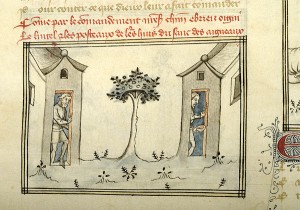

Detail of Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent. Old Testament Picture Book. French, c. 1250. Morgan Library, M.638, fol. 8r

Nine times Moses went to the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II to demand freedom for the Israelites in captivity, saying “Let my people go.” Each time Moses and his brother Aaron were sent a way, an episode classified by the Index as, Moses and Aaron: driven from Pharaoh’s Presence. Despite these increasingly tense exchanges, and then a marvelous act that changed Aaron’s rod into a serpent before the Pharaoh’s court (Moses: Miracle of Rod changed to Serpent), Ramses still refused to release the Israelites from slavery.

What followed was the foretold wrath of God enacted as ten crippling plagues on the Egyptians. In the first wave of calamities, there were plagues of blood, frogs, gnats, and lice that polluted the air and water. The second wave, brought plagues of flies, diseased livestock, and boils. Then came hail, locusts, and darkness that fell on Egypt for three days. The tenth and final plague, the “Plague of the Firstborn,” claimed the lives of the eldest children in all Egyptian families. The Index of Christian Art classifies the subjects of the Exodus plagues under the major figure of Moses:

Moses: Plagues of Flies, Frogs, Locusts, Hail and Pestilence. Stuttgart Psalter, c. 820-830. Stuttgart Landesbibliothek, Bibl.fol.23, fol. 93r. Photograph by Gabriel Millet.

(Exodus 9:6-7)

The final plague is described in several phases throughout the books of Exodus (11:4-8; 12:1-13, 21-23, 29-30). Moses first warns of its coming to the embattled Ramses, but his warning is dismissed.

Facing the impending deadly plague, Moses instructs the Israelites to make a sacrificial offering to God, and to use the blood of the animal – a male yearling – to mark the doorposts and lintels of their homes. Moses explains to them that marking their homes this way will spare their firstborn children from the “death angel,” saying he “will pass over the door.” (Exodus 12:23).

Moses: Plague of Firstborn. Two Israelites marking the doorposts and lintels of their homes with the blood of the sacrificial lamb. History Bible, Paris, c. 1390. Morgan Library, M.526, fol. 14v

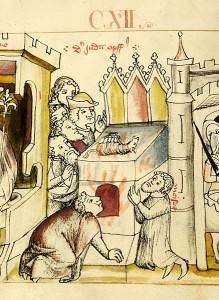

Detail of Moses: Passover. Israelites cooking the sacrificial lamb under the inscription “Die Juden Opffer.” Historien Bibel, Swabia, late 14c. Morgan Library, M.268, fol. 7v

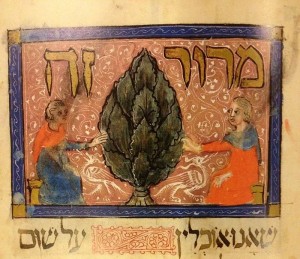

Following this, the Israelites were delivered from bondage and departed from Egypt. The Exodus is remembered at the feast of Passover – the Hebrew feast of Pesach – with special instructions for preparing, eating, and storing traditional, often symbolic food. While Passover traditions have varied over time and from one region to another, it is generally a family holiday in which the meal is accompanied by readings, songs, and traditional rituals designed to remind the celebrants of the Exodus story and the hopes for a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. The order of the seder, or Passover meal, is set out in a book known as the Haggadah, which was sometimes richly illuminated in the Middle Ages, as shown here in the Sarajevo Haggadah, originating in Barcelona in the middle of the 14th century. Well-known related manuscripts to this Haggadah include the Rylands Haggadah and the Simeon Haggadah. The Index classifies subjects depicting the original Passover feast as Moses: Passover, Moses: Passover proclaimed, and Moses: Law, Feast of Passover and with a general heading for Scene: Passover.

Bitter herb or “maror” in the Sarajevo Haggadah. Barcelona, c. 1350. Sarajevo, National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photograph Wikimedia Commons.

Celebrated annually on February 14 as a day for courtship and romance, Valentine’s Day began as a liturgical celebration in honor of one or more Early Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The Roman Martyrology mentions two Valentines, both of whom were decapitated on the ancient Via Flaminia, the main artery connecting the city of Rome to the Adriatic Sea. One Valentine died in Rome and seems to have been a priest. The other, who may have been a bishop, was martyred approximately 60 miles away at Interamna (modern Terni).

The earliest extant connection between Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (1383): “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” February 14 was associated with courtly love as early as 1400, in a charter ostensibly issued by Charles VI of France (d. 1422). The text describes the festivities of the royal court, which included love poetry competitions, dancing, jousting, and a feast. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm evidence linking Valentine’s Day with the ancient Roman Lupercalia, a pastoral festival observed from February 13 through 15 to purify the city of Rome and to promote health and fertility.

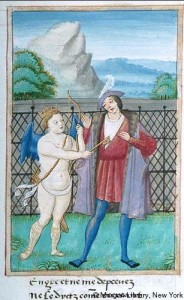

The Index of Christian Art is delighted to present four images thematically associated with Valentine’s Day. First, the nimbed Valentine of Rome is represented with the sword of his martyrdom in the fifteenth-century Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Morgan Library, M.917 and M.945). Second, a sixteenth-century Roman de la Rose contains a charming depiction of the God of Love locking the Lover’s heart with a giant key (Morgan Library, M.948). Third, a fourteenth-century ivory box cover of Parisian origin shows women defending the castle of love, a popular subject in late medieval courtly circles. The winged god of love at the top of the roundel prepares to launch his arrow, while women throw flowers at the attacking knights. Last, a sixteenth-century drawing from an Arma Christi and Prayers (Princeton University Library, Taylor 17), which portrays Christ’s heart with three blossoming flowers, is inscribed pyte, love, and charyte.

Shepherd at the Nativity. Fourth century sarcophagus. Arles, Musée de l’Arles et de la Provence Antique, FAN.92.00.2517. Index system number 000107697.

Of all the medieval images associated with the Christmas story, surely most familiar is that of the Nativity, which depicts the Christ child in the lowly stable of his birth, almost always attended by the Virgin Mary, her husband Joseph, and the ubiquitous ox and ass. Medieval nativity scenes often included other onlookers as well, from the shepherds and magi to whom angels announced Jesus’ birth to the midwives who, in some accounts, assisted at it. Of all these figures, few have a longer or more engaging history than the shepherds, with whose homespun character and simple faith many ordinary medieval Christians could identify.

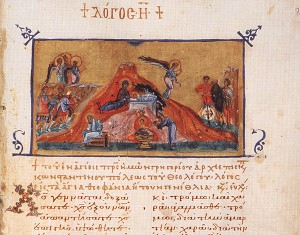

Shepherds and Magi at the Nativity. Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen, 11th century. Jerusalem: Greek Patriarchal Library, MS Taphou 14, fol. 80r. Index system number 150818

The shepherds themselves have biblical origins: Luke 2:8-20 describes them receiving news of Christ’s birth from a host of angels, then rushing to the stable to see the child for themselves. The scene of the angelic annunciation to the shepherds is sometimes presented adjacent to or in the background of the Nativity, and in the very late Middle Ages, under the influence of Franciscan piety, it was also depicted as an independent scene. However, from the beginnings of Christian art, the shepherds were also frequent onlookers at the Nativity itself. By the fourth century, Roman and Gallic sarcophagi had begun to include one or two shepherds standing beside the manger, often raising a hand in recognition of Jesus’ divinity; middle Byzantine mosaics often cast the shepherds as a trio to balance the three magi who also attended the child. Such pairings were encouraged by medieval texts that presented the shepherds as symbolizing the Jewish tradition from which Christianity had sprung and the magi as representing those pagans who converted to the faith. Alternatively, the magi and shepherds were sometimes presented as demonstrating Christ’s recognition by all walks of life, a universalistic message sometimes developed further in the portrayal of both groups as men of varying ages and even ethnicities.

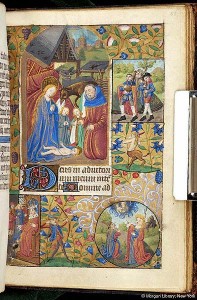

Music-making shepherds on the margin of the Nativity, ca. 1470. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS m.32 fol. 51r, Index system number 000175635

Late medieval pietistic trends, which promoted the idea that the poorest of men had been the first to receive news of Christ’s birth as confirmation of the value of humility and simplicity, encouraged fourteenth- and fifteenth-century artists to elaborate their images of the shepherds. They often are shown as rough-hewn peasant types—sometimes even including a shepherdess—who offer the child simple, heartfelt gifts, such as a lamb, a flute, flowers or, more unusually, a basket of eggs. The appeal of these humane, familiar figures still resonates in many a Christmas sermon as well as Christmas carols, from the traditional Austrian “Shepherd’s Carol” to the 1941 pop hit “The Little Drummer Boy.”

Shepherds are noted in over 650 records of the Nativity in the online database of the Index of Christian Art; many more can be found in the card files. Media include sculpture, gold glass, manuscripts, enamel, mosaic, fresco, and painting. We wish all our friends who celebrate Christmas a joyous and peaceful holiday.