Are you familiar with the popular iconography of the saint whose feast day falls on April 23? If you’ve ever been to an English pub, you probably are, even if you didn’t realize it! According to medieval legend, Saint George of Cappadocia was the third-century saint and martyr who slew a dragon. Usually, George is represented as a knight mounted on a horse. Sometimes shown carrying a cross-inscribed shield, his red and white armorial attribute, he thrusts his lance into the jaws of the dragon under his horse’s hooves.

George’s heroic posture was modeled on the iconography of other saints and mythological figures. Theodore Tyro and Demetrius of Thessalonica, for example, also slew beasts in the name of vanquishing evil. Carrying talismanic or protective power for people threatened by worldly dangers, dragon-slayer images decorated many small, portable objects, including ampullae, lamps, carved gems and small plaques from the late antique, Byzantine, and Coptic worlds.1 Building on narratives of his heroism, tales of George’s life and deeds spread throughout medieval Europe with Crusaders returning from the East. By the high Middle Ages, the Golden Legend, a compilation of saints’ lives by Jacobus de Voragine, fleshed out the life of George with a rescue narrative of a king’s daughter and inspired numerous visual representations in different media.2

Depictions of the rescue legend, which follow standard iconography for George’s slaying of the dragon, often insert the princess as a minor character of relative insignificance. But is she insignificant? Traditionally identified as a third or fourth century Komnenian princess of Trebizond, she is sometimes named Sabra or Cleodolinda (or Cleolinda, Cleudolinda) (Fig. 1). According to the legend, the princess was weeping profusely, anticipating her certain death as the next human sacrifice to the dragon, when George arrived at a town called Silene in Libya. He pledged to help her, and he rode toward the dragon with his sword drawn.3 In swift succession, George pierced the dragon and the princess bound her girdle around the beast’s neck. She led it back to the townspeople alive which brought about the people’s mass conversion to Christianity.

In some earlier depictions of the legend, the princess appears with prominence, including on a Romanesque capital from a monastery in Saint-Pons-de-Thomières now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the capital face, the princess wears a long dress, props one hand on her hip, and extends a flower toward George (Fig. 2). Around the other side, George kneels behind his shield, trailing a coiled serpent that approaches the princess from behind. Her thank offering to George in the midst of his attack on the dragon suggests that there will be a good outcome despite the violence surrounding her.

In another Romanesque capital from the abbey of Saint-Pierre of Airvault in Poitou, the princess stands behind George, although he rides away from her, effectively separating her from the dragon’s reach (Fig. 3). With George exiting left, the princess becomes a key figure of interest to viewers gazing upward at the capital. Here, she maintains a stoic stance, and, in ironic juxtaposition with the nearby head of a menacing grotesque, her arms are crossed over her body in a way that suggests patience and perseverance in the face of danger.

By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the iconography of the princess and her role in George’s slaying of the dragon were handled with more flexibility, especially in manuscript illumination.5 Some examples, such as the Hungarian Angevin Legendary, illustrate the narrative more literally, showing the princess tethering the dragon or leading it away by its makeshift leash (Fig. 4). In this variant of her iconography, the Princess of Trebizond is actively engaged with George’s feat and secures the dragon in one forceful pull.

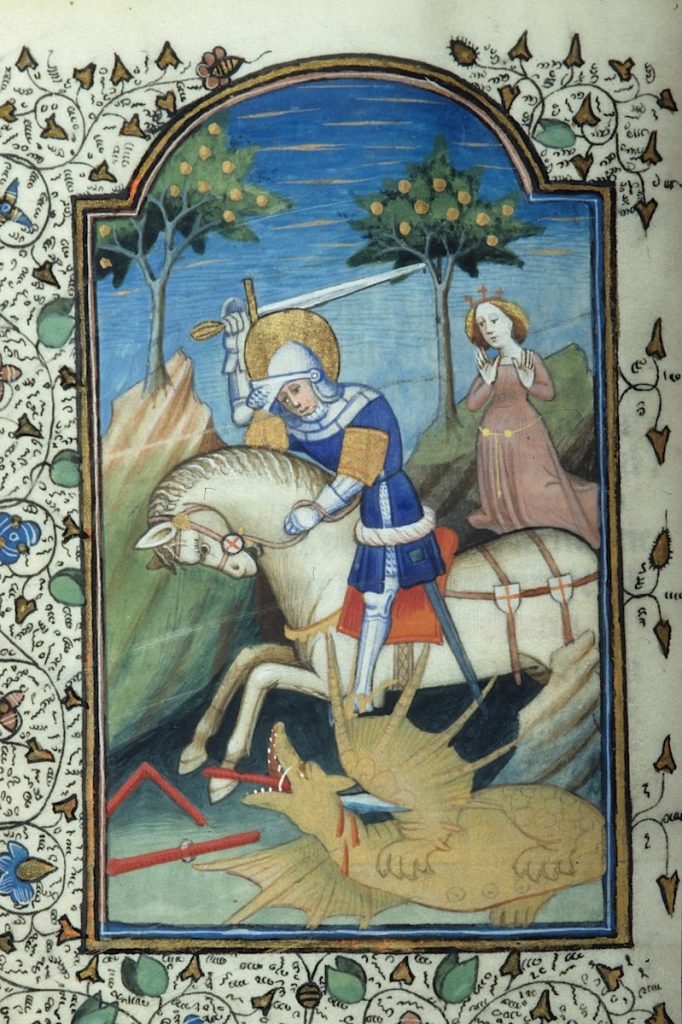

At George’s suffrage in illuminated prayerbooks, especially in Books of Hours, the princess often appears behind the slaying scene, kneeling in prayer, and protected a distance.6 But in some of these late medieval depictions, she tends a flock of sheep, sometimes holding one sheep on a lead, or she simply raises her hands in surprise at George’s victory (Fig. 5).7

In all these images, the princess functions as more than a mere attribute of George. Instead, she is actively reimagined as part of the narrative. Artists creatively customized their images of Georgian legend to not only explore the princess’s instrumental role in her rescue but to highlight her intercessory function in saving the townspeople–in a literal sense and by their newfound faith. Whether showing her as prayerful, gracious, surprised, or tethering the dragon, the iconography of the princess offers a versatile model of female agency, one that likely inspired her viewers.

We can find echoes of such rescue narratives in other ages and media. If you have played the classic Super Mario Bros. video game, then you know the game’s mission: rescue Princess Peach! As aficionados know, the eighth and final world of the game culminated in an underground battle with Bowser, the hammer-hurling, spiky-shelled antagonist (Fig. 6). If you hurled enough fireballs back at Bowser, he overturned and descended into an abyss off screen, allowing Mario to advance over the bridge and reach the princess on the other side. Much like the Princess of Trebizond, Princess Peach had to be rescued, and she, too, has been reimagined over time: her characterization within the Nintendo empire of games and films eventually evolved from damsel in a dungeon to a fighter in her own right.8

You can still find the iconography of George slaying the dragon in the modern world, often in a reduced composition of equestrian, saint, and dragon. Once you know what you’re looking for, you’ll spot George in any number of settings, especially on pub signs like the one on my local haunt when I was a grad student in London (Fig. 7). Whether under his sign or not, those who cheer to Saint George today would do well to remember this: once upon a time, a princess filled with purposeful character also conquered a beast.

Thank You, Saint George! Your Quest is Over.

Appendix

The Index subject files provide a starting point to locate examples of the Princess of Trebizond in the six works of art:

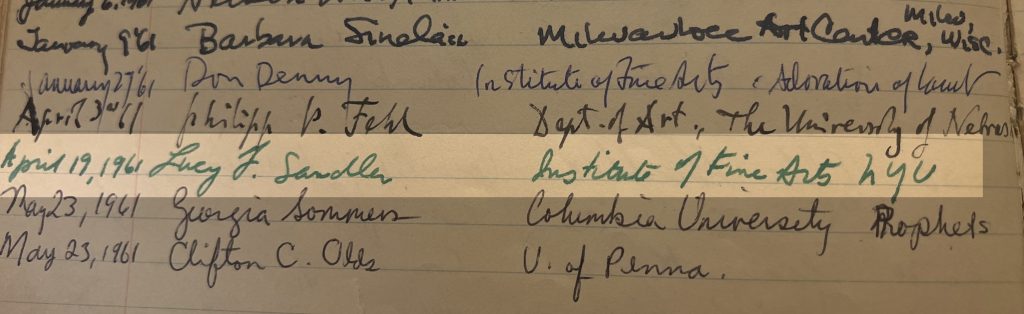

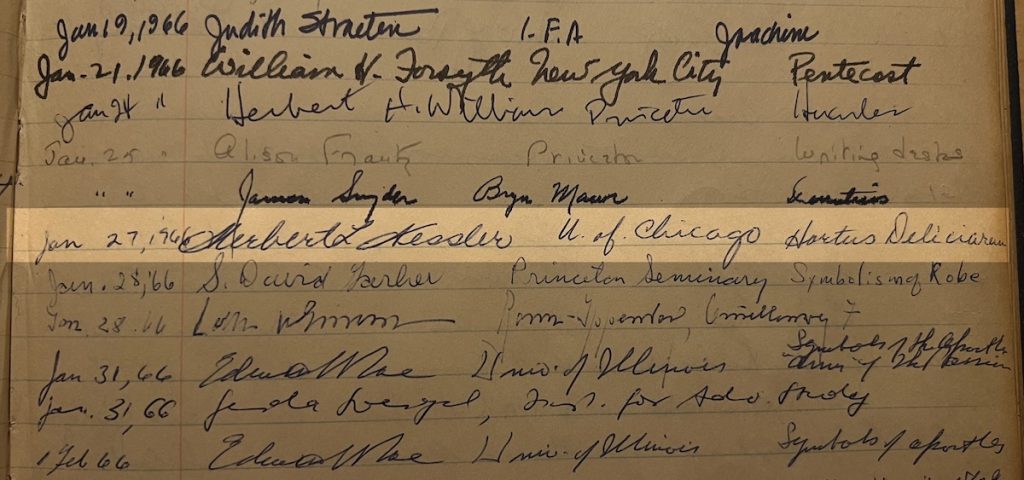

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections and warmly thank Lucy Freeman Sandler, Professor Emerita, Institute of Fine Arts of New York University, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I began to study painting at Queens College but my first undergraduate art history course focused my interest in a new direction, and, inspired by a charismatic medievalist, Frances Godwin, I decided to study the art of the Middle Ages on the graduate level. On Prof. Godwin’s advice I applied to and was accepted at Columbia University and took courses with Meyer Schapiro, a formative intellectual experience, and then with John Plummer, who was then himself completing a Ph.D. with Schapiro. It was Plummer’s course, called “Gothic Painting,” which was primarily about illuminated manuscripts, in which I “discovered” marginal illustrations, a topic that became the subject of my master’s thesis. For my own Ph.D. I transferred to the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University (they generously awarded me a scholarship), eventually completing a dissertation on the Psalter of Robert de Lisle (London, British Library, Arundel MS 83).

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

I cannot remember the date of my first visit to the Index, which Index records indicate was 1961, during the time I was working on my dissertation. I have certainly used the Index many times since, and have known all its directors since Rosalie Green, although, to my regret, I did not meet her.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

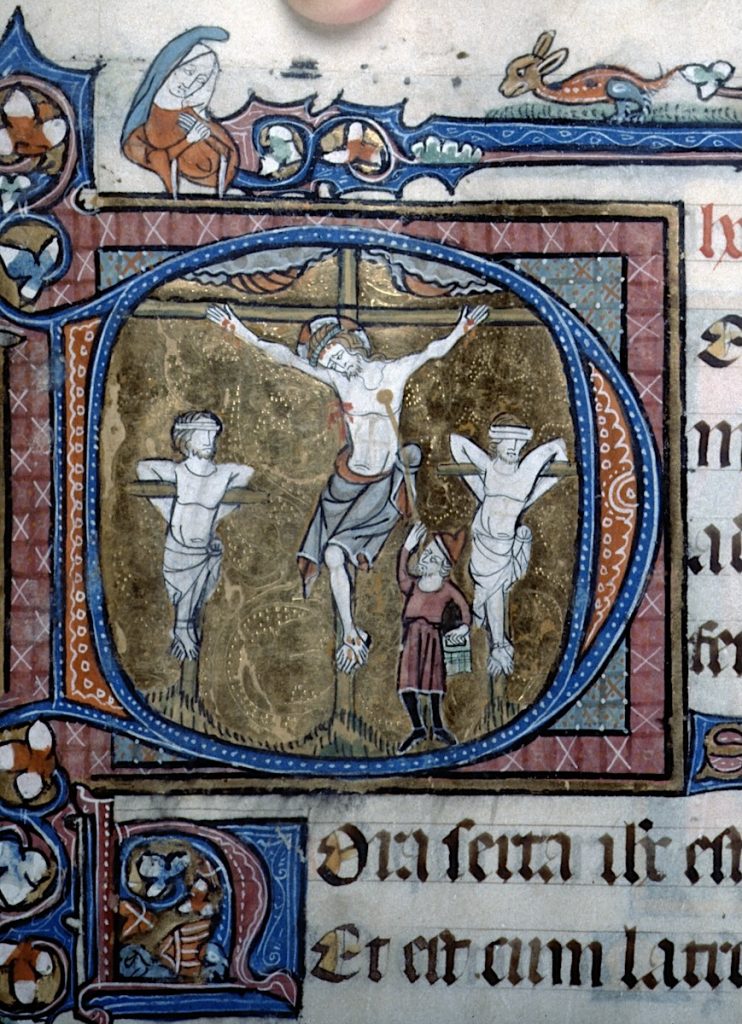

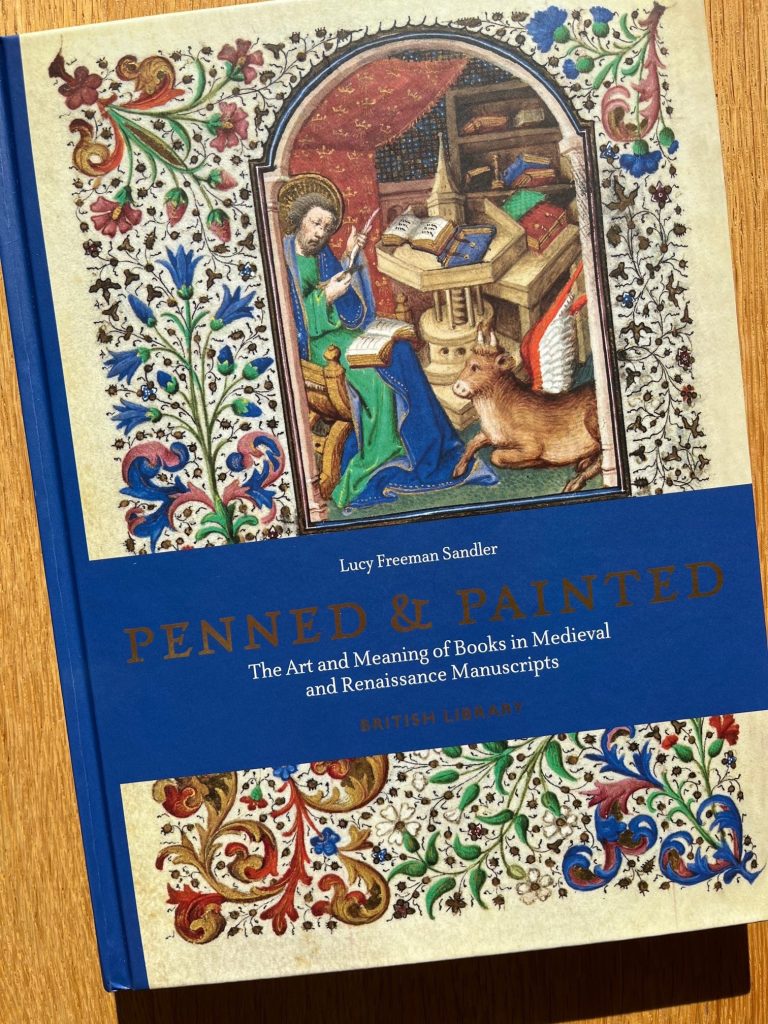

I remember at least one visit, probably sometime between 1961 and 1964, when I was trying to determine the date during the Gothic period at which the crossed feet of the Crucified Christ changed position. I must have looked at hundreds of photos of every late thirteenth and fourteenth century Crucifixion at the Index. I can’t say that I came to any definitive conclusion but I certainly learned a lot about Crucifixion representations. I have found the online version of the Index invaluable, especially in connection with my latest book, Penned & Painted: The Art and Meaning of Books in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts (London: British Library, 2022), for which I did much of the research during Covid.

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I have attended quite a few Index conferences and have spoken at several, including “The Weingarten Office Lectionary and Passionale in New York and St. Petersburg,” in Romanesque Art and Thought in the Twelfth Century in Honor of Walter Cahn (October 2006); “One Hundred and Fifty Years of Study of the Illuminated Book in England: The Bohun Manuscripts from the Nineteenth Century to the Present,” in Gothic Art & Thought in the Middle Ages: A Conference in Honor of Willibald Sauerländer (March 2009); “The Bohun Women and Manuscript Patronage in Fourteenth Century England,” in Medieval Patronage: Patronage, Power and Agency in Medieval Art (October 2012); and “Princeton Garrett MS 35 and Homeless English Gothic Manuscripts,” in Manuscripta Illuminata: Approaches to Understanding Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts (October 2013). All these were subsequently published under the editorship of Colum Hourihane. I also contributed a tribute to John Plummer: “John Plummer: A Reminiscence,” in Between the Picture and the Word: Manuscript Studies from the Index of Christian Art, ed. C. Hourihane (University Park, PA, 2005), 9–11.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As co-editor of the Index-based Studies in Iconography, from 2009–2015, I hoped to serve the mission of the journal, as it has continued to the present, to publish “innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed.”

Thank you, Lucy! As the home for Studies in Iconography we’re committed to publishing innovative work in iconographic studies, and we’re grateful for your invaluable contributions to the Index over so many years.

The Index is pleased to announce the launch of a new digital resource for the study of Byzantine iconography, the Lois Drewer Calendar of Saints in Byzantine Manuscripts and Frescoes. Compiled by the late Lois Drewer, PhD, longtime specialist in Byzantine art at the Index, this calendar identifies saints, cites standard and hagiographic references (with a guide to their abbreviations), and concisely describes manuscript illuminations and frescoes. The calendar is organized by feast days in the Constantinopolitan calendar.

There are four main ways to browse the resource. The first is by selecting a month and day under the tab for calendar. This entry point leads to the core of the data, and we recommend this as a good place to start. For example, searching today’s date of the fifth of March reveals three entries for saints: 1. Mark of Egypt; 2. Conon the Gardner; and 3. Hypatius of Gangra. The list you will find there offers identifications, references, and examples.

Many of the saints and holy martyrs included in Dr. Drewer’s calendar are obscure or infrequently represented in medieval art, such as Conon the Gardener (also known as Conon of Perga), a gardener from Nazareth martyred under the Roman emperor Decius (r. 249–251 CE).[1] In some cases, the iconography has not yet been cataloged by the Index, making this an especially useful additional resource.

There are also two lists for iconographic motifs and iconographic scenes with feast days linked on the right, and a list of feasts days organized A to Z. The iconographic motifs and scenes are grouped alphabetically beneath bold headings.

A majority of the headings in this resource cover martyrdom and torture scenes for Byzantine saints–among them holy martyrs, hermits, prophets, and women, but Drewer also included groups for various vestments and clothing, human gestures, attributes, and objects. For example, it is possible to see that an axe is associated with John the Baptist.

In some examples of medieval iconography, the preaching John the Baptist is depicted pointing to an axe at the base of a tree, a reference to Matthew 3:10. Or you can discover that the representation of grief is linked to Sophia of Rome, who is portrayed in various scenes as mournfully throwing out her arms in response to the beheadings of her daughters Pistis, Elpis, and Agape.

There is much to discover by browsing these lists, and we expect that this resource may usefully supplement your searches within the wider Index of Medieval Art Database. You may also try browsing the Svetlana Tomeković Database of Byzantine Art for similar themes represented in Byzantine art. We welcome your feedback, and we look forward to receiving questions through our research inquiries form.

We warmly thank the Index’s Technology Manager Jon Niola for bringing this project to fruition. Lois Drewer dedicated much of her life to iconographic research, and we feel certain that she would have approved of this posthumous tribute. We are proud to offer this additional resource so that all may benefit from Dr. Drewer’s calendar of saints.

[1] Drewer’s database notes three instances of the iconography of the holy martyr Conon the Gardener: a small illustrated Menologion, 1322-1340 (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. f. 1, fol. 30v), and two frescoes in the south aisle of the narthex in Dečani and in the dome of the south tower narthex in Treskavec, all of which have yet to be added to the Index database.

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and we warmly thank Herbert Kessler, Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins University and Index friend, for his time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

After studying medieval art as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, I completed the MFA and Ph.D. at Princeton. At UC, Margaret Rickert had inspired me to become a medievalist; she was also Rosalie B. Green’s Doktormutter, so Rosalie and I had a special bond from the start. I continued to use the Index at Dumbarton Oaks when I was a Fellow there in 1965–66 and then, again, when I returned to Princeton as a Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in 1969–70.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

RBG1 oriented all new graduate students, so 1961. The Index was then in the Neo-Gothic Cram wing of the original McCormick Hall. Graduate students had keys and used it steadily, especially as a picture resource. The Index staff felt under-appreciated and with good cause: though RBG and Isa Ragusa were distinguished and consistently professional and helpful they knew that the faculty did not respect them as scholars. When I was being recruited to the University of Chicago faculty in 1965, the Dean offered to acquire a copy of the Index for me (because William Heckscher, who had been offered the position earlier, had asked for one), but nothing came of that. As computers were evolving in the 1980s, the Getty Center hired two young persons to recommend ways in which the Index might be digitized. Things did not go well, and I was sent (from Johns Hopkins) to reconcile the Index staff with the Getty interlopers. During the discussions, we all realized how the new technology might allow the Index to be modified in ways better to serve other disciplines, especially e.g. by refining types of musical instruments, botanical and zoological species, or agricultural implements.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I have never used the Index for teaching and, frankly, cannot remember a single eureka moment while using it (except, of course, finding a picture I did not know).

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I gave papers at Iconography at the Crossroads2 and Romanesque Art.3 Both were very important gatherings and publications.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As recently as twenty years ago, one of my own graduate students brushed away an argument with “That’s only iconography,” “Only” was the operative word there. In the wake of the material turn, decolonial turn, global turn, historiographic turn, experiential turn, the ornamental turn, . . . . , searching for texts that identify medieval subjects is no longer sufficient. And with the Patrologia Latina and other compendia online, it is not even fun. Simply to dismiss iconography, however, is ignorant. As I myself have argued at length in a recent essay, “the interweaving of text and image and the sensual pleasure of [medieval art’s] color and rich materials” was the essence of medieval art.4 Iconography is therefore destined to remain a fundamental instrument for studying it.

Please join us and register for the next virtual database tutorial with the Index on Tuesday, March 25, 2025 from 12:00 – 1:00 pm EST.

Read more about it at this link: https://ima.princeton.edu/index_training/.

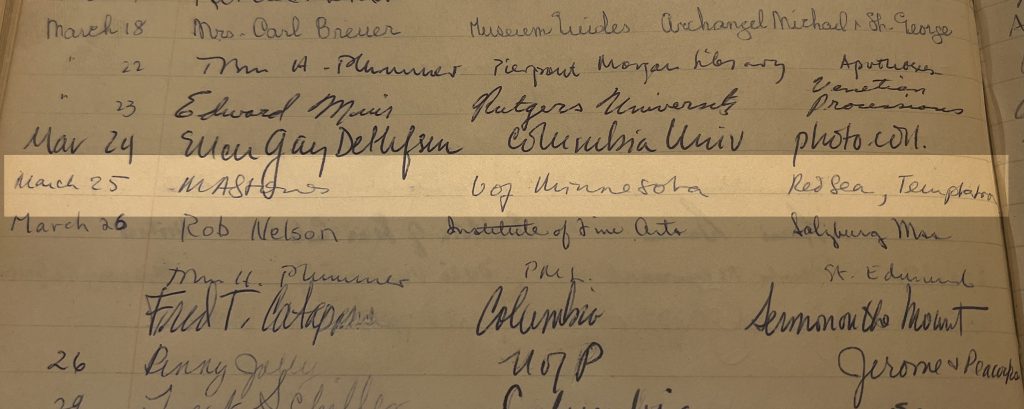

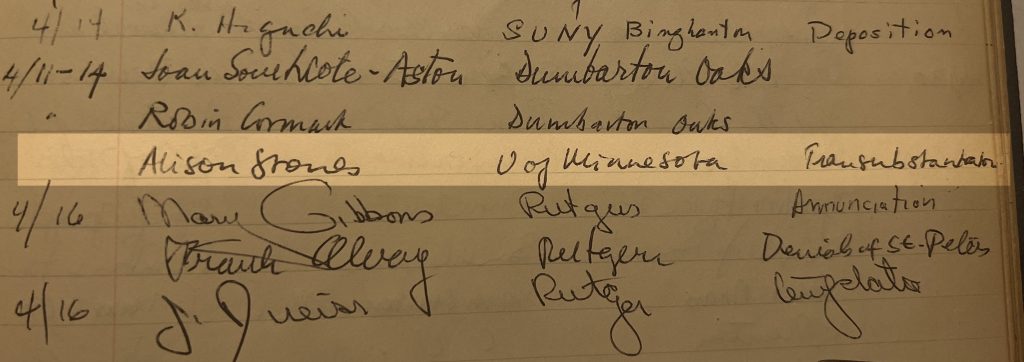

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank Alison Stones, Professor Emerita, University of Pittsburgh, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

In the Fall of 1969, I emerged as a not-quite Ph.D. from the Courtauld Institute (that happened a year later in December 1970/January 1971) to begin what would turn out to be a life-long academic career in the United States. My academic background was in French and German literature, followed by a medieval art and architecture specialty at the Courtauld where I worked with the inimitable Christopher Hohler, and with David Ross at Birkbeck, with musicology from Ian Bent at King’s and Heraldry with Nick Norman at the Wallace Collection.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

By 1969 I already had many friends in the US, notably Adelaide Bennett at the Index, Paula Gerson then at Fordham, James Marrow at Binghamton, and Bob Deshman at Toronto, Canada. All of them had worked alongside me in London, so the transition to the US was easy for me and all of them made me feel welcome there. The Index, under Rosalie Green, was among my first stopping places and continued over the years to be a haven for my research on French illuminated manuscripts, from the days of the invaluable old card system up to the new innovations of the 21st century. Adelaide and I would argue back and forth over the limitations and benefits of “Index-Speak” which invited us to hone our descriptive (and analytical) skills, and more recently it was a pleasure to encounter my former student Judith Golden among the ranks of the Index staff. One simply learned so much there!

Under Colum Hourihane came the era of the Index conferences, not-to-be missed sessions of innovative research, captured with regularity in the impressive series of publications produced under his editorship. I was privileged to attend many of these conferences and to participate in Iconography at the Index: Celebrating Eighty Years of the Index of Christian Art (1997),[1] Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus (2004),[2] as well as the festschrift volume Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer (2017).[3] Naturally, these essays all depended heavily on research conducted at the Index, where I must admit that my preference was still the old card system rather than the new, online version. Thankfully, the Index conferences are ongoing, and now available online with a livestream link. From the presentations to the interaction that follows, one learns so much!

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database over the last three decades? Where do you think Index work should go next?

As to future directions for the Index, I wish it could become a repository for the many online medieval databases (my own included) that risk becoming defunct once their creator retires. I appreciate the logistical issues and the problems of different software, but so much creative work is out there, and risks being lost. This in addition to the very valuable repository of information and images that make the Index such an indispensable tool for all medievalists. Long may it continue to flourish and many thanks for all I have learned there!

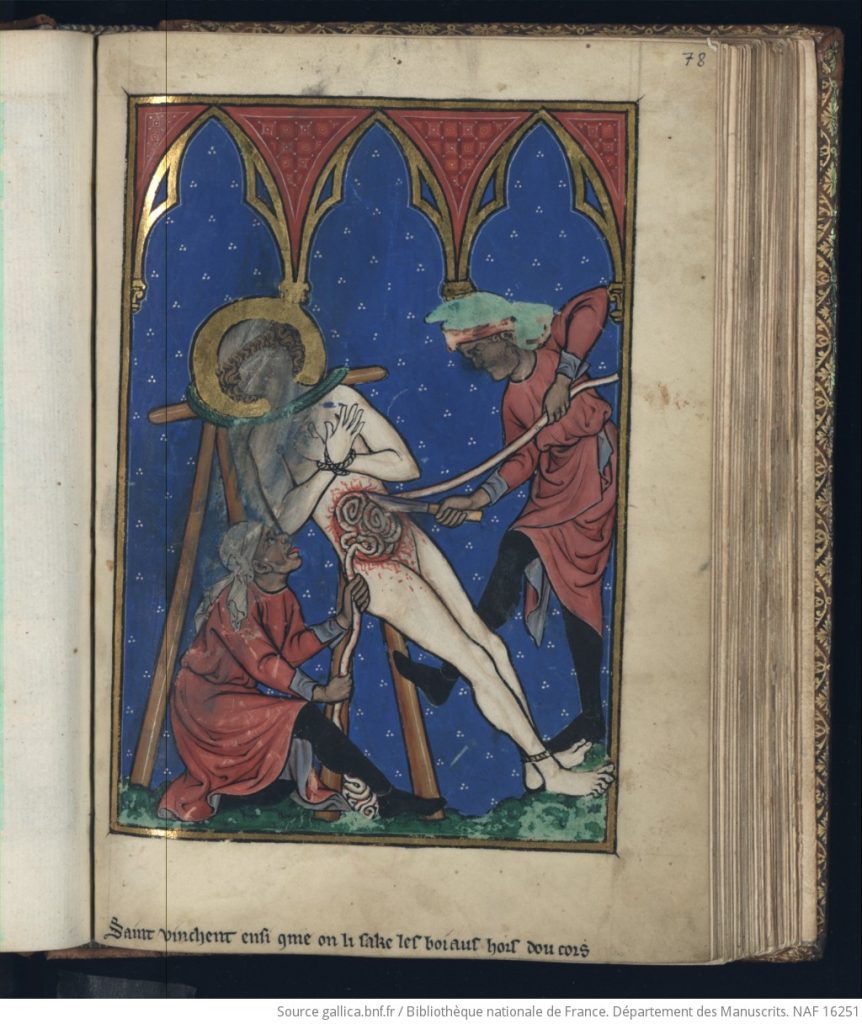

[1] Alison Stones, “Nipples, Entrails, Severed Heads and Skin; Devotional Images for Madame Marie,” in Image and Belief: Studies in Celebration of the Eightieth Anniversary of the Index of Christian Art, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 1999), 48–64.

[2] Alison Stones, “Questions of Style and Provenance in the Morgan Picture Bible,” in Between the Picture and the Word: The Book of Kings (Morgan 638) in Focus: A Colloquium in Honor of John Plummer, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Department of Art & Archaeology and Princeton University Press, 2004), 112–121.

[3] Alison Stones, “Tobit: A Recently Rediscovered Cutting from the Brussels-Rylands Bible,” in Tributes to Adelaide Bennett Hagens: Manuscripts, Iconography, and the Late Medieval Viewer, eds. Pamela A. Patton and Judith K. Golden (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2017), 335–353.

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2024.

Although some scholars have claimed to see something like pizza in a wall painting at Pompeii, most historians trace the origins of modern pizza to sixteenth-century Naples. However, researchers at the Index of Medieval Art have discovered previously unrecognized medieval evidence of pizzerias in manuscripts dating at least two centuries earlier.

These early pizza-making scenes depict workers baking crusts, as in the miniature of a fifteenth century Book of Hours (Princeton University Library, MS Garrett 54). Notice how the pizza chef thrusts a long-handled peel with a round crust into a roofed pizza oven. Other steps in the preparation of crust have been identified in the iconography of pizzerias, including a hybrid figure tossing a circle of dough into the air to give the pizza its custom shape. Tossing dough in the air has long been the preferred method in pizza preparation to thin out the crust and give it its signature stretchy, glutinous finish.

Our research found that the toppings for pizza throughout the medieval period would have run the gamut. The typical meats and vegetables that popularly eaten today would have featured on pizza in the Middle Ages, too…with one major exception: the edible berry of the plant Solanum lycopersicum, more correctly identified as the Amoris pomum and commonly called the “the tomato.” Tomato sauce on pizza was strictly prohibited due to the prevalence of the belief that the love apple is the devil’s fruit. But pizza was always a highly customizable dish, and pizza mongers were apt to use any combination of sauces with any number of toppings to suit their palates. Pineapple and anchovies on pesto with casu martzu was a particular favorite among both penitents and unrepentant heretics alike.

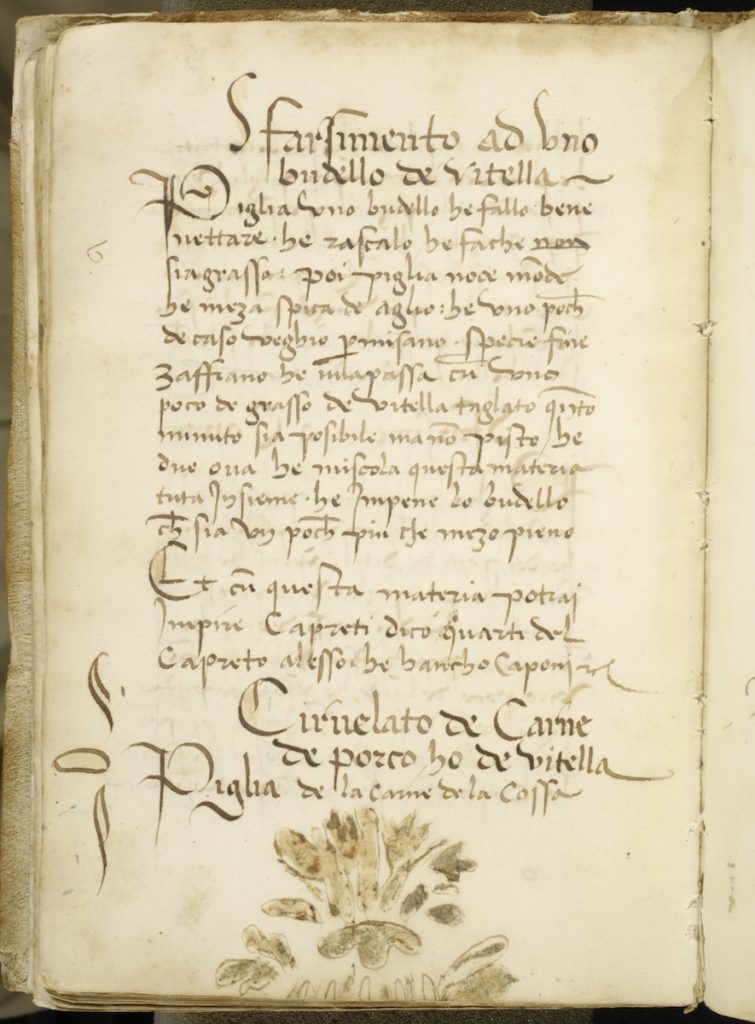

You can imagine our surprise at finding in one late fifteenth-century Neapolitan cookbook, known as the “Cuoco Napoletano,” a recipe for a type of blood sausage known as cervellato (manuscript inscribed “Cirvelato de carne de porco ho di vitelli”) with a mention of its use in pizza preparation. Legendarily, and much like today, sausage was a favorite topping among medieval consumers of pizza, and the following leaf in the cookbook describes such usage in great detail. Or are you a fan of fungi on your pies? Mushrooms too made it onto the menus of pizza chefs, and some illustrations in medieval manuscripts show the fleshy morsels lined up and ready to chop.

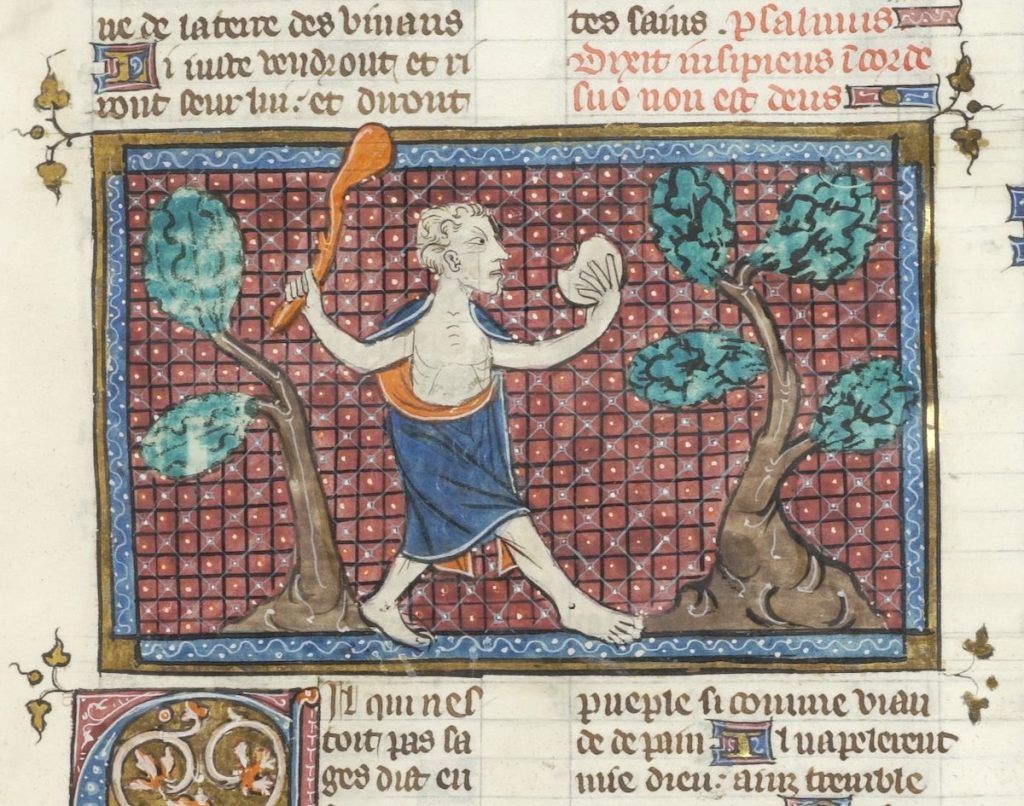

Whether deep-dish or thin with extra cheese, pizza was prized in the Middle Ages. Pizza to go wasn’t out of the ordinary, either, but the pie would have to be fiercely guarded by its consumer. Eating a slice, or “wolfing ’za” as the medieval collegiate vernacular would have it, was often a perilous, two-handed operation. In one medieval image, you’ll notice that a large man chowing down on a delicious slice folded in one hand was required to wield a club with his free hand to ward off would-be pizza poachers!

It was also a seasonal favorite. Such early forms of a pizza would have been regarded as the perfect addition to any menu on the first day of April.

(And by the way, April Fool!)

We are very pleased to announce that Kyriaki Giannouli has joined the Index remotely for a three-month, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works on Mount Athos (Greece) into the database!

Kyriaki is a doctoral candidate specializing in Byzantine History at the University of Ioannina and a professional conservator of paintings. Her research focuses on examining the significance of Greek landscapes within the travelogues of Western Holy Land pilgrims from the 12th to the 17th centuries. She is an expert in Byzantine portable icons, frescoes, coins and seals and has hands-on experience in creating specialized conservation reports and working with databases.

At the Index, Kyriaki has started working on enamel and metalwork backfiles and has already made digitally available several objects on Mount Athos, including a fourteenth-century chalice from Vatopedi monastery (Index system number mar20240205001) and an eleventh-century book cover from Lavra monastery (Index system number mar20240212001). Her position requires her to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. This will allow scholars worldwide, who are not able to travel to use the print Index on the Princeton campus, to access these images and their metadata. We are very excited and grateful to have Kyriaki join us in this collaboration!

This position is part of a multi-year project focusing on Mount Athos-related collections at Princeton (https://athoslegacy.project.princeton.edu/) and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.

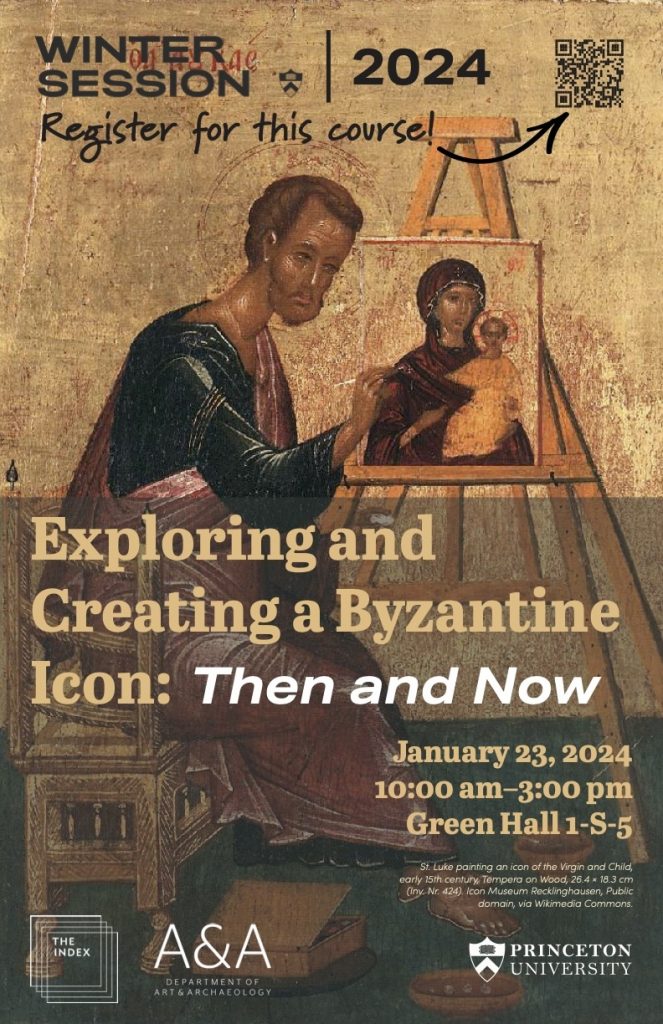

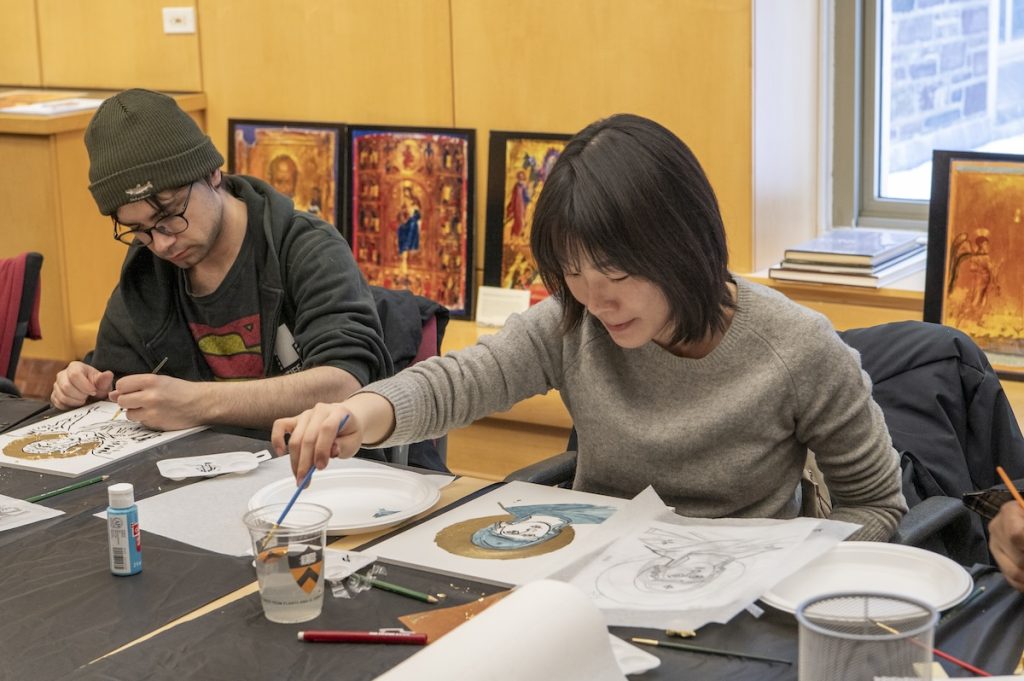

The Index of Medieval Art was delighted to offer its second Wintersession, “Exploring and Creating a Byzantine Icon: Then and Now,” on January 23rd, 2024. Its fifteen participants included Princeton staff, faculty, undergraduate and graduate students. In the first part of the workshop, they learned about the history and creation of Byzantine icons. In the second, they had the opportunity to create their own icons using modern artistic materials.

Index Art History Specialists Maria Alessia Rossi and Jessica Savage led the workshop, opening with a presentation on the Index resources and delving into some questions about iconography using large reproductions of the icons from Mount Sinai, generously loaned by Visual Resources, as a basis. The group discussed the iconographic details in works of art, exploring the subject matter in icons that generate tags in the Index database. Jessica invited the students to observe the figures and scene in a twelfth-century Sinai icon of the Annunciation (Index system no. 57527), looking for major and minor details in the painting, as small as an octopus swimming underwater. Alessia introduced participants to the way Byzantine icons were displayed and their devotional practices by examining a folio from the Hamilton Greek Psalter (Index system no. 103381).

The first guest lecturer, local icon painter Maureen McCormick, showed the participants how to make the binder for egg tempera paint by mixing egg yolk and … No, not water … rather, white wine! Maureen showed the class all the tricks of the icon painter, including where to buy authentic pigments, how to grind them, and how to literally use one’s breath to “blow” gold leaf onto a red clay bole sample, which formed the nimbus of a saint. A short Instagram reel was made by Kirstin Ohrt, Communications Specialist in the Department of Art & Archaeology, to show Maureen’s breathtaking lesson in action, and you can check it out here: https://www.instagram.com/artandarchaeologyprinceton/reel/C2ud3gZLAJW/.

The afternoon session was led by Department of Art & Archaeology graduate student and icon painter, Megan Coates, who spoke about her own work with icons, as well as their importance for memory and communication. As part of an organized hands-on activity, participants created their own Byzantine icons using templates designed by Megan or choosing their own models from books or memory. Acrylic paint, brushes, drawing materials, gessoed panels, as well as gold and silver leaf materials were supplied by the Princeton Office of Campus Engagement. The outcomes were astonishing!

It was a pleasure to observe the participant’s ideas and skillful process unfold as they engaged in the long-treasured art of icon-making. One participant Sigrid Adriaenssens, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, wrote to us after Wintersession and said, “Thank you so much for organizing this workshop. It opened a whole new world to me that I didn’t know existed at Princeton. I really enjoyed learning about the Index, icons, and how they are made. The speakers Maureen and Megan were also very interesting and exciting to listen to!” Another participant, Zi (Zoe) Wang, visiting doctoral candidate and researcher at Princeton from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, said she felt transported by the instrumental music we played during the hands-on activity. Zoe said about the experience, it was like “immersing myself in meditation.” We couldn’t agree more!

Are you interested in learning more and researching icons at the Index? Here are some general tips for starting an Index search about Byzantine icons, especially if you do not know exactly which icon you are looking for!

However, these results might be too broad, so if you want to refine them you can keyword search the word “Byzantine” on the upper right search window of the database, and then filter by these other controlled terms we just mentioned, such as Work of Art Type “panel” or Medium “wood.” But if you want even narrower results, or if you know the iconography you are interested in, such as the iconography of an angel, or searching for angels by name, as in the case with the Annunciation image, you can filter by the Subject “Gabriel the Archangel.”

If you have any questions about starting research with the Index resources, fill out our inquiry form and we will be in touch: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/.

Finally, this Wintersession workshop could not have been possible without the generous support of the Princeton Office of Campus Engagement, the Department of Art & Archaeology, and the Index of Medieval Art. Thank you to all who helped plan and participated in this event!

As editorial staff at the Index continue cataloging our physical backfiles, which contain over 200,000 photographs of works of art in sixteen media categories, we are happy to announce that at last, all our print records of gold glass objects have been fully digitized in the Index database! In gold glass, an image in gold leaf is fused between layers of glass. Gold glass was a favored art form in Hellenistic Greece and during the Roman period, often decorating the bases of feasting vessels, such as bowls, cups, and plates, with hidden pictures that would slowly be revealed during the consumption of food and wine. The newly digitized “Gold Glass” backfiles document over 650 objects from about 60 locations. Most examples are identified as vessels, medallions, or plaques (Fig. 1).

The glittering portraits on these glass objects, now mostly fragmentary, are usually bust length and often show whole families. These are classified under the Index subject “Family Group,” while the subject “Married Pair” is used for images depicting a bride and groom, sometimes crowned by Christ. Gold glass objects are frequently associated with marriage celebrations, and several pieces retain the names of the men and women depicted with inscriptions of good wishes. Frequently, this inscription is the Latin drinking toast “PIE ZESES” (“Drink to live,”), either in full or abbreviated, although a fourth-century gold glass fragment from Rome, now in the British Museum, bears the more sentimental words “DVLCIS ANIMA VIVAS” (“Sweet soul, may you live [long]”) around the heads of the newlyweds (Fig. 2).

Several gold glass objects contain other paired figures, especially Peter and Paul the Apostles, as the patron saints of Rome, and Adam and Eve, commonly represented in the Fall of Man scene. Old Testament narratives and figures, such as Moses, Abraham, Daniel, and Jonah were popular, and Christian miracles were also frequently depicted on vessels. The Index database contains just over fifty miracle scenes executed in the gold glass medium, including the Raising of Lazarus, the Miracle of Loaves, and the Wedding at Cana, suggesting that healing themes held some favor among patrons. The objects may also have served a commemorative function.

Some surviving gold glass objects contain Jewish iconographic motifs, including the Temple implements, such as the menorah, shofar, etrog, and Torah Ark. These implements can be found in the Index database by browsing the Subject list, or by searching for “gold glass” as a term and filtering by the Style/Culture “Jewish.” Mythological figures and narratives from the classical world were also favored subjects to depict on gold glass vessels. The Herculean labors, sea-nymphs, and cupids can be identified on some fragments. Other well-represented motifs in the medium include the “Good Shepherd,” which has iconographic connections to the ancient Greek ram-bearing cult figure Kriophoros. There remains much to discover and assess about images in gold glass and their meanings, production, and patronage throughout the late antique, Roman, and Byzantine periods, making the Index an essential study tool. Now, with increased access, more researchers can learn how this rather fragile art form documents fashion, commerce, rituals, and historical names and epigraphs from ancient daily life (Fig. 3).

The Index gold glass backfiles received significant attention by Ryan Gerber, our 2019 summer intern from the Rutgers School of Communication, who is now a Marquand Art Library Collections Specialist. Gerber inventoried the collection and wrote about his impressions in a blog post called “A Face in Gold Glass.” After Henry D. Schilb, Index Art History Specialist in Byzantine Art, finished adding the collection with the help of Gerber’s inventory, he noted that many gold glass objects recorded in major nineteenth century catalogs did not survive into the modern era. Thus, the publications that earlier Index catalogers used in their research may have contained the last known record of an object’s existence. Schilb said, “it was surprising to learn that many of the gold glass objects entered into the Index files have been lost to time, and at least one of them was apparently reduced to dust in the collection where it was last recorded. Not surprisingly, we have also simply lost track of several examples that were originally cataloged by Indexers before the Second World War.” With too little information to go on, the Index cataloger can sometimes upload only a drawing from the catalog and record only a “Last Known Location” for objects presumed lost to history. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this in the database by giving “Unknown” as the current location with a “Last Known Location” to identify the place where an item was last known to exist. This can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are either simply lost or are now in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s true current location, that bit of data can sometimes elude us, so we always welcome intelligence from anyone who might have a good lead!

It is a great achievement when we can complete an entire category in the backfiles with newly researched information, including updated location names, fuller iconographic descriptions, and new or updated terms from Index vocabularies to expand the findability of work of art records. We ought to be clear, however, that we do not claim to have recorded every known example of any medium or type of object. That must remain an ongoing project. Nevertheless, the whole Index team is thrilled to make the gold glass corpus of the original Index card catalog fully available in the database. If you want to see for yourself, you can browse “gold glass” records by Medium more fully here: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/list/ListMediums.action. You can also reach out to us with any inquiry here: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/. Please let us know how the Index can improve the records we have, or find out how the Index can serve your own research needs.

Cheers!

Further Resources

Garrucci, Raffaele. Vetri ornati di figure in oro: Trovati nei cimiteri dei cristiani primitivi di roma. Rome: Tipografia Salviucci, 1858.

Deville, Achille. Histoire de l’art de la verrerie dans l’antiquité. Paris: Morel, 1871.

Vopel, Hermann. Die Altchristlichen Goldgläser: Ein Beitrag zur altchristlichen Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte. Freiburg im Breisgau: J. C. B. Mohr, 1899.

Morey, Charles Rufus. The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library: With Additional Catalogues of Other Gold-Glass Collections, ed. Guy Ferrari. Vatican City: Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1959.

Meek, Andrew. New Light on Old Glass: Recent Research on Byzantine Mosaics and Glass. London: British Museum Press, 2013.

Howells, Daniel Thomas. A Catalogue of the Late Antique Gold Glass in the British Museum. London, British Museum Press, 2015.