The Index is pleased to announce the speakers for two honorary sessions at the International Congress on Medieval Studies to be held at Western Michigan University (Kalamazoo, MI) on May 11-14, 2017.

Organized by Judith Golden and Jessica Savage, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Presider: Judith H. Oliver, Colgate University, Professor Emerita

This session will examine the interaction between words and images in medieval manuscripts as they shape the reader-viewer’s experience of the book. How do texts and images interact on the page? How did medieval readers respond to the varied discourses between images and texts? This session endeavors to open up new perspectives in describing, analyzing, and contextualizing manuscript illumination according to their intrinsic or peripheral textual elements. Papers in this session will undertake a close study of a particular manuscript and will expand upon theories for image-text composition by reviewing evidence of an artist’s written instructions; reading images with layered text additions, omissions or annotations; and recovering the reader’s experience through text and iconography.

“Artists and Autonomy: Written Instructions and Preliminary Drawings for the Illuminator in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea (HM 3027)”

“Bodies of Words: Text and Image in an Illustrated Anatomical Codex (Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 399)”

“A Votive ‘Closing’ in the Claricia Psalter (Walters MS W.26)”

Presider: M. Alison Stones, University of Pittsburgh, Professor Emerita

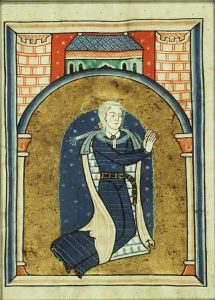

This session will examine the varied “visual signatures” of manuscript patrons, including dress, gestures, posture, and attributes of donor figures; heraldry and personalized inscriptions; marginal notes, colophons, dedications, and other signs of ownership and use in medieval manuscripts. Building on scholarship presented in the 2013 Index of Christian Art conference Patronage: Power and Agency in Medieval Art, this session will investigate the dynamic system of patronage centered on the interaction of owners with their books (whether as creator, patron, commissioner, or reader-viewer). Papers will address the importance of gender and social roles in book production, use, and readership, or will expand upon the role of patron as instigator in the book creation process, from payment to design.

“How Owner Portraits Work”

“The Patroness Portrait of the Fécamp Psalter (c. 1180): An Unknown Example of Royal Artistic Commission in Angevin Normandy”

“Patron Portrait as Creation Myth: On ‘Production Scenes’ in Illuminated Manuscripts”

In July 2016, Adelaide Bennett Hagens retired from the Index of Christian Art at Princeton University after fifty years of dedicated research and scholarship. She studied under Robert Branner at Columbia University and joined the Index during the directorship of Rosalie Green. Adelaide has studied medieval art in a variety of media, but her passion at the Index and in her personal research has always been manuscript illumination, particularly of the Gothic period. Her publications include “Some Perspectives on the Origins of Books of Hours in France in the Thirteenth Century,” in Books of Hours Reconsidered, edited by Sandra Hindman and James H. Marrow (2013); “Making Literate Lay Women Visible: Text and Image in French and Flemish Books of Hours, 1220–1320,” in Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces, edited by Elina Gertsman and Jill Stevenson (2012); and “The Windmill Psalter: The Historiated Letter E of Psalm One,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980). In two sessions, we celebrate Adelaide’s accomplishments and recognize her contributions to the Index of Christian Art and to the wider medieval and academic community.

It’s back to school time! Modern children enjoy the luxury of a school year that reflects an agrarian society, allowing time off during the summer months when all available hands were put to work in the fields. During the Middle Ages, many students lived, learned, and worked at home year round.

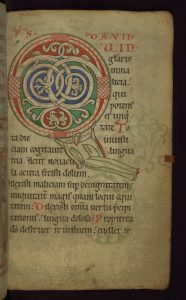

They learned how to be good citizens, and how to interact in society. They were taught basic Christian tenets and prayers. Boys learned a skill, following the family business, be it farming, blacksmithing, stone carving or brewing. Girls were taught how to run a household and the rudiments of the family business, to assist a future husband or possibly to take over business herself. In wealthier households, children learned similar life skills, but they had the advantage of becoming literate. A number of manuscripts exist that include the alphabet, Pater Noster, the credo, and familiar prayers as part of a book of hours. Under the guidance of parents, these books helped to form literate, religious offspring (Illus. 1).

Medieval art provides insights into the education of both boys and girls. Girls are shown at home, being individually tutored—as in the image of Agnes of Rome reading an open book before a seated tutor (Illus. 2)—or in small groups such as the one shown with the Virgin Mary and her mother (Illus. 3). Notably each of the girls has her own book, signaling a household of some wealth. Boys are shown at schools away from home. Jesus may be seen as a child carrying a paddle-shaped tablet with a panel of wax, slate, or parchment (Illus. 4). He is led by his mother, raising a scourge in her left hand—a view of the future, or merely an indicator of a boy who did not want to go to school? They walk toward an open-air building where the tutor holds an open book, showing the pages to several students. Other students study their own books, and several, including Jesus, wear what appear to be pen cases hanging from their belts. In another illustration, a single boy stands, perhaps reciting before the tutor, the rest of the class waiting their turns, some diligently studying open books, while one balances a book on his head (Illus. 5).

Not all were model students. Felix of Nola, whose story appears in the Golden Legend, is said to have been stabbed to death with styluses. The image here shows Felix lying on the floor of the school room, surrounded by students, one indeed holding a bloody stylus (Illus. 6). Aside from the goriness of the picture, it does give a sense of a school room. One basket, likely containing lunch, hangs on the wall while another is used as a weapon. A few books are visible, one open on a desk next to an inkpot and pen—likely a student’s blank book of either parchment or less expensive paper for recording lessons. One tablet is used as a weapon; another hangs on the wall. The same goes for satchels. A couple of students wear a pen case and ink pot on their belts; others hang on the wall.

Artists used marginal areas of a work of art to depict unusual ideas about a variety of topics, including education. A misbehaving monkey is whipped by his monkey tutor while two other monkeys look on, one with a sheet of paper or parchment on its lap (Illus. 7). A tutor holds withes in one hand and a tablet with the other while a grinning dog writes on the tablet, a stylus gripped in its right forepaw (Illus. 8). Above them are the letters ABC. Finally, a fox wearing a scholar’s cap, raising a baton with his right forepaw, teaches a flock of geese the art of singing. They all stand at a lectern with a book open perhaps to the text they are to sing (Illus. 9).

Illustrations:

Observing the passing of time was central in medieval society, since climate had a profound effect on one’s livelihood and life habits. The turn of the seasons brought changes in diet, hygiene, mood, and activity, which were detailed and collected in a genre of late medieval health handbook known as Tacuinum Sanitatis (“The Maintenance of Health”). These show that, in preparing treatments, doctors took the time of the year, month and even day into account, along with six ‘non-natural’ factors—air, food and drink, motion and rest, sleep and waking, secretion and excretion, and mental state—as well as bathing (Jones 119; 133). Such factors are reflected in the Psalter of Lambert le Bèque, which includes twelve medallions forming a health calendar with rules and advice for each month and an image of a doctor with his assistants at the bottom of the page.

While elements of the illustrations were drawn from classical tradition, the medical recommendations and notion of time in the Tacuinum Sanitatis were heavily influenced by similar health handbooks in Arabic, the lingua franca of the Islamic world. The Tacuinum Sanitatis was based on an Arabic text written by Ibn Butlan, an eleventh-century Christian physician from Baghdad, who is credited as a source in manuscripts from Vienna, Paris, Casanatense, and Liège. His work was so respected by European translators that they even copied out mistakes made by previous Arabic copyists without change. Its translation into Latin in southern Italy or Sicily helped to disseminate it across Europe (Arano 8–11). The work’s Arabic origins are reflected in the title Tacuinum, which comes from the Arabic taqwim, meaning “table” and referring to the table-like organization of health handbooks in the Arabic tradition, a configuration possibly referenced in the square shape of the illustrations in the Tacuinum Sanitatis.

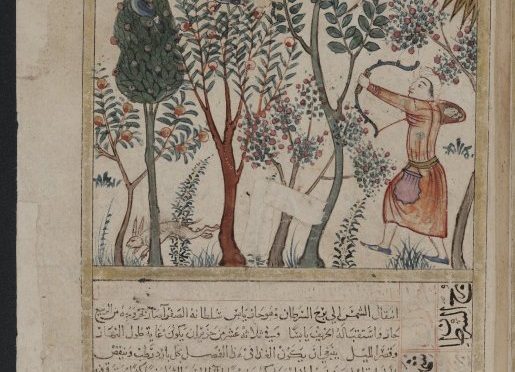

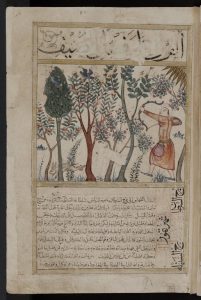

A sense of the Arabic source for the Tacuinum Sanitatis can be found in the Kitab al-Bulhān, a fifteenth-century miscellany in Arabic, now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (MS. Bodl. Or. 133). The Bodleian manuscript compiled various astrological, astronomical, and divinatory texts. Notably, in its tale for the four seasons, it advised the following diet for the summer months:

“Food should be reduced and drink somewhat increased. Drinks must be well mixed with cold water and snow. Warm, dry medicines and foods must be avoided. Only delicate meat is to be eaten, such as that of black lamb (al-humldn al-suid). There is no harm in eating beef and goat’s meat if prepared with vinegar and celery (karafs). One should not linger in the bath nor should emetics be resorted to frequently.” (Arano color plate XII).

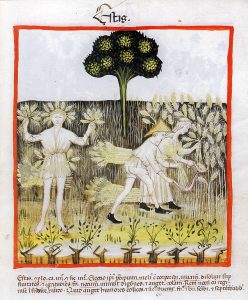

Similar instructions for a humid diet and delicate foods that can be easily digested also appear in a fourteenth-century Latin manuscript of the Tacuinum Sanitatis, written in Lombardy and held in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Cod. Vindob. ser. nov. 2644, fol. 54r). This manuscript states that when nature is “warm in the third degree, dry in the second” the body is at its optimum health to beat “superfluities and cold diseases.”(Arano color plate XII). Yet the summer months were not without their health afflictions, like sluggish digestion or an increase in bilious humors. The Vienna Tacuinum codex suggests taking in a “humid diet” in a “cool environment” to overcome these disagreeable humors. The handbook states that a continuation of the diet works in “cold temperaments, for old people, and in Northern regions.” (Arano color plate XII).

The accompanying image of a youth wearing a crown of grain and holding a sprig is strikingly similar to depictions of the labors of the month and the personification of summer.

This imagery found its way into other media recorded by the Index, such as a Veronese fresco fragment in the Museo Civico di Castelvecchio in Verona. Dated to the last quarter of the fourteenth century, this fresco contains three scenes from the Tacuinum Sanitas. Fragments from the Palazzo dei Tribunali in Verona depict occupational scenes of cooking and commerce that address the inclusion of starch and dill in the diet.

Interestingly, once the Tacuinum text became popular in Europe, Italian innovations began making their way back into Arabic manuscripts. The illumination in the Lombardy manuscript was also influential in the development of contemporary landscape painting, focusing on the changes in nature itself, as well as human responses to them. This influence is perceptible in the Bodleian manuscript, made approximately a decade after the Italian manuscript. The illumination of seasons and cycles here shows a distinctly European approach with Arabic elements worked in. These details include turbaned figures in rich pastoral landscapes dotted with European architecture, a hunter’s long, pointed shoes, a half-length traditional gown, a belted pouch and a goblet of wine in the Autumn scene. And so the artist of the Bodleian Kitab al-Bulhān blended elements of both cultures with innovations of his own, according to his taste.

The Index catalogs many images of seasonal and medical imagery, including “Scene, Occupational: Doctoring” (60+ work of art records) and “Scene, Occupational: Cooking” (70+ work of art records).

Sources:

Ann Henisch, Bridget. The Medieval Calendar Year. (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1999)

Carson Webster, James.The Labors of the Months in Antique and Medieval Art to the End of the Twelfth Century. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1938)

Cogliati Arano, Luisa. Medieval Health Handbook: Tacuinum Sanitatis. (New York: George Brazilier, 1976)

Hourihane, Colum, ed. Time in the Medieval World: Occupations of the Months and Signs of the Zodiac in the Index of Christian Art. (Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2007)

Murray Jones, Peter. Medieval Medical Manuscripts. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984)

Rice, D. S. ‘The Seasons and the Labors of the Months in Islamic Art’. Ars Orientalis 1 (1954): 1-39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4628981.pdf

This guest blog post was written by Rachel Dutaud, a summer student assistant at the Index of Christian Art and a fourth year art history student at the University of St. Andrews. Rachel is completing her undergraduate dissertation on the portraiture of Hatshepsut, Olympias of Macedonia, and Theodora. Her interests are in Early Christian and Byzantine art, classicism, iconography, and archives.

The Index of Christian Art is sponsoring two sessions in honor of Adelaide Bennett Hagens at the 52nd International Congress on Medieval Studies, University of Western Michigan, Kalamazoo, MI, May 11-14, 2017.

Image & Meaning in Medieval Manuscripts: Sessions in Honor of Adelaide Bennett Hagens

Session I: Text-Image Dynamics in Medieval Manuscripts

Session II: Signs of Patronage in Medieval Manuscripts

Organizers: Judith Golden and Jessica Savage, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Please see the full call for papers on our website here: https://ima.princeton.edu/conferences/

The Index of Christian Art presents three images in honor of the 160,000 allied troops who landed on the fortified beaches of Normandy on 6 June 1944. The first, a detail of the Bayeux Embroidery portraying Duke William of Normandy sailing to England, evokes the seaborne operation that marked the beginning of the liberation of occupied Europe from Nazi control. The second, a sculpted personification of Fortitude holding a sword and shield from the west façade of Notre-Dame of Paris, speaks to the courage and resilience of the allied forces in the face of the enemy. The third, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s languid depiction of Peace from the Allegory of Good Government fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, alludes to the aftermath of the war, while also expressing hope for the resolution of current conflicts worldwide.

Mother’s Day has been celebrated annually in the United States on the second Sunday in May for over one hundred years. Following its declaration as an official holiday by the state of West Virginia, Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation announcing the first national Mother’s Day on 9 May 1914.

Images of the Virgin and Child are among the most common depictions of motherhood from the Middle Ages. The Strahov Madonna of ca. 1340 captures the dynamism (or “squirminess”) typical of small children, while also communicating to beholders the special status of the figures through solemn expressions and meaningful gestures. The Child grasps his mother’s veil with his left hand and holds a goldfinch in his right hand, a pose adapted from the Virgin Kykkotissa, a highly venerated, miracle-working Byzantine icon thought to have been painted from life by Saint Luke. Portrayals of the Visitation present an earlier stage of motherhood.

A fifteenth-century French Book of Hours shows the pregnant Virgin gently cradling her swollen abdomen as she greets her cousin Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist, who “leaped in her womb” (Luke 1:41). A thirteenth-century fresco of the birth of John the Baptist from Parma Baptistery captures yet another aspect of motherhood, depicting two midwives tending to Elizabeth as two others bathe her newborn infant.

The Index of Christian Art has 29 subject records for the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. John the Baptist: Birth appears in 104 records.

The middle of April strikes dread (or joy) in the hearts of millions of tax filers. Since 1955, April 15 has typically marked the end of the tax season in the continental US. This year, however, filers have received a three-day reprieve to accommodate Emancipation Day in Washington D.C, which is observed on the weekday closest to April 16 when it falls on a weekend.

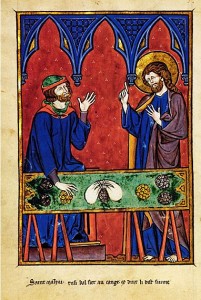

Saint Matthew is among the best-known tax collectors in the history of Christian art. According to the gospel accounts, Jesus encountered Levi (Matthew’s name before his conversion) in the custom house of Capernaum on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. Jesus said to him, “Follow me,” and Matthew obeyed.

A remarkable depiction of Christ calling Matthew appears in the Picture Book of Madame Marie, a thirteenth–century French devotional manuscript now at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. The scene takes place beneath sharply-cusped arches and against a fiery background. Wearing a brilliant blue garment and purple cloak, Christ addresses Matthew, whose money table has been dramatically tilted to reveal neat piles of gold and silver coins. Thematically related is a fifth-century gold solidus of Pulcheria with the empress wearing an elaborate coiffure and lavish jewels, a macabre Dance of Death featuring a money-changer from a fifteenth century French Book of Hours, and a regal image of the Queen of Coins on a fifteenth-century Italian tarot card.

May the rocks in your field turn to gold!

“And when he was come into Jerusalem, the whole city was moved, saying: Who is this? And the people said: This is Jesus the prophet, from Nazareth of Galilee.” (Matthew 21:10-11)

Celebrated seven days before Easter Sunday, Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Passion Week and commemorates Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The episode, which appears in the four canonical gospels, describes the multitudes gathering at the gates of Jerusalem to welcome Jesus, laying their cloaks and branches on the ground in recognition of his status as the Messiah.

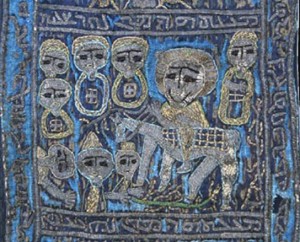

The earliest extant pictorial representations of the Entry into Jerusalem date to the fourth century, and the subject was popular across media throughout the Middle Ages. A highly compressed version of the episode appears on a fourteenth-century ivory diptych from the Abbey of Muri, Switzerland, which is decorated with Passion scenes. The right side of one of the leaves portrays a single disciple trailing the mounted Christ blessing two figures, who serve as shorthand for the multitudes. Equally schematic is the Entry into Jerusalem on the batrashil of bishop Athanasius Abraham Yaghmur of Nebek, produced in Syria in the fourteenth century. This long, embroidered stole shows three figures placing a palm branch before Christ, riding on an ass and attended by five disciples.

The lintel from the main portal of the twelfth-century church of San Leonardo al Frigido in Italy presents a more expansive version of the scene by illustrating all twelve disciples, their open mouths perhaps indicative of speech, and three small figures perched in a tree on the right-hand side of the composition. The last detail, common in depictions of the subject, relates to the prophecy of Zechariah, which describes children breaking branches from an olive tree and following the crowd into Jerusalem.

This year, the vernal equinox in the northern hemisphere falls on Sunday, March 20, marking the moment when the sun shines directly on the equator and the length of day and night are nearly equal. In anticipation of the change of season, The Index of Christian Art presents images thematically related to spring. First, a fifth-century mosaic from the synagogue in Zippori, an abandoned Roman-era town in central Galilee, depicts a personification of spring, identified by Greek and Hebrew inscriptions. Portrayed with roses in her hair, the bust-length figure is flanked by a blossoming branch and a bowl of flowers (on the left) and a basket of flowers and two lilies (on the right).

Second, a personification of March, labelled MARCIUS, graces a Catalonian textile from the late-eleventh or early-twelfth century. The figure appears to be chasing a stork (CICONIA), known as a harbinger of spring because of its migratory patterns. The figure holds a serpent, described in medieval bestiaries as an enemy of the stork, and a frog, perhaps a reference to the rainy season. Above is a personification of the north wind (FRIGUS), as well as a crescent moon and blazing sun. Last, a thirteenth-century Flemish Psalter depicts a figure pruning a stylized tree, an agricultural labor closely associated with the month of March.

Celebrated annually on February 14 as a day for courtship and romance, Valentine’s Day began as a liturgical celebration in honor of one or more Early Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The Roman Martyrology mentions two Valentines, both of whom were decapitated on the ancient Via Flaminia, the main artery connecting the city of Rome to the Adriatic Sea. One Valentine died in Rome and seems to have been a priest. The other, who may have been a bishop, was martyred approximately 60 miles away at Interamna (modern Terni).

The earliest extant connection between Valentine’s Day and romantic love appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (1383): “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.” February 14 was associated with courtly love as early as 1400, in a charter ostensibly issued by Charles VI of France (d. 1422). The text describes the festivities of the royal court, which included love poetry competitions, dancing, jousting, and a feast. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm evidence linking Valentine’s Day with the ancient Roman Lupercalia, a pastoral festival observed from February 13 through 15 to purify the city of Rome and to promote health and fertility.

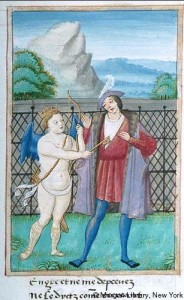

The Index of Christian Art is delighted to present four images thematically associated with Valentine’s Day. First, the nimbed Valentine of Rome is represented with the sword of his martyrdom in the fifteenth-century Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Morgan Library, M.917 and M.945). Second, a sixteenth-century Roman de la Rose contains a charming depiction of the God of Love locking the Lover’s heart with a giant key (Morgan Library, M.948). Third, a fourteenth-century ivory box cover of Parisian origin shows women defending the castle of love, a popular subject in late medieval courtly circles. The winged god of love at the top of the roundel prepares to launch his arrow, while women throw flowers at the attacking knights. Last, a sixteenth-century drawing from an Arma Christi and Prayers (Princeton University Library, Taylor 17), which portrays Christ’s heart with three blossoming flowers, is inscribed pyte, love, and charyte.