Celebrated annually on February 14 as a day for courtship and romance, Valentine’s Day began as a liturgical celebration in honor of one or more Early Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The Roman Martyrology mentions two Valentines, both of whom were decapitated on the ancient Via Flaminia, the main artery connecting the city of Rome to the Adriatic Sea. One Valentine died in Rome and seems to have been a priest. The other, who may have been a bishop, was martyred approximately 60 miles away at Interamna (modern Terni).

The earliest extant connection between Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (1383): “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” February 14 was associated with courtly love as early as 1400, in a charter ostensibly issued by Charles VI of France (d. 1422). The text describes the festivities of the royal court, which included love poetry competitions, dancing, jousting, and a feast. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm evidence linking Valentine’s Day with the ancient Roman Lupercalia, a pastoral festival observed from February 13 through 15 to purify the city of Rome and to promote health and fertility.

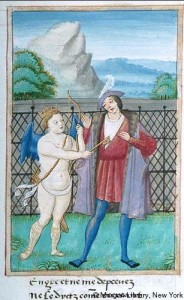

The Index of Christian Art is delighted to present four images thematically associated with Valentine’s Day. First, the nimbed Valentine of Rome is represented with the sword of his martyrdom in the fifteenth-century Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Morgan Library, M.917 and M.945). Second, a sixteenth-century Roman de la Rose contains a charming depiction of the God of Love locking the Lover’s heart with a giant key (Morgan Library, M.948). Third, a fourteenth-century ivory box cover of Parisian origin shows women defending the castle of love, a popular subject in late medieval courtly circles. The winged god of love at the top of the roundel prepares to launch his arrow, while women throw flowers at the attacking knights. Last, a sixteenth-century drawing from an Arma Christi and Prayers (Princeton University Library, Taylor 17), which portrays Christ’s heart with three blossoming flowers, is inscribed pyte, love, and charyte.

“Plus Ça Change…? The Lives and Afterlives of Medieval Iconography” takes place on April 29 at the Index of Christian Art. Presentations include:

“Rejection, Distortion and Destruction at Santa Maria in Trastevere.”

Dale Kinney, Professor of History of Art Emeritus, Bryn Mawr College

“The Archaeology of Carolingian Memory at Saint-Sernin of Toulouse.”

Catherine Fernandez, Research Scholar, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

“How Reliquaries Resist Iconographic Classification But Still Have Meaning”

Cynthia Hahn, Professor, Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center

“Signatures and Traces in the Art of al-Andalus.”

D. Fairchild Ruggles, Professor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

“Debating the Transfiguration In Fourteenth-Century Byzantium; or Why There Is No Hesychastic Art.”

Charles Barber, Professor, Princeton University

“The Frailty of Eyes.”

Kirk Ambrose, Professor and Chair, University of Colorado, Boulder

“Figuring Absence: Iconography and the Failure of Representation.”

Elina Gertsman, Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University

“The Work of Gothic Sculpture in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”

Jacqueline Jung, Associate Professor, Yale University

Generously co-sponsored by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, Princeton Medieval Studies, Princeton Art & Archaeology, and the Steward Fund in the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University. We look forward to seeing you!

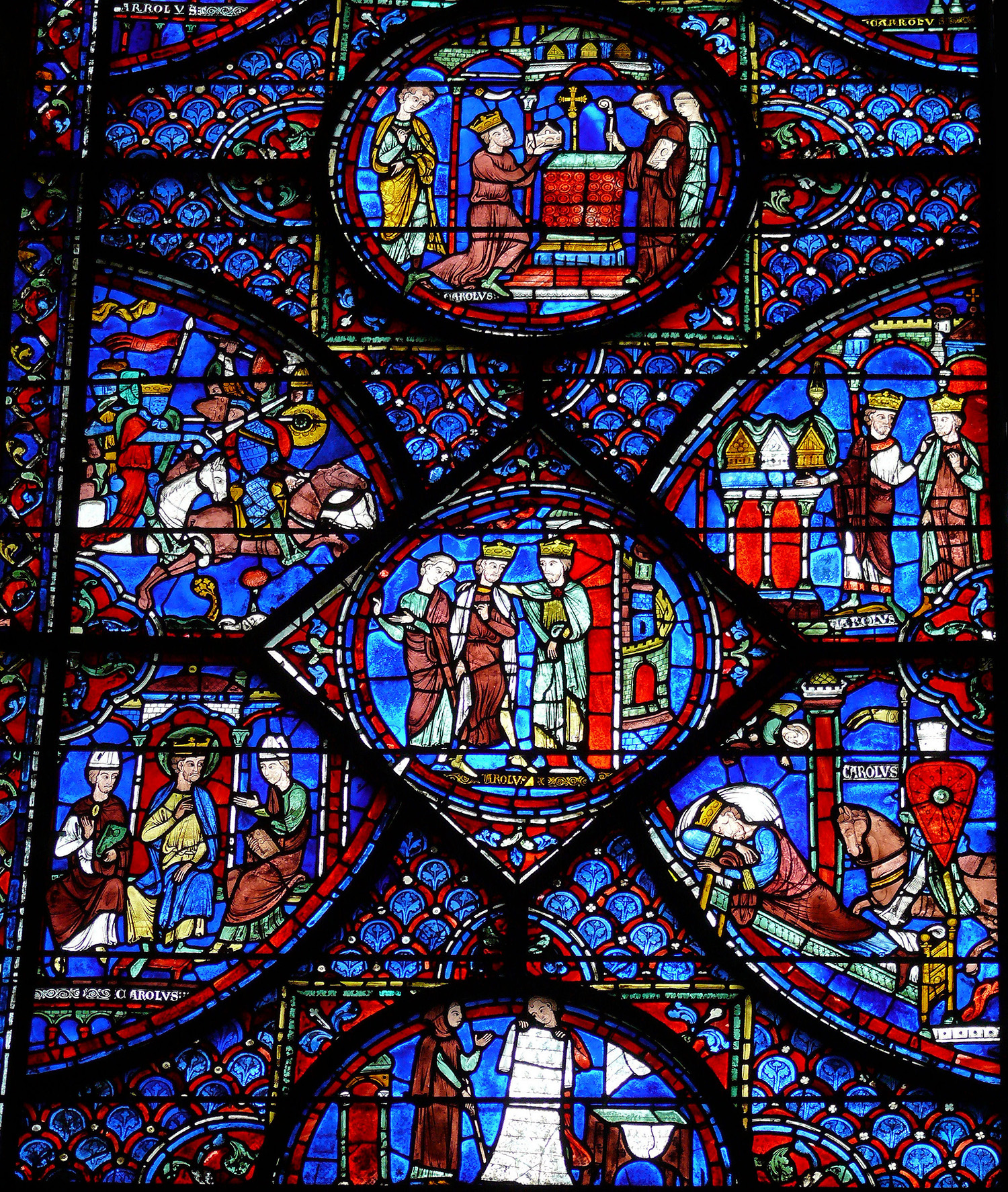

Today marks the feast day of Saint Charlemagne. The Frankish leader was canonized by the antipope Paschal III in 1165, some three-and-a-half centuries after his death on January 28, 814. Political motivations assuredly played a role in this act given the pontiff’s desire to curry favor with Charlemagne’s successor, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Yet it is well worth remembering that distinctly local commemorations of the emperor had already been established throughout the original footprint of the Carolingian empire.

Although Paschal III’s ordinances were officially revoked during the Third Lateran Council in 1179, Charlemagne remained a figure of veneration, particularly in the cathedral of Aachen, which houses an elaborate thirteenth-century shrine containing his relics. On Karlstag, the twelfth-century liturgical chant Urbs Aquensis, urbs regalis is performed within the cathedral in celebration of the emperor’s memory. With its vivid language, the sequence evokes Charlemagne’s accomplishments by describing him as a soldier of Christ, just ruler, converter of infidels, and an all-around rex mundi triumphator. Such descriptors complement posthumous medieval depictions of the emperor, which are amply represented in the Index’s catalogue. Portrayed variously as a ruler, warrior, patron, and saint in different media, these figures of Charlemagne underscore the diversity of guises and legends that developed after the historical emperor’s death.

Shepherd at the Nativity. Fourth century sarcophagus. Arles, Musée de l’Arles et de la Provence Antique, FAN.92.00.2517. Index system number 000107697.

Of all the medieval images associated with the Christmas story, surely most familiar is that of the Nativity, which depicts the Christ child in the lowly stable of his birth, almost always attended by the Virgin Mary, her husband Joseph, and the ubiquitous ox and ass. Medieval nativity scenes often included other onlookers as well, from the shepherds and magi to whom angels announced Jesus’ birth to the midwives who, in some accounts, assisted at it. Of all these figures, few have a longer or more engaging history than the shepherds, with whose homespun character and simple faith many ordinary medieval Christians could identify.

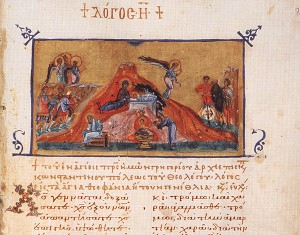

Shepherds and Magi at the Nativity. Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen, 11th century. Jerusalem: Greek Patriarchal Library, MS Taphou 14, fol. 80r. Index system number 150818

The shepherds themselves have biblical origins: Luke 2:8-20 describes them receiving news of Christ’s birth from a host of angels, then rushing to the stable to see the child for themselves. The scene of the angelic annunciation to the shepherds is sometimes presented adjacent to or in the background of the Nativity, and in the very late Middle Ages, under the influence of Franciscan piety, it was also depicted as an independent scene. However, from the beginnings of Christian art, the shepherds were also frequent onlookers at the Nativity itself. By the fourth century, Roman and Gallic sarcophagi had begun to include one or two shepherds standing beside the manger, often raising a hand in recognition of Jesus’ divinity; middle Byzantine mosaics often cast the shepherds as a trio to balance the three magi who also attended the child. Such pairings were encouraged by medieval texts that presented the shepherds as symbolizing the Jewish tradition from which Christianity had sprung and the magi as representing those pagans who converted to the faith. Alternatively, the magi and shepherds were sometimes presented as demonstrating Christ’s recognition by all walks of life, a universalistic message sometimes developed further in the portrayal of both groups as men of varying ages and even ethnicities.

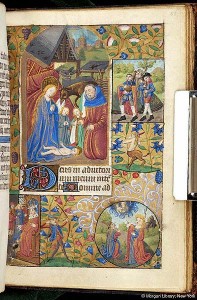

Music-making shepherds on the margin of the Nativity, ca. 1470. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS m.32 fol. 51r, Index system number 000175635

Late medieval pietistic trends, which promoted the idea that the poorest of men had been the first to receive news of Christ’s birth as confirmation of the value of humility and simplicity, encouraged fourteenth- and fifteenth-century artists to elaborate their images of the shepherds. They often are shown as rough-hewn peasant types—sometimes even including a shepherdess—who offer the child simple, heartfelt gifts, such as a lamb, a flute, flowers or, more unusually, a basket of eggs. The appeal of these humane, familiar figures still resonates in many a Christmas sermon as well as Christmas carols, from the traditional Austrian “Shepherd’s Carol” to the 1941 pop hit “The Little Drummer Boy.”

Shepherds are noted in over 650 records of the Nativity in the online database of the Index of Christian Art; many more can be found in the card files. Media include sculpture, gold glass, manuscripts, enamel, mosaic, fresco, and painting. We wish all our friends who celebrate Christmas a joyous and peaceful holiday.

Photo: The Aberdeen Bestiary Website (https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/comment/81risidf.hti; consulted 12/4/15)

Welcome to the new website of the Index of Christian Art. Our updated and more user-friendly design preserves many of the things researchers have counted on finding here: information about our history, holdings, and hours; additional image resources; news about events and publications, including the annual journal Studies in Iconography; and a link to our online database. However, it now also includes updated information about our staff and their projects, new information about our resources and services, and periodic blog posts on topics of interest to a range of medievalist researchers.

Our website redesign, created by our Technology Manager Jon Niola with content input from several of our research staff, represents only one of several initiatives under way at the Index this year. The most important to external researchers will be a total revamp of our venerable online database to allow for a friendlier design, more flexible, intuitive searches, and easier access to information and images. We hope to put this into place in time for the Index’s centennial in 2017. Other initiatives include the inauguration of Index Workshops, in which faculty and students in the department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton can join with Index and area scholars to workshop papers and publications in progress, and the revival of the well-known Index Conference Series, which reboots on April 29 with a one-day conference titled “Plus Ça Change? The Lives and Afterlives of Medieval Iconography.”

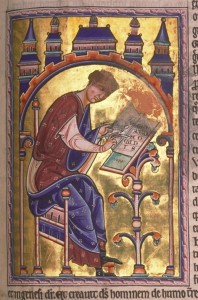

We would like to think that our technological updates would please St. Isidore of Seville (ca. 560-636), who in 1997 was nominated by Pope John Paul II to become patron saint of the Internet. Bishop of Seville for over thirty years, the learned Isidore richly deserves the honor: his most famous work, the 20-volume Etymologiae, attempted to summarize all human knowledge in the manner of Classical scholars. Its scope ranges from theology and the liberal arts to medicine, animals, and daily life, offering the reader a plethora of surprising and sometimes colorful details about such topics as the causes of an eclipse, the behavior of ants, and the names of various women’s garments. Its wide use and continued importance throughout the Middle Ages can be judged by its countless citations (dare we call them re-tweets?) in works by medieval authors, including such luminaries as Dante, Chaucer, Bocaccio, and Petrarch. Isidore of Seville is represented by 28 records in the Index, both in the database and physical card file; he is often shown writing busily at a lectern, as in the late twelfth-century Aberdeen Bestiary (Aberdeen University Library, MS. 24, fol. 81r). Further subject references to Isidore can be found under, “Clergy, Bishop: Isidore of Seville” and “Scribe, Male: Isidore of Seville.”