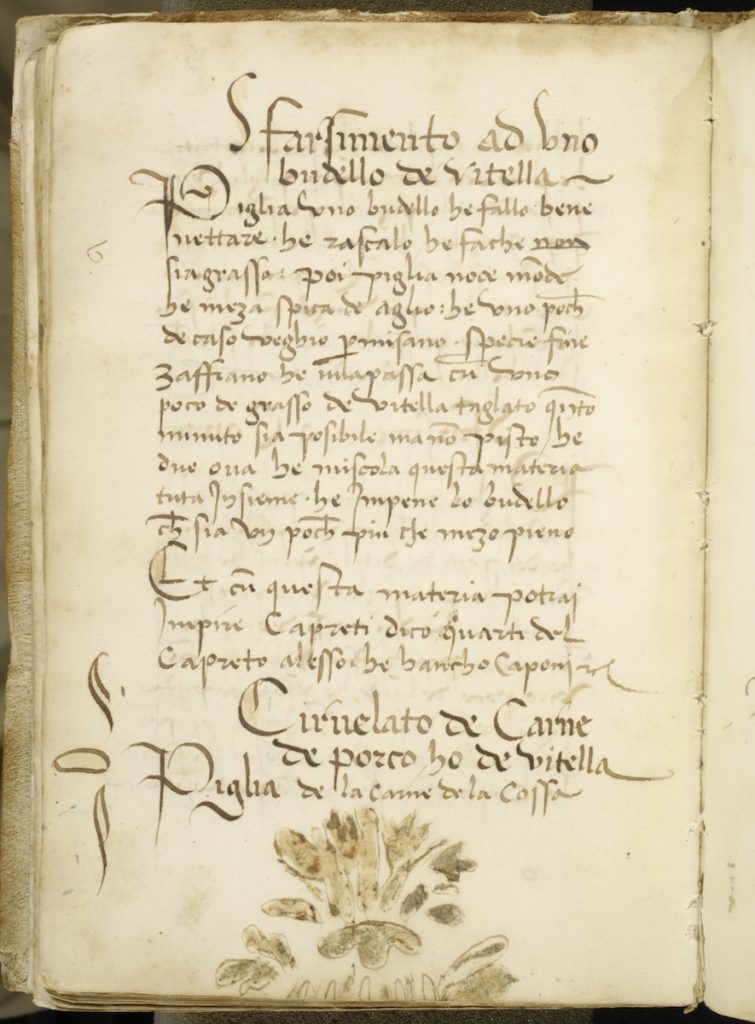

You can imagine our surprise at finding in one late fifteenth-century Neapolitan cookbook, known as the “Cuoco Napoletano,” a recipe for a type of blood sausage known as cervellato (manuscript inscribed “Cirvelato de carne de porco ho di vitelli”) with a mention of its use in pizza preparation. Legendarily, and much like today, sausage was a favorite topping among medieval consumers of pizza, and the following leaf in the cookbook describes such usage in great detail. Or are you a fan of fungi on your pies? Mushrooms too made it onto the menus of pizza chefs, and some illustrations in medieval manuscripts show the fleshy morsels lined up and ready to chop.

Whether deep-dish or thin with extra cheese, pizza was prized in the Middle Ages. Pizza to go wasn’t out of the ordinary, either, but the pie would have to be fiercely guarded by its consumer. Eating a slice, or “wolfing ’za” as the medieval collegiate vernacular would have it, was often a perilous, two-handed operation. In one medieval image, you’ll notice that a large man chowing down on a delicious slice folded in one hand was required to wield a club with his free hand to ward off would-be pizza poachers!

It was also a seasonal favorite. Such early forms of a pizza would have been regarded as the perfect addition to any menu on the first day of April.

(And by the way, April Fool!)

We are very pleased to announce that Kyriaki Giannouli has joined the Index remotely for a three-month, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works on Mount Athos (Greece) into the database!

Kyriaki is a doctoral candidate specializing in Byzantine History at the University of Ioannina and a professional conservator of paintings. Her research focuses on examining the significance of Greek landscapes within the travelogues of Western Holy Land pilgrims from the 12th to the 17th centuries. She is an expert in Byzantine portable icons, frescoes, coins and seals and has hands-on experience in creating specialized conservation reports and working with databases.

At the Index, Kyriaki has started working on enamel and metalwork backfiles and has already made digitally available several objects on Mount Athos, including a fourteenth-century chalice from Vatopedi monastery (Index system number mar20240205001) and an eleventh-century book cover from Lavra monastery (Index system number mar20240212001). Her position requires her to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. This will allow scholars worldwide, who are not able to travel to use the print Index on the Princeton campus, to access these images and their metadata. We are very excited and grateful to have Kyriaki join us in this collaboration!

This position is part of a multi-year project focusing on Mount Athos-related collections at Princeton (https://athoslegacy.project.princeton.edu/) and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.