Are you familiar with the popular iconography of the saint whose feast day falls on April 23? If you’ve ever been to an English pub, you probably are, even if you didn’t realize it! According to medieval legend, Saint George of Cappadocia was the third-century saint and martyr who slew a dragon. Usually, George is represented as a knight mounted on a horse. Sometimes shown carrying a cross-inscribed shield, his red and white armorial attribute, he thrusts his lance into the jaws of the dragon under his horse’s hooves.

George’s heroic posture was modeled on the iconography of other saints and mythological figures. Theodore Tyro and Demetrius of Thessalonica, for example, also slew beasts in the name of vanquishing evil. Carrying talismanic or protective power for people threatened by worldly dangers, dragon-slayer images decorated many small, portable objects, including ampullae, lamps, carved gems and small plaques from the late antique, Byzantine, and Coptic worlds.1 Building on narratives of his heroism, tales of George’s life and deeds spread throughout medieval Europe with Crusaders returning from the East. By the high Middle Ages, the Golden Legend, a compilation of saints’ lives by Jacobus de Voragine, fleshed out the life of George with a rescue narrative of a king’s daughter and inspired numerous visual representations in different media.2

Depictions of the rescue legend, which follow standard iconography for George’s slaying of the dragon, often insert the princess as a minor character of relative insignificance. But is she insignificant? Traditionally identified as a third or fourth century Komnenian princess of Trebizond, she is sometimes named Sabra or Cleodolinda (or Cleolinda, Cleudolinda) (Fig. 1). According to the legend, the princess was weeping profusely, anticipating her certain death as the next human sacrifice to the dragon, when George arrived at a town called Silene in Libya. He pledged to help her, and he rode toward the dragon with his sword drawn.3 In swift succession, George pierced the dragon and the princess bound her girdle around the beast’s neck. She led it back to the townspeople alive which brought about the people’s mass conversion to Christianity.

In some earlier depictions of the legend, the princess appears with prominence, including on a Romanesque capital from a monastery in Saint-Pons-de-Thomières now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the capital face, the princess wears a long dress, props one hand on her hip, and extends a flower toward George (Fig. 2). Around the other side, George kneels behind his shield, trailing a coiled serpent that approaches the princess from behind. Her thank offering to George in the midst of his attack on the dragon suggests that there will be a good outcome despite the violence surrounding her.

In another Romanesque capital from the abbey of Saint-Pierre of Airvault in Poitou, the princess stands behind George, although he rides away from her, effectively separating her from the dragon’s reach (Fig. 3). With George exiting left, the princess becomes a key figure of interest to viewers gazing upward at the capital. Here, she maintains a stoic stance, and, in ironic juxtaposition with the nearby head of a menacing grotesque, her arms are crossed over her body in a way that suggests patience and perseverance in the face of danger.

By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the iconography of the princess and her role in George’s slaying of the dragon were handled with more flexibility, especially in manuscript illumination.5 Some examples, such as the Hungarian Angevin Legendary, illustrate the narrative more literally, showing the princess tethering the dragon or leading it away by its makeshift leash (Fig. 4). In this variant of her iconography, the Princess of Trebizond is actively engaged with George’s feat and secures the dragon in one forceful pull.

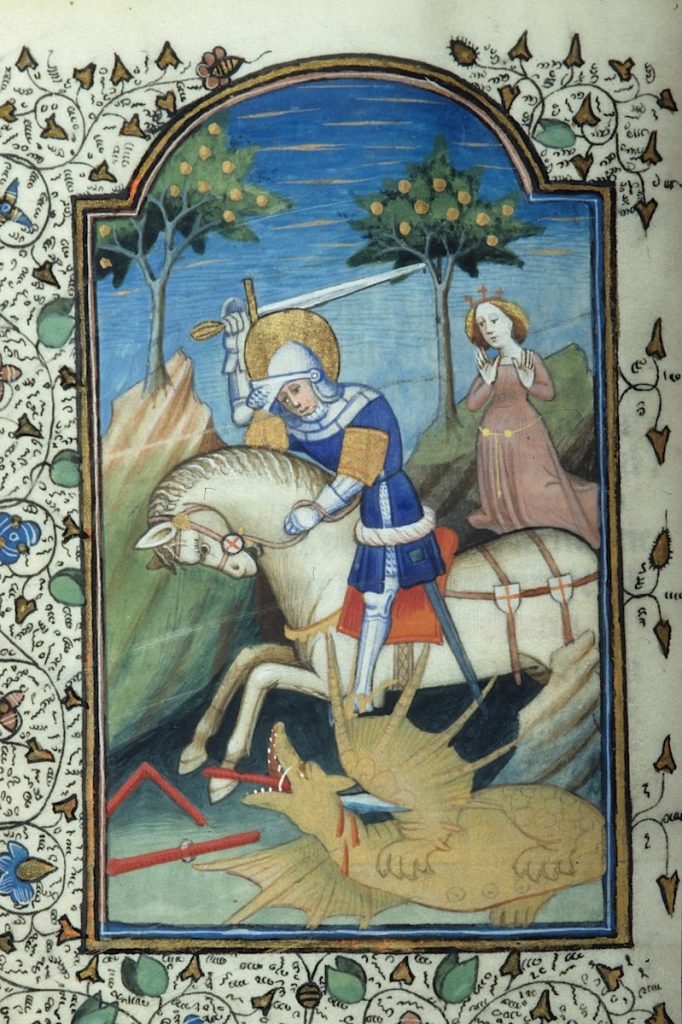

At George’s suffrage in illuminated prayerbooks, especially in Books of Hours, the princess often appears behind the slaying scene, kneeling in prayer, and protected a distance.6 But in some of these late medieval depictions, she tends a flock of sheep, sometimes holding one sheep on a lead, or she simply raises her hands in surprise at George’s victory (Fig. 5).7

In all these images, the princess functions as more than a mere attribute of George. Instead, she is actively reimagined as part of the narrative. Artists creatively customized their images of Georgian legend to not only explore the princess’s instrumental role in her rescue but to highlight her intercessory function in saving the townspeople–in a literal sense and by their newfound faith. Whether showing her as prayerful, gracious, surprised, or tethering the dragon, the iconography of the princess offers a versatile model of female agency, one that likely inspired her viewers.

We can find echoes of such rescue narratives in other ages and media. If you have played the classic Super Mario Bros. video game, then you know the game’s mission: rescue Princess Peach! As aficionados know, the eighth and final world of the game culminated in an underground battle with Bowser, the hammer-hurling, spiky-shelled antagonist (Fig. 6). If you hurled enough fireballs back at Bowser, he overturned and descended into an abyss off screen, allowing Mario to advance over the bridge and reach the princess on the other side. Much like the Princess of Trebizond, Princess Peach had to be rescued, and she, too, has been reimagined over time: her characterization within the Nintendo empire of games and films eventually evolved from damsel in a dungeon to a fighter in her own right.8

You can still find the iconography of George slaying the dragon in the modern world, often in a reduced composition of equestrian, saint, and dragon. Once you know what you’re looking for, you’ll spot George in any number of settings, especially on pub signs like the one on my local haunt when I was a grad student in London (Fig. 7). Whether under his sign or not, those who cheer to Saint George today would do well to remember this: once upon a time, a princess filled with purposeful character also conquered a beast.

Thank You, Saint George! Your Quest is Over.

Appendix

The Index subject files provide a starting point to locate examples of the Princess of Trebizond in the six works of art:

The Index is pleased to announce the launch of a new digital resource for the study of Byzantine iconography, the Lois Drewer Calendar of Saints in Byzantine Manuscripts and Frescoes. Compiled by the late Lois Drewer, PhD, longtime specialist in Byzantine art at the Index, this calendar identifies saints, cites standard and hagiographic references (with a guide to their abbreviations), and concisely describes manuscript illuminations and frescoes. The calendar is organized by feast days in the Constantinopolitan calendar.

There are four main ways to browse the resource. The first is by selecting a month and day under the tab for calendar. This entry point leads to the core of the data, and we recommend this as a good place to start. For example, searching today’s date of the fifth of March reveals three entries for saints: 1. Mark of Egypt; 2. Conon the Gardner; and 3. Hypatius of Gangra. The list you will find there offers identifications, references, and examples.

Many of the saints and holy martyrs included in Dr. Drewer’s calendar are obscure or infrequently represented in medieval art, such as Conon the Gardener (also known as Conon of Perga), a gardener from Nazareth martyred under the Roman emperor Decius (r. 249–251 CE).[1] In some cases, the iconography has not yet been cataloged by the Index, making this an especially useful additional resource.

There are also two lists for iconographic motifs and iconographic scenes with feast days linked on the right, and a list of feasts days organized A to Z. The iconographic motifs and scenes are grouped alphabetically beneath bold headings.

A majority of the headings in this resource cover martyrdom and torture scenes for Byzantine saints–among them holy martyrs, hermits, prophets, and women, but Drewer also included groups for various vestments and clothing, human gestures, attributes, and objects. For example, it is possible to see that an axe is associated with John the Baptist.

In some examples of medieval iconography, the preaching John the Baptist is depicted pointing to an axe at the base of a tree, a reference to Matthew 3:10. Or you can discover that the representation of grief is linked to Sophia of Rome, who is portrayed in various scenes as mournfully throwing out her arms in response to the beheadings of her daughters Pistis, Elpis, and Agape.

There is much to discover by browsing these lists, and we expect that this resource may usefully supplement your searches within the wider Index of Medieval Art Database. You may also try browsing the Svetlana Tomeković Database of Byzantine Art for similar themes represented in Byzantine art. We welcome your feedback, and we look forward to receiving questions through our research inquiries form.

We warmly thank the Index’s Technology Manager Jon Niola for bringing this project to fruition. Lois Drewer dedicated much of her life to iconographic research, and we feel certain that she would have approved of this posthumous tribute. We are proud to offer this additional resource so that all may benefit from Dr. Drewer’s calendar of saints.

[1] Drewer’s database notes three instances of the iconography of the holy martyr Conon the Gardener: a small illustrated Menologion, 1322-1340 (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. f. 1, fol. 30v), and two frescoes in the south aisle of the narthex in Dečani and in the dome of the south tower narthex in Treskavec, all of which have yet to be added to the Index database.

As a victorious angel, defender, and leader of heavenly armies, Michael the Archangel is often depicted in medieval art as an armored soldier carrying such arms as a cross-inscribed shield, cross-staff, or the sword or spear he typically employs to fight the dragon in the “great battle of heaven” (Apocalypse 12:7–9; see the Index subject Apocalypse, Dragon Attacked by Michael). Outside of the apocalyptic combat scene, Michael also may be shown trampling and piercing the dragon as part of his overall iconography. This figuration of Michael as the triumphant archangel lent a devotional and meditative aspect to his veneration as an overcomer of evil, as is often clear in images related to the Christian feast of Michaelmas. The feast’s name in English derived from “Michael’s Mass” and is traditionally observed in some Western churches on the 29th of September. While Michaelmas was primarily celebrated to acknowledge the works of Michael the Archangel, this feast also celebrated the help and intercession of all angels. Michaelmas also bore secular significance for medieval people as a “quarter day” of the financial year, which signaled the fulfillment of various business obligations, and the close of the agricultural year (For more on this holiday, see Ben Johnson, Michaelmas, The Blog of Historic UK).

At this time of Michaelmas, a dive into the online collection of the Index of Medieval Art reveals a wealth of examples tied to the iconography of the revered archangel. The most common representation is of Michael the Archangel fighting the dragon. In the language of the Index, that’s Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Dragon. This subject heading is attached to nearly 300 works of art in the database applied to a variety of media, including a Romanesque limestone relief panel from Burgundy, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris (Fig. 1). A closely related subject, Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Satan, is applied to works of art in which the dragon has morphed into a devilish creature, usually shown with horns and clawed feet. Like the hapless dragon, this creature is similarly impaled and trampled! Exploring these two similar subjects reveals a later preference for the literal depiction of devils in place of dragons. Michael the Archangel also features in other important episodes, such as the biblical narrative of the Fall of Angels and the Last Judgment of Christ (Figs. 2 & 3). In Last Judgment scenes, Michael the Archangel is often shown holding the scales of justice laden with good and bad souls (See the Index subject Weighing of Soul).

A fifteenth-century alabaster panel from England combines many aspects of Michael’s typical iconography: here, wearing a suit of armor that resembles feathers, he also bears a shield and raises his sword over the vanquished dragon. One weighing pan of his scales remains, holding a devil head, while behind him, a crowned Virgin intercedes to emphasize mercy with justice (Fig. 4).

In the Index database, Michael the Archangel is by far the best represented of the archangels, with thirteen subjects covering his various roles, from intercessor and commanding soldier to apparition in visions and legends. A common legendary context for Michael is that of the “Runaway Bull” in the Golden Legend. According to the legend, a wayward bull belonging to Garganus, a wealthy man from Siponto, is miraculously saved from the shot of an arrow, which instead reversed in midair and killed the huntsman. As an explanation for this strange occurrence, Michael the Archangel appears to a local bishop to reinforce the idea of grace at the bull’s saving and to tell him to build a church in his honor (Fig. 5). The hilltop sanctuary of San Michele del Gargano is still a popular site of pilgrimage in the town of Monte Sant’Angelo in southern Italy.

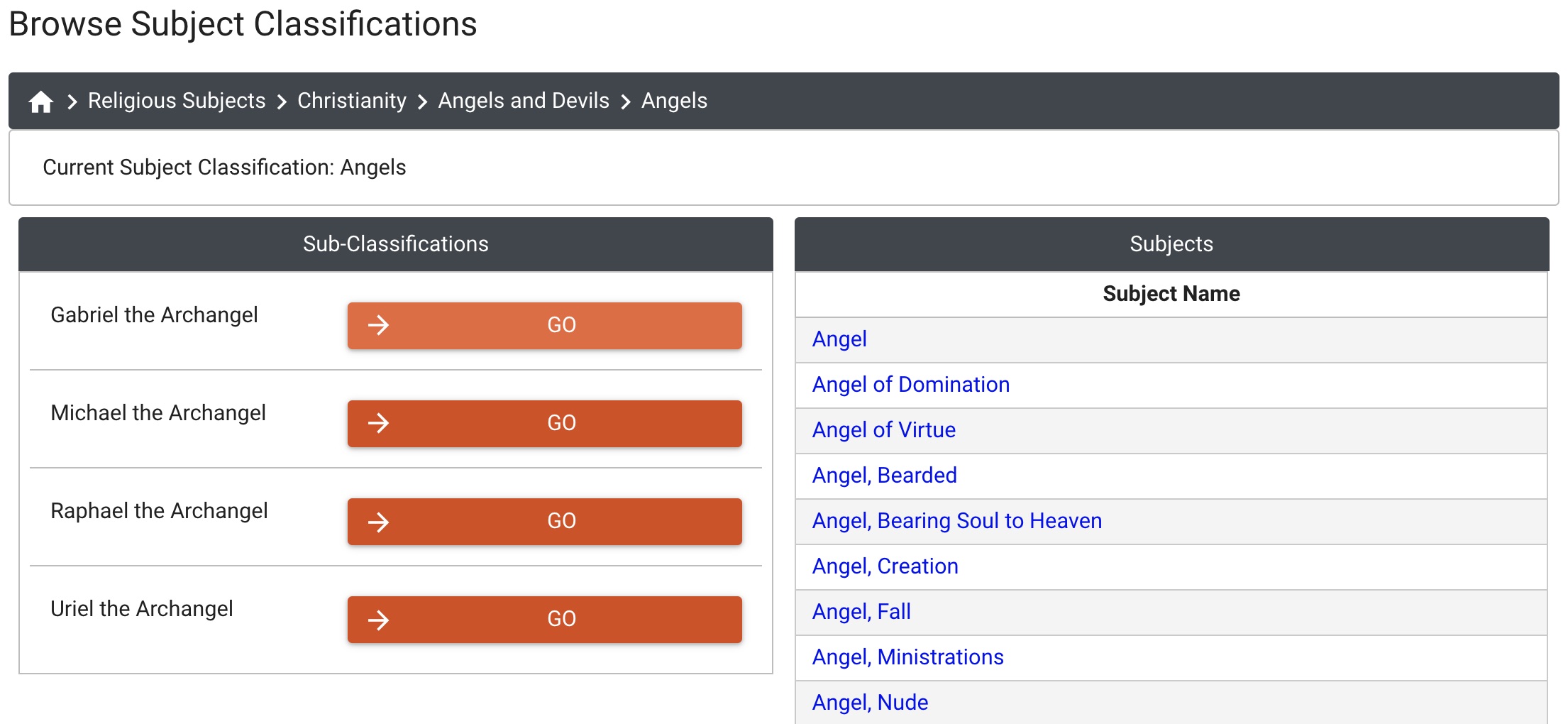

For a more general overview of the iconography of angels in the Index database, we encourage you to browse sections of the new subject classification network by clicking “Browse” and proceeding to the link for “Subject Classification.” From here, click on Religious Subjects, then Christianity, then Angels and Devils. In the sub-group of Angels, you will encounter a list of over twenty iconographic headings associated with various angels, including seraphs, cherubs, and several more subjects for angels engaged in specific actions, such as “Protecting Soul” and “Pursuing Devil.” On the left are further divisions for the four major archangels of Christian angelology—Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, and Michael—which list the individual subjects related to each. At the bottom of each authority for these subjects, you’ll see a bar for “Work of Art References” that will take you to the relevant work of art records.

Detail of Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent. Old Testament Picture Book. French, c. 1250. Morgan Library, M.638, fol. 8r

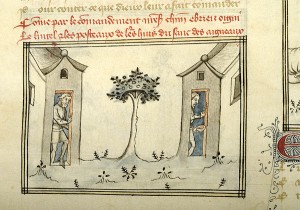

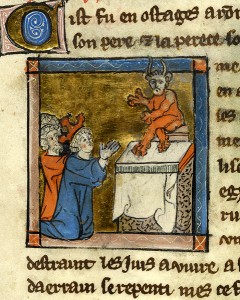

Nine times Moses went to the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II to demand freedom for the Israelites in captivity, saying “Let my people go.” Each time Moses and his brother Aaron were sent a way, an episode classified by the Index as, Moses and Aaron: driven from Pharaoh’s Presence. Despite these increasingly tense exchanges, and then a marvelous act that changed Aaron’s rod into a serpent before the Pharaoh’s court (Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent), Ramses still refused to release the Israelites from slavery.

What followed was the foretold wrath of God enacted as ten crippling plagues on the Egyptians. In the first wave of calamities, there were plagues of blood, frogs, gnats, and lice that polluted the air and water. The second wave, brought plagues of flies, diseased livestock, and boils. Then came hail, locusts, and darkness that fell on Egypt for three days. The tenth and final plague, the “Plague of the Firstborn,” claimed the lives of the eldest children in all Egyptian families. The Index of Christian Art classifies the subjects of the Exodus plagues under the major figure of Moses:

Moses: Plagues of Flies, Frogs, Locusts, Hail and Pestilence. Stuttgart Psalter, c. 820-830. Stuttgart Landesbibliothek, Bibl.fol.23, fol. 93r. Photograph by Gabriel Millet.

(Exodus 9:6-7)

The final plague is described in several phases throughout the books of Exodus (11:4-8; 12:1-13, 21-23, 29-30). Moses first warns of its coming to the embattled Ramses, but his warning is dismissed.

Facing the impending deadly plague, Moses instructs the Israelites to make a sacrificial offering to God, and to use the blood of the animal – a male yearling – to mark the doorposts and lintels of their homes. Moses explains to them that marking their homes this way will spare their firstborn children from the “death angel,” saying he “will pass over the door.” (Exodus 12:23).

Moses: Plague of Firstborn. Two Israelites marking the doorposts and lintels of their homes with the blood of the sacrificial lamb. History Bible, Paris, c. 1390. Morgan Library, M.526, fol. 14v

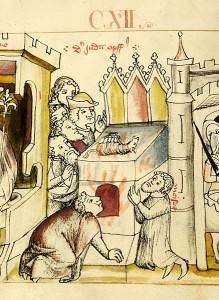

Detail of Moses: Passover. Israelites cooking the sacrificial lamb under the inscription “Die Juden Opffer.” Historien Bibel, Swabia, late 14c. Morgan Library, M.268, fol. 7v

Following this, the Israelites were delivered from bondage and departed from Egypt. The Exodus is remembered at the feast of Passover – the Hebrew feast of Pesach – with special instructions for preparing, eating, and storing traditional, often symbolic food. While Passover traditions have varied over time and from one region to another, it is generally a family holiday in which the meal is accompanied by readings, songs, and traditional rituals designed to remind the celebrants of the Exodus story and the hopes for a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. The order of the seder, or Passover meal, is set out in a book known as the Haggadah, which was sometimes richly illuminated in the Middle Ages, as shown here in the Sarajevo Haggadah, originating in Barcelona in the middle of the 14th century. Well-known related manuscripts to this Haggadah include the Rylands Haggadah and the Simeon Haggadah. The Index classifies subjects depicting the original Passover feast as Moses: Passover, Moses: Passover proclaimed, and Moses: Law, Feast of Passover and with a general heading for Scene: Passover.

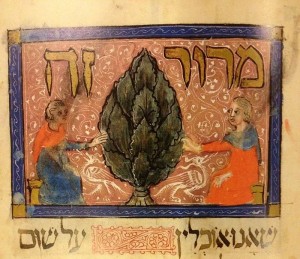

Bitter herb or “maror” in the Sarajevo Haggadah. Barcelona, c. 1350. Sarajevo, National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photograph Wikimedia Commons.

“And when he was come into Jerusalem, the whole city was moved, saying: Who is this? And the people said: This is Jesus the prophet, from Nazareth of Galilee.” (Matthew 21:10-11)

Celebrated seven days before Easter Sunday, Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Passion Week and commemorates Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The episode, which appears in the four canonical gospels, describes the multitudes gathering at the gates of Jerusalem to welcome Jesus, laying their cloaks and branches on the ground in recognition of his status as the Messiah.

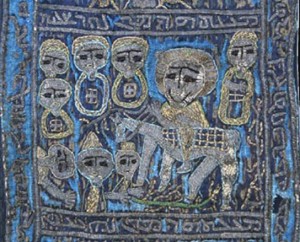

The earliest extant pictorial representations of the Entry into Jerusalem date to the fourth century, and the subject was popular across media throughout the Middle Ages. A highly compressed version of the episode appears on a fourteenth-century ivory diptych from the Abbey of Muri, Switzerland, which is decorated with Passion scenes. The right side of one of the leaves portrays a single disciple trailing the mounted Christ blessing two figures, who serve as shorthand for the multitudes. Equally schematic is the Entry into Jerusalem on the batrashil of bishop Athanasius Abraham Yaghmur of Nebek, produced in Syria in the fourteenth century. This long, embroidered stole shows three figures placing a palm branch before Christ, riding on an ass and attended by five disciples.

The lintel from the main portal of the twelfth-century church of San Leonardo al Frigido in Italy presents a more expansive version of the scene by illustrating all twelve disciples, their open mouths perhaps indicative of speech, and three small figures perched in a tree on the right-hand side of the composition. The last detail, common in depictions of the subject, relates to the prophecy of Zechariah, which describes children breaking branches from an olive tree and following the crowd into Jerusalem.

Celebrated annually on February 14 as a day for courtship and romance, Valentine’s Day began as a liturgical celebration in honor of one or more Early Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The Roman Martyrology mentions two Valentines, both of whom were decapitated on the ancient Via Flaminia, the main artery connecting the city of Rome to the Adriatic Sea. One Valentine died in Rome and seems to have been a priest. The other, who may have been a bishop, was martyred approximately 60 miles away at Interamna (modern Terni).

The earliest extant connection between Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (1383): “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” February 14 was associated with courtly love as early as 1400, in a charter ostensibly issued by Charles VI of France (d. 1422). The text describes the festivities of the royal court, which included love poetry competitions, dancing, jousting, and a feast. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm evidence linking Valentine’s Day with the ancient Roman Lupercalia, a pastoral festival observed from February 13 through 15 to purify the city of Rome and to promote health and fertility.

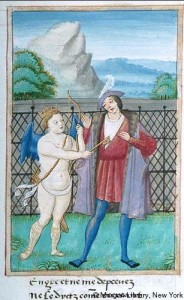

The Index of Christian Art is delighted to present four images thematically associated with Valentine’s Day. First, the nimbed Valentine of Rome is represented with the sword of his martyrdom in the fifteenth-century Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Morgan Library, M.917 and M.945). Second, a sixteenth-century Roman de la Rose contains a charming depiction of the God of Love locking the Lover’s heart with a giant key (Morgan Library, M.948). Third, a fourteenth-century ivory box cover of Parisian origin shows women defending the castle of love, a popular subject in late medieval courtly circles. The winged god of love at the top of the roundel prepares to launch his arrow, while women throw flowers at the attacking knights. Last, a sixteenth-century drawing from an Arma Christi and Prayers (Princeton University Library, Taylor 17), which portrays Christ’s heart with three blossoming flowers, is inscribed pyte, love, and charyte.

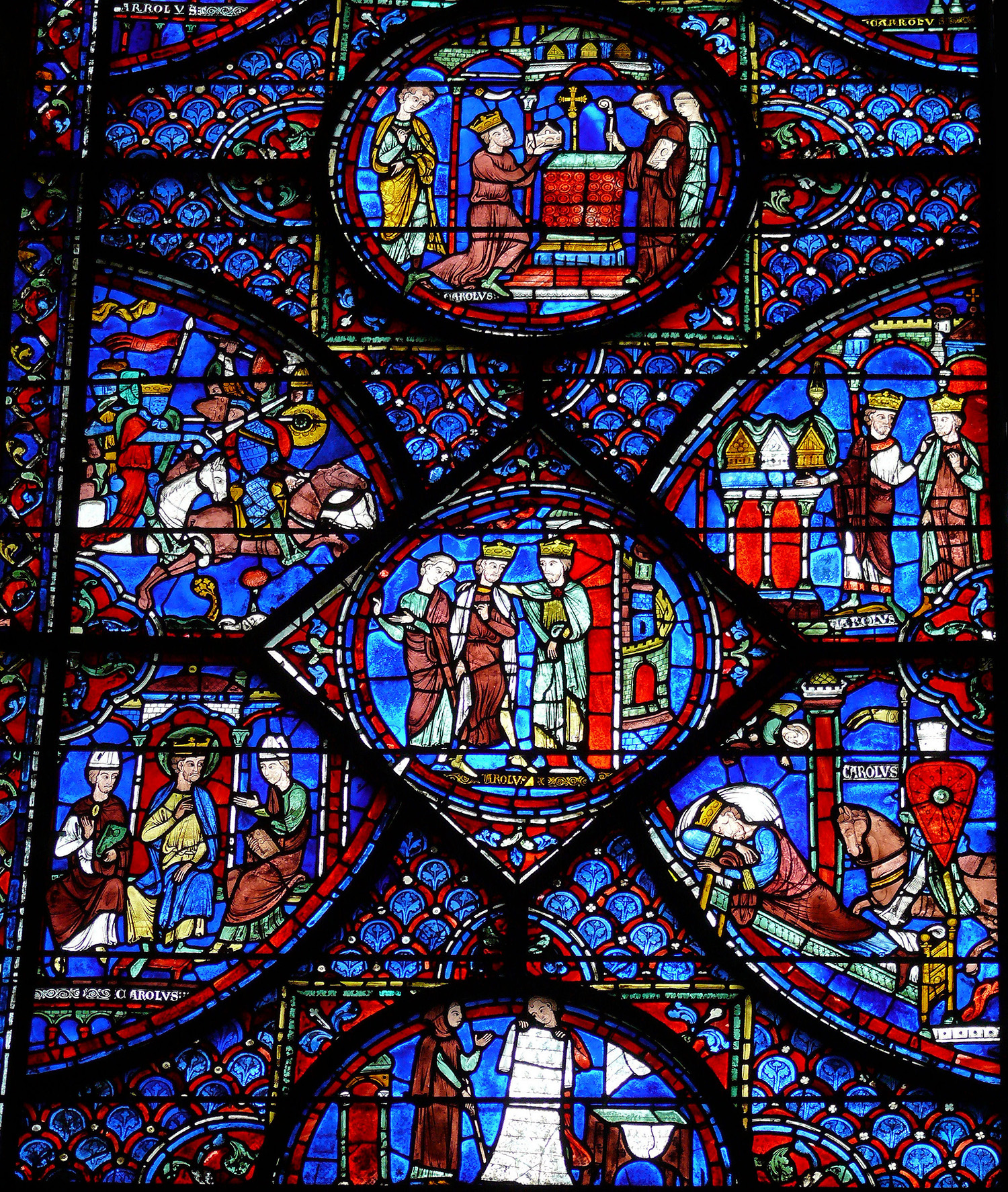

Today marks the feast day of Saint Charlemagne. The Frankish leader was canonized by the antipope Paschal III in 1165, some three-and-a-half centuries after his death on January 28, 814. Political motivations assuredly played a role in this act given the pontiff’s desire to curry favor with Charlemagne’s successor, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Yet it is well worth remembering that distinctly local commemorations of the emperor had already been established throughout the original footprint of the Carolingian empire.

Although Paschal III’s ordinances were officially revoked during the Third Lateran Council in 1179, Charlemagne remained a figure of veneration, particularly in the cathedral of Aachen, which houses an elaborate thirteenth-century shrine containing his relics. On Karlstag, the twelfth-century liturgical chant Urbs Aquensis, urbs regalis is performed within the cathedral in celebration of the emperor’s memory. With its vivid language, the sequence evokes Charlemagne’s accomplishments by describing him as a soldier of Christ, just ruler, converter of infidels, and an all-around rex mundi triumphator. Such descriptors complement posthumous medieval depictions of the emperor, which are amply represented in the Index’s catalogue. Portrayed variously as a ruler, warrior, patron, and saint in different media, these figures of Charlemagne underscore the diversity of guises and legends that developed after the historical emperor’s death.

Hanukkah, the Feast of Dedication, also called “Festival of Lights,” commenced yesterday (December 6th) at sundown and will continue for eight days. Hanukkah was celebrated as early as the second century BCE to commemorate the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Under Greek imperial rule, many key Jewish practices had been outlawed and the Temple in Jerusalem was filled with pagan implements. The Hellenization of Jerusalem brought with it the dedication of the Temple to Zeus, the destruction of Holy Scriptures, and many crippling assaults against Jewish custom. The Book of Maccabees recounts the story of Judas Maccabeus, son of the priest Mattathias, and his brothers, who formed a revolt against the Seleucid Empire of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, eventually winning against his heir and successor Antiochus V (See I Maccabees 6). A series of battles ensued from 167 to 160 BCE to reclaim Jewish heritage and freedom to worship in the Temple.

The pinnacle win is classified in the Index under the subject heading, “Maccabees: Battle against Antiochus V” and covers thirteen works of art in the database, mostly in manuscript. Several siege scenes of the Maccabees against Antiochus V armies feature the “Animal: Elephant and Castle” iconography based on the passage in I Maccabees chapter 6. In the passage, Eleazar Avaran runs toward the elephant in royal armor which he believes might harbor the king. In a twist of fate, Eleazar stabs the elephant and it tramples and kills him. Other key Index subjects relating to the history of Hanukkah include, “Antiochus IV: Siege of Jerusalem,” “Antiochus IV: Pollution of Temple,” “Judas Maccabaeus: Cleansing of Sanctuary,” and “Judas Maccabaeus: Altar rededicated.” After the Jews reclaimed the Temple in Jerusalem, it was purified and reconsecrated by the lighting of a multi-branched oil lamp which miraculously burned for eight days; an event which would be marked with the celebration that we now know as Hanukkah.

In medieval times, the growing custom of illuminating the menorah lamp, usually displayed outwardly, fulfilled the rabbi’s decree to confirm the “miracle of lights” to the world. The Index classifies menorah imagery under the subject heading “Candelabrum,” using the keyword “menorah” in a description field. There are 177 database examples in a variety of media including stained glass, sculpture, mosaic, terra cotta, and manuscript illumination.