Celebrated annually on February 14 as a day for courtship and romance, Valentine’s Day began as a liturgical celebration in honor of one or more Early Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The Roman Martyrology mentions two Valentines, both of whom were decapitated on the ancient Via Flaminia, the main artery connecting the city of Rome to the Adriatic Sea. One Valentine died in Rome and seems to have been a priest. The other, who may have been a bishop, was martyred approximately 60 miles away at Interamna (modern Terni).

The earliest extant connection between Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (1383): “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” February 14 was associated with courtly love as early as 1400, in a charter ostensibly issued by Charles VI of France (d. 1422). The text describes the festivities of the royal court, which included love poetry competitions, dancing, jousting, and a feast. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm evidence linking Valentine’s Day with the ancient Roman Lupercalia, a pastoral festival observed from February 13 through 15 to purify the city of Rome and to promote health and fertility.

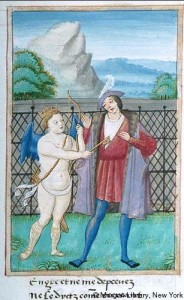

The Index of Christian Art is delighted to present four images thematically associated with Valentine’s Day. First, the nimbed Valentine of Rome is represented with the sword of his martyrdom in the fifteenth-century Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Morgan Library, M.917 and M.945). Second, a sixteenth-century Roman de la Rose contains a charming depiction of the God of Love locking the Lover’s heart with a giant key (Morgan Library, M.948). Third, a fourteenth-century ivory box cover of Parisian origin shows women defending the castle of love, a popular subject in late medieval courtly circles. The winged god of love at the top of the roundel prepares to launch his arrow, while women throw flowers at the attacking knights. Last, a sixteenth-century drawing from an Arma Christi and Prayers (Princeton University Library, Taylor 17), which portrays Christ’s heart with three blossoming flowers, is inscribed pyte, love, and charyte.

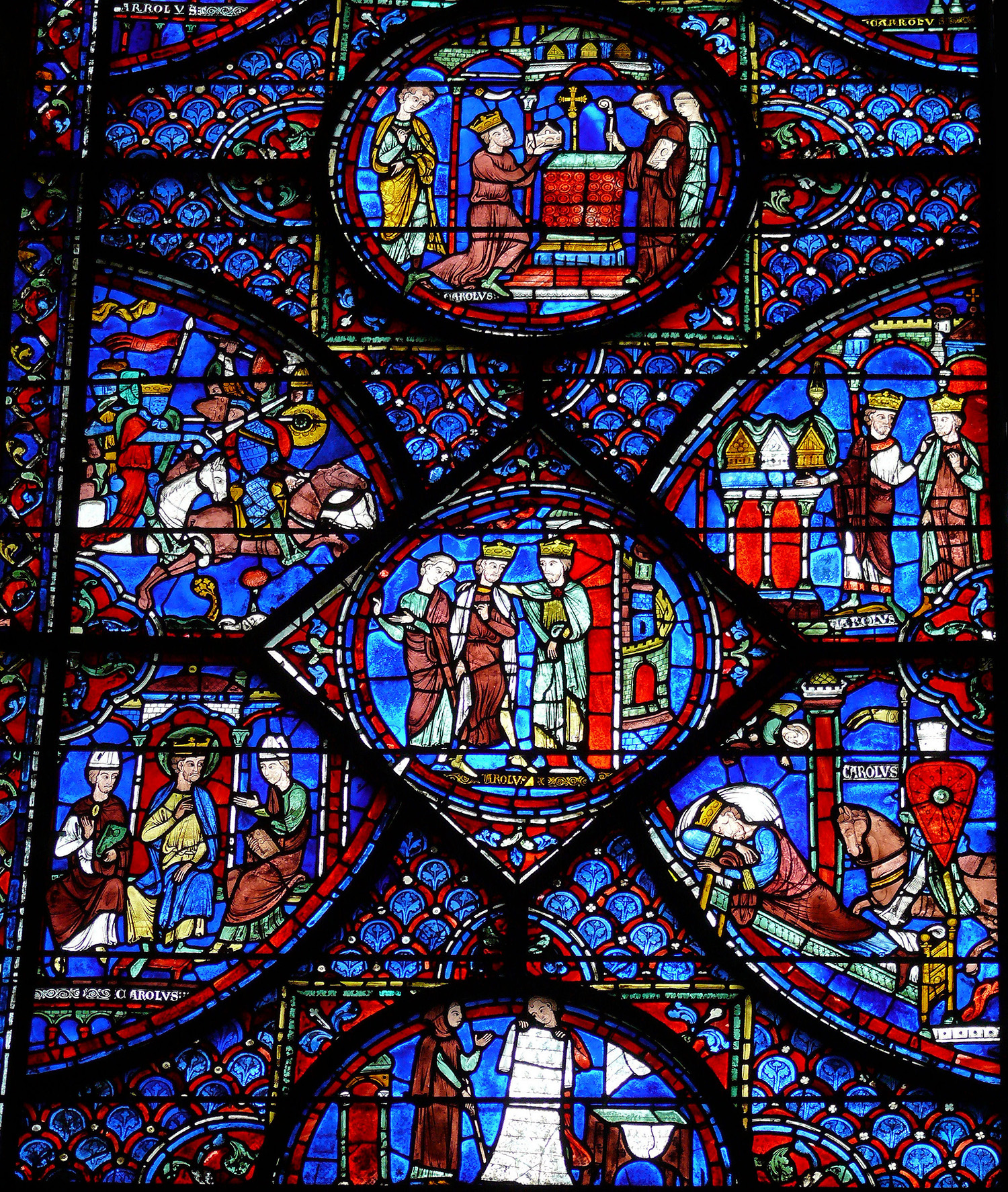

Today marks the feast day of Saint Charlemagne. The Frankish leader was canonized by the antipope Paschal III in 1165, some three-and-a-half centuries after his death on January 28, 814. Political motivations assuredly played a role in this act given the pontiff’s desire to curry favor with Charlemagne’s successor, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Yet it is well worth remembering that distinctly local commemorations of the emperor had already been established throughout the original footprint of the Carolingian empire.

Although Paschal III’s ordinances were officially revoked during the Third Lateran Council in 1179, Charlemagne remained a figure of veneration, particularly in the cathedral of Aachen, which houses an elaborate thirteenth-century shrine containing his relics. On Karlstag, the twelfth-century liturgical chant Urbs Aquensis, urbs regalis is performed within the cathedral in celebration of the emperor’s memory. With its vivid language, the sequence evokes Charlemagne’s accomplishments by describing him as a soldier of Christ, just ruler, converter of infidels, and an all-around rex mundi triumphator. Such descriptors complement posthumous medieval depictions of the emperor, which are amply represented in the Index’s catalogue. Portrayed variously as a ruler, warrior, patron, and saint in different media, these figures of Charlemagne underscore the diversity of guises and legends that developed after the historical emperor’s death.

Shepherd at the Nativity. Fourth century sarcophagus. Arles, Musée de l’Arles et de la Provence Antique, FAN.92.00.2517. Index system number 000107697.

Of all the medieval images associated with the Christmas story, surely most familiar is that of the Nativity, which depicts the Christ child in the lowly stable of his birth, almost always attended by the Virgin Mary, her husband Joseph, and the ubiquitous ox and ass. Medieval nativity scenes often included other onlookers as well, from the shepherds and magi to whom angels announced Jesus’ birth to the midwives who, in some accounts, assisted at it. Of all these figures, few have a longer or more engaging history than the shepherds, with whose homespun character and simple faith many ordinary medieval Christians could identify.

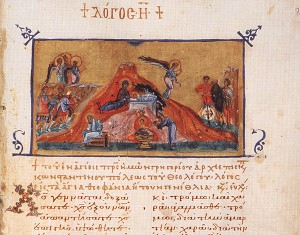

Shepherds and Magi at the Nativity. Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen, 11th century. Jerusalem: Greek Patriarchal Library, MS Taphou 14, fol. 80r. Index system number 150818

The shepherds themselves have biblical origins: Luke 2:8-20 describes them receiving news of Christ’s birth from a host of angels, then rushing to the stable to see the child for themselves. The scene of the angelic annunciation to the shepherds is sometimes presented adjacent to or in the background of the Nativity, and in the very late Middle Ages, under the influence of Franciscan piety, it was also depicted as an independent scene. However, from the beginnings of Christian art, the shepherds were also frequent onlookers at the Nativity itself. By the fourth century, Roman and Gallic sarcophagi had begun to include one or two shepherds standing beside the manger, often raising a hand in recognition of Jesus’ divinity; middle Byzantine mosaics often cast the shepherds as a trio to balance the three magi who also attended the child. Such pairings were encouraged by medieval texts that presented the shepherds as symbolizing the Jewish tradition from which Christianity had sprung and the magi as representing those pagans who converted to the faith. Alternatively, the magi and shepherds were sometimes presented as demonstrating Christ’s recognition by all walks of life, a universalistic message sometimes developed further in the portrayal of both groups as men of varying ages and even ethnicities.

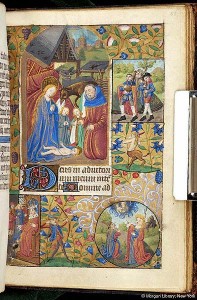

Music-making shepherds on the margin of the Nativity, ca. 1470. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS m.32 fol. 51r, Index system number 000175635

Late medieval pietistic trends, which promoted the idea that the poorest of men had been the first to receive news of Christ’s birth as confirmation of the value of humility and simplicity, encouraged fourteenth- and fifteenth-century artists to elaborate their images of the shepherds. They often are shown as rough-hewn peasant types—sometimes even including a shepherdess—who offer the child simple, heartfelt gifts, such as a lamb, a flute, flowers or, more unusually, a basket of eggs. The appeal of these humane, familiar figures still resonates in many a Christmas sermon as well as Christmas carols, from the traditional Austrian “Shepherd’s Carol” to the 1941 pop hit “The Little Drummer Boy.”

Shepherds are noted in over 650 records of the Nativity in the online database of the Index of Christian Art; many more can be found in the card files. Media include sculpture, gold glass, manuscripts, enamel, mosaic, fresco, and painting. We wish all our friends who celebrate Christmas a joyous and peaceful holiday.

Hanukkah, the Feast of Dedication, also called “Festival of Lights,” commenced yesterday (December 6th) at sundown and will continue for eight days. Hanukkah was celebrated as early as the second century BCE to commemorate the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Under Greek imperial rule, many key Jewish practices had been outlawed and the Temple in Jerusalem was filled with pagan implements. The Hellenization of Jerusalem brought with it the dedication of the Temple to Zeus, the destruction of Holy Scriptures, and many crippling assaults against Jewish custom. The Book of Maccabees recounts the story of Judas Maccabeus, son of the priest Mattathias, and his brothers, who formed a revolt against the Seleucid Empire of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, eventually winning against his heir and successor Antiochus V (See I Maccabees 6). A series of battles ensued from 167 to 160 BCE to reclaim Jewish heritage and freedom to worship in the Temple.

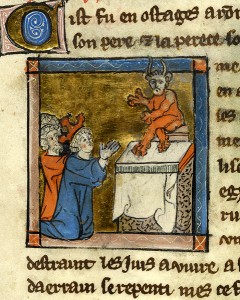

The pinnacle win is classified in the Index under the subject heading, “Maccabees: Battle against Antiochus V” and covers thirteen works of art in the database, mostly in manuscript. Several siege scenes of the Maccabees against Antiochus V armies feature the “Animal: Elephant and Castle” iconography based on the passage in I Maccabees chapter 6. In the passage, Eleazar Avaran runs toward the elephant in royal armor which he believes might harbor the king. In a twist of fate, Eleazar stabs the elephant and it tramples and kills him. Other key Index subjects relating to the history of Hanukkah include, “Antiochus IV: Siege of Jerusalem,” “Antiochus IV: Pollution of Temple,” “Judas Maccabaeus: Cleansing of Sanctuary,” and “Judas Maccabaeus: Altar rededicated.” After the Jews reclaimed the Temple in Jerusalem, it was purified and reconsecrated by the lighting of a multi-branched oil lamp which miraculously burned for eight days; an event which would be marked with the celebration that we now know as Hanukkah.

In medieval times, the growing custom of illuminating the menorah lamp, usually displayed outwardly, fulfilled the rabbi’s decree to confirm the “miracle of lights” to the world. The Index classifies menorah imagery under the subject heading “Candelabrum,” using the keyword “menorah” in a description field. There are 177 database examples in a variety of media including stained glass, sculpture, mosaic, terra cotta, and manuscript illumination.