June, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc du Berry (Chantilly, Musée Condé, 65/1284), fol. 6v © Photo. R.M.N. / R.-G. Ojda

The Index will be closed on June 4 and 5 as Princeton celebrates Class Day and Commencement 2018. We look forward to welcoming visitors during Princeton University weekday summer hours, 8:45-4:30, beginning June 6.

It’s easy to assume that medieval iconography was unchanging: that after a particular way of representing a saint or scene was invented, it became fixed in tradition. Not so! Medieval iconography and the stories that lay behind it moved constantly with the times, adapting over the centuries to the local beliefs and practices of their surrounding communities. Many of these post-medieval adaptations were frankly anachronistic, as is the topic of the present post, which also happens to be of central importance here at the Index: coffee.

Coffee was not a medieval beverage; the earliest evidence of its consumption in this form derives from fifteenth-century Yemen, from where it spread to other parts of the Islamic world, reaching Ottoman-ruled Constantinople in the sixteenth century and western Europe soon after. Where it was traded most actively, it inspired import companies, coffeehouses, and coffee-centered social practices, eventually even percolating (!) into medieval artistic and legendary traditions to which it had no original connections at all.

One example of this trend is Saint George’s “coffee boy,” a name sometimes given to the small figure holding a vessel who rides behind the saint on certain Byzantine and “post-Byzantine” icons (Fig.1). The type for some time puzzled scholars, who now conclude, on the basis of written sources, that such scenes depict Saint George miraculously rescuing a Christian captive.

However, the path to this conclusion was once obscured by alternative local interpretations. One legend that still circulates today in some villages in Cyprus explains that Saint George was drinking coffee when news reached him of the princess he was to rescue from a dragon. With no further ado he mounted his horse, and the coffee boy immediately followed him with his beverage, allowing the saint to finish it on the ride. While the legend seems unlikely (to say the least), our interest lies in how this conflation came into being. Why would the explanation of this image rest on coffee, a beverage unknown either to the third-century saint or to the medieval icon painters who portrayed him?

To answer this, we must return to the two original legends that inspired this iconography. In the former, the young boy was captured by the Bulgarians. He was so handsome that their ruler made him a steward and kept the boy in his residence. On the same evening Saint George rescued him, the ruler had asked him to bring water for hand-washing during the supper in the palace. In the second instance, the boy was taken into captivity by the Saracens and was made the personal cupbearer of the Emir of Crete; he was in the act of offering a glass of wine to the Emir when Saint George appeared and rescued him. The first representations of this iconography, in which the boy holds either a cup or a ewer, appeared in the twelfth century and then spread in the Eastern Mediterranean, where they promoted the role of Saint George as defender of Christians in areas threatened by foreign invasion. Not surprisingly, the type became even more widespread in Orthodox icons after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Ottoman Empire.

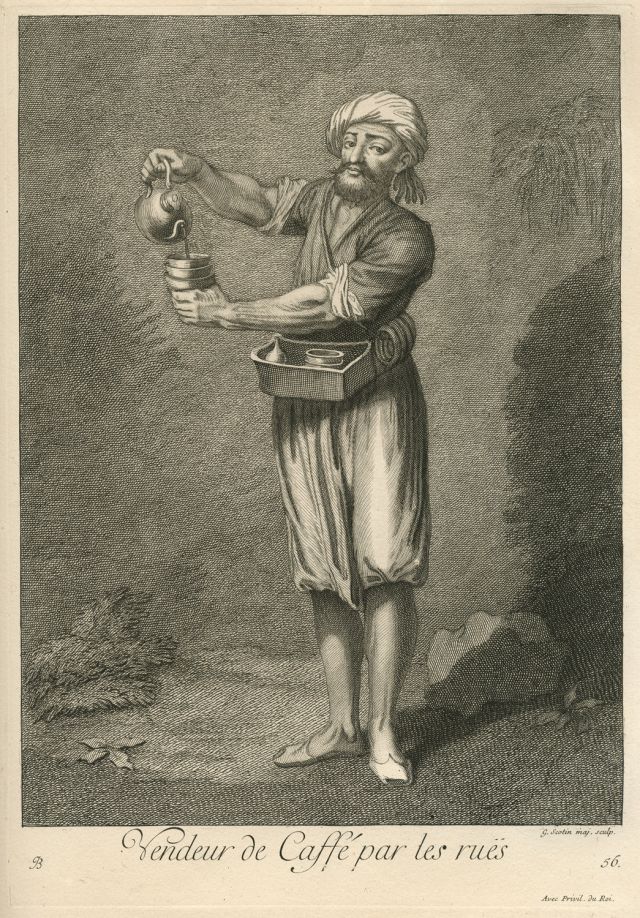

In this later period, the representation of the miracle of the captive boy was often conflated with the more famous episode of Saint George killing the dragon and saving the princess (Fig. 2). This compositional transition combines the two miraculous episodes to reinforce the original connotation of protection from “infidels,” embodied by the young boy, and of the fight against evil, symbolized by the dragon and the unharmed princess. After the sixteenth century, the garments worn by the young boy reflect contemporary fashion under the Ottoman rule: baggy trousers, a yelek (vest), a cebken (jacket) and a distinctive hat. The opacity of the ewer he holds, which resembled a coffee pot, may have led to the boy’s identification as a coffee server, much like the vendors found throughout Ottoman-ruled lands (Fig.3). Like so much medieval iconography, the interpretation of St. George’s “coffee” boy thus tells us much more about the preoccupations of a changing early modern society than it does about George’s own hagiography.

The association of coffee with St. Drogo, a French saint venerated at Sebourg, has even more circuitous history. Since about 1860, Drogo has been credited as the patron saint of coffeehouses, especially in Ghent, but the reasons for this remain obscure. A twelfth-century orphan, he early devoted himself to penance, pilgrimage, and charity, giving away all that he earned as a shepherd beside what he needed to stay alive (Fig. 4). When a painful hernia made work and travel impossible, he settled down as a hermit in Sebourg, living on a bare ration of brown bread and warm water until his death in 1186.

Drogo’s hagiography offers nothing that might link the saint to coffee besides his penchant for drinking warm water, and this might have encouraged his association with the beverage. However, it may be worth considering that in the mid-nineteenth century, when the saint’s link to coffeehouses is first recorded, his cult center of Sebourg was also renowned for the production of chicory, a plant used in combination with coffee and as a coffee substitute in both France and the Low Countries from the late eighteenth century onward. Could the local chicory trade have encouraged St. Drogo’s association with coffee drinking? We would love to hear from historians who may have an answer to this mystery.

Anachronisms aside, what St. Drogo and the “coffee boy” tell us quite clearly is how flexibly saints’ lives and iconography responded to the changing priorities of the communities around them. The same flexibility more recently has given us Saint Claire as the patron saint of television and Saint Isidore of Seville as patron of the internet. What new saintly protectors will the 21st century bring? There’s a question to ponder over your next cup of joe.

Contributed by Pamela Patton and M. Alessia Rossi.

Isidore of Seville (?) at his desk, from the Stuttgart Psalter (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, MS 23), fol. 1v

As our subscribers will have heard, refinements of the new Index database application are proceeding on schedule, and on March 30 it will become the primary and only route to online search of Index records. We think you’ll find the new platform much more user friendly and appreciate features such as filtered searching, a date slider, and (mirabile dictu) immediately visible thumbnail images.

Subscribing institutions should be switching the URL to https://theindex.princeton.edu, and some may have done so already. You should also be able to access the database by navigating to this URL if you are on site and using the IP range of a subscribing institution.

If you’d like a jump start in using the new system, please check out the tips below. Your feedback is welcome at theindex@princeton.edu.

Follow this link to reach the landing page:

https://theindex.princeton.edu/

Once there, click on the “Search” dropdown and choose “Advanced Search.” Type one or more keywords into the “Search Expression” line for a Boolean search, which can be filtered by Work of Art Type, Creator, Location, etc. in the fields below; dates can be refined using the slider. Exact-phrase searching iis coming in the next few weeks, so if it isn’t active when you visit, please check back.

Clicking the search button calls up a results list that appears below the search filters; click thumbnails to see the full records. Works can also be searched for by browsing the Index authorities for Subject, Creator, Patron, among others; each authority includes an expandable bar containing to the records in which the term appears.

As you try out the site, please remember that some design elements and search tools are still actively in development: layout, terminology, and search dynamics still may change. This makes your feedback all the more useful, as it helps us to evaluate future refinements. We look forward to hearing from you!

The medieval New Year was not always celebrated on January 1. Although this was the first day of the Roman civil calendar, which eventually was adopted in much of the medieval world, people of the Middle Ages often marked the start of the year with celebrations on March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation; on the near-springtime date of March 1; or even on Christmas or Easter. Nonetheless, in medieval iconography, January continued to be associated with images of the ancient Roman deity Janus, who personified both the month and the transition and reflection that accompanied the change of the year.

Fig. 1. Coin with laureate head of bearded Janus, 209–208 BCE (or later). Crawford 100/1a (citing 6 specimens of all varieties in Paris); Sydenham 309a.

Janus was among the oldest gods venerated in ancient Rome, where he was associated with doorways, gates, and arches (one word for which was the Latin ianus) as well as temporal transitions. Ovid’s Fasti, an unfinished Latin poem on the Roman year, opens the kalends (first day) of January with an appeal to “Two-headed Janus, source of the silently gliding year, /The only god who is able to see behind him,” asking him to bring a favorable year. As early as the third century BCE, Janus was commemorated on coins as a bust with two bearded faces looking in opposite directions from a single neck, illustrating his ability to see both past and future (Fig. 1).

Janus’s status as overseer of temporal change persisted into the Middle Ages. In City of God (Book 7, ch. IX), Augustine wrote that “ad Ianum pertinent initia factorum” (the beginnings of accomplishments belong to Janus), while in his own Etymologies, Isidore of Seville associates the figure with the month of January and describes his double face as representing the beginning and the end of the year. Although Janus was occasionally represented in other visual contexts, the vast majority of medieval imagery relates to this timekeeping role.

Fig. 2. Calendar from a sacramentary made in Fulda (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, MS theol. Lat. fol. 192, fragm.), ca. 975.

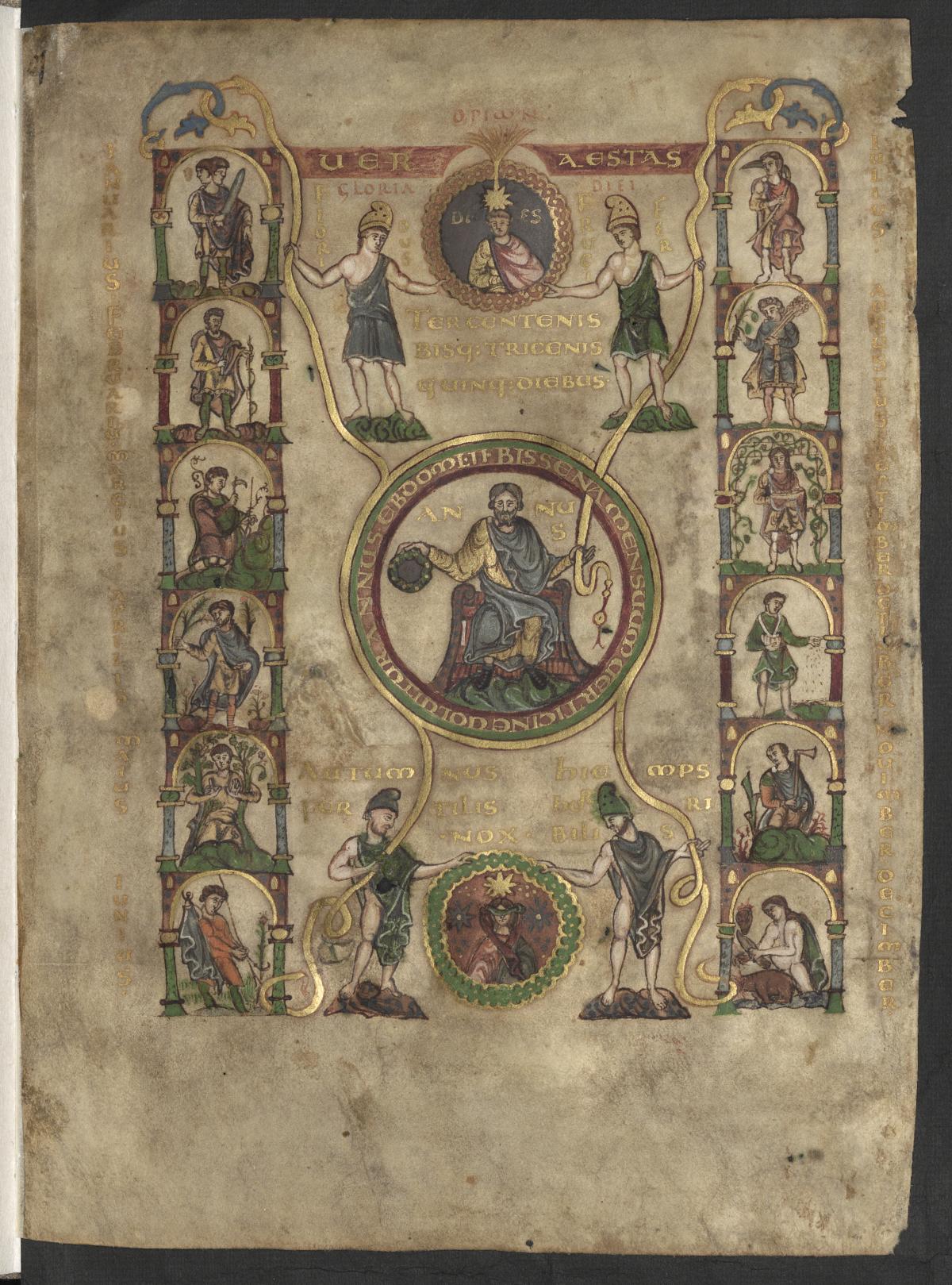

In the Middle Ages, Janus most often appeared as the sign for January in calendrical cycles such as zodiacs and occupations of the months. An early example appears in a calendar page from a fragmentary late tenth-century sacramentary produced in Fulda (Fig. 2). Here, Janus appears at the upper left as a youthful foot soldier with sword drawn, his two faces turned vigilantly over each shoulder.

Fig. 3. Painted roundel depicting Janus, inscribed “Genuarius” (January), Panteón de los Reyes, San Isidoro, León, after 1109.

In the early twelfth-century calendrical cycle painted in the Panteón de los Reyes in San Isidoro of León, a roundel labeled “Genuarius” (January) contains a representation of Janus standing between two portals, the left shut and the right open to suggest the closing of the past year and the opening of the coming one (Fig. 3).

Yet another variant is found on an archivolt of the Ascension portal of the west facade of Chartres Cathedral, which combines depictions of the zodiac with the labors of the months (Fig. 4). Here, Janus displays faces of different ages, one youthful and beardless and the other with a mature beard, emphasizing the passage of time from the old year to the new.

Fig. 5. Janus feasting, Fécamp Psalter (The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, MS 76F 13, fol. 1v), late twelfth century.

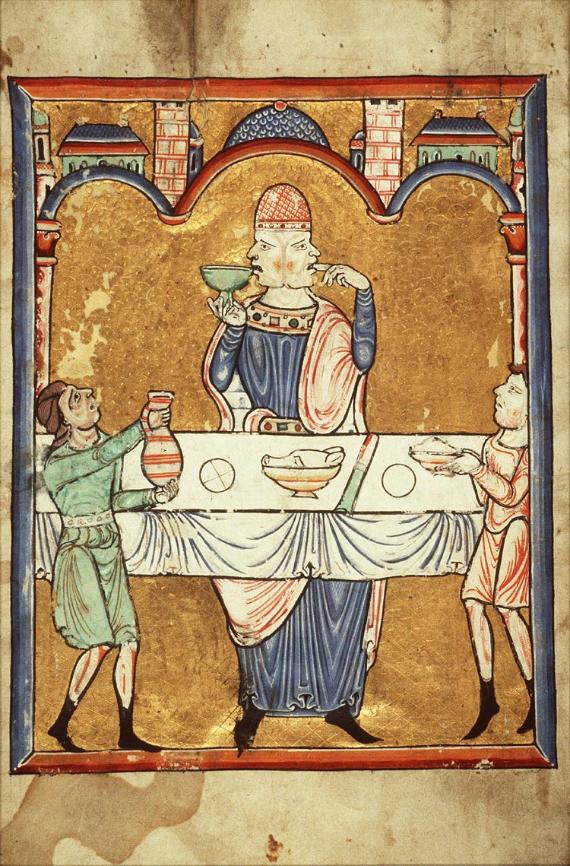

The medieval calendar traditionally associated January with feasting, so it is not surprising that Janus often appears at a laden table, both his faces engaged in eating and drinking. In the late twelfth-century Fécamp Psalter, he sits alone, one face sipping wine from a chalice in his right hand as the other chews a morsel of meat from his left and two servants wait to replenish his meal (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6. Detail of Janus, from January calendar page, Book of Hours (New York, Morgan Library & Museum, MS M. 27, fol. 2v), ca. 1420–1430.

In the medieval west, feasting scenes of this kind became common in the calendars of private prayer books, especially in late medieval Books of Hours. In a lavishly decorated French example produced between 1420 and 1430, possibly in Rouen, Janus sits snugly in a roundel at the bottom of the January page, enjoying double dishes of meat as a servant waits at his elbow (Fig. 6). The connotations of comfort and plenty in such images surely appealed to their wealthy viewers in the dark and cold of winter.

Fig. 7. Triple-faced Janus, detail of stained glass window of the Labors of the Months, Chartres Cathedral, ca. 1220.

The novelty of Janus’s double face sometimes inspired fanciful artistic interpretations. Some artists increased the number of his faces to three or even four, drawing on ancient and medieval traditions that linked the god with past, present, and future or the cardinal directions. A thirteenth-century stained glass window of the Occupations of the Months in the cathedral of Chartres cathedral depicts the figure with three faces; he stands in an open portal beside an image of the Aquarian water-bearer (Fig. 7).

Fig. 8. Janus (?), Luttrell Psalter (London, British Library, MS Add. 42130, fol. 206v), ca. 1325–1335.

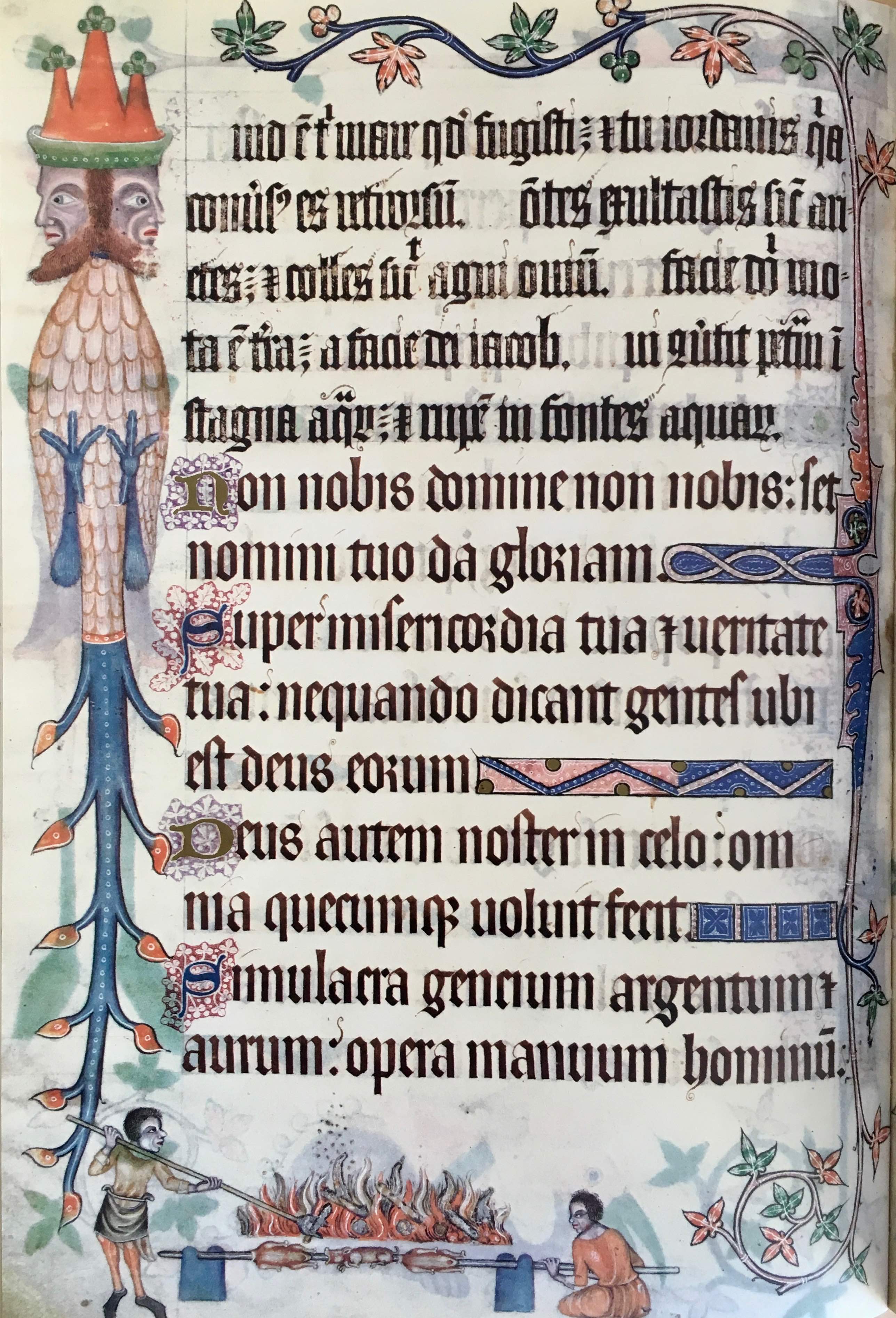

The illuminator of the fourteenth-century Luttrell Psalter, an artist of striking creativity, transformed Janus into a fanciful marginal hybrid, his double face, surmounted by a three-peaked red hat, affixed to a feathered bird’s body with a vinelike foliate tail (Fig. 8). Below, two dark-skinned servants prepare a meal in possible reference to the figure’s traditional feast.

A search for “Pagan Type: Janus” in the beta version of the new Index of Medieval Art database currently brings up 75 results, which can be filtered by date, location, medium, and other delimiters. We encourage you to explore these examples and more at our beta site, available to subscribing institutions at https://theindex.princeton.edu/

Further Reading

Ovid, Fasti, Book I: https://web.archive.org/web/20050419220209/http://www.tkline.freeserve.co.uk/OvidFastiBkOne.htm#_Toc69367257

Kühnel, Bianca. “The Perception of History in Thirteenth-Century Crusader Art,” France and the Holy Land: Frankish Culture at the End of the Crusades. Edited by Daniel H. Weiss and Lisa Mahoney. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004, 161-186, esp. 165-172.

Thraede, Klaus. “Ianus.” Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum. Stuttgart, Hiersemann1994), cols. 1259-1282.

Figure 1. Saint Nicholas of Myra Refusing Milk, ivory crozier, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1150-1185).

December 6 marks the feast day of Saint Nicholas of Myra, the source of our modern-day Santa Claus. We have taken this occasion to showcase the Index of Medieval Art as a tool for learning and researching about the iconography of medieval saints. The Index’s extensive collection of data had already offered users a chance to trace the saint’s history through art, and its archive of medieval images had granted researchers the opportunity to compare iconographies and expand their understanding of saints like Nicholas. Now, the multiple filters in the new database, currently in beta and undergoing daily refinements, allows users to retrieve, browse, and narrow search results in order to highlight the specificities of the saint.

The historical Saint Nicholas of Myra is an obscure figure. We know little more than that he was born in Asia Minor at the end of the third century and later in his life became a bishop of Myra. Nevertheless, he is one of the most popular saints of the Christian church, praised for his victories against demonic infanticide and his capacity of resuscitating dismembered bodies left in barrels to cure (yes, that’s right!). It should really come as no surprise, then, that the Index has 376 records of portraits and more than 600 representations of narratives and single figures of the saint.

But, if Nicholas’s life is virtually unknown, how did his cult and imagery develop to such a degree? The medievalists among our readers will already know that that the answer lies in another Saint Nicholas, that of Sion. The latter lived in the sixth century, and we have somewhat more information about him. Before the 10th century, these two saints, Nicholas of Myra and Nicholas of Sion, were merged by the literary tradition, and the voids left by the life of the former were filled by the latter. The fate of the two saints was sealed, and the archimandrite of Sion fell into darkness while the cult of the bishop of Myra flourished.

The cult of the bishop of Myra spread in both Eastern and Western Christendom. His life is represented in Byzantine monumental painting at least 31 times. The strengthening of his devotion saw a similar trend in the West. By the Renaissance, he had become the most popular saint in Europe. The Index allows for an interesting overview of the different contexts where Saint Nicholas’ cult developed. By browsing the Style/Culture filter, you can find 355 records identified as Gothic, 161 as Byzantine and 89 as Romanesque.

We know very little about Saint Nicholas’ childhood, but the Golden Legend assures us that he was incredibly pious from birth (literally):

While the infant (Saint Nicholas) was being bathed on the first day of his life, he stood straight up in the bath. And from then on, he took the breast only once on Wednesdays and Fridays.

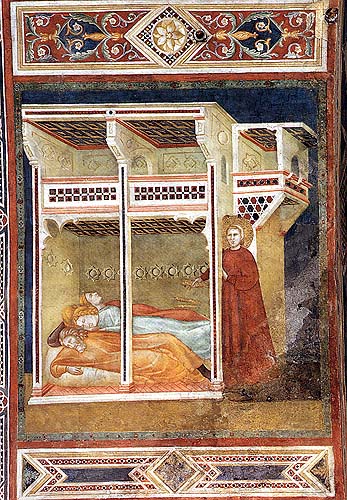

On a Crozier at the V&A, Saint Nicholas is represented sitting on his mother lap (Fig.1). She is offering her breast, but Saint Nicholas refuses, averting his head. With such a start, we should not be surprised that, as a young man, he decided to devote his inheritance to saving three sisters from prostitution (a real-life super hero!). The opportunity arose when a citizen of Myra lost all his money and could not support his three daughters. Nicholas heard of the situation and provided a dowry for each of the sisters. Among the 58 records with this subject identified in the Index database is a fresco in the chapel of Saint Nicholas in the lower church of San Francesco in Assisi (Fig.2). Here, he is represented as throwing three bars of gold through the window of a building where the three sisters and their father are sleeping.

Figure 2. Nicholas of Myra aiding the Dowerless Maidens, detail from the Chapel of Saint Nicholas, San Francesco, Lower Church, Assisi (1300-1349).

The nature of the dowry in this tale ranges from bags to balls to bars to coins of gold. In western iconography, the three balls become an attribute of the saint, and scholars have suggested a link between this and the pawnbroker’s symbol of three golden spheres suspended from a bar.

Besides helping maidens, Saint Nicholas is also known as the guardian of sailors, an exorcist and healer. By using the Creator filter in the Index, it is possible to examine this dimension of Saint Nicholas’s through the eyes of many artists. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, for instance, painted on panel several scenes from the life of the Saint, including that of the Resurrection of the Strangled Boy (Fig.3). The scene takes place in a two-story house, with the narrative beginning on the upper floor with the banquet scene. During the feast, the devil came to the door, dressed as a pilgrim and asking for alms. The boy is represented first at the top of the stairs, answering the door, and later at the bottom while being strangled by the devil. The story continues to unfold in the foreground where the boy is resurrected by the rays descending from Saint Nicholas.

Figure 3. Saint Nicholas of Myra Resurrecting a Strangled Boy by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Panel painting in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence (1300-1349).

Purely western is the peculiar story of Nicholas’s resurrection of three murdered boys. According to this tale, an innkeeper kidnapped and killed three youths. In the stained-glass window from Bourges Cathedral, they are shown reclining on a draped bed as the innkeeper raises his ax to kill them (Fig.4). At far right, Saint Nicholas extends his right hand in blessing toward the resuscitated boys, reflecting the legend’s account in which the innkeeper, having chopped up the boys, placed them in a barrel to cure. As an explanation for this, it is said that there was a famine during that year, and so the innkeeper was hoping to sell the cured meat as ham in order to make a living (sure, that makes total sense).

Figure 4. Saint Nicholas of Myra Resurrecting the three murdered boys, detail of a stained-glass window from the Chapel of Saint Nicholas, Bourges Cathedral (1205-1220)

The range of stories and miracles performed by Saint Nicholas developed with the saint’s reputation as a healer and the protector of children, unmarried girls, merchants, sailors, pawnbrokers and scholars. His popularity overall is reflected in the Index. Using the Work of Art Type filter, you’ll discover that because of this widespread cult, Saint Nicholas can be found in 169 manuscripts, and on 22 painted panels, 4 book covers, 2 miters, and 1 ring. Similarly, by browsing the Medium filter, we learn that there are 140 instances of depictions of Saint Nicholas in fresco, 37 in embroidery, 17 in mosaic, 15 in ivory, 8 in enamel, and 2 in niello.

It is only fitting that we should end with the death of Saint Nicholas, from whose remains a fragrant oil was said to flow, an oil that performed many miracles. But the story doesn’t really end here. Saint Nicholas’ body was stolen in the 11th century by Italian merchants and brought to Bari where it has been kept ever since. However, recent archaeological excavations in the church of Saint Nicholas in Demre (once known as Myra) have brought to light an intact tomb (soon to be opened) beneath the floor. Some believe this to be the original tomb of Saint Nicholas. If there’s a body in this tomb, does that mean that the relics in Bari are not of the saint after all?

We hope that by exploring images of Saint Nicholas in our database, you’ll also discover the many ways in which the new Index of Medieval Art can help you with your research. The database offers users the opportunity to expand and challenge previously acquired knowledge using new (still developing) filters that aid in narrowing the search thematically, iconographically, and stylistically. We have plans for other features as the beta continues to develop (though, not always as fast as we would like) offering new tools for discovery. And although this ongoing, expansive repository called the Index of Medieval Art does not hold all the answers, we hope that it will prompt you to ask more questions.

Maria Alessia Rossi, Kress Postdoctoral Researcher

As our regular readers know, the Index of Medieval Art recently launched a redesigned database. A challenging part of preparing for this event (codenamed Project Phoenix) was revisiting, reevaluating, and often revising how the Index has traditionally presented certain types of information. A century of accumulated data can reveal some unexpected things. Since the Index was founded in 1917, the history of the world has been…oh, let’s just call it “eventful.” Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the process of updating our outdated records as we upgrade the Index database has been a sobering reminder of all that has changed in the world, all that we have learned and achieved, and all that we have lost over the last one hundred years.

One set of data that made the need to revise our records very clear to us was the place names that we use. Obviously, names change, but we can point to a variety of reasons for the outdated information in the Index database. Some names in English are translations from the language of the place in question. In English usage, Wien remains Vienna, and Firenze remains Florence, but Lyon has superseded Lyons. Sometimes it’s a question of both language and script. What rules of translation and transliteration should we prefer? Depending on who is speaking or writing, a single place can be known by many names. For example, the Armenian place name Հռոմկլա can be transliterated as Hromkla, Hṛomkla, Hṛomklay, or Hrongla, but it can also be Rum Kalesi, Rūm ḳal‘esi, Rumkale, Qal‘ah Rumita, Qal‘at al-Rum, Qal‘at al-Muslimin, or Kela zêrîn. Can a single rule be applied consistently and make sense to users of the Index?

No matter the topic under discussion among the research staff at the Index, the answer to that last question turns out to be “no” frustratingly often. Language, like the rest of the world, is just too messy. One of our solutions, at least regarding how we handle locations, has been to embrace the messiness so that we simply have to account for complexity. So, when choosing an authority to cite for place names (authorities such as the Getty Thesaurus of Geographical Names and the Library of Congress, among others), we quickly decided that we need not cite the same authority in every case.

In addition to the problem of language, there are also outright changes of name that we have to recognize. The city of Byzantium has gone by a few different names in its history (Fig. 1). It’s called Istanbul now, but Istanbul was Constantinople. Now it’s Istanbul, not Constantinople. Believe it or not, that change became official many years after the Index was founded. It’s also worth mentioning that, although the name of that city should really be spelled “İstanbul” in Modern Turkish (with a dotted capital “İ”), the Index will continue to use the spelling familiar to English readers. Thus, even for something in situ, the database might list different names for an object’s or monument’s location of origin and its current location. Hagia Sophia is in Istanbul, but it was in Constantinople. (Have we given you an earworm yet?) Nevertheless, as we update the Index database, we will cross-reference place names so that, for example, a search for Istanbul (or İstanbul) will always also lead you to Constantinople.

But it’s not only names that change. Borders also sometimes shift. Once upon a time, when the Index was new, the city of Königsberg was in Prussia. After World War I, Königsberg was part of Germany (the Weimar Republic, that is, and then Nazi Germany), and by the end of World War II, much of the city had been destroyed, including museums and medieval monuments. That makes Germany the last known location for those buildings and the objects they contained (Fig. 2). Once the Prussian home of Immanuel Kant, Königsberg is now within the Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland. And, oh yes, it’s called Kaliningrad now. Our goal at the Index of Medieval Art is to continue to update our database to account for such changes.

By the way, for those of you as interested in topology as you are in topography, Kaliningrad was—when it was Königsberg—the subject of a famous logic puzzle. The city straddles the Pregel River, and there are two islands in the river, a feature reminiscent of Paris. The islands in Königsberg were connected to the rest of the city, but the bridges were configured in such a way as to give rise to this puzzle: “Can you walk through Königsberg crossing each of the seven bridges only once?” This puzzle has rules, of course: you have to cross each bridge only once, and you must cross each bridge completely (without turning around in the middle), but you may not cheat with a boat or hot air balloon. The puzzle was solved in the 18th century by Leonhard Euler, the great Swiss mathematician and general smarty-pants. When it comes to walking through Königsberg, crossing each of the seven bridges only once, Euler proved that…spoiler alert…it couldn’t be done!

Time does things to maps. Not only do place names change and frontiers shift, but cities rise and fall, roads are rerouted or renamed, and buildings are razed or rebuilt. Sometimes new bridges replace old ones, so that even that famous logic puzzle about the seven bridges of Königsberg has been affected by the last two centuries of human history. Only two of the bridges that Euler knew still exist, and the new configuration of bridges means that the Königsberg puzzle is no longer a puzzle at all in Kaliningrad!

On a related note, have you ever wondered, “When is a map not a map?”

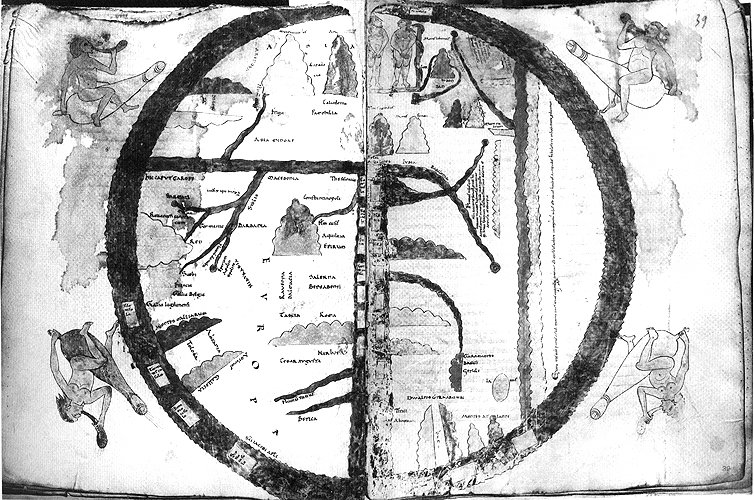

More precisely, the question that arose recently at the Index was this: “When is a map a map, and when is it a representation of a map?” Questions like this one can lead to surprisingly lively discussions at the Index of Medieval Art. This particular question came up while we were discussing how the Index ought to categorize certain subjects. It seems clear that some things are maps, like the Hereford Mappa Mundi. It also seems clear that some images include representations of maps, without actually being maps (Fig. 3).

However, some cases may be less clear, like a map in the Turin Beatus (Fig. 4). Is this an illumination that consists of a map, or is it a representation of a map? In other words, when is an object a map, and when is “map” the subject of an image?

What we at the Index sincerely hope is that you, everyone who uses the Index, will join us in addressing such questions. We invite subscribers to try out the Project Phoenix beta to see what we’ve been working on. We welcome your thoughts, so please tell us about your experience using the database, or share your observations about how we handle the content. Please bear in mind that this is the beta stage of development, so not everything is working perfectly yet. Some features have not been fully implemented, and some may be disabled from time to time while we work to improve them. It will also take us some time to edit the contents of the database so that everything is handled consistently within our revised format. In the meantime, the old, familiar database is still available to subscribers, and it will continue to be available until we are confident that the new version can supersede the old one.

We look forward to hearing from you. Your insights and feedback will continue to be vital to the success of this enterprise, just as they have been through the first 100 years of the Index of Medieval Art.

Henry Schilb

The Index invites paper proposals for two sessions at the 2018 Medieval Congress in Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, on the theme of “Iconography and Its Discontents.”

Modern scholars often express discomfort with the term “iconography,” caricaturing its study as obsessed with rigidified taxonomies, elaborate stemmae, and the abstract pursuit of textual analogues for free-floating images. Yet the fundamental questions that drive iconographic studies remain central to scholarship in art history and many other medievalist disciplines. What did a medieval image mean, and to whom? How did these meanings change in different contexts and in the eyes of different viewers, and what can this tell us about the values and practices of the society in which they were made and viewed? The ways in which researchers answer these questions, meanwhile, has changed dramatically, bolstered by new methodologies and the increasing availability of digital tools to quantify, compare, and analyze a wide range of medieval images. Such advances suggest that the study of iconography not only is “not dead yet,” but is very much alive and open to reassessment.

Our two sessions capitalize on the new vitality of current iconographic studies by gathering papers that reexamine the potential of iconographic work for medievalists, prioritizing work that pushes past traditional approaches to engage with the new questions, new methods, new disciplines, and new technologies of greatest impact within the field. Following on the centennial and digital relaunch of Princeton’s recently renamed Index of Medieval Art, one of the first and longest-lived iconographic repositories of its kind, the session aims to chart a new path in a scholarship transformed by both technological advancements and disciplinary creativity.

Session I: Iconography and/as Methodology. What questions do today’s scholars ask of medieval images, and what approaches do they take to answering them? Do their efforts represent a break with the past or a continuation of it? What disciplines do they most engage? For this panel, we invite papers that explore the impact of new methods, whether from art history or from other disciplines, on modern understanding of how medieval images did their work for their makers and viewers. Papers that assess the relevance or revision of past approaches are also welcome.

Session II: Iconography and Technology. How have digital resources transformed the ways in which scholars approach the study of medieval images and their meaning? What new questions (and answers) are now possible, and what remains the same? For this panel, we seek papers that evaluate the impact of online collections, databases, and other digital tools on image-based scholarship in any discipline. Both case studies and broader analyses are invited.

Proposals are invited from scholars at all levels and in any relevant discipline. To submit, please send a Participant Information Form (https://wmich.edu/medievalcongress/submissions) and one-page abstract to:

Pamela A. Patton, Director

Index of Medieval Art

A7 McCormick Hall

Princeton University

Princeton, NJ 08544-1018

Zacharias writing John’s name at his nativity, Missal of Eberhard von Greiffenklau (Walters MS W. 174, fol. 191r)

Over the next few weeks, friends and users of the Index will see signs of our gradual shift to a new name, The Index of Medieval Art. This revision was undertaken after careful thought and consultation with Princeton faculty, students, administration, and the wider scholarly community.

The change reflects the broad evolution of our institution’s scope and mission since its founding in 1917, when its work was limited to cataloguing religious themes and subjects in early Christian art up to 700 C.E. A century later, our records have expanded to encompass both religious and secular imagery, including Jewish and Islamic works, from the first centuries of the Common Era until the sixteenth century. The scholarly activities that we support and generate have also evolved over the years, reflecting the broad interpretive and interdisciplinary analysis that has become fundamental to the study of medieval images. Our new name signals more accurately our expanded holdings, mission, and goals, as well as our institution’s broad potential to serve researchers in multiple fields of study.

If you have already bookmarked our Facebook and Twitter accounts using their original URLs, you’ll be redirected to the correct ones and shouldn’t notice an interruption. The new URLs for the sites appear below. In the coming months, we will also implement new URLs for this website and our redesigned database, which is set to launch in September 2017. We look forward to sharing news of those changes with you soon!

Facebook: www.facebook.com/imaprinceton/

Twitter: @imaprinceton

From the Gospel of Matthew, 27:62-66, Douay-Rheims: And the next day…the chief priests and the Pharisees came together to Pilate, saying: Sir, we have remembered, that that seducer said, while he was yet alive: After three days I will rise again. Command therefore the sepulchre to be guarded until the third day: lest perhaps his disciples come and steal him away, and say to the people: He is risen from the dead; and the last error shall be worse than the first. Pilate saith to them: you have a guard; go, guard it as you know. And they departing, made the sepulchre sure, sealing the stone, and setting guards.

Of the four Evangelists, Matthew alone records the above conversation among Pilate, the chief priests and the Pharisees, the latter two being concerned that Christ would emerge from the tomb to continue stirring up the people. To which Pilate responded, well, then guard the tomb. He had already washed his hands of the matter, yet here it is again. So, just guard the tomb, and (reading between the lines) leave me out of it. This episode also appears in the apocryphal gospel of Peter, where the story follows the same thread.

1. Miscellany, 1280-1299, Cambridge, St. John’s College, MS K.21. The upper image shows two high priests or Pharisees before Pilate expressing their concern that the tomb be guarded. Below, Christ stands in a sarcophagus; three soldiers sit in front of it. The text in the left column relates the story.

Christ’s resurrection appears in the Index of Christian Art 500+ times in multiple media; the order to set the guard is represented only sixteen times. The Cambridge Miscellany (Fig. 1) presents the thread of the story well, with the text in the left column, and in the right, a miniature with two figures petitioning Pilate, above a resurrection image with soldiers.

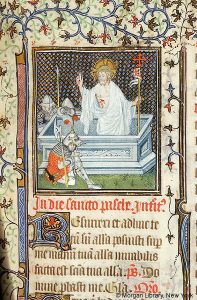

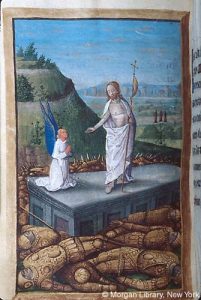

2. Châlons Missal, c. 1400, New York, Morgan Library, MS M.331, fol. 130r. Three soldiers surround a sarcophagus, one leaning on the back side of the tomb.

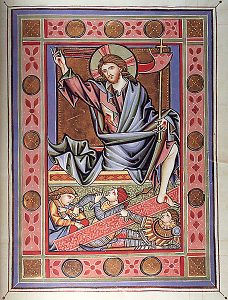

3. Hours of Anne of France, 1470-1480, New York, Morgan Library, MS M.677, fol. 200v. Many recumbent bodies wearing gold armor surround the tomb.

The number of soldiers present varies. Two, three or four are common (Fig. 2); examples exist with what appear to be small armies (Fig. 3).

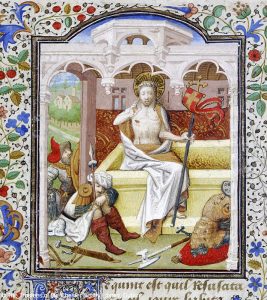

4. Rheinau Psalter, c. 1250 Zurich, Zentralbibliothek MS Rheinau 167, fol. 107r. Three soldiers, with eyes open, two looking up at Christ, one pointing toward him.

Largely the soldiers are sleeping, but some are awake, looking up toward the risen Christ, sometimes shielding their eyes (Fig. 4).

5. Coëytivy Hours, 1440-1449, Dublin, Chester Beatty Library MS W.82, fol. 342v. A soldier with his back turned rests comfortably on a red bolster with a gold tassel.

They wear chain mail or armor that is medieval, not Roman, which they would likely have been. Many are accompanied by weapons and shields, sometimes decorated with quasi-heraldic ornament. Some have creature comforts, such as a bolster to sit on, or a mattress to lie on (Fig. 5).

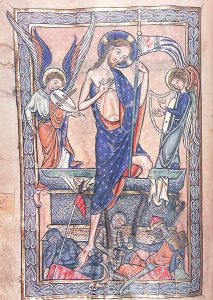

6. Antiphonary Fragment, c. 1300, Philadelphia Free Library MS Lewis EM 44.15. Christ steps from the tomb onto the neck of a sleeping soldier.

They pass the night at the tomb; they sleep even though Christ occasionally steps on them while climbing out of the tomb (Figs. 6 and 7); and they are still asleep when the three Marys, or Holy Women, arrive the next morning carrying ointment jars and sometimes censers.

7. Missal of Henry of Chichester, c. 1250, Manchester, John Rylands University Library, MS lat. 24, fol. 152v. Christ steps on one of two dark-skinned soldiers asleep before the tomb.

Signs of “otherness” appear: a distorted face with a pig-like snout for a nose; knotted headdresses; curved swords or scimitars; dark skin (Fig. 7). The tomb itself may be a plain sarcophagus; or it may look more like a medieval shrine, with openings in the base.

8. Psalter, c. 1290, New York, Morgan Library, MS M.34, fol. 187v. Each of three soldiers is tucked into an opening below the tomb.

Instead of pilgrims trying to get closer to the relics inside, the soldiers use those openings for cozy sleeping spaces (Fig. 8).

Judith K. Golden

On May 19-20, 2017, international and US Scholars will gather at Princeton to examine the near-intact monastic treasury of San Isidoro in Leon, in northern Spain, as a springing point for larger questions about sumptuary collections and their patrons across Europe and the Mediterranean across the Middle Ages. Topics of inquiry include Islamic law and sumptuary production, Christian manuscripts and metalwork, patronage and royal studies, identity and gender studies, and cultural and political history. The diversity of questions and perspectives addressed by the speakers will shed light on the nature of Leon as a paradigmatic treasury collection, as well as on the broad efficacy of multidisciplinary study for the Middle Ages.

Follow the link below for a full schedule and (free) registration information. We hope to see you there!