First in a series of short blog posts introducing the new features of our online database

Did you know that you can search The Index of Medieval Art for information about patrons of medieval art? The Index records both identified and unidentified patrons, the latter entered as grouping terms for types of patrons (Male, Female, Couple) and major monastic orders, such as Augustinian, Benedictine, and Carmelite. There are also general headings for anonymous male and female patrons (Male, unidentified and Female, unidentified). Names of churches, monasteries, and abbeys are given by their proper titles, such as Canterbury Cathedral, but might be further identified by location (e.g. Abbaye d’Anchin [Pecquencourt, France]).

For an overview of our patron headings, click on Browse at the top of the Index landing page. This will bring you to a list of over 900 names and grouping terms sorted in alphabetical order. To reach a specific entry, type the first few letters of a name into the search line at the top of the list. For instance, typing in “Blanche” will bring you to all Blanches from Burgundy, Castile, France, Navarre, and also the late 14th-century Countess of Geneva. Clicking on any patron heading will return a glossary entry comprising a biographical note with dates, alternate names of the patron, a bibliographic citation, an external reference for the authority source, and all the work of art examples linked to that patron.

Our patron entries are formatted in keeping with standard biographical authorities, such as the Library of Congress Name Authority File, the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), and Oxford References. Patrons are identified in the Index database by their roles and dates when these are known. When performing an Advanced Search in the “Terms” screen, you may prefer to keep the Match Type set to “Default,” which will search all parts of the heading. In the “Terms” window, a search can be formulated with keywords such as “Pope,” “Doge,” or “Prince,” using “Patron” in Search Fields to locate medieval patrons by their role. Similar keywords, along with keywords for place indicators like “Monastery” or “Convent,” can be searched against the “Patron Note” field, which will search the biographical notes in the patron glossary.

Many of the monastic patrons contain their locations in parentheses after the name of the community, so countries of patronage activity can also be searched as keywords. For instance, searching against “Patron” or “Patron Notes” with the keyword “Italy” returns over 150 records. This indicates artwork results for a patron who was active in Italy. From here, in the “Filters” window, the Date Slider can be used to refine results. The “Terms” search can be refined with any of the additional filters, including “Location,” “Medium,” “Style/ Culture,” and “Work of Art Type.”

Are you interested in finding out which female patrons were active in France in the 14th century?

In the Advanced Search “Terms” screen, enter the keyword “Female” and choose the Search Field “Patron” (keeping Match Type set to “Default,” as recommended).

Then, go to “Filters,” select “France” as a Location, and set the Date Slider to 1300 and 1399. This search should yield 27 examples, where a female patron is connected to the 14th century work made in any part of France.

*In results, please note that work of art records will include Main records indicated with a logo picture.

As you search for patrons in the new Index of Medieval Art database, bear in mind that visual representations of patrons are found in the Subject field. To find images of patrons, you can browse or search the Subject field with the keyword “Donor.” To read more about medieval patronage practices in general, you might find the Index’s 2013 conference publication Patronage, Power, and Agency in Medieval Art of interest. Enjoy refining your searches and browsing the range of patrons we record in the Index! And please remember that we are always happy to have your feedback. Get in touch with us at theindex@princeton.edu.

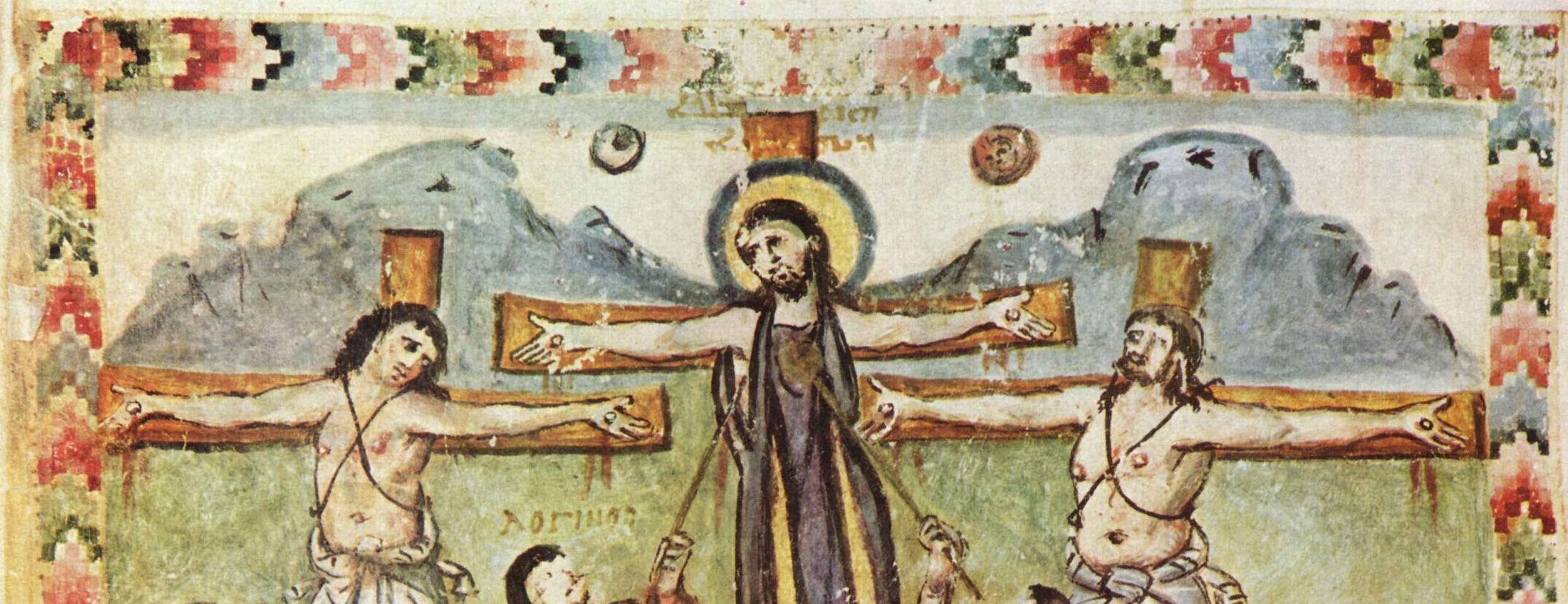

Matthew’s Gospel tells us that, at the moment Christ died, darkness swept over the land for three hours (Matthew 27:45). The foreboding skies at Christ’s crucifixion were also recorded in Luke 23:44-45 and Mark 15:33. Mark’s account, thought to have been written around the year 70 CE, was likely the earliest.[1] Some scholars have reasoned that this midday phenomenon was an actual eclipse, because the passage in Luke reports that darkness fell over the land when “the sun was eclipsed” (“τοῦ ἡλίου ἐκλιπόντος”) (Luke 23:45). However, the passage is usually translated “the sun was darkened.” The verb is in the passive voice, as is the verb “ἐσκοτίσθη” used in other versions of the Greek text, and both words can mean “was darkened” or “was obscured.”[2] No matter how we may interpret the words relating the phenomenon, and no matter whether it is possible to attribute the darkness thus described to a real astronomical event, scriptural hours of daytime darkness over Golgotha presented an iconographic opportunity to medieval artists depicting the Crucifixion.

In manuscripts and painted works of art that aimed to depict the event, color was frequently exploited to illustrate darkness and to create a dramatic setting. Across media, the celestial bodies of the sun and the moon were incorporated into the skies above the crucifixion, not only to signal darkness at daytime but also to imbue the scenes with a rich cosmological significance.

An especially early example appears in the Syriac Rabbula Gospels from the late sixth century. In this manuscript, the Crucifixion includes a partly eclipsed Sun and a Moon with a face against a remarkably light sky; a sliver of shaded pigment at the top suggests darkness (Figure 1). From antiquity, the sun and moon were associated with power. In early medieval crucifixion scenes they represented God’s cosmic anger at the death of Christ.[3] Throughout the Middle Ages, personifications of the Sun and Moon became regular characters at the Crucifixion, positioned as sorrowful figures mourning Christ’s death. The placement of the Sun and Moon respectively at the right and left arms of the cross came to be read typologically as the Old and New Testaments.[4] After about 850, they could also be seen as allegorical representations of Church and Synagogue.[5]

The Ottonian Sacramentary of Henry II sets the Crucifixion scene against a deep purple background, a striking hue used to set a somber mood and suggest darkness (Figure 2). Busts of the personifications Sun and Moon sit on the arms of the cross. The Sun, labeled SOL and sporting a rayed headpiece, and the veiled Moon, labeled LUNA, both turn away from the scene and weep into their draped hands. The strong background color effectively conveys the darkness of this scene emphasized by the dramatic gestures of the Sun and Moon.

Medieval artists sometimes set the same iconographic features within a flattened space of gold or patterned backgrounds. A leaf from the Potocki Psalter, made in Paris in the mid-13th century, sets the Crucifixion against a gold background (Figure 3). Christ is flanked above by the sun and moon and below by the Virgin Mary and the Evangelist John. Within this composition, the three main figures hover between time and space, darkness suggested only by the presence of the partly obscured sun and the crescent moon.

Similarly, in a Crucifixion scene painted around 1400 to 1410 in a Register of Coiners and Minters from Avignon, a richly patterned background of gold scrolls avoids any illusion of a dim sky (Figure 4). The red sun and the moon’s countenance in the upper corners of the miniature are the only clues that the ornamental ground is actually simulated “darkness.” In both miniatures, decorative and luminous backgrounds highlight the central features of the scene so that the Crucifixion image becomes a place of mediation, the background “darkness” metaphorically positioned between an earthly space and a shift in the cosmos at the moment of Christ’s death.

Images of darkness at the Crucifixion can be found in the Index database by any of several possible search strategies. One method is to perform an advanced search using the keyword “Crucifixion” while filtering with the subject “Sun and Moon.” This search returns over 380 results. Executing the search again with the subject “Personification: Sun and Moon” returns around 220 examples in a variety of media, including ivory plaques, glyptics, and frescoes. “Personification: Sun and Moon” is the subject used by the Index for records concerning works on which both celestial bodies have facial features. Using words like “stars” or “starry,” background elements that can also suggest a dark sky may be recorded in the Index’s descriptions of such works.

With the advent of the Index of Medieval Art’s new database, thumbnail images are now visible with search results, allowing the researcher to review works of art at a glance. Thus, a researcher looking into images of the Crucifixion will be able to notice the gradual change in the later medieval period in the West, when images of the Crucifixion began to represent the three-hour darkness as a true night sky. In a Book of Hours made in Paris about 1490, a soft pattern of gold stars with the sun and moon dot a dark blue sky to create the illusion of evening (Figure 5). Other Crucifixion scenes that a researcher may notice while thumbnail browsing show cloudy, dark, and emotive skies that convey darkness without the sun or moon. These atmospheric scenes offer a remarkable and naturalistic, if not peaceful, departure from the earlier ones with their grief-stricken personifications of the Sun and Moon.

The starry night sky casts a familiar source of light over a recognizable scene, and these astronomical bodies inspired fascination in medieval minds still forming theories about what those bodies might actually be. Nevertheless, the symbols of the Sun and Moon, while signaling darkness and the passage of time, also imparted emotional weight, persisting in iconography not only to adhere to scriptural tradition, but also to emphasize the significance of Christ’s death.

Further Reading

Hautecoeur, Louis. “Soleil et la lune dans les crucifixions.” Revue archéologique, ser. 5, XIV (1921): 13-32

Schiller, Gertrude. “The Crucifixion.” In vol. 2 of Iconography of Christian Art, 88–164. London: Lund Humphries, 1972.

Nickel, Helmut. “The Sun, the Moon, and an Eclipse: Observations on The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, by Hendrick Ter Brugghen.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 42 (2007): 121–24.

[1] The Gospels report three other supernatural events that occurred during the Crucifixion: the temple veil was split in two; various earthquakes shook the land; and the souls of the dead rose from their graves. See related subjects in the Index of Medieval Art: Christ: Crucifixion, Earthquake; Christ: Crucifixion, Resurrection of Dead, and Veil of Temple: rending.

[2] Bible Translation. “David Robert Palmer trans., The Gospel of Luke: Part of The Holy Bible.” Accessed 30 March 2018. Bibletranslation.ws/trans/lukewgrk.pdf. See especially p. 116, n. 307.

[3] Gertrude Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, trans. Janet Seligman (London: Lund Humphries, 1972), 2:94.

[4] This interpretation was promoted by St. Augustine (354–430 CE). Schiller, 109.

[5] Schiller, 110.

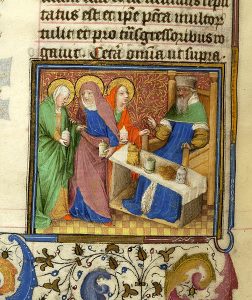

Throughout the Middle Ages, the feast of the Presentation of Christ was observed on February 2nd, where it gradually absorbed the rites of the Purification of the Virgin.[1] Incorporating blessed candles and certain songs, the feast came to be known as Candlemas. The only gospel writer to describe the Presentation of Christ in the Temple was Luke in the second chapter of his Gospel account (Luke 2:22–39). Luke writes that, in accordance with Jewish tradition, parents were required to bring an acceptable offering in exchange for the priest’s redemptive blessing on their child. Luke notes that “a pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons” would fulfill the sacrifice (Luke 2:24). In Presentation scenes, the gathered doves, usually held by Joseph, signal Christ’s restoration under Mosaic Law. Over time, lit candles at this same ritual came to mark the Virgin’s cleansing and reentry into the temple.[2] In a stained-glass window in Canterbury Cathedral, we find Joseph holding both implements at the far left, a visual sign of the combined purpose of their visit (Figure 1).

When the Holy Family approaches the altar, Luke records two mystical occurrences that concern key witnesses in the temple. First, Simeon, the named priest from Jerusalem, prophesies the divinity of the Christ Child.[3] Another prophetic utterance comes from the lips of an unlikely source, the temple’s aged widow, Anna the prophetess. Luke tells us that Anna fasted and prayed there without ceasing. Anna is the New Testament’s only prophetess, and her privileged glimpse of the important ritual uniquely connects her to the childhood of Christ.

The Presentation is Anna’s one shining moment in the Gospels. In the Index of Medieval Art there are over 960 examples of the subject Christ: Presentation, and at least 330 include Anna as a secondary figure in the scene. We discover varied depictions of Anna in these medieval images. She is depicted as a scroll-bearing prophetess; as proxy to the presentation ritual, handling the different ritual items; or she may be simply shown among the other women surrounding the Virgin Mary. Despite her prominent role at the Presentation of Christ, Anna’s portrayal in medieval images can be perplexing. It seems medieval artists, who knew about her visionary role at the Presentation, could choose to emphasize or de-emphasize Anna as a prophetess based on tradition, context, or perhaps even their own interpretations of her significance. Several Presentation scenes also include a woman near the altar, and Indexers have often identified her as a female attendant, questioning her identity as the prophetess in iconographic descriptions.[4] Thus was born the usual Index reading of this female figure: “probably Anna.”

Because of the inconsistency of representations of the Presentation, it is not always easy to identify Anna in medieval images. Moreover, Luke’s account offers few details about her, other than that she is:

Analysis of Presentation scenes does reveal a few key details consistently associated with Anna: the presence of a halo; her scroll, which expounds her part in the prophecy; her interaction with presentation/purification implements, including the doves and candles; and her advanced age, sometimes suggested by her modest wimple. One or more of these details could be enough for a positive ID of our prophetess. Another sign is her speaking gesture, as in the Presentation miniature in the Romanesque Mont-Saint-Michel Sacramentary, in which Anna’s hands are shown outstretched in a wide statement of praise (Figure 2). This miniature also exemplifies an iconographic conundrum that sometimes accompanies Anna: a second nimbed and veiled female figure stands just behind Joseph, and she is carrying two doves in draped hands. Is this a second Anna? Or is this simply a sanctified female attendant? This female assistant is doing what many later Annas do in bearing the sacrificial birds, so the context with which we identify Anna becomes increasingly important.

Anna is one of the first people, even the first woman, to reveal Christ’s destiny, but her exact words are omitted from Luke’s account. We know that she “spoke of him to all that looked for the redemption of Israel” (Luke 2:38). However, since Anna’s actual words are not recorded, her scrolls present a number of different inscriptions. An Index search reveals some of the most intriguing ones. In the fifth-century sanctuary apse mosaic at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, Anna’s scroll is inscribed BEATVS VENTER QVI TE PORTAVIT (Luke 11:27), meaning “Blessed is the womb that bore thee.” In a late twelfth-century mosaic in the Cathedral of Monreale, Anna holds a scroll inscribed POSIT(US) EST HIC I(N) RVINA(M) (Luke 2:34), repeating the words first said by Simeon, “This child is set for the fall.” In a fifteenth-century panel by the artist known as the “Byzantine Painter,” Anna holds a scroll inscribed (in Greek) “This child created Heaven and Earth” (Figure 3). And in one emotive declaration in a ca. 1240 Psalter from Hildesheim, Anna’s scroll is inscribed in Latin, EXULTATUIT COR MEUM (I Samuel, 02:01, also known as the Canticle of Anna), meaning “My heart hath rejoiced” (Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. Don. 309, fol. 37r).

Anna’s scroll has even been used to identify her by name, as in the presentation scene on the ca. 1365 Florentine Ashmolean Predella, from a private collection in Tuscany, with a scroll inscribed “ANNA PROFETESSA DEO GRATIAS AMEN” (“Prophetess Anna, Thanks be to God”). In this case, Anna’s index finger is elegantly lifted upward to indicate from whom her proselytizing originates. In other examples, Anna’s scroll can be completely blank, or filled with a pseudo-inscription. In the Armenian T’oros Roslin Gospels, the scroll expands into neat folds revealing simple red rulings (Figure 4).

The new advanced filter options offered by the Index database can reveal interesting trends within the Anna images recorded by the Index. I performed a keyword search for “Anna,” filtering by the subject Christ: Presentation, and restricted the search to fifteenth century examples (setting the date slider at 1400 to 1499). I limited these examples further with the Work of Art Type filter set to “Manuscript.” This way, I found over 60 records of interest describing fifteenth century illuminations that include this scene.

I narrowed these results further by adding a second subject filter with one of the Index’s grouped terms, Candle: held by Prophetess Anna. I found that, with each refinement, I was able to reconstruct Anna’s changing representation in medieval iconography. Curiously, in several of these late medieval examples, Anna is holding both a candle and a dove, and she is directly behind the Virgin Mary (not Simeon), displacing Joseph completely. These three-character scenes of the Presentation make up a good portion of later examples, and they underscore Anna’s union with the Holy Family’s first official appearance. In one such image, a fifteenth-century Book of Hours made in Paris, Anna is holding a candle in her right hand while playfully balancing a basket of birds on her head. A talented multitasker, Anna has, in a sense, usurped Joseph’s gift-bearing role (Figure 5).

No matter how she appears—as a wise widow bearing her scroll, or as a female witness bearing the implements of the impending ritual—the prophetess Anna is an exemplary New Testament woman. Through her time-honored vows of chastity, piety, and obedience to God, virtuous qualities brought out in her varied iconography, she presents a model of behavior for the young mother.

Further Reading

Shorr, Dorothy C. “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple.” The Art Bulletin 28, no. 1 (1946): 17–32.

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art, vol. 2, The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, trans. Janet Seligman (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1972): 90–94.

Elliott, J. K. “Anna’s Age (Luke 2:36–37).” Novum Testamentum, 30, Fasc. 2 (Apr., 1988), 100–102.

Hammond, Joseph. “Tintoretto and the ‘Presentation of Christ’: The Altar of the Purification in Santa Maria Dei Carmini, Venice.” Artibus Et Historiae 34, no. 68 (2013): 203–217.

“Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple.” In The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art & Architecture, edited by Murray, Peter, Linda Murray, and Tom Devonshire Jones: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Witherington III, Ben. “Mary, Simeon or Anna: Who First Recognized Jesus as Messiah.” Accessed 2 February 2018: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/mary-simeon-or-anna-who-first-recognized-jesus-as-messiah/

Notes

[1] From at least the fourth century this ritual was celebrated as a post-purification feast, known as Hypapante, which Justinian set 40 days after the feast of the Epiphany, or on February 14.

[2] For the best study of the development of this iconography, see Dorothy C. Shorr, “The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple,” Art Bulletin 28 (1946): 20–46.

[3] Simeon holds the infant in his arms and instantly says to the Virgin Mary, “Behold this child is set for the fall, and for the resurrection of many in Israel…,” and representations of Simeon are associated with the text Nunc Dimittis, also known as the Canticle of Simeon (Luke 2:34–35).

[4] Shorr notes that, in most northern medieval examples after the thirteenth-century, Anna’s place was taken over by a young handmaiden (Shorr, 1946, p. 27).

The Index of Medieval Art is proud to announce that the new database platform is now in beta. Project Phoenix is the culmination of years of planning and development in collaboration with Luminosity Labs. When we first conceived this project in the summer of 2014, we decided that we needed to develop a platform that was modular enough to build upon in the future. It was important to us that, as methods of study change, the tools we provide researchers must be able to evolve as well.

There are now more access points into our data. Our new advanced search and refinement tools will give our users much greater flexibility, so that results can be narrowed to isolate specific works of art. Users will now have the ability to target their queries with multiple factors—such as date, location, subject, media, and more—but with precise control.

The new platform also introduces a responsive design, meaning that the user interface can adapt to your device whether it is a large computer monitor or a smaller tablet. We estimate as much as 50% of our web traffic is from mobile devices such as iPads, so we are working to make sure that we can support the mobile experience.

This is just the start: we will be rolling out many additional features over the next few weeks and months. In the coming year we plan to introduce a new interface for navigating in situ works, as well as a new interface for exploring our subjects by hierarchical classification rather than keywords alone.

In 2018, we will also be implementing IIIF support for images. This will mean that works of art for which we have high-resolution images can be examined in greater detail. You will have the ability to zoom in and out, and to pan around the images, all from within our web application.

We invite you to try out our Project Phoenix beta to see what we’ve been working on. And please send us your feedback! We welcome your thoughts, but keep in mind that this is the beta stage of development, so not everything is working perfectly yet. Some features have not been fully implemented, and some may be disabled from time to time while we work to improve them.

In the meantime, the old, familiar database is still available to subscribers. This legacy database will continue to be available until we are comfortable that the new version can supersede the old one completely.

Thanks for your support and patience through these exciting times. We look forward to hearing from you about the new design!

The personification of Wisdom in medieval art is usually grouped with other virtues, such as Justice, Hope, Prudence, Chastity, Poverty, Courage and Fortitude. While she works in communion with these sisters, she also performs her own distinct role. As the story goes, Wisdom was created by God before the world existed and is therefore in the position to offer humanity knowledge that will lead to its salvation. When Wisdom speaks in the Book of Proverbs, it is often to highlight her own importance and power. She calls herself a font of knowledge and a righteous helper who will reward those who follow her instructions. Wisdom says,

“By me kings reign and lawgivers decree just things. By me princes rule and the mighty decree justice. I love them that love me, and they that in the morning early watch for me shall find me. With me are riches and glory, glorious riches and justice….” [Proverbs 8.15–18 (Douay-Rheims Bible)]

This reward of Wisdom manifests in two ways: not only does she assist in saving the souls of those who heed her message, but she also has the authority to grant earthly power to individual rulers. The Index of Medieval Art records several scenes in biblical and secular narratives in which the virtue of Wisdom is a central character. Some relevant subjects in the Index include Christ: praising God’s Wisdom; Personification: Holy Wisdom; Personification: Celestial Beatitudes; and Holy Ghost: Gifts; and in narratives, Pèlerinage: Scene, Wisdom with Aristotle; Confessio Amantis: Scene, Darius, Sultan of Persia, seeking Wisdom, and De Consolatione Philosophiae: Scene, Wisdom showing Boethius Vision of Heaven.

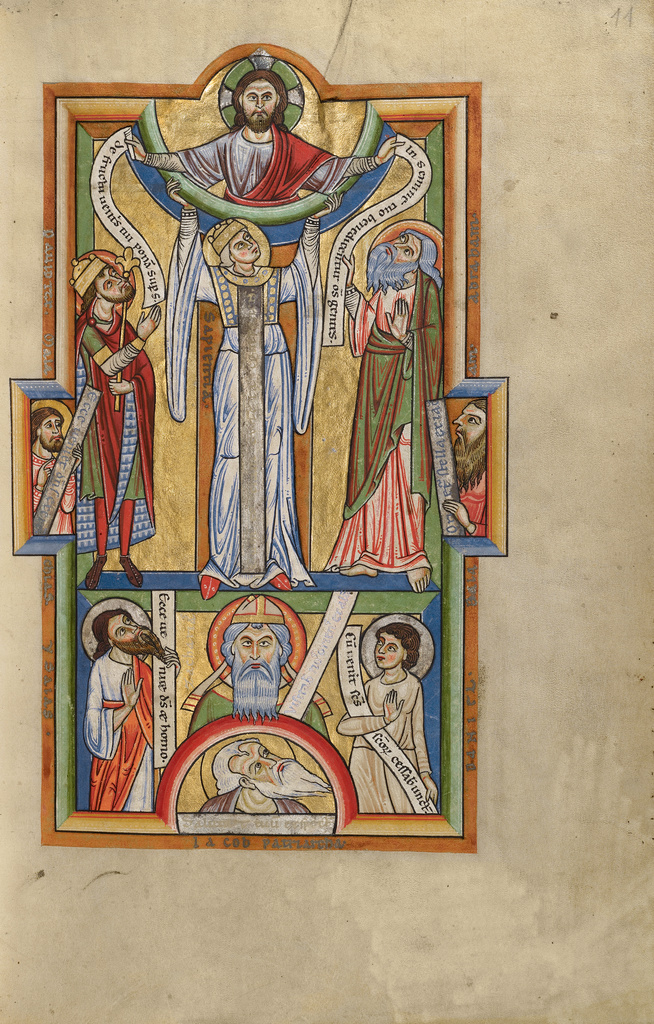

In some Semitic languages, the word we translate as wisdom literally meant to restrain oneself from evil, suggesting a conscious desire to avoid sin. Thus, a sinful individual cannot approach Wisdom, as illustrated in a Romanesque miniature on folio 11r in the Stammheim Missal made in Hildesheim [Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 64 (97.MG.21)]. Flanked by David and Abraham, a crowned Wisdom (Sapientia) is positioned beneath the half figure of Christ. Here she is in direct contact with the divine as she supports with raised hands the arc of heaven, the traditional separator of realms. In a sense, she has become a gatekeeper and mediator for Christ. Surrounded by earthly men, including Zechariah and Patriarch Jacob, Wisdom can also be seen as a kind of “ladder” to heaven, since her upright body forms an important link to the promise of salvation.

Wisdom’s spiritual authority is exemplified by a scene on folio 239v of the De consolatione philosophiae of Boethius, which shows her leading the Roman philosopher to God’s throne (New York, Morgan Library, M.396). They enter through a side door of the throne room, positioning Wisdom once again as the route to the divine.

However, Wisdom also bore earthly authority, mentoring influential individuals such as Solomon, the Old Testament king of Israel and the traditional author of the biblical Book of Wisdom. This relationship is illustrated within an initial P (New York, Morgan Library, M.791). Against an ethereal gold burnished background, a veiled Wisdom crowns Solomon as a sign that she is at the root of his authority. By Wisdom—and by way of Wisdom—Solomon enacts what is so eloquently echoed in the verse of Proverbs: he will enjoy elevated status owing to the receipt of spiritual gifts; his reign is received in righteousness; and his rule is just.

This guest blog post was written by Rachel Dutaud, a summer student assistant at the Index of Medieval Art and a recent graduate in Art History and Ancient History from the University of St. Andrews. Over the 2017-18 academic year, Rachel will be working toward her MA degree in Archives & Records Management at University College Dublin. Her interests are medieval art history, iconography of female rulers, classicism, and archives.

One of the little thrills those us who do academic research get to enjoy — whether we specialize in the arts and humanities or engineering and sciences — is when our favorite topics come up in films or on television. Imagine the excitement for anyone who studies Andalusian architecture when the quasi-medieval show “Game of Thrones” received rare permission to film inside the beautiful Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain.

Now perhaps it will come as no surprise that several of us here at the Index of Medieval Art are looking forward to the next series of “Doctor Who” — and the premiere of the first female Doctor (to be played by Jodie Whittaker)! — when the Doctor’s complicated history with historical accuracy resumes. For those of you regrettably unfamiliar with “Doctor Who,” it is a long-running BBC show about a long-lived, possibly immortal, time-traveling alien, and history nerds are among the most avid Whovians. To understand why, just watch the episode in which Pompeii was destroyed because aliens were building a spaceship in Vesuvius! In another episode, we learned that William Shakespeare’s plays include secret spells that open portals to other parts of the universe!

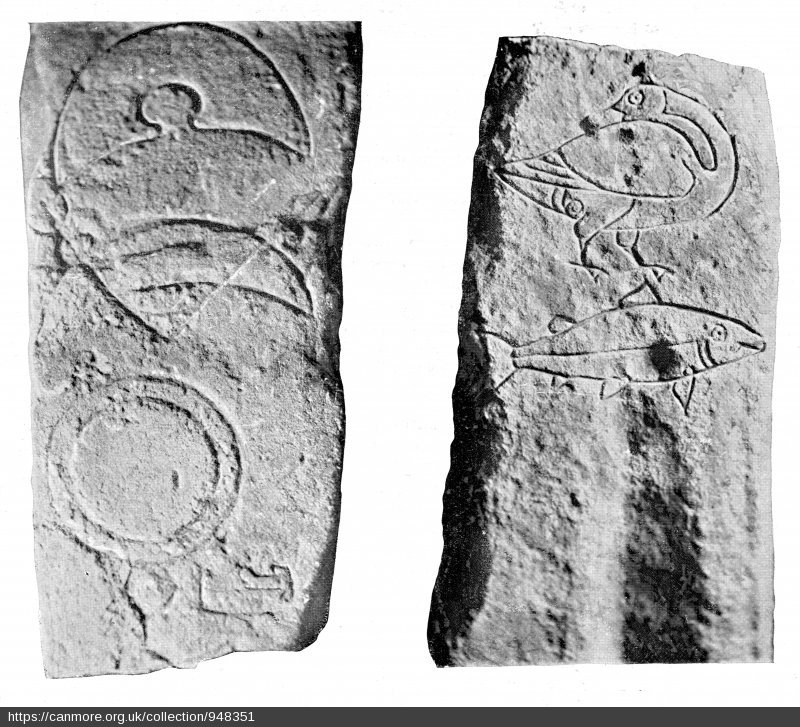

In the most recent series, the episode “The Eaters of Light” took place in Scotland in the second century AD. The Ninth Roman Legion, charged with the task of defeating the “barbarians” living in ancient Scotland, disappeared without a trace. When the Doctor and his companions investigate, things get a little strange. In the second century, the Roman Empire was trying desperately to maintain control of the lands of the “Picts” who lived north of what would very soon be the site of Hadrian’s Wall. The Picts are so called because these “painted people” (Picti) are mentioned in very early medieval texts. We know almost nothing about them, other than that they were fierce warriors, they painted their bodies before battle, and they left behind large stone monuments decorated with pictographic writing.

The Index of Medieval Art has almost 250 entries for “Pictish” artwork, most of which are large stones, either stelai or crosses. The stones usually appear in pairs, and the symbols carved on them depict inanimate objects like mirrors and combs, or crescents, and other geometrical shapes, as well as animals such as horses, dogs, birds and the enigmatic “Pictish beast.” It was this Pictish beast, a creature something like a hybrid of dolphin, horse, and dragon, or even (as some have argued), the Loch Ness Monster, that was the focus of “The Eaters of Light.” The episode proposed that it was a species of lizard-like alien monster that traveled through a great stone chamber-tomb in northern Scotland. Released in order to defeat the invading imperial army, it continued eating, threatening to consume all the light in our universe. Of course!

While this episode provides a fanciful interpretation of the Pictish stone carvings, it does actually highlight a point that art historians and archaeologists have been puzzling over for more than a century — just what do these symbols mean?

The stones were classified in the early twentieth century into three types, based upon their iconography and the level of detail in their carving. Class I stones, which date roughly to the fifth to seventh centuries, are relatively plain, and have only Pictish symbols inscribed upon them. Class II stones are slightly more ornate, with more effort obviously spent on not only carving the imagery but also on decorating the shape of the stone itself. They have not only Pictish symbols, but also Christian iconography such as very simple cruciform carvings. These are thought to date to the period of the seventh to ninth centuries, when conversion to Christianity was becoming more common in the region we now know as Scotland. Finally, Class III stones, which date to the later eighth and ninth centuries, are the most ornate. Their edges are highly decorated, the shape itself has been clearly hewn from the rock rather than simply incised upon it, and they have intricate carvings of knot-work and lace-work. Apparently used not only as upright markers or crosses but also as grave slabs, all of these Class III stones have explicitly Christian imagery, with many carved in the shape of crosses. None of them bear Pictish symbols, so these stones are interpreted as a last step in the Christianization of Scotland.

There are, however, two main difficulties in interpreting these Pictish symbol stones, though there are many theories as to what they represent. First, we are not entirely sure what they were for. Scholars have debated the issue for the last half century, arguing that they were monuments marking important meeting places or boundaries, or that they were memorials to particular individuals, families, events, or even that they might have been political statements opposing the spread of Christianity in early medieval Britain. Inscriptions are not helpful for interpretation either. While ogham writing in Ireland and Wales is found on stones that include Latin inscriptions, so that each stone is like a Rosetta Stone (with the Latin inscription in each case serving as a key to interpreting the ogham text), we do not currently have such a direct method of interpreting Pictish ideograms.

The second problem is the dating. Surviving Pictish stones suggest a development from the simple, presumably pagan, Pictish animals and shapes of Class I stones to the elaborate crosses in Class III. Like much archaeological evidence from the post-Roman fifth and early-sixth centuries in Britain, this dating is often based upon our expectations affected by early medieval texts like Bede’s Ecclesiastical History or Gildas’s On the Ruin of Britain, none of which were written in Britain in the period they describe. Unlike human or plant remains, stones cannot be radiocarbon dated. Even if we wanted to make the attempt at dating, for example, organic elements of the soil beneath the stones, only a few of the stones are actually still in situ. So the dating of the Pictish stones depends on parallels in manuscripts such as the Book of Durrow, and upon what we currently think about the history of the arrival of Christianity in Scotland. Even if we were able to determine with absolute certainty when exactly these stones were first inscribed and placed in the landscape, that account would still not consider the many succeeding generations and their many possible uses for these stones.

The Pictish stones in the Index of Medieval Art, especially the Class I stones, are part of a wider discussion of very early medieval society in Scotland. The Picts are the people that sixth-century and later texts blame for the beginning of the end of Roman Britain. Their raids along coasts to the south created defensive problems at a time when the Roman military presence in Britain was declining. Over the last fifty years or so, archaeological excavations of cemeteries in Scotland have increased our understanding of the monumental commemorations of death among the people who raised these decorated stones and crosses. The iconography on the stones that these people left behind is one of the few sources that modern scholars can work with to learn about the Picts and their world — and it also turns out to be a great source of inspiration for science fiction television.

This guest blog post was written by Janet Kay, a CLSA-Cotsen postdoctoral fellow at the Princeton Society of Fellows. She studies the history of fifth-century Britain, looking at burial practices to study a period for which there are no surviving texts. Janet uses material culture and funerary rites as primary sources to explore how fifth-century communities understood themselves and their newly-arrived neighbors from the continent and how invested they were in maintaining connections with their Roman past.

The month of June marks the passing of two historically consequential rulers: the fourth-century Roman emperor Julian, posthumously referred to as Julian the Apostate, and the twelfth-century Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, also known as Frederick Barbarossa. Their untimely deaths shocked the Late Antique and Medieval worlds, respectively. On June 26, 363, Julian was mortally wounded in the battle of Samarra during a Roman military campaign against the Persians. According to various sources, a spear delivered by a member of the Sassanian cavalry pierced his liver, and he subsequently died from the mortal blow some three days later. June 10, 1190, marks the day on which Frederick Barbarossa drowned in the Saleph River (the Göksu in modern Turkey) in the middle of the Third Crusade, the Latin West’s attempt to recapture the Holy Land from Saladin. The deaths of both leaders in the middle of critical military campaigns generated either anxiety or derision among their contemporaries, as underscored in subsequent medieval representations of the two emperors.

Posthumous medieval representations of Julian, the last Roman emperor who championed paganism, are almost always critical. For example, a lavishly illuminated ninth-century Byzantine manuscript of Gregory Nazianzen’s homilies (Paris, BnF, gr.510, fol. 374v), depicts the ruler accompanying the pagan philosopher Maximus of Ephesus and venerating idols. In Simone Martini’s fourteenth-century fresco cycle in the Chapel of Saint Martino within the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi, the figure of Julian the Apostate serves as an arrogant, pagan, visual foil to the saintly Martin of Tours, who is shown renouncing military life for his Christian beliefs. Depictions of Julian’s death are even more damning. By the early sixth century, accounts surrounding Julian’s death shifted away from a battle against the Persians and amplified the legend of Saint Mercurius (identified as Mercurius of Caesarea in the Index database), a Byzantine soldier saint who rises from the dead and kills the pagan emperor with his lance or sword.

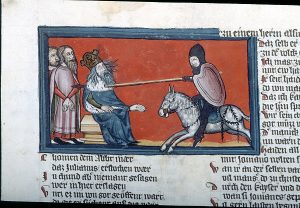

Although this legend developed in Eastern sources, it grew in popularity in the Medieval Latin West, even making an appearance in Jacopo de Voragine’s thirteenth-century Golden Legend. In a fourteenth-century Christherre-Chronik miniature in the Morgan Library (New York, PML, M.769, fol. 327v), the figure of Julian is portrayed as an elderly medieval monarch lanced by a fully armored Saint Mercurius astride a galloping horse.

In contrast to the overwhelmingly uncomplimentary medieval portraits of Julian the Apostate, representations of Frederick Barbarossa generally evoke the idea of imperial majesty and power. The so-called Cappenberg head (c. 1160), a reliquary that originated as a portrait of Frederick, effectively conveys an image of grandeur and stability through its precious materials and antique visual language. Yet a miniature drawn, less than a decade after his death, in Peter of Eboli’s De Rebus Sicilis (Bern, Stadtbibliothek, 120 II, fol. 107r) betrays the unease surrounding the emperor’s accidental passing. Inscribed FREDERICUS IMPERATOR IN FLUMINE DEFUNCTUS, the drawing depicts the ruler falling off his horse and drowning in the water, his crown lying ignobly in the riverbed. As if to combat the contemporary whispers that Frederick died without confessing his sins, the illuminator purposely included an image of the ruler’s soul as a swaddled infant held aloft by an angel and given to the Hand of God emerging from heaven. In so doing, the artist was participating in a larger, concerted effort to salvage Frederick Barbarossa’s reputation for posterity as a noble and most Christian emperor.

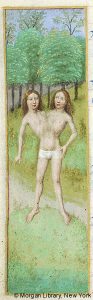

While the other months of the year had specific harvesting tasks associated with them, the relative ease of May was a welcome relief from the daily toil that dominated medieval life. May occupations are traditionally represented as more joyous, particularly in Books of Hours and Psalters. The Index database records over 180 scenes for May in manuscripts, and a little over half of them use the occupation of the male falconer on horseback (see related subjects: Month, Occupation: May; Figure, Male: Falconer; Horseman: Falconer; and Scene, Sports and Games: Falconer). Falconry, or Hawking, was a favorite medieval sport enjoyed especially at the beginning of spring. These hunting birds were prized for their agility and loyalty to their masters. Another popular scene depicting May is a pair of lovers on horseback, occasionally with a bird perching on the man’s wrist. This scene of a riding couple was a favored occupation and signaled the readiness for new courtships. Other instances of May scenes include figures holding flowers or wreaths, couples promenading, and other verdant scenes of courtship, whether amid blooms in grassy gardens or even on boats (see related subject: Scene, Secular: Courting).

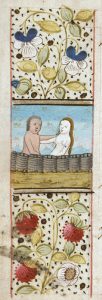

The zodiac sign that commences in May is Gemini, traditionally represented by a pair of figures—Gemini being Latin for “twins”—that are linked to their astrological appearance in the sky (see related subjects: Zodiac Sign: Gemini and Constellation: Gemini). The representations of Gemini can also be divided into a few main categories. A sample of about 80 French medieval manuscripts reveals that the most popular Gemini sign was the embracing nude couple, with far fewer of them appearing clothed. Often the couple’s bodies are masked by parts of the landscape or are cropped by a frame. Nude twins are the second most common Gemini sign and are usually depicted as two men embracing or wrestling. Sometimes the twins will appear as confronted soldiers with mirrored weapons and gear. The twin variations in Gemini also include pairs with crossed legs, conjoined bodies, or even one figure with two heads.

The subjects for months and zodiac signs are most prevalent in manuscripts, but they are also well-represented in sculpture such as the famous façades at Chartres and Vézelay. In 2007, information on all zodiac and occupation subjects classified by the Index was collected and published with Penn State University Press as Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months and Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art. This book has been hailed as a “lavishly illustrated” and “functional research tool” for studying the subject of the medieval measuring of time.

Hourihane, C., ed. Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months and Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2007.

Neal, K. “Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months & Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art (review).” Parergon, vol. 25 no. 2, 2008, pp. 164-166.

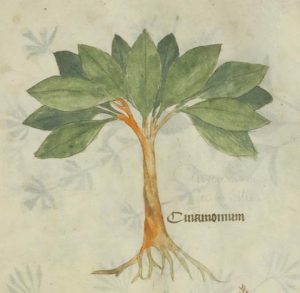

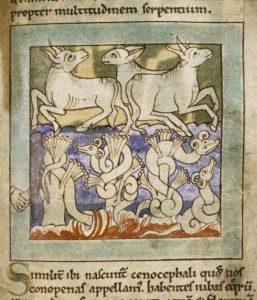

The marketplaces of medieval Europe were redolent of the spices that purportedly first arrived with returning Crusaders. A taste for the flavors of cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, ginger, pepper and the like created an increasing demand for spices that could not be grown in Europe’s climate but had to be imported from the East along secret trade routes, over land and sea. Distance was only one of several factors that affected the supply of spices, which were expensive and enjoyed only by those who could afford them. Nevertheless, as Paul Freedman writes in his blog “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced our World,” the new taste for exotic flavors helped encourage world exploration and turn spices into global commodities.

The uses of spices were both culinary and medical, and medieval cookbooks and herbals reveal that spices were part of preferred regimens. Spices were taken together in varying combinations, sometimes seasonal. In the cold and wet winter months, it was advisable to eat spices in strongly flavored food and drink to warm the body. Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat notes in her History of Food that the physician Arnau de Villanova (c. 1240-1311) recommended balancing the four humors of the body by consuming spices “proper for winter” as zesty sauces of ginger, clove, cinnamon, and pepper (Toussaint-Samat, 486). These spices would aid digestion after a heavy winter meal by heightening the effects of “hot” and “humid” properties in roasted meats. To this day, the warming spices advocated by Arnau de Villanova tend to be associated with fall and winter.

Cameline sauce, perhaps the original steak sauce, was the perfect accompaniment to roast meats. Prepared in summer and winter months alike, the sauce was so popular in some locations, such as fourteenth-century Paris, that the blend was usually readily available from the local sauce maker. There were regional varieties of Cameline sauce, too, and the “Tournais style” involved grinding together ginger, cinnamon, saffron and half a nutmeg. The spice powder was soaked in wine and stirred together with bread crumbs. The strained mixture was then boiled, with sugar added to make the winter variety of the sauce. One recipe for Cameline sauce has been adapted by Daniel Myers for the Medieval Cookery web site and is reproduced here with permission.

Cameline Sauce

3 slices white bread

3/4 cup red wine

1/4 cup red wine vinegar

1/4 tsp. cinnamon

1/4 tsp. ginger

1/8 tsp. cloves

1 tbsp. sugar

pinch saffron

1/4 tsp. saltCut bread in pieces and place in a bowl with wine and vinegar. Allow to soak, stirring occasionally, until bread turns to mush. Strain through a fine sieve into a saucepan, pressing well to get as much the liquid as possible out of the bread. Add spices and bring to a low boil, simmering until thick. Serve warm.

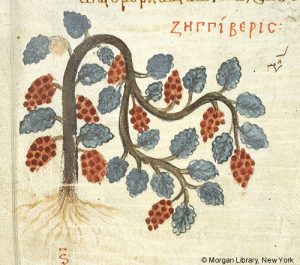

Ginger came to be highly prized during the Middle Ages, though the use of ginger can be traced back thousands of years in India and China. The potent ginger plant and rhizomes were valued for their stomach-warming and digestive properties as much as for the flavors they imparted. The first-century Greek physician Dioscorides advocated consuming a spicy Arabian plant called ζιγγίβερις (zingiberis), which was probably ginger, to “soften the intestines gently.” In Arabia, Dioscorides noted, they used only the freshest ginger plants (O’Connell 116-117).

Clove was known as one of the “lesser spices.” Though not as strong as ginger but useful for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties, clove was especially useful in dental care.

Named in English and other languages—“clou de girofle” in French—for the resemblance of the bud to nails, clove originated in the Moluccan Islands of Indonesia, the historical core of the Spice Islands. As with ginger, clove had its earliest uses in India and China in the fourth-century BCE, finding its way to Roman and Greek markets by way of port cities on the Mediterranean. By the eighth century, clove was known throughout Europe and features in several historic dishes. It was also a typical spice in pomanders, the medieval precursor to potpourri, in which fragrant ingredients were placed in a perforated box to ward off illness. The decorative use of clove-studded oranges, a seasonal pomander, is still associated with the winter months.

Hippocras, or hypocras, was a medieval spiced wine and popular cordial enjoyed especially during the winter holidays for several centuries. Hippocras was a concoction of powdered cinnamon, cassia buds, ginger, grains of paradise and nutmeg boiled with sugar and wine. Cinnamon, the essential flavor of hippocras, was a favorite spice of the medieval palate. Its mysterious origins generated many fanciful tales and even several expeditions. Perhaps most famously, the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus thought he had located the spice in America—the Indies to him— and in 1493 he reportedly brought back bits of bark from a perfumed wild cinnamon tree that was not very tasty.

Long before Columbus, the ancient Egyptians had prized cinnamon as the “… goodly fragrant woods of The Divine Land…” while medieval Arabs believed that large birds used cinnamon sticks in their nests (O’Connell, 76-77). In the first century, the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder rightly located the origin of cinnamon on the shores of the Indian Ocean. With information from some seasoned merchant, perhaps, Pliny knew that the cinnamon trade was dangerous and that a return trip to the source of the spice took almost five years. Pliny’s claims about the origin of cinnamon were eventually verified in the 1340s when the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta (1304–c. 1368) arrived at the island of Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) and discovered untouched miles of the cinnamon tree. Before its widespread appreciation as a culinary ingredient, cinnamon was prized in several ancient cultures as incense holding ritualistic importance, sometimes burned for its fragrance on a funeral pyre.

The final “proper” winter spice is pepper. With a name widely applied to many spices, including the black and white varieties, pepper was perhaps the most familiar spice of the Middle Ages. Both black pepper and white pepper are obtained from the small berries of the Piper nigrum vine.

Unripe berries are green, and ripe berries are red. Dried ripe berries yield white pepper, and despite the fantastic medieval legend propagated by Isidore of Seville (560–636) that the scorching of pepper crops blackened the berries and drove out the poisonous guard snakes, unripe pepper berries are simply plucked, gathered, cooked, and then dried to give us the most familiar variety, black pepper. The principal traders of pepper came from India where the vines thrived in tropical regions. Pepper was used in medicine to aid digestion and to treat ailments like gout and arthritis, as well as infectious diseases like the bubonic plague.

The term “peppercorn rent” derives from the practice established in early common law in England that payment of rent or tax might be made by a peppercorn, to avoid the bother of exchanging real currency. Usually no peppercorns were actually collected during these transactions, but the spice represented a hard asset, and the term is still in use today in legal parlance to describe a token amount of rent money paid in order to keep a title alive. In all seasons, spices and their increasingly globalized trade during the Middle Ages affected medieval economies, and brought social, culinary, and health benefits to Europe. To this day, the flavors and aromas of medieval markets spice up the long, cold winter months.

Sources

Paul Freedman, “Spices: How the Search for Flavors Influenced Our World,” The YaleGlobal Online Blog, March 11, 2003, http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/spices-how-search-flavors-influenced-our-world.

Daniel Myers. “Cameline Sauce.” Medieval Cookery. Last modified July 13, 2006. http://medievalcookery.com/recipes/cameline.html.

Freedman, Paul. Out of the East: Spices and Medieval Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne. A History of Food. Translated by Anthea Bell. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Leah Hyslop, “Where do Christmas spices come from?” The Telegraph.co.uk (blog), December 22, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/grow-to-eat/where-do-christmas-spices-come-from/

O’Connell, John. The Book of Spice: From Anise to Zedoary. London: Profile Books, 2015.

The governing offices of medieval church and state – such as emperor, king, pope, archbishop, abbot, mayor, and so on – were often filled by election, in accordance with public and canon law. Often, election by a voting body facilitated the peaceful transference of power, even if such decisions also considered the privileges of birth and rank, as well as the requirements of the church.

Under canon law, medieval people were guaranteed certain human rights, including welfare rights, the right of certain classes to vote, and religious liberty (Helmholz 3). Canonists supported the free exercise of these rights, as they believed them to be supported by biblical tradition. Common law, or ius commune, upheld that a right order of government on earth was based in natural law and the upholding of these God-given rights. In effect, common law and canon law were seen as linked systems, to be enforced at the highest level to promote God’s plan for the world. Voting rights were recognized under both systems, so that secular elections evolved from the system put in place by medieval canonists for choosing offices within the church (Helmholz 6).

Medieval elections took place primarily in three contexts, ecclesiastical, secular and academic, but detailed evidence about them is scarce. Voting in both ecclesiastical and secular elections could follow one of four main procedures: overseen by an external authority with no direct interest in the election; by indirect election, in which electors named a proxy to select the officials; by lot; and by ballot (Uckelman and Uckelman 3). In contrast to most modern practice, electors had a limited choice, and the outcome of an election was always subject to the judgment of their superiors. Medieval law also ruled that all of the electors had to meet at the same time in the same place, whether or not the actual voting was done in secret. This was to mimic the meeting of the apostles at Pentecost and to wait for divine guidance before voting (Helmholz 8).

For some medieval rulers, the election, crowning, and anointing of Old Testament kings proved to be an excellent model for legitimizing their rule. Biblical tradition not only provided a justification for absolute reign, it also ensured that the church remained authoritative over secular rulers. In principle, the selection of a medieval monarch was based on both elective and hereditary elements, but from the tenth century in northern and central Europe, political and social trends steered toward hereditary succession over an elective monarchy (Nelson 183). This trend is exemplified in a French manuscript titled the Avis aus Roys, or royal advice book, dating to the mid-fourteenth century and possibly made for Louis, Duc d’Anjou (1339-1385). This book highlights the benefits of adhering to hereditary royal succession, which was widely seen as a more secure and manageable transference of power than other means of selecting a ruler.

The Church’s rules for filling ecclesiastical offices presented a paradox, as they strongly favored a mix of election and hierarchy. Before the papal bull In nomine Domini of 1059, which included an election decree, the pope’s successor was most often named by the incumbent pope or by secular rulers (Larson 151). Reforms put in place over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries resulted in the creation of the first papal conclave (1276) and College of Cardinals, the familiar process for electing the pope that is still in practice today. Below the pope were elected cardinals, archbishops, bishops, and other local offices for priests and deacons. Episodes of their ritual consecration, ordination, vesting, installation, and taking orders feature prominently in the Index subject headings. Another elective office common in the Middle Ages was that of abbot or abbess of a monastery.

Among the more numerous depictions of Benedict of Montecassino delivering rule to monks is a rare episode in an Italian manuscript depicting him chosen as abbot. In this Vita Benedicti, dating to the mid-fifteenth century, a miniature depicts a group of monks presenting a letter, stamped with a dangling wax seal, to the new abbot-elect standing in the doorway of his mountain monastery.

The Index collection includes many images of election-related imagery, including depictions of medieval leadership, kingly coronations, ecclesiastical consecrations, synods, and deliberating monks. Typical subject headings include David: proclaimed King, Solomon: crowned King; Simon Thassi: chosen Leader of Machabees; Edmund of England: Scene, Coronation and Consecration; Guillaume de Machaut, Livre du Voir Dit: Scene, King addressing Court; and Louis of Toulouse: Scene, taking of Orders.

Sources

Benson, Robert L. The Bishop-Elect: A Study in Medieval Ecclesiastical Office. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Barzel, Yoram, and Edgar Kiser. “The development and decline of medieval voting institutions: A comparison of England and France.” Economic Inquiry 35, no. 2 (1997): 244-60.

Uckelman, Sara L., and Joel Uckelman. “Strategy and manipulation in medieval elections.” Accessed in http://ccc.cs uni-duesseldorf. de/COMSOC2010/papers/logiccc-uckelman. pdf (2010), 1-12.

Helmholz, Richard H. “Fundamental Human Rights in Medieval Law.” (Fulton Lectures 2001): 1-18.

Nelson, Janet L. “Medieval Queenship.” In Women in Medieval Western European Culture, edited by Linda E. Mitchell, 179-208. New York and London: Routledge, 2011.

Weiler, Björn. “8 things you (probably) didn’t know about medieval elections.” History Extra Blog. N.p., 6 May 2015.

Larson, Atria. “Popes and Canon Law.” In A Companion to the Medieval Papacy: Growth of an Ideology and Institution, edited by Atria Larson and Keith Sisson, 135-37. Leiden: Brill, 2016.