As editorial staff at the Index continue cataloging our physical backfiles, which contain over 200,000 photographs of works of art in sixteen media categories, we are happy to announce that at last, all our print records of gold glass objects have been fully digitized in the Index database! In gold glass, an image in gold leaf is fused between layers of glass. Gold glass was a favored art form in Hellenistic Greece and during the Roman period, often decorating the bases of feasting vessels, such as bowls, cups, and plates, with hidden pictures that would slowly be revealed during the consumption of food and wine. The newly digitized “Gold Glass” backfiles document over 650 objects from about 60 locations. Most examples are identified as vessels, medallions, or plaques (Fig. 1).

The glittering portraits on these glass objects, now mostly fragmentary, are usually bust length and often show whole families. These are classified under the Index subject “Family Group,” while the subject “Married Pair” is used for images depicting a bride and groom, sometimes crowned by Christ. Gold glass objects are frequently associated with marriage celebrations, and several pieces retain the names of the men and women depicted with inscriptions of good wishes. Frequently, this inscription is the Latin drinking toast “PIE ZESES” (“Drink to live,”), either in full or abbreviated, although a fourth-century gold glass fragment from Rome, now in the British Museum, bears the more sentimental words “DVLCIS ANIMA VIVAS” (“Sweet soul, may you live [long]”) around the heads of the newlyweds (Fig. 2).

Several gold glass objects contain other paired figures, especially Peter and Paul the Apostles, as the patron saints of Rome, and Adam and Eve, commonly represented in the Fall of Man scene. Old Testament narratives and figures, such as Moses, Abraham, Daniel, and Jonah were popular, and Christian miracles were also frequently depicted on vessels. The Index database contains just over fifty miracle scenes executed in the gold glass medium, including the Raising of Lazarus, the Miracle of Loaves, and the Wedding at Cana, suggesting that healing themes held some favor among patrons. The objects may also have served a commemorative function.

Some surviving gold glass objects contain Jewish iconographic motifs, including the Temple implements, such as the menorah, shofar, etrog, and Torah Ark. These implements can be found in the Index database by browsing the Subject list, or by searching for “gold glass” as a term and filtering by the Style/Culture “Jewish.” Mythological figures and narratives from the classical world were also favored subjects to depict on gold glass vessels. The Herculean labors, sea-nymphs, and cupids can be identified on some fragments. Other well-represented motifs in the medium include the “Good Shepherd,” which has iconographic connections to the ancient Greek ram-bearing cult figure Kriophoros. There remains much to discover and assess about images in gold glass and their meanings, production, and patronage throughout the late antique, Roman, and Byzantine periods, making the Index an essential study tool. Now, with increased access, more researchers can learn how this rather fragile art form documents fashion, commerce, rituals, and historical names and epigraphs from ancient daily life (Fig. 3).

The Index gold glass backfiles received significant attention by Ryan Gerber, our 2019 summer intern from the Rutgers School of Communication, who is now a Marquand Art Library Collections Specialist. Gerber inventoried the collection and wrote about his impressions in a blog post called “A Face in Gold Glass.” After Henry D. Schilb, Index Art History Specialist in Byzantine Art, finished adding the collection with the help of Gerber’s inventory, he noted that many gold glass objects recorded in major nineteenth century catalogs did not survive into the modern era. Thus, the publications that earlier Index catalogers used in their research may have contained the last known record of an object’s existence. Schilb said, “it was surprising to learn that many of the gold glass objects entered into the Index files have been lost to time, and at least one of them was apparently reduced to dust in the collection where it was last recorded. Not surprisingly, we have also simply lost track of several examples that were originally cataloged by Indexers before the Second World War.” With too little information to go on, the Index cataloger can sometimes upload only a drawing from the catalog and record only a “Last Known Location” for objects presumed lost to history. When we just don’t know where something is, we indicate this in the database by giving “Unknown” as the current location with a “Last Known Location” to identify the place where an item was last known to exist. This can apply to items that we know to have been destroyed, but it also applies frequently to items that are either simply lost or are now in unidentified, private collections. Although the Index can sometimes discover an object’s true current location, that bit of data can sometimes elude us, so we always welcome intelligence from anyone who might have a good lead!

It is a great achievement when we can complete an entire category in the backfiles with newly researched information, including updated location names, fuller iconographic descriptions, and new or updated terms from Index vocabularies to expand the findability of work of art records. We ought to be clear, however, that we do not claim to have recorded every known example of any medium or type of object. That must remain an ongoing project. Nevertheless, the whole Index team is thrilled to make the gold glass corpus of the original Index card catalog fully available in the database. If you want to see for yourself, you can browse “gold glass” records by Medium more fully here: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/list/ListMediums.action. You can also reach out to us with any inquiry here: https://ima.princeton.edu/research-inquiries/. Please let us know how the Index can improve the records we have, or find out how the Index can serve your own research needs.

Cheers!

Further Resources

Garrucci, Raffaele. Vetri ornati di figure in oro: Trovati nei cimiteri dei cristiani primitivi di roma. Rome: Tipografia Salviucci, 1858.

Deville, Achille. Histoire de l’art de la verrerie dans l’antiquité. Paris: Morel, 1871.

Vopel, Hermann. Die Altchristlichen Goldgläser: Ein Beitrag zur altchristlichen Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte. Freiburg im Breisgau: J. C. B. Mohr, 1899.

Morey, Charles Rufus. The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library: With Additional Catalogues of Other Gold-Glass Collections, ed. Guy Ferrari. Vatican City: Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1959.

Meek, Andrew. New Light on Old Glass: Recent Research on Byzantine Mosaics and Glass. London: British Museum Press, 2013.

Howells, Daniel Thomas. A Catalogue of the Late Antique Gold Glass in the British Museum. London, British Museum Press, 2015.

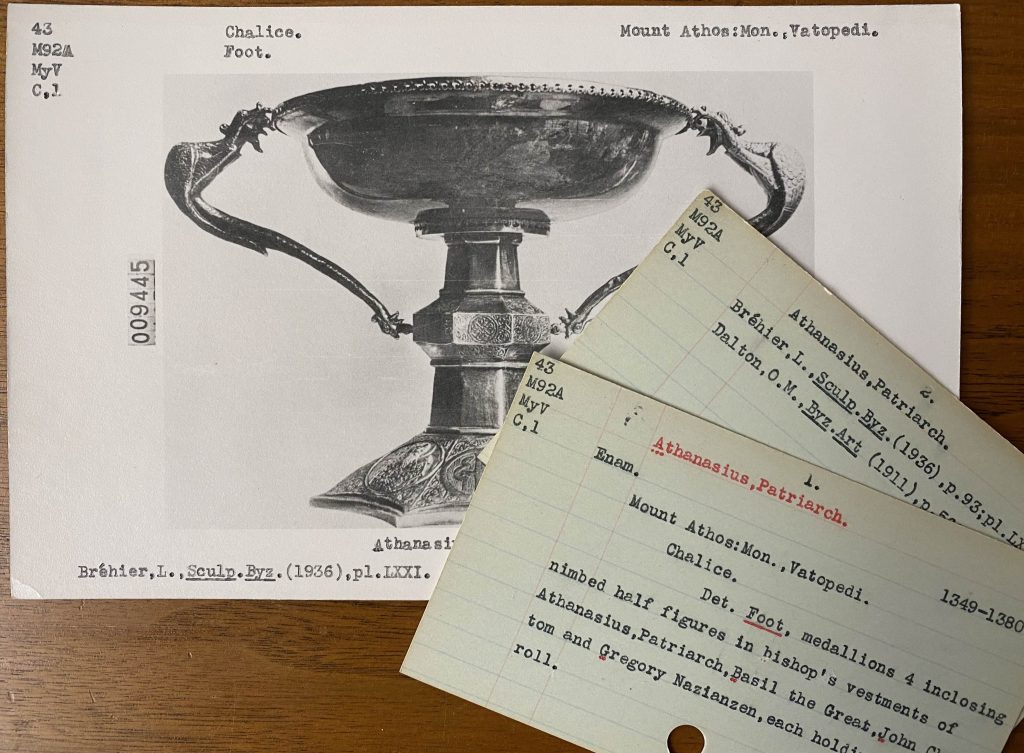

We are excited to announce a short-term graduate opportunity at the Index of Medieval Art! This is a two to three-month remote, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works of art on Mount Athos into the Index database. The position would require the student to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. They will be trained in Index norms in cataloging works of art, describing the iconography, transcribing inscriptions, and adding bibliographic citations.

The position is part of a new multi-year project, Connecting Histories: The Princeton and Mount Athos Legacy, that aims to create an international team of faculty, staff, and students that will explore and bring awareness to the rich, complex, and remarkable historical and cultural heritage of Mount Athos, and its connection to Princeton. This opportunity offers a stipend of $2,500 and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.

The deadline for applications is December 1, 2023. For more details about eligibility criteria and the application process, please visit the “Announcements” page on the Connecting Histories website.

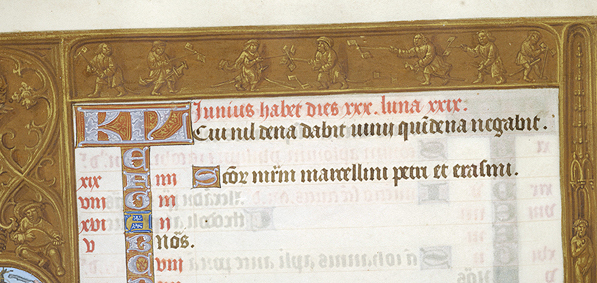

It’s May again, the month that marked the traditional beginning of summer in the Middle Ages. Much as it still is today, this seasonal turn was celebrated with festivals that set aside the toil of spring in favor of games and leisure. In medieval iconography, this time of the year is also captured in a variety of courtship scenes belonging to a genre known as “courtly love.” Such scenes sometimes represented the month of May with depictions of couples playing a game of chess or setting out on horseback for the sport of falconry and hunting, as well as holding merry engagements around fountains or flowing springs. The typical zodiac sign associated with the month of May was Gemini, usually represented by a pair of either twins or lovers, which epitomized the idea of two for this time of year: a double, a match, and a mirror image.

The iconography of mirror and fountains is similar in its ability to emanate personal reflections of a viewer, which made them desirable themes to utilize in courtly imagery. While the idea of gazing at your “twin,” perhaps framed in a window or seated across a chessboard, was celebrated in the Middle Ages, looking at your own reflection for too long, or for the wrong reasons, was frowned upon. A classic warning appears in the tale adapted from Ovid’s Metamorphoses of the mythological Greek hunter Narcissus, who so loved his own reflection that he became fixated on it for life, rejecting all offers of love.

The Narcissus theme is represented in a late fifteenth century miniature in an English manuscript of the Confessio Amantis (“Confessions of a Lover”) by John Gower (d. 1408). The artist depicts a kingly Narcissus wearing a crown, a vair-lined garment, and a jeweled girdle while staring at his own reflection in a fountain (Fig. 1). Narcissus stands in a fenced enclosure surrounded by a unicorn, a collared dog, and a stag. The presence of the stag evokes an Aesopian fable with a similar message, usually called the “Stag and its Reflection” (or the “Proud Stag”), in which a stag admires his antlers in a pool for too long and is caught by the hunter. Like its captive animal companions, the stag echoes Narcissus’s enmeshment in his self-image and ties him to the fountain.

In the popular medieval romance known as the Roman de la Rose, by Guillaume de Lorris (fl. ca. 1230), the “Lover” (Amans) encounters the Fountain of Narcissus and is similarly drawn to look at the reflection of his face in the water (Fig. 2). Like Narcissus, the Lover in the Roman de la Rose is taken with his own beauty in the pool and leans over to admire it; but unlike that of Narcissus, the pool is also the “Fountain of Love,” which destined all who looked in to fall in love. Thus, the Lover’s self-reflection is deeper and more altruistic than his external features, allowing him to overcome the curse of vanity and experience an ideal transformation.

Among the most interesting imagery related to mirrors, fountains, and love is that on Gothic mirror cases, also called valves de miroir. Over seventy examples currently exist in the Index of Medieval Art database, and you can find them by browsing for “Mirror Case” under Work of Art Type. Such mirror cases would twist open to reveal a polished metal disk for personal reflection, while imagery on the closed case told an allegorical story linked with chivalric lore. Mirrors have been part of society since antiquity when they were first made of highly polished stones. The mirror is an essential tool in the iconography of the Toilet of Venus, and it also became both a virtuous attribute for the self-aware personification of Prudence and a sign of vice for that of Vanity. Yet the images carved on Gothic ivory mirror cases rarely warn about the dangers of selfish looking. Instead, they often present scenes of youthful love. On a mirror case in the Walters Art Museum, within the arched portcullis of a castle, a man cups the chin of a woman in a gesture called “chin-chucking” (Fig. 3).

On the Walters ivory mirror back, other young people engage in friendly activities while a group of disabled or elderly persons parade toward the waters of the allegorical “Fountain of Youth” seeking an immortalizing dip. A similar procession of four pairs of men and women meeting at a central two-tiered fountain issuing streams of water appears on a double-sided ivory comb in the Victoria & Albert Museum, made ca. 1400 (Fig. 4). Here, the couples do not gaze into the fountain, nor do they bathe in its restorative waters, but the fountain separates the groups into symmetrical pairs, suggesting an impending connection. The glossy surfaces of mirrors and fountains, with a myriad of possible reflections—of a person’s vanity or deep self-knowing, the promise and capture of love, or the hope of love as a soothing, restorative balm—made these water features the appropriate gathering places for courtly lovers.

The month of May can resemble December for those of us on the academic calendar. The buzz of the semester diminishes to a low hum; there are fewer events, fewer emails to answer, and fewer faces around campus as people take time away from university life. Some might take a break from their work to review their activities and reconnect to individual goals and missions. These yearly transitions can also be times of reflection. Wherever this summer takes you, for work or on trips to faraway lands, we wish you good health and safe travels!

Select Subjects of “Love” Interest in the Index of Medieval Art

The following iconographic headings can be accessed in the Index of Medieval Art Subject List:

Married Pair —The iconographic depiction of a husband and wife together, identified or not.

Marriage—A scene of matrimony or wedlock celebrating the union of two people as they become spouses.

Castle of Love—The “Castle of Love” allegory is associated with the iconography of chivalry and courtly love and is often represented on fourteenth-century ivory mirror cases and caskets. Also known as the Siege (or Attack) on the Castle of Love, it typically includes the God of Love (Eros or Cupid) holding a bow and arrow and positioned on the top of a castle while women, couples, and lovers defend the tower, sometimes by tossing roses on battling equestrian knights below.

Courting—Index subject incorporating various scenes of courtly love, including crowning lovers, or couples chin-chucking, also used in combination with scenes of falconry, hunting, or chess.

Couple—The term to describe a pair of people, usually a man and woman depicted as lovers.

Falconry—Also known as “Hawking.” The sport of hunting with predatory birds is especially associated with the iconography of the Labors of the Month for April and May and scenes of courtship with figures and couples holding the birds of prey.

Fountain of Love—An allegorical fountain for courting lovers as described by the fourteenth-century French composer Guillaume de Machaut.

Fountain of Youth—An allegorical fountain or spring which, according to legend, had the power to restore youth to anyone who bathes in its waters.

Labors of the Month, May—The occupation for the month for May, usually represented by an outdoor scene of courting or the sports of hunting and falconry, often by equestrian couples. Variants of this scene include the courting lovers walking in a landscape, sometimes holding hawks, falcons, flowers, or branches, or sometimes depicted in a scene of merriment involving musicians.

Mirror—A polished surface, often held by a handle or decorative frame, and reflecting a clear image of what it is pointed at. Attribute of the vice personification of Vanity. Sometimes held by the goddess Venus.

Sexual Activity—The subject for figures engaging in any explicitly sexual activity. Often suggested by two people lying down in close proximity to each other, possibly nude, possibly embracing each other, and sometimes in a bed.

Further Reading

Camille, Michael. The Medieval Art of Love: Objects and Subjects of Desire. New York: Abrams, 1998.

Hult, David F. “The Allegorical Fountain: Narcissus in the ‘Roman de la Rose.’” Romanic Review, 72, no. 2 (1981): 125–50.

Lewis, C. S. The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Peklar, Barbara. “The Imaginary Self-Portrait in the Poem Roman de la Rose.” Ars & Humanitas 11, no. 1 (2017): 90–105.

Other Resources

The British Museum. “A ‘Greatest Hits’ of medieval myths on a casket | Gothic Ivories 1 | Curator’s Corner S7 Ep4.” YouTube Video, 11:57. June 23, 2022. https://youtu.be/IA0sWopdLxs.

Gothic Ivories Project at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Accessed February 14, 2023. http://www.gothicivories.courtauld.ac.uk/.

The Index staff is pleased to announce the relaunch of the Index’s digital image collections, which have recently undergone a massive upgrade. The updated platform hosts ten collections of images generously donated to the Index and made freely accessible to the public through the Index website. These unique documentary resources include more than 50,000 images of medieval art and architecture and reflect the varied interests and travels of their twentieth-century photographers. They represent a range of subjects, techniques, and media, including English medieval embroidery, medieval and Byzantine manuscripts, European choir stall sculpture and stained glass, and Gothic and Romanesque architecture.

Although the images in these collections have not been cataloged with the same level of detail as those in the iconographic database, every effort has been made to assign them basic information regarding location, date, and in many cases, iconographic subjects. The latter can be found in browse lists that include a variety of iconographic topics, including saints and martyrs, animals, zodiac, occupations, and secular and religious scenes, all updated to follow the current subject standards of the main Index database. Browsing these subject lists reveals much about each collection. For instance, the subject list for the “Opus Anglicanum” database—an image collection of medieval English needlework on ecclesiastical and secular textiles—includes numerous saints especially venerated in England, with multiple scenes for Margaret of Antioch, Nicholas of Myra, and Thomas Becket.

Browsing the subject list of another collection, the Elaine C. Block database of misericords, reveals the wide variety of drôleries that decorated the wooden under-seat structures: fantastic creatures, battling animals, and figures playing in sports and games, engaged in occupations, or enacting proverbial lessons. John Plummer’s database of medieval manuscripts includes large numbers of biblical and apocalyptic images, including scenes with Christ, David, and the Virgin Mary, and other popular saints found in late medieval prayer books. The subjects in Plummer’s collection closely resemble those found in Jane Hayward’s collection, perhaps reflecting the shared interests of two scholars were curators at major collections in New York City during the second half of the twentieth century.

The Gabriel Millet collection comprises the study and teaching images of that scholar, an important archaeologist and historian of the early twentieth century who specialized in Byzantine art. Subjects represented here include multiple biblical figures and scenes, but also Byzantine generals and emperors and several text subjects, such as the Chronicle of Manasses and the biblical psalms by number.

The Gertrude and Robert Metcalf Collection of Stained Glass is a documentary treasure for the study of Gothic stained glass. The Metcalfs, who were both stained glass artists and experienced photographers, took more than 11,000 images of stained glass from European monuments, covering sites in Austria, England, France, Germany, and Switzerland. Their images of stained glass windows are a fascinating record of a fragile artistic medium, captured during fragile times. Their travels coincided with the dawn of World War II in Europe over the years 1937 and 1939, and they produced a body of documentary evidence that became critical to postwar restoration efforts. A look at the Metcalf subject list reveals many of the expected themes in medieval iconography, but also significant iconographic cycles for several French bishops, such as Austremonius and Bonitus of Clermont, Germanus of Auxerre, and Martialis of Limoges.

Geographically, the collections cover country and city locations in four continents—Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America—from obscure sites to famous ones, and they include many types of repositories, from in-situ locations to museums, libraries, and private collections. To better accommodate browsing by region, locations in all the collections have been formatted to begin with the country. Each collection is introduced with general information about its history, scope, and image use policies. It has been satisfying to edit and release these collections—now with more consistent information and a more secure digital platform—knowing that they are now more useful to scholars. Your feedback on the collections is welcome via this form.

Continuing a series of blog posts introducing the new features of our online database.

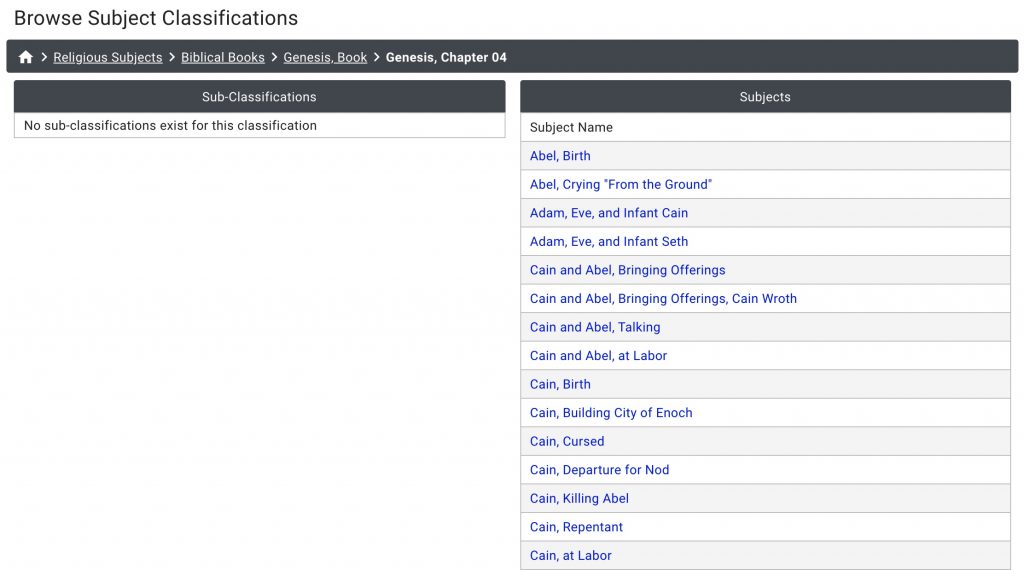

The Index of Medieval Art database catalogs more than 26,000 subjects. For a long time, you could explore this vast taxonomy only by browsing the subject headings in alphabetical order. To make the data more accessible, the Index has developed a Subject Classification browse tool, which allows researchers to discover Index holdings by browsing through various categories of our hierarchical classification of subjects.

In this network, subjects are grouped under five top-level headings:

By browsing the contents of these categories, researchers can learn more about Index subjects as grouped by theme. Researchers interested in the “History” category, for example, will encounter individual subjects, such as the names of historical figures and their associated scenes within a medieval society, grouped under classifications such as “Heraldry,” “Donors,” “Founders,” and “Nobility.” Other groups in this category include “Those Who Pray” (including representations of religious clergy, pilgrims, missionaries, hermits and heretics), “Those Who Fight” (with admirals, generals, officers, etc.), “Those Who Rule” (with emperors, empresses, doges, despots, prefects, etc.), and “Those Who Work” (including medieval occupations by type, such as philosophers, physicians, and scholars).

The category “Religious Subjects” contains diverse subject matter, mainly figures and scenes, but also objects and rituals, not only for the three Abrahamic faiths of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, but also for several other ancient religions, such as Greek, Roman, and Egyptian mythology. The unsurprisingly large iconographic groups for the Life of Christ and the Life of the Virgin Mary, which include the names of individual biblical figures and saints as well as biblical scenes, live in this part of the network and represent a wealth of catalogued examples in the database. Under “Religious Subjects,” biblical scenes are also grouped by their numbered books and chapters. These classifications allow researchers who are broadly interested in the iconography from a biblical source, such as the Genesis narrative, to access “Biblical Books” then “01. Genesis, Book,” and then go to a specific category. For example, the category “Genesis, Chapter 04” lists subjects of related figures and scenes appearing in Genesis 4, such as those for Adam, Eve, Cain, and Abel. Each biblical book with associated iconography in the database can be browsed for associated subject headings, including the subjects for the Psalms (following the Vulgate numbering 1–150). Researchers pursuing iconography related to texts other than the Bible will want to browse the “Literature and Legends” category, accessed from “Non-Biblical Texts” under “Society and Culture,” which contains subjects relating to the Trojan War, the Aeneid, the Legend of the Argonauts, and Arthurian Legend, among others.

The “Society and Culture” category contains a wide variety of subject terms for representations of medieval daily life. Here you will find types of work, garments, objects, utensils, musical instruments, and furniture that the Index has identified in medieval works of art, plus an array of occupational activities, such as travel, sports, eating and feasting, and hunting scenes. Exploring the category “Sports and Games” might yield unexpected names of pastimes enjoyed in the Middle Ages. Subject terms for games such as “Chess” or “Draughts” are familiar, but others, such as “Whirligig,” might invite a deeper look.

The “Nature” category is a treasure trove for anyone interested in medieval representations of animals, plants, geography, and astronomy. Here you will also find fascinating mythological creatures and hybrid figures alongside visualizations of the seasons, climate, and natural disasters. The “Symbol, Concept, and Ornament” category contains subjects for the more abstract topics in the Index collection. It currently organizes representations of allegories by name and personifications by type, including human characters for the arts, nature, places, time, virtues and vices. This category also includes maps and diagrams, monograms of individual figures, and various kinds of figured, floreate, and foliate ornament.

More a network than a strict hierarchy, the Subject Classification tool is designed to be flexible in its groupings, because the Index of Medieval Art recognizes that medieval iconography does not always fit into predetermined categories or may fit into many categories. For example, Charlemagne, the Carolingian King of the Franks and later Emperor of the Romans was also revered as a saint in some locations, so he appears in multiple parts of the network, including:

When clicking on the lowest-level subject heading, in this case “Charlemagne,” a new page will appear displaying this subject heading’s authority record. The authority record provides an array of useful information, including a Note field at the top offering a definition of the subject, or biographical details, followed by expandable fields containing select bibliographic citations, External References (cross-references to other authorities) and See Froms (alternative names and spellings of the subject). At the bottom of each subject authority is the Associated Works of Art field, an expandable field containing links to all the medieval works of art that feature this iconography.

The authority record’s Subject Classifications field presents the lowest network category, or categories, to which the subject belongs. In the example of “Charlemagne,” it is the name of the individual figure. In other instances, the Subject Classifications for a particular subject might appear on the authority as a broader grouping term. For example, the subject authority for “Drinking Horn” will use the subject classification “Utensils and Objects D–H,” and the subject for “Robin” will use the classification “Birds H–Z.” As noted in the example for biblical books, the subject classifications can also contain names of textual sources, including legends and other narratives.

The evolution of the Subject Classification tool is ongoing, allowing for continuous discovery by both those who use it and those who are building it. As branches of the network spread, new and surprising associations emerge, revealing the richness of the Index’s subject taxonomy. We hope you will enjoy browsing the iconographic headings with this new database tool, which is openly accessible to anyone who visits the browse page of the Index of Medieval Art database.

The Index of Medieval Art Subject Classifications comprises a browsable network that organizes and associates subject terms from our vast taxonomy of medieval iconography. These classifications are descriptive and not prescriptive of medieval works of art cataloged into the Index collection. What follows is an outline of the top three levels of classifications to give Index researchers the broadest overview of subject content.

Heraldry

Heraldic Symbols

Heraldry of Miscellaneous Figures and Families

Identified Heraldry A–Z

Legendary Heraldry A–Z

Historical Figures

Donors A–Z

Founders A–Z

Nobility

Those Who Fight

Those Who Pray

Those Who Rule

Those Who Work

Animals

Birds A–Z

Hunting and Other Scenes

Insects and Invertebrates

Mammals A–Z

Marine Creatures

Reptiles and Amphibians

Astronomy and Astrology

Constellations

Planets and Other Celestial Objects

Sun and Moon

Zodiac

Geography and Geology

Landscape

Minerals and Gems

Mountains

Natural Elements

Rivers

Sea and Ocean

Weather and Natural Disasters

Mythological Creatures and Hybrids

Animal Hybrids

Hybrid Figures

Mythological and Religious Creatures

Plants

Plants and Flowers A–Z

Trees and Their Fruits A–Z

Time

Months

Seasons

Times of the Day

Biblical Books

Genesis, Book–Maccabees, Book

Matthew, Book–Apocalypse, Book

Christianity

Angels and Devils

Christian Legends

Christian Objects and Rituals

Christian Religious Orders and Offices

Death and Afterlife

Divine Manifestations

Images and Attributes of Christ

Life of Christ

Life of the Virgin Mary

New Testament Apocrypha

New Testament Figures

Old Testament Apocrypha

Old Testament Figures

Saints

Types of the Virgin Mary

Greek and Roman Mythology

Mythological Figures A–Z

Mythological Narratives

Islam

Muslim Objects and Rituals

The Life of Muhammad

Judaism

Jewish Biblical Figures and Narratives

Jewish Objects and Rituals

Other Ancient Religions

Egyptian Deities

Gnosticism

Mithraism

Zoroastrianism

Architecture

Cities A–Z

Identified Buildings A–Z

Models of Buildings and Cities

Unidentified Buildings and Structures A–Z

Drollery

Drolleries and Grotesques

Figure Types

Ethnic, National, Religious, and Social Types

Figure Types A–Z

Human Hybrids

Hybrid Figures

Imaginary Figures

Labors of the Month

Months

Furniture

Bed, Bench, Lectern, Throne, etc.

Garments and Accessories

Hats, Headgear, Jewelry, etc.

Human Activities

Eating and Feasting

Hunting and Other Scenes

Medicine and Medical Practices

Occupational A–Z

Social Activities

Sports and Games

Travel and Commerce

Non-Biblical Texts

Literature and Legends

Objects and Rituals

Christian Objects and Rituals

Jewish Objects and Rituals

Muslim Objects and Rituals

Utensils and Objects

Musical Instruments A–Z

Utensils and Objects A–Z

Warfare

Arms and Armor

Military Figures

Military Scenes

Allegories and Personifications

Allegories

Personifications of Arts

Personification of Christological, Symbolic, and Literary Concepts A–Z

Personifications of Nature

Personifications of Places

Personifications of Time

Personifications of Vices

Personifications of Virtues

Maps and Diagrams

Alchemical, Alphabetical, Geometric, Astronomical Diagrams, etc. and Maps

Monogram

Monograms of Individual Figures A–Z and Symbols

Ornament

Animal, Figured, Floreate, and Foliate Ornament

By Jove! This year a special planetary alignment will occur on December 21st, also the Winter Solstice, when earth’s northern pole is at its greatest tilt away from the Sun. During this “Longest Night,” the planets Saturn and Jupiter will be within a tenth of a degree to one another, appearing to form a single “star.”

While an alignment of Saturn and Jupiter happens about every 20 years, when it happens in 2020 it will be one of the closest alignments of these two planets for over 800 years, and by some accounts since the year 1226.[1] The 1226 Saturn-Jupiter conjunction coincided with several historical milestones. In France, the reign of Louis IX, the only French king to be canonized by the Catholic Church, began following the death of his father Louis VIII. In Norway, the cleric Brother Robert translated the popular chivalric romance of Tristan and Iseult into Old Norse at the request of King Haakon IV. In the Kingdom of Georgia, the Sultan Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, last ruler of the Khwarezmian Empire, captured Tbilisi in the Battle of Garni. The mendicant friar, preacher, and later saint Francis of Assisi died on October 3rd. And according to Canadian astronomer and historian Vibert Douglas, the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan abruptly ended his military campaign in China, possibly owing to the phenomenon of five separate planetary conjunctions over the years 1226 and 1227.[2]

In the Middle Ages, the seven “planets”—Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Mercury, and the sun and moon—were important celestial bodies in the heavenly realm. Each was thought to have a distinctive personality, an idea still reflected in Gustav Holst’s orchestral suite The Planets, composed between 1914 and 1916. Holst calls Jupiter “The Bringer of Jollity” and Saturn—colloquially also known as “Father Time”—“The Bringer of Old Age.” These names doubtless influenced the artistic expression in the series of dance performances for Holst’s Planets by the Princeton University Ballet in 2018 linked above.

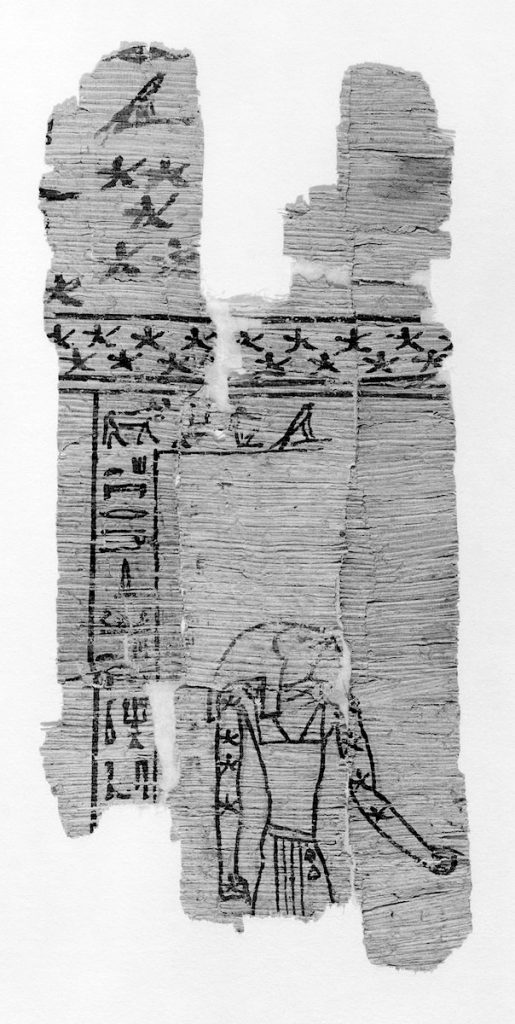

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, was initially named after the ancient Roman god of thunder, and its planetary neighbor Saturn, the god of agriculture and harvest, was also Jupiter’s father. In Greek mythology they are Zeus and Cronus and were sometimes represented by medieval artists as luminous pointed stars, or solid spheres in concentric circles of earth-centered astronomical diagrams, as in this later copy of a Byzantine geocentric model of the cosmos (Fig. 1).

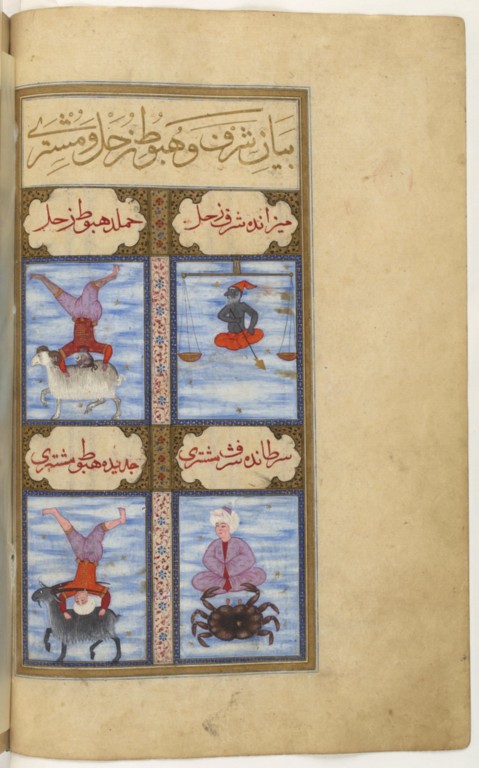

Representations of the planets are found in the artistic traditions of many cultures in which astronomy was an important science, including the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hellenistic, Indian, Byzantine, Islamic, and Chinese spheres. A possible early figuration of the planet Saturn can be seen on this ancient papyrus fragment in the Metropolitan Museum of Art as an Egyptian deity (Fig. 2). A much later figuration of the planets is found in this sixteenth century “Book of Felicity” (Matali’ al-saadet) made for Sultan Murad III (r. 1574–1595), now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which contains images of the “exaltation” and “dejection” of the planets—that is, when they are in apogee and perigee (Fig. 3). On folio 33v, Saturn’s exaltation in Libra is represented by the zodiacal scales, and his dejection in Aries shows him falling headfirst onto the back of a ram. The lower two vignettes similarly depict Jupiter’s exaltation in Cancer by pairing him with the zodiacal crab, and his dejection in Capricorn by tumbling onto a goat.[3]

In western European art, the planets were presented both as heavenly bodies and in symbolic form. In this late medieval manuscript of the Confessio Amantis (“The Lover’s Confession”) by John Gower, a small miniature of the planetary system, prefacing the part on Astronomy, contains the sun and moon with human faces among five gold and starry planets, the uppermost two labeled with their Latin names “Saturnus” and “Iubiter” (Fig. 4).

In Dante’s Divina Commedia, the spheres of heaven were represented by planets; Saturn was the seventh sphere and Jupiter the sixth. In this illustration of Paradiso 22, the scene of the “Heaven of Saturn” is portrayed by Beatrice and Dante welcoming five nude souls descending a ladder from a glowing red star with seven points (Fig. 5). Reading the Paradiso, we know that this level of heaven was reserved for the contemplanti, or the founders of monastic orders, “men who were kindled by that heat which brings to birth the blessed flowers and blessed fruits.”[4]

In other medieval works the planets of the cosmos (and sometimes their children!) were personified as human figures.[5] In some of the earliest examples, planets were depicted as crowned figures, triumphant generals, or wearing laurels, rayed headpieces or wings; such types appear on Roman coins and as bust-length personifications in illustrated poems known as carmina figurata.[6]

Some representations evoked the temperaments often associated with each planet. Associated with the ambivalent nature of melancholy, Saturn was often configured as an old man with a handheld sickle (or a more “modern” scythe) and with a cloak draped over his head, but he can also hold a shovel, a wheel, and small nude figure, which he raises up as if to devour, a reference to the Greek myth in which he swallowed his children.[7] Jupiter was seen as a protective deity: his iconography varies from the classical, bearded archetype of “Zeus Pater” (Zeus the Father), who brandishes lightning bolts, a celestial wheel, or other symbols of his power, to his personification as a bishop in a late fifteenth-century astronomical miscellany in the Getty Museum.[8]

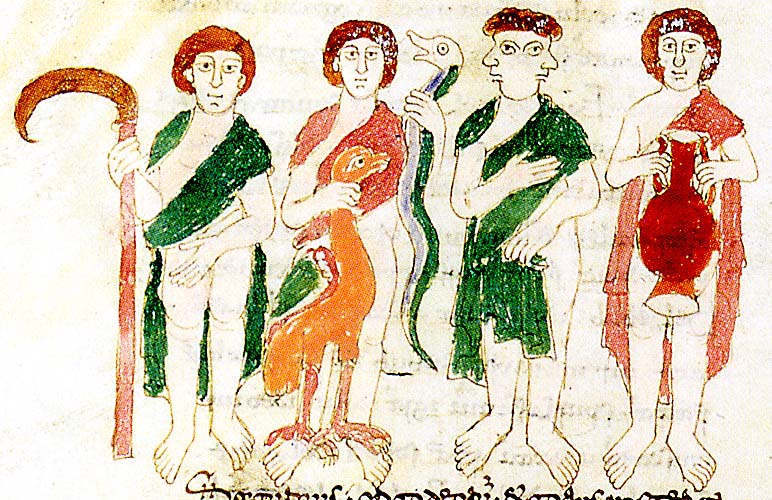

In classical mythology it was held that Jupiter drove Saturn away from his celestial throne. A marginal scene in this ninth century Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen depicts this dramatic argument of the ancients (Fig. 6). Saturn is pursued by Jupiter both wielding an axe, illustrating the First Invective against Julian the Emperor, “… let Jove rebel against Saturn, following his sire’s example; that sweet stone and bitter slayer of tyrants …”[9] In an early eleventh century manuscript of Rabanus Maurus’s encyclopedic De Universo, one miniature depicts Saturn with a scythe, nearly as tall as he, and Jupiter holds a symbolic pair of attributes: an eagle for deified justice and a serpent representing the age-old struggle for it (Fig. 7).

Two highly emblematic representations of the planets Jupiter and Saturn appear in the Rheinish manuscript of the Von Dem Gang des Himmels und Sternen (“The Course of the Heavens and Stars”), forming its own “planetary conjunction” at the close of the book (the miniatures are on facing pages). Both planets, Saturn personified as a simple farmer and Jupiter as city patrician, are decorated with imagery from a number of astrological and zodiacal sources, including their corresponding symbols for Libra and Cancer (Figs. 8 & 9).

The Index of Medieval Art database includes much more in the way of celestial imagery, including subjects related to the iconography of the other planets, stars, zodiac symbols, and constellations. The database also can be keyword searched for other named astronomical objects, such as “Star of Bethlehem.” These examples appear in a wide variety of works of art, including almanacs, calendars, astrological treatises, constellation maps, zodiac cycles, and a variety of narrative and allegorical works, and across different media, cultures, and periods.

The planetary motions of Saturn and Jupiter have been described by astronomers, such as Newton, Kepler, and Laplace, as “The Great Inequality,” meaning that while Jupiter’s mean period of motion is continually increasing, Saturn’s is continually diminishing and falling further behind.[10] Thus, both planets have long been approaching each other in the same direction, yet with enormous discordance.

The year 2020 has had its own prelude of tumultuous moments leading up to this great planetary conjunction. As the globe still grapples with a challenging year, it’s easy to imagine this alignment of Saturn and Jupiter as a sort of “clash of the titans,” but when we look west in the sky just after sunset, let us recall that this special occurrence, a most rare ballet of the planets, also marks a new season that will bring more light to our days.

[1] O’Neill, Mike. “Don’t Miss It: Jupiter, Saturn Will Look Like Double Planet for First Time Since Middle Ages.” SciTechDaily, 23 Nov. 2020, https://scitechdaily.com/dont-miss-it-jupiter-saturn-will-look-like-double-planet-for-first-time-since-middle-ages/; Strickland, Ashley. “Jupiter and Saturn Will Look like a Double Planet Later This Month.” CNN, Cable News Network, 3 Dec. 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/12/03/world/jupiter-saturn-conjunction-2020-scn-trnd/index.html; Levenson, Michael. “Jupiter and Saturn Head for Closest Visible Alignment in 800 Years.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Dec. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/06/science/space/jupiter-saturn-align-christmas-star.html.

[2] Douglas, A. Vibert, “Historical Significance of Five Conjunctions, 1226–27,” Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 65 (1971): 129–132.

[3] See also this exquisite engraved and inlaid brass tray with personifications of planets made by Mamluk craftsmen and commissioned by a Sultan in Yemen in the early fourteenth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.1.60). For more on astronomy and astrology in the medieval Islamic world, see this essay by Marika Sardar: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/astr/hd_astr.htm.

[4] Paradiso 22, 47–48 accessed at Barolini, Teodolinda. “Paradiso 22: Controlled Orphism.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2014. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-22/. See also the Princeton Dante Project https://dante.princeton.edu/pdp/, with recent news and developments on the project here, https://humanities.princeton.edu/2020/11/29/2020-rapid-response-grant-literary-visualizations-reconstructs-imaginations-of-dantes-readers/.

[5] Discussion of the planets and their characteristics, temperaments, and affinities are found in many almanacs, planet books, and other cosmological treatises. See especially the classic Warburgian study by Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art (London: Nelson, 1964). Reissued by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019.

[6] The Index database records three examples of planetary carmen figuratem, all in the British Library, MS. Cott.Tib.B.V (fol. 44v), MS. Cott.Tib.C.I (fol. 33r), and MS. Harley 647 (fol. 13v).

[7] Klibanksy, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 197.

[8] For the Jupiter-Bishop on horseback see Getty Museum, MS. Ludwig XII 8 (83.MO.137), fol. 49v. See also the Art Stories post by Bryan C. Keene, “Written in the Stars: Astronomy and Astrology in Medieval Manuscripts,” Getty Iris Blog (30 April 2019), https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/written-in-the-stars-astronomy-and-astrology-in-medieval-manuscripts/.

[9] See lines 120–121: Gregory Nazianzen, “Julian the Emperor” (1888). Oration 4: First Invective Against Julian. The Tertullian Project, 14 Dec. 2020, http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/gregory_nazianzen_2_oration4.htm.

[10] Wilson, Curtis, “The Great Inequality of Jupiter and Saturn: From Kepler to Laplace,” Archive for History of Exact Sciences 33, no. 1/3 (1985): 15–290.

As the fall 2020 semester begins and the Index staff continue to work remotely, each of us connecting from different locations, our home libraries and desks have become essential tools in our research. They call to mind medieval images in which the scribe’s desk and well-stacked bookshelves are familiar iconographic attributes of the Evangelists, as well as theologians, scholars, physicians, and literati, as they labored in their study spaces (see Index subjects: Bookcase, Scholar, Physician, Literatus, and Philosopher Type). Their desks took a variety of forms and shapes, from tall book stands or lecterns, sometimes decorated with animals, birds, and foliage, to round or squat tables of a simpler design. Medieval images of scribes and writers often show the surfaces of their desks covered with open books or sheets, some with scrawled lines (search Index keyword: pseudo-inscriptions), inkhorns and inkpots, knives, pen cases, and a spare stylus or two.

Working in a modern study space, many of these similar tools are within my reach: pens, scissors, a pencil cup, and plenty of Post-it Notes containing my jotted reminders—arguably legible! My computer desktop is a hub for images of medieval works of art, articles, and spreadsheets that help organize my Index work. To the right of me, sits a modest collection of tomes (to name a few, Emile Mâle’s Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages; Roger Wieck’s Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art; Baxter’s Bestiaries and Their Users in the Middle Ages, and the catalogues The Splendor of the Word and The Golden Age of Ivory Gothic Carvings in North American Collections). Some books are my own and some are out on temporary loan from the Index’s research library and from Firestone Library, but all are bolstering this new environment of cataloguing and scholarship from home.

For Index research staff, this means that our working desktops (both physical and virtual) and our carefully curated home libraries (whether lining our walls or nested digitally into desktop folders) will support our ongoing remote activities. This semester, we will continue to pursue new art historical research for additions to the database, including works from the original print backfiles, from monumental mosaics to illuminated manuscripts and ivory objects. We remain focused on expanding the Index collection to present the rich array of iconography from the global Middle Ages. We will also continue to refine the database by building and improving work of art location authorities, further developing Index subject classifications that improve thematic browsing, and implementing the new hierarchical browse tool for researching the placement of medieval iconography within structures. Above all, we will remain available to support researchers at all levels in their use of the online Index database.

Wherever you may be this term—whether you feel like a monk in a cell or a monkey with an inkpot—we hope that you are well and looking forward to your study, surrounded by the tools of your scholarship. We look forward to hearing how we can help serve your research and teaching in the upcoming academic year.

In northern climes, the beginning of February used to be reliably miserable. It was always the time of year when the sedentary heart of winter was covered in forgetful snow, and we took refuge indoors while the wasteland outside was feeding a little life with dried tubers (to paraphrase T.S. Eliot). Groundhog Day is in early February for a reason. Every year, in our collective longing for an early return of spring, we eagerly anticipate the meteorological insights of a skittish marmot. And so, despite the unseasonably warm temperatures in Princeton this week, we couldn’t help but explore some imagery traditionally associated with the month of February.

In many manuscript calendar illustrations, the occupational image for February depicts an interior scene, a room in which figures warm themselves before a fireplace. Seated at the hearth, a female servant, or perhaps the woman of the house, stokes the fire. Often in such scenes, a man sits at a table spread with food and dishes. The Index of Medieval Art subject heading identifies this scene as the “Labors of the Month, February.” Certain components of this subject, such as “Fireplace,” “Table,” and “Feasting,” also have their own subject designations.

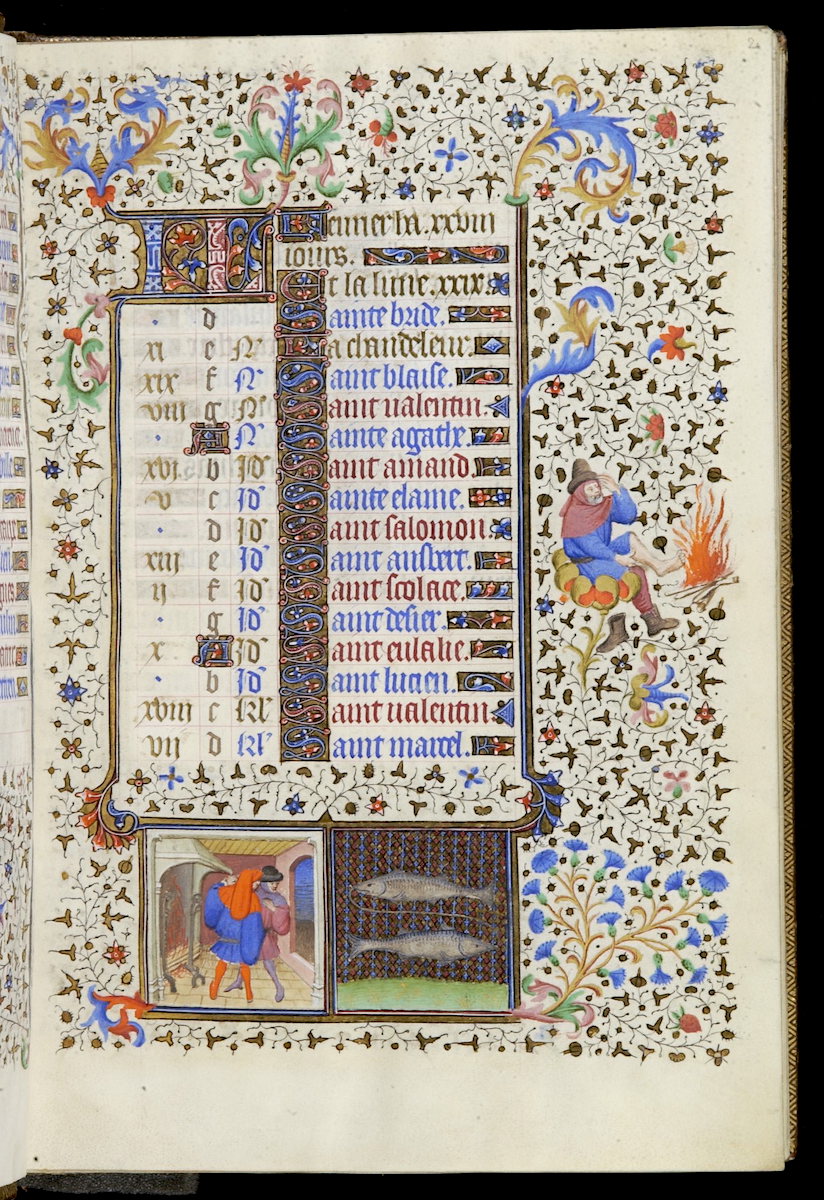

Other attributes common to the February warming scenes are figures performing such actions as blowing a bellows at the fire, cooking food in a pot over the flames, carrying bundled firewood indoors, or wearing heavy furs. A marginal miniature in the calendar of a fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Burgundy depicts a typical February scene with several of these domestic elements: a woman wearing a veiled headdress stokes a glowing fire in a simple stone fireplace while, behind her, a warmly dressed man seated at a draped table clings to a morsel of food (Fig. 1).

Searching the Index of Medieval Art database with simple keywords such as “fireplace,” and using the Subject Filter for “Labors of the Month, February,” will return a little more than seventy work of art records. Most of them appear in illuminated manuscripts. One such fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Paris or Flanders contains a February calendar page with two square miniatures of equal size in the lower margin. One of these paired miniatures shows the typical interior occupation of February, figures by the fire. The other shows the usual zodiac sign, Pisces, as a pair of fish lying head to tail with a line connecting them by their mouths. In the right margin, the artist created a comical moment: among the densely scrolled foliate borders, a man sitting on a fantastic flower raises his bare left foot toward some blazing logs (Fig. 2). In February, even marginalia need to warm their toes!

Other database filters will discover results illustrating February in different media, such as a man warming himself in the quatrefoil stone relief sculpture on the west façade of Amiens Cathedral. While this February figure sits and adjusts logs on the fire, his shoes are neatly placed in the foreground (Fig. 3). As is common for all twelve labors of the months, iconographic variants occur among these images, and monthly tasks are not fixed. Indoor cold weather occupations—including feasting, cooking, and baking—can be found in the previous months of January and December, often in similar compositions with fireplaces. February illustrations may also show outdoor scenes, such as slaughtering animals, fishing, digging fields, or pruning vines.

Keeping warm and dry during the winter months was a matter of survival for medieval people. Even today our good health and happiness are at risk in the winter. While its fires are long extinguished, this fine fifteenth- or sixteenth-century French limestone fireplace, today on display in the Met Cloisters, was likely once the architectural centerpiece of a home, and we can still imagine its appealing warmth (Fig. 4). Whether you are enjoying a restfully sedentary season or the official start of the spring semester has you thoroughly engaged in your own labors of the month, we wish you a warm and happy February!

As a victorious angel, defender, and leader of heavenly armies, Michael the Archangel is often depicted in medieval art as an armored soldier carrying such arms as a cross-inscribed shield, cross-staff, or the sword or spear he typically employs to fight the dragon in the “great battle of heaven” (Apocalypse 12:7–9; see the Index subject Apocalypse, Dragon Attacked by Michael). Outside of the apocalyptic combat scene, Michael also may be shown trampling and piercing the dragon as part of his overall iconography. This figuration of Michael as the triumphant archangel lent a devotional and meditative aspect to his veneration as an overcomer of evil, as is often clear in images related to the Christian feast of Michaelmas. The feast’s name in English derived from “Michael’s Mass” and is traditionally observed in some Western churches on the 29th of September. While Michaelmas was primarily celebrated to acknowledge the works of Michael the Archangel, this feast also celebrated the help and intercession of all angels. Michaelmas also bore secular significance for medieval people as a “quarter day” of the financial year, which signaled the fulfillment of various business obligations, and the close of the agricultural year (For more on this holiday, see Ben Johnson, Michaelmas, The Blog of Historic UK).

At this time of Michaelmas, a dive into the online collection of the Index of Medieval Art reveals a wealth of examples tied to the iconography of the revered archangel. The most common representation is of Michael the Archangel fighting the dragon. In the language of the Index, that’s Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Dragon. This subject heading is attached to nearly 300 works of art in the database applied to a variety of media, including a Romanesque limestone relief panel from Burgundy, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris (Fig. 1). A closely related subject, Michael the Archangel, Transfixing Satan, is applied to works of art in which the dragon has morphed into a devilish creature, usually shown with horns and clawed feet. Like the hapless dragon, this creature is similarly impaled and trampled! Exploring these two similar subjects reveals a later preference for the literal depiction of devils in place of dragons. Michael the Archangel also features in other important episodes, such as the biblical narrative of the Fall of Angels and the Last Judgment of Christ (Figs. 2 & 3). In Last Judgment scenes, Michael the Archangel is often shown holding the scales of justice laden with good and bad souls (See the Index subject Weighing of Soul).

A fifteenth-century alabaster panel from England combines many aspects of Michael’s typical iconography: here, wearing a suit of armor that resembles feathers, he also bears a shield and raises his sword over the vanquished dragon. One weighing pan of his scales remains, holding a devil head, while behind him, a crowned Virgin intercedes to emphasize mercy with justice (Fig. 4).

In the Index database, Michael the Archangel is by far the best represented of the archangels, with thirteen subjects covering his various roles, from intercessor and commanding soldier to apparition in visions and legends. A common legendary context for Michael is that of the “Runaway Bull” in the Golden Legend. According to the legend, a wayward bull belonging to Garganus, a wealthy man from Siponto, is miraculously saved from the shot of an arrow, which instead reversed in midair and killed the huntsman. As an explanation for this strange occurrence, Michael the Archangel appears to a local bishop to reinforce the idea of grace at the bull’s saving and to tell him to build a church in his honor (Fig. 5). The hilltop sanctuary of San Michele del Gargano is still a popular site of pilgrimage in the town of Monte Sant’Angelo in southern Italy.

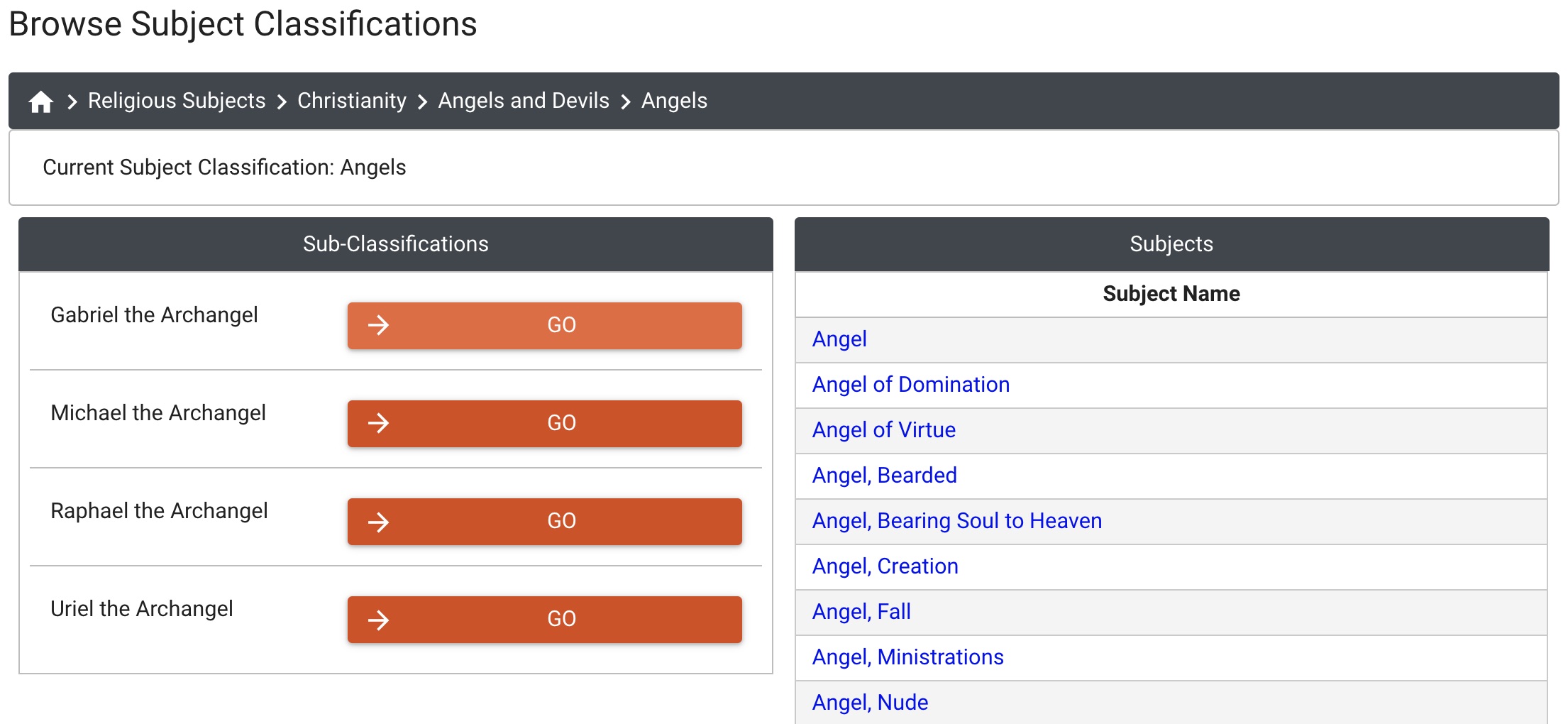

For a more general overview of the iconography of angels in the Index database, we encourage you to browse sections of the new subject classification network by clicking “Browse” and proceeding to the link for “Subject Classification.” From here, click on Religious Subjects, then Christianity, then Angels and Devils. In the sub-group of Angels, you will encounter a list of over twenty iconographic headings associated with various angels, including seraphs, cherubs, and several more subjects for angels engaged in specific actions, such as “Protecting Soul” and “Pursuing Devil.” On the left are further divisions for the four major archangels of Christian angelology—Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, and Michael—which list the individual subjects related to each. At the bottom of each authority for these subjects, you’ll see a bar for “Work of Art References” that will take you to the relevant work of art records.

This summer The Index of Medieval Art welcomed two students from the Master of Information program at Rutgers University to inventory the Index’s photographic archive. Comprising nearly two hundred thousand cards in sixteen different medium categories, this historic image collection provides researchers a rich resource of sometimes rare visual references for the study of art produced throughout the Middle Ages. The inventories undertaken by Ryan Gerber and Michele Mesi have illuminated the extent of the archive and helped to assess the image and cataloguing needs for ongoing research and cataloguing at the Index. In this special two-part blog post, we are pleased to present their observations and accounts of their experiences.

It is a testament to the Index’s stimulating power that, despite my lack of an art-historical background, I found myself entranced by the system of cataloguing medieval iconography that the Index pioneered and is still practicing to this day. Its vision of greater accessibility through complete digitization represents another milestone in its long history, and one which will be a gift to scholars of all persuasions and experience levels.

A system largely developed by Index director Helen Woodruff in the 1930s, the photographic archive is organized in the first place by medium, then by location, object type, and the numeric order within that group. Unique codes on the left-hand corner of every index card in the catalogue represent each of these levels of organization. The fruits of this labor are hard to miss after spending any time with the Index and its elegantly interwoven subject index and photographic archive, where one can move seamlessly from subject description to pictorial representations and vice versa.

This work has also left behind a trove of archival resources such as hundreds of rolls of film and the so-called “Black Books” that were used to track the negative numbers. Each of the medium categories I inventoried not only laid the groundwork for further analysis of the collection as a whole, but highlighted the Index’s remarkable century-old ability to generate new curiosities and paths of inquiry.

Terracotta, Temporary Cards, Lamps, and Lions

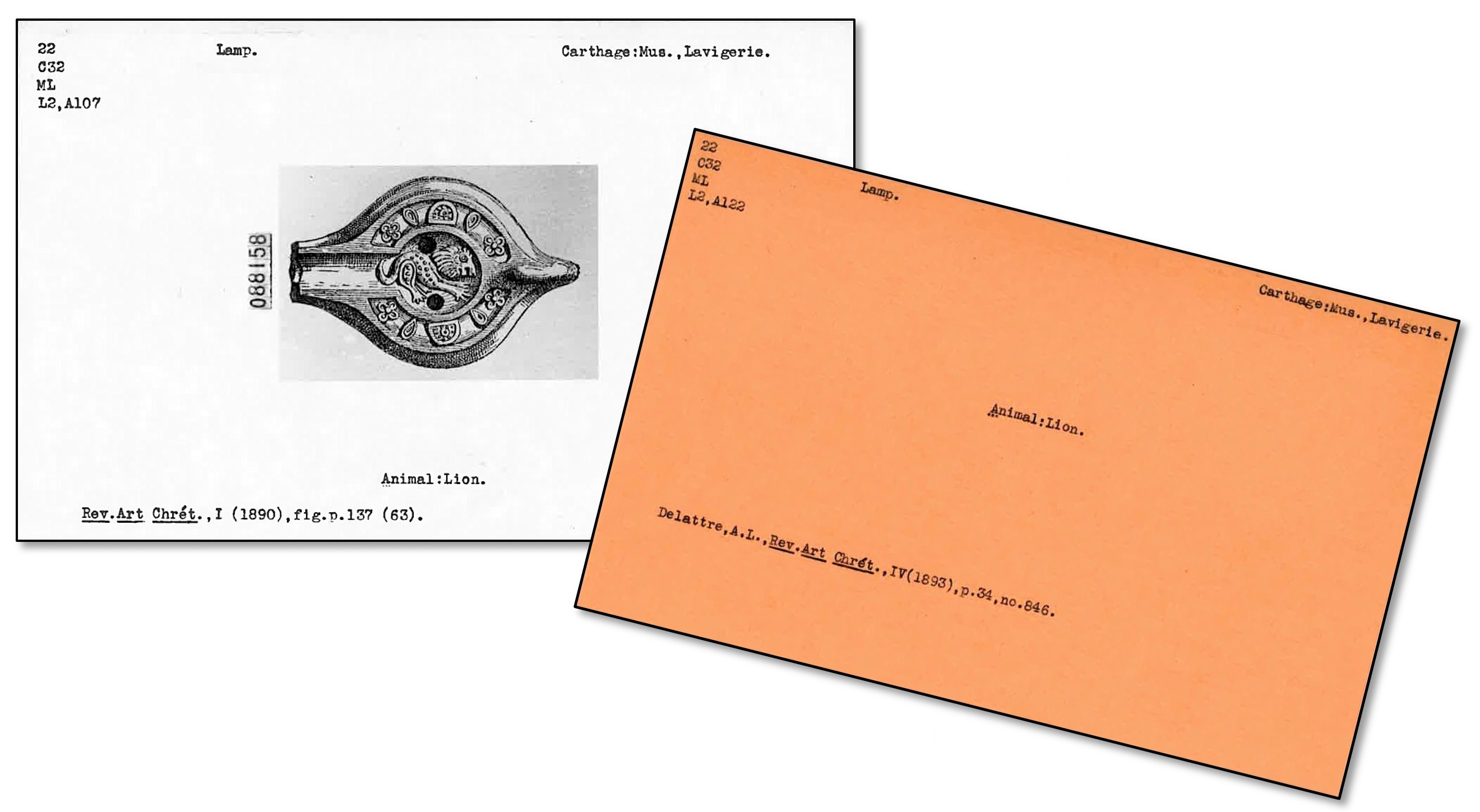

Under the medium “Terra Cotta”—a mixture of clay and water that is formed and baked or fired—the Index records more than twenty-five hundred objects across 196 locations. Of these objects, about sixty-five percent of them are oil lamps. The inventory of these files revealed some of the more common iconographic motifs found on terracotta objects, which include foliate ornament, a variety of land animals and birds, symbols such as crosses, as well as inscriptions and monograms. One terracotta lamp from the Benaki Museum in Athens depicts two of these popular motifs—a lion and a tree—combined on one impressed discus (Fig. 1).

Most photograph cards contain representations of the objects, but they also record the object’s location, the photograph’s negative numbers, subject headings for the image or images on the object, and some bibliographic information. However, there are many temporary “Orange Cards” in the archive that contain only a bibliographic reference and a subject term, and these still await corresponding images. Their inclusion in the original system nonetheless provides important data points about the objects they describe, laying the groundwork for future cataloguers to source the images for these object records. For example, the Index’s photo archive of terracotta objects in the National Museum at Carthage is mostly Orange Cards because the original Index records of these objects derive from a 19th-century publication with very few illustrations. While it would be useful to see images of the “lions” held at the National Museum in Carthage, even in the absence of photographs it may be just as useful to know that, of the 970 terracotta lamps held in that location, nearly four hundred depict animals, and about sixty-five of those include a lion.

A Face in Gold Glass

The “Gold Glass” files record over 650 objects across sixty-three locations dating mostly from late antiquity between the 3rd and 7th centuries. Of these objects, nearly half are vessels of some kind. Gold glass developed as a medium in the ancient Roman and Hellenistic periods and consisted of decorative engravings made in gold leaf, which were then sandwiched between fused layers of glass. The result was lavish decoration, and exemplary pieces in this medium offer strikingly detailed portraits of their subjects, often depicting married pairs, family groups, or religious figures associated with one another, such as Saints Peter and Paul. Historians have noted the rarity of gold glass, as well as its costly, specialized method of production.[1]

Gold glass was a special interest of Index founder Charles Rufus Morey, and his pioneering catalogue of the Vatican Library’s collections features as its first entry an example also catalogued by the Index. It shows the busts of a married couple inscribed above with the name Gregori and a Latin equivalent of “cheers!”: “Gregori bibe [e]t propina tuis,” or “Gregory, drink and drink to thine!” (Fig. 2).[2]

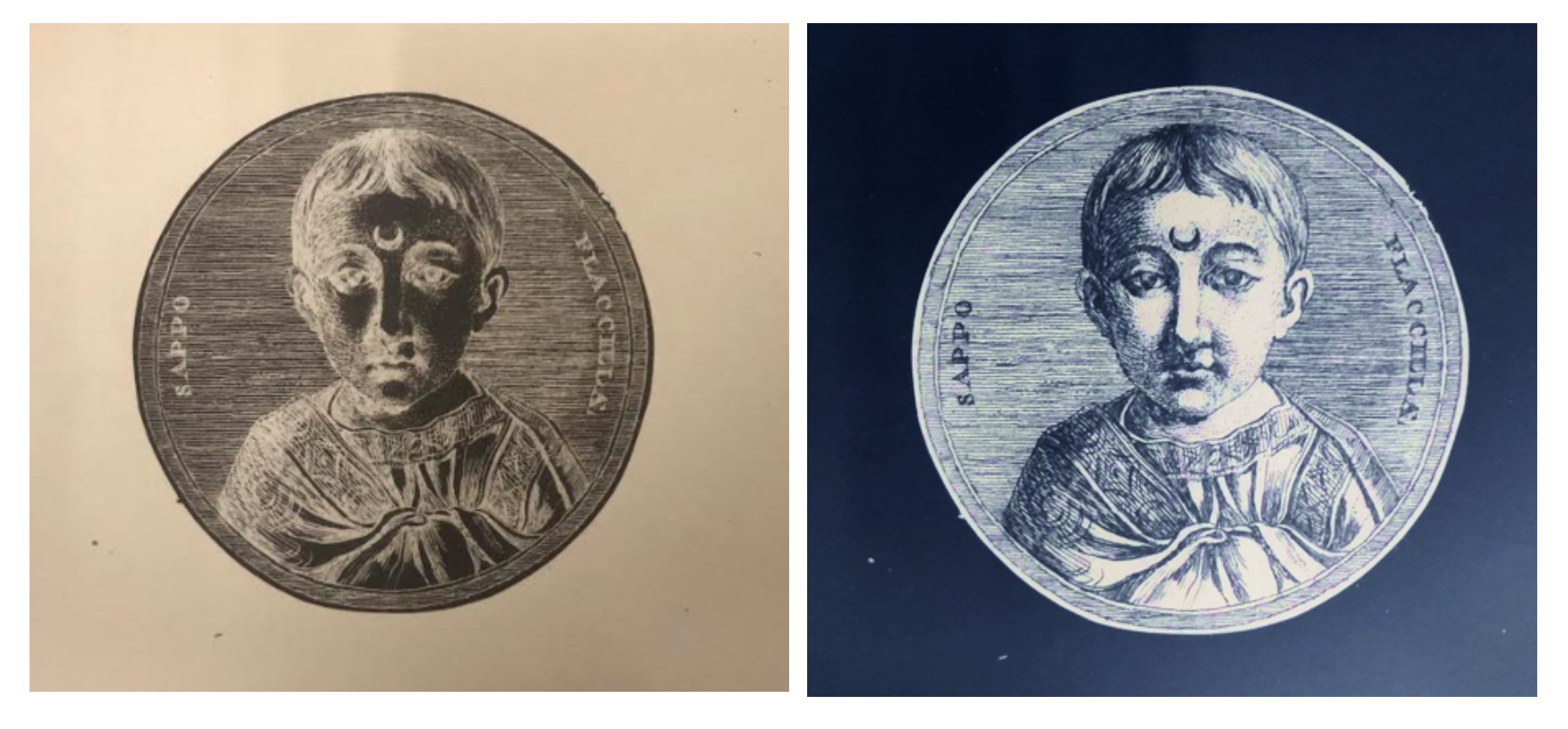

Another interesting discovery in the “Gold Glass” category was a round vessel fragment last recorded in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris. It depicts a striking bust of a figure with shorn hair, dressed in a trimmed tunic, and with a distinctive crescent shape on their forehead. The only other information on the photograph card was the source of the image, the antiquities catalogue that Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus published in seven volumes from 1756 to 1767.[3] Caylus’s catalogue was a valuable starting point for identifying this figure, whose iconographic description had not been entered in the Index’s subject files or the database. A little more searching led to a color image in a French catalogue, the Histoire de l’art de la Verrerie dans l’Antiquité (Fig. 3), and to the conclusion that the inscription “SAPPO FLACILLAE”—with the genitive form of the empress’s name—referred to a branded enslaved person who had been freed by the Roman Empress Aelia Flacilla (356–386). We also used the photo-editing web application Pixlr to create a positive image of “Sappo” so that the image from the Index archive can now be seen as it appeared in the catalogue of the comte de Caylus (Fig. 4).

Impressions in Wax

Comprising a little over one thousand objects in 105 locations, the “Wax” medium files are overwhelmingly made up of stamps from Europe dating largely to the 13th and 14th centuries. Although the archive groups these objects into the single object category “Stamp,” the Index database divides them into two Work of Art Types, “Seal Matrix” (that is, the tool used to make the impression) and “Seal Impression” (that is, an impression made by a matrix).[4] Viewing about a thousand examples of Gothic seals intended for both religious and secular officialdom brought into literal relief the development of the production of seal dies from simple figural representations to complex ecclesiastical chapters in miniature, such as the Stamp of Ely Priory, dated to about 1240–1260 (Fig. 5). Other favored subjects in wax seals include heraldry, nobles, and popular saints and bishops, like Thomas Becket. The wealth of iconographic information in the “Wax” files—indeed throughout the archive—emphasizes that the Index is not a closed system, and has at every turn great potential for leading one into new areas of inquiry.

Ryan Gerber is a graduate student at Rutgers University studying Information Science with a concentration in Archives and Preservation. He holds an MA in English from The College of New Jersey with a concentration in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. His interests include digital preservation and retrieval, the digital humanities, and information behavior.

See Part 2 written by Michele Mesi.

[1] Giulia Cesarin, “Gold-Glasses: From their Origin to Late Antiquity in the Mediterranean,” in Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millennium AD (London: UCL Press, 2018), 22–45.

[2] Morey noted of the inscription that “the E of ‘bibe’ or of ‘et’ [was] omitted by mistake.” Charles Rufus Morey, The Gold-Glass Collection of the Vatican Library (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1959), 1. Translation after Georg Daltrop in Leonard von Matt, Georg Daltrop, and Adriano Prandi, Art Treasures of the Vatican Library (New York: Abrams, [1970]), 168.

[3] Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus, Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, greques, romaines et gauloises (Paris, 1756–57), 193–205, pl. 53.2, https://archive.org/details/recueildantiquit03cayl/page/n10.

[4] See the Index database Work of Art Type browse list to access these Work of Art References.