In medieval terms, March 25 was about as symbolically busy as a day could get. Already noted in the Julian calendar as the date of the vernal equinox, it is identified in the Golden Legend of the chronicler and archbishop Jacopo da Voragine as the date of an unusual number of auspicious Biblical events: Adam’s and Eve’s fall into sin; Cain’s murder of Abel; Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac; Melchisidek’s offering of bread and wine to Abraham; the martyrdom of John the Baptist; the deliverance of Saint Peter; the martyrdom of Saint James the Great; and the Crucifixion. Still more strongly associated with this date was the Annunciation, at which, according to Luke 1:26-28, the archangel Gabriel brought word to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive the son of God: “And in the sixth month, the angel Gabriel was sent from God into a city of Galilee, called Nazareth, to a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. And the angel being come in, said unto her: Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women.”

Gabriel’s announcement to Mary inaugurated the Christological narrative that governed all the feasts of the liturgical year, so it is unsurprising that this event should be highlighted in medieval calendars, where its proximity to the start of spring also led many to treat March 25 as the beginning of the new year.

The Annunciation is among the most consistently depicted subjects in medieval iconography; it is found in everything from early Christian catacombs and sculpted facades to books of hours, mosaics, and panel paintings. Its composition and details vary in accordance with its setting: the Virgin might appear on a throne, in a loggia, in a bedroom, or outdoors, and she often is shown spinning or reading. A variant of particular interest is the depiction of the Annunciation at the Spring (as it is catalogued in the Index), also known as the Annunciation at the Well. Inspired by accounts preserved in early apocryphal texts such as the Protoevangelium of James and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, this variant depicts the Virgin greeted by Gabriel as she is fetching water, the first of two successive meetings in which the angel delivers his news.

The Annunciation at the Spring emerged in late Antiquity and flourished in Byzantium and the visual traditions close to it. An early exemplar appears on a fifth-century plaque, possibly a book cover, now in Milan Cathedral Treasury. Here, a small square scene of the Annunciation initiates the narrative of Christ’s life; it depicts the Virgin Mary kneeling by a stream, pitcher in hand, as she looks back to receive the angel’s greeting. In a much later manuscript example, a twelfth-century Homilies of James Kokkinobaphos (Paris, BnF, MS gr. 1208, fol. 159v), two meetings are implied: at left, Mary dips her pitcher into a well as she turns to hear Gabriel’s message; at right, she approaches a house where she will receive the angel a second time.

A more dynamic version of the well scene appears in an early fourteenth-century mosaic in the Church of the Savior at Chora in Istanbul: composed on a pendentive below one of the structure’s domes, it positions the angel as a fluttering visitor who descends the curved surface to greet Mary as she teeters over the well below.

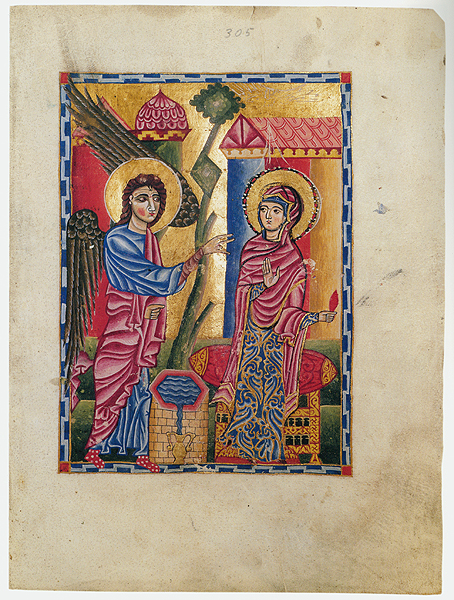

Other cultures with close ties to Byzantine traditions also adopted the Annunciation at the Spring. The scene appears among twelfth-century mosaics of the Life of the Virgin in the transept of the church of San Marco in Venice, as well as in the early fourteenth-century Armenian manuscript known as the Glazdor Gospels (Los Angeles, University of California Research Library, MS. 1, p. 305).

In the Gospels manuscript, a flattened, stylized well and pitcher offer only a vestige of the original iconography as they stand between Gabriel and the Virgin. The figures’ static postures, animated only by Gabriel’s speaking gesture and the Virgin’s raised palm, recall western Annunciation scenes, but Mary’s gilded brocade and the ogival dome at the top of the composition attest to its eastern roots.

Episodes from the life of Saint Blaise: Saint Blaise living with animals; extracting the fishbone; restoring the pig, and martyred with steel combs. Vitae Sanctorum, Anjou, 14th c. (Bib. Vat., MS lat. 8541), fol. 52v.

February 3 in the Roman Catholic calendar and February 11 in the Orthodox one mark the feast day of Saint Blaise, Bishop of Sebaste in Armenia in the early fourth century. According to his hagiography, Blaise had been trained as a physician before becoming a bishop in the early Christian church, an institution still outlawed in the Roman Empire. Seeking solitary prayer in the wilderness, he lived peacefully with the wild animals until his arrest by Roman soldiers on the orders of the Roman governor Agricola, under whom he was imprisoned, tortured, and martyred. Blaise’s best known miracles include his restoration of a pig to a woman from whom it was stolen by a wolf who returned it on the saint’s command, and the cure of a boy who was choking on a fishbone. This second miracle resulted in Blaise’s designation as the patron saint of those suffering from throat ailments, inspiring the annual tradition of the Blessing of the Throats on Saint Blaise’s Day, also known in the west as Candlemas.

Saint Blaise before Agricola, detail of a stained glass window from the Soissons region, first quarter of the 13th c (Louvre, OAR 504).

In the Index of Christian Art, Blaise is catalogued as “Blasius of Sebaste.” He is typically depicted wearing his bishop’s robe and miter and holding a crozier. In later medieval art, he often holds a wool carder’s comb, perhaps a medieval reinterpretation of the Roman steel combs with which his flesh is said to have been raked during his martyrdom. Post-medieval images sometimes depict him holding two crossed candles in an allusion to the Blessing of the Throats. His most common narrative depictions show him meditating or ministering among the wild beasts; extracting the fishbone from the choking boy; standing before Agricola; or in the act of martyrdom, sometimes accompanied by the seven pious women who, according to Eastern tradition, followed him throughout his torments, wiping up his blood.

As friends and colleagues around the world prepare to celebrate festivals of light, we at the Index wish you all a luminous holiday season and a peaceful, prosperous New Year.

Our website has had a lot of new traffic since its launch, and some users have reported difficulties getting into the database from our homepage. Please remember that if you normally access the database through an institutional subscription, you may still need to enter through your library website, using your institutional credentials. If you encounter other kinds of access problems, please use the staff contacts to let us know. We are happy to help.

Our website has had a lot of new traffic since its launch, and some users have reported difficulties getting into the database from our homepage. Please remember that if you normally access the database through an institutional subscription, you may still need to enter through your library website, using your institutional credentials. If you encounter other kinds of access problems, please use the staff contacts to let us know. We are happy to help.

The Index of Christian Art is pleased to invite applications for a one-year postdoctoral fellowship for AY 2017-2018, with the possibility of renewal contingent on satisfactory performance.

The Index of Christian Art is pleased to invite applications for a one-year postdoctoral fellowship for AY 2017-2018, with the possibility of renewal contingent on satisfactory performance.

Funded by a generous grant from the Kress Foundation, the Kress Postdoctoral Fellow will collaborate with permanent research and professional staff to develop taxonomic and research enhancements for the Index’s redesigned online application, which is set to launch in fall 2017. Salary is $60,000 plus benefits for a 12-month appointment, with a $2,500 allowance provided for scholarly travel and research. The Fellow will enjoy research privileges at Princeton Libraries as well as opportunities to participate in the scholarly life of the Index and the Department of Art & Archaeology.

The successful candidate will have a specialization in medieval art from any area or period; broad familiarity with medieval images and texts; a sound grasp of current trends in medieval studies scholarship; and a committed interest in the potential of digital resources to enrich work in art history and related fields. Strong foreign language and visual skills, the ability to work both independently and collaboratively after initial training, and a willingness to learn new technologies are highly desirable; previous experience in digital humanities, teaching, and/or library work is advantageous. Applicants must have completed all requirements for the PhD, including dissertation defense, before the start of the fellowship. Preference will be given to those whose subject expertise complements that of current Index staff.

Applications will be reviewed beginning January 15 and will continue until the position is filled. Applicants must apply on line at https://jobs.princeton.edu/applicants/jsp/shared/Welcome_css.jsp, submitting a C.V., a cover letter, a research statement, and the names and contact information of three references. The position is subject to the University’s background check policy.

Princeton University is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer, and all qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to age, race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, national origin, disability status, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law.

The Index will be represented at two events at the Medieval Congress at Kalamazoo this year. First is a joint reception with the Research Group on Manuscript Evidence at 5:15 pm on Friday, May 13, in Bernhard 208. Second will be two sessions, titled “Pardon Our Dust: Reassessing Iconography at the Index of Christian Art,” organized and chaired by Index researchers Catherine Fernandez and Henry Schilb, on Sunday from 8:30 to noon in 1145 Schneider Hall. We hope to see many friends there!

Heartfelt thanks to the over 150 people who took our online survey this past month. Your thoughtful, detailed responses will be central to our plans for the coming year. They confirmed many concerns already on the mind of Index staff, especially concerning the difficulties of navigating our current database. They resolved a few hot office debates over how researchers approach the system (Team “Keyword Search” routed Team “Browse List,” 93-7, while “Search by Subject” ran away with “Initial Search Field,” earning 87% of responses). They also offered high marks for the accuracy of our data and the quality of our programs and publications. Most appreciated of all, however, were your concrete, insightful suggestions about how the new database could be designed so as to perform most effectively for an evolving scholarly community.

Heartfelt thanks to the over 150 people who took our online survey this past month. Your thoughtful, detailed responses will be central to our plans for the coming year. They confirmed many concerns already on the mind of Index staff, especially concerning the difficulties of navigating our current database. They resolved a few hot office debates over how researchers approach the system (Team “Keyword Search” routed Team “Browse List,” 93-7, while “Search by Subject” ran away with “Initial Search Field,” earning 87% of responses). They also offered high marks for the accuracy of our data and the quality of our programs and publications. Most appreciated of all, however, were your concrete, insightful suggestions about how the new database could be designed so as to perform most effectively for an evolving scholarly community.

Three issues emerged repeatedly in the survey results. First was navigation: many researchers reported difficulty using the online database because of outdated or unwieldy design, unfamiliar terminology, and a lack of research guidelines. Close behind this was cost: past subscription fees for the Index have been high enough to make access difficult for smaller institutions and individuals. Finally, many researchers expressed concern about access to and quality of images: not only did past policies at the Index restrict many images from view by remote users, but the quality of our older images (some nearly a century old) can be quite low.

We hear you, and we are happy to say that most of these issues should be mitigated as we move to a new database design over the next two years. We are currently engaged in selecting a vendor to create the new system, which will be more intuitive, researcher-oriented, and image-centered than the original 25-year-old design. We also expect it to be more efficient, allowing us to migrate existing data and integrate new material, including improved images, with greater speed and effectiveness, while nationally changing practices surrounding copyright and fair use will allow us to make more of those images available universally. Finally, once a vendor is selected and the database is in design, we will address the question of subscription costs with our advisory committee, with the goal of offering more affordable access to the database for both institutions and individuals, including independent scholars and students.

We look forward to sharing news of all the changes to come at the Index as we approach our 100th year, and as always, we look forward to hearing from you when our resources or research staff can be of help to your work.

As you may know, the Index of Christian Art is in the midst of a major and long-awaited redesign aimed at making our online database more flexible, accessible, and user-friendly. Please help us by taking a very brief (5-10 minutes) survey about your use of the current database. Your responses will help refine the new design with our researchers’ needs in mind. You can access the link here.

All responses will remain anonymous, and all will be valuable in helping us to design a new database that will better serve you and all researchers whose work concerns the history and signification of images in the Middle Ages.

Thank you very much for your support of our work.

“Plus Ça Change…? The Lives and Afterlives of Medieval Iconography” takes place on April 29 at the Index of Christian Art. Presentations include:

“Rejection, Distortion and Destruction at Santa Maria in Trastevere.”

Dale Kinney, Professor of History of Art Emeritus, Bryn Mawr College

“The Archaeology of Carolingian Memory at Saint-Sernin of Toulouse.”

Catherine Fernandez, Research Scholar, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

“How Reliquaries Resist Iconographic Classification But Still Have Meaning”

Cynthia Hahn, Professor, Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center

“Signatures and Traces in the Art of al-Andalus.”

D. Fairchild Ruggles, Professor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

“Debating the Transfiguration In Fourteenth-Century Byzantium; or Why There Is No Hesychastic Art.”

Charles Barber, Professor, Princeton University

“The Frailty of Eyes.”

Kirk Ambrose, Professor and Chair, University of Colorado, Boulder

“Figuring Absence: Iconography and the Failure of Representation.”

Elina Gertsman, Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University

“The Work of Gothic Sculpture in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”

Jacqueline Jung, Associate Professor, Yale University

Generously co-sponsored by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, Princeton Medieval Studies, Princeton Art & Archaeology, and the Steward Fund in the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University. We look forward to seeing you!

Shepherd at the Nativity. Fourth century sarcophagus. Arles, Musée de l’Arles et de la Provence Antique, FAN.92.00.2517. Index system number 000107697.

Of all the medieval images associated with the Christmas story, surely most familiar is that of the Nativity, which depicts the Christ child in the lowly stable of his birth, almost always attended by the Virgin Mary, her husband Joseph, and the ubiquitous ox and ass. Medieval nativity scenes often included other onlookers as well, from the shepherds and magi to whom angels announced Jesus’ birth to the midwives who, in some accounts, assisted at it. Of all these figures, few have a longer or more engaging history than the shepherds, with whose homespun character and simple faith many ordinary medieval Christians could identify.

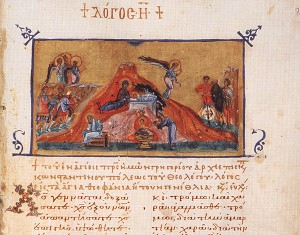

Shepherds and Magi at the Nativity. Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen, 11th century. Jerusalem: Greek Patriarchal Library, MS Taphou 14, fol. 80r. Index system number 150818

The shepherds themselves have biblical origins: Luke 2:8-20 describes them receiving news of Christ’s birth from a host of angels, then rushing to the stable to see the child for themselves. The scene of the angelic annunciation to the shepherds is sometimes presented adjacent to or in the background of the Nativity, and in the very late Middle Ages, under the influence of Franciscan piety, it was also depicted as an independent scene. However, from the beginnings of Christian art, the shepherds were also frequent onlookers at the Nativity itself. By the fourth century, Roman and Gallic sarcophagi had begun to include one or two shepherds standing beside the manger, often raising a hand in recognition of Jesus’ divinity; middle Byzantine mosaics often cast the shepherds as a trio to balance the three magi who also attended the child. Such pairings were encouraged by medieval texts that presented the shepherds as symbolizing the Jewish tradition from which Christianity had sprung and the magi as representing those pagans who converted to the faith. Alternatively, the magi and shepherds were sometimes presented as demonstrating Christ’s recognition by all walks of life, a universalistic message sometimes developed further in the portrayal of both groups as men of varying ages and even ethnicities.

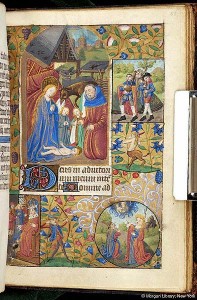

Music-making shepherds on the margin of the Nativity, ca. 1470. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS m.32 fol. 51r, Index system number 000175635

Late medieval pietistic trends, which promoted the idea that the poorest of men had been the first to receive news of Christ’s birth as confirmation of the value of humility and simplicity, encouraged fourteenth- and fifteenth-century artists to elaborate their images of the shepherds. They often are shown as rough-hewn peasant types—sometimes even including a shepherdess—who offer the child simple, heartfelt gifts, such as a lamb, a flute, flowers or, more unusually, a basket of eggs. The appeal of these humane, familiar figures still resonates in many a Christmas sermon as well as Christmas carols, from the traditional Austrian “Shepherd’s Carol” to the 1941 pop hit “The Little Drummer Boy.”

Shepherds are noted in over 650 records of the Nativity in the online database of the Index of Christian Art; many more can be found in the card files. Media include sculpture, gold glass, manuscripts, enamel, mosaic, fresco, and painting. We wish all our friends who celebrate Christmas a joyous and peaceful holiday.