Are you familiar with the popular iconography of the saint whose feast day falls on April 23? If you’ve ever been to an English pub, you probably are, even if you didn’t realize it! According to medieval legend, Saint George of Cappadocia was the third-century saint and martyr who slew a dragon. Usually, George is represented as a knight mounted on a horse. Sometimes shown carrying a cross-inscribed shield, his red and white armorial attribute, he thrusts his lance into the jaws of the dragon under his horse’s hooves.

George’s heroic posture was modeled on the iconography of other saints and mythological figures. Theodore Tyro and Demetrius of Thessalonica, for example, also slew beasts in the name of vanquishing evil. Carrying talismanic or protective power for people threatened by worldly dangers, dragon-slayer images decorated many small, portable objects, including ampullae, lamps, carved gems and small plaques from the late antique, Byzantine, and Coptic worlds.1 Building on narratives of his heroism, tales of George’s life and deeds spread throughout medieval Europe with Crusaders returning from the East. By the high Middle Ages, the Golden Legend, a compilation of saints’ lives by Jacobus de Voragine, fleshed out the life of George with a rescue narrative of a king’s daughter and inspired numerous visual representations in different media.2

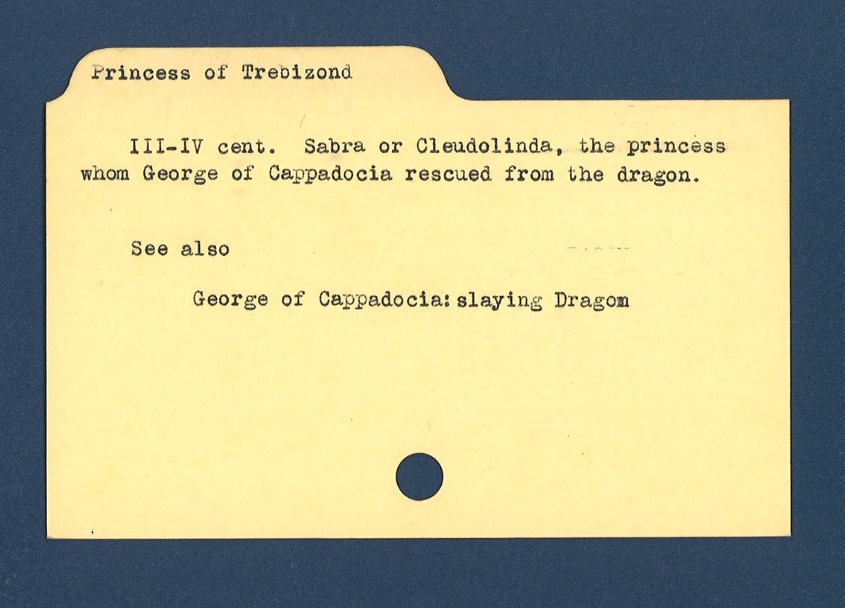

Depictions of the rescue legend, which follow standard iconography for George’s slaying of the dragon, often insert the princess as a minor character of relative insignificance. But is she insignificant? Traditionally identified as a third or fourth century Komnenian princess of Trebizond, she is sometimes named Sabra or Cleodolinda (or Cleolinda, Cleudolinda) (Fig. 1). According to the legend, the princess was weeping profusely, anticipating her certain death as the next human sacrifice to the dragon, when George arrived at a town called Silene in Libya. He pledged to help her, and he rode toward the dragon with his sword drawn.3 In swift succession, George pierced the dragon and the princess bound her girdle around the beast’s neck. She led it back to the townspeople alive which brought about the people’s mass conversion to Christianity.

In some earlier depictions of the legend, the princess appears with prominence, including on a Romanesque capital from a monastery in Saint-Pons-de-Thomières now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the capital face, the princess wears a long dress, props one hand on her hip, and extends a flower toward George (Fig. 2). Around the other side, George kneels behind his shield, trailing a coiled serpent that approaches the princess from behind. Her thank offering to George in the midst of his attack on the dragon suggests that there will be a good outcome despite the violence surrounding her.

In another Romanesque capital from the abbey of Saint-Pierre of Airvault in Poitou, the princess stands behind George, although he rides away from her, effectively separating her from the dragon’s reach (Fig. 3). With George exiting left, the princess becomes a key figure of interest to viewers gazing upward at the capital. Here, she maintains a stoic stance, and, in ironic juxtaposition with the nearby head of a menacing grotesque, her arms are crossed over her body in a way that suggests patience and perseverance in the face of danger.

By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the iconography of the princess and her role in George’s slaying of the dragon were handled with more flexibility, especially in manuscript illumination.5 Some examples, such as the Hungarian Angevin Legendary, illustrate the narrative more literally, showing the princess tethering the dragon or leading it away by its makeshift leash (Fig. 4). In this variant of her iconography, the Princess of Trebizond is actively engaged with George’s feat and secures the dragon in one forceful pull.

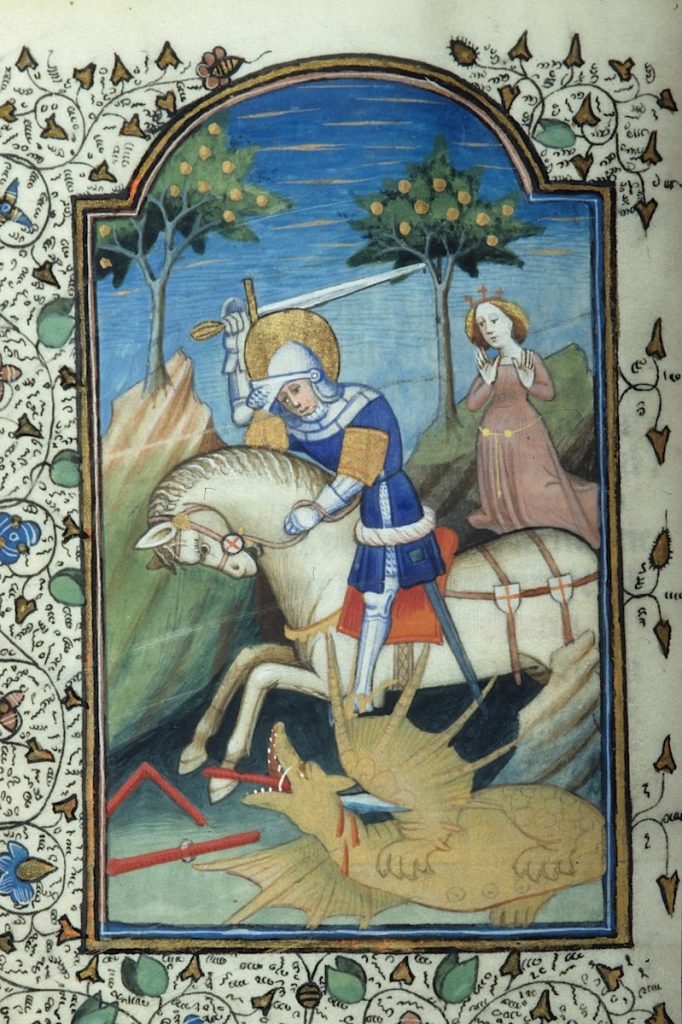

At George’s suffrage in illuminated prayerbooks, especially in Books of Hours, the princess often appears behind the slaying scene, kneeling in prayer, and protected a distance.6 But in some of these late medieval depictions, she tends a flock of sheep, sometimes holding one sheep on a lead, or she simply raises her hands in surprise at George’s victory (Fig. 5).7

In all these images, the princess functions as more than a mere attribute of George. Instead, she is actively reimagined as part of the narrative. Artists creatively customized their images of Georgian legend to not only explore the princess’s instrumental role in her rescue but to highlight her intercessory function in saving the townspeople–in a literal sense and by their newfound faith. Whether showing her as prayerful, gracious, surprised, or tethering the dragon, the iconography of the princess offers a versatile model of female agency, one that likely inspired her viewers.

We can find echoes of such rescue narratives in other ages and media. If you have played the classic Super Mario Bros. video game, then you know the game’s mission: rescue Princess Peach! As aficionados know, the eighth and final world of the game culminated in an underground battle with Bowser, the hammer-hurling, spiky-shelled antagonist (Fig. 6). If you hurled enough fireballs back at Bowser, he overturned and descended into an abyss off screen, allowing Mario to advance over the bridge and reach the princess on the other side. Much like the Princess of Trebizond, Princess Peach had to be rescued, and she, too, has been reimagined over time: her characterization within the Nintendo empire of games and films eventually evolved from damsel in a dungeon to a fighter in her own right.8

You can still find the iconography of George slaying the dragon in the modern world, often in a reduced composition of equestrian, saint, and dragon. Once you know what you’re looking for, you’ll spot George in any number of settings, especially on pub signs like the one on my local haunt when I was a grad student in London (Fig. 7). Whether under his sign or not, those who cheer to Saint George today would do well to remember this: once upon a time, a princess filled with purposeful character also conquered a beast.

Thank You, Saint George! Your Quest is Over.

Appendix

The Index subject files provide a starting point to locate examples of the Princess of Trebizond in the six works of art:

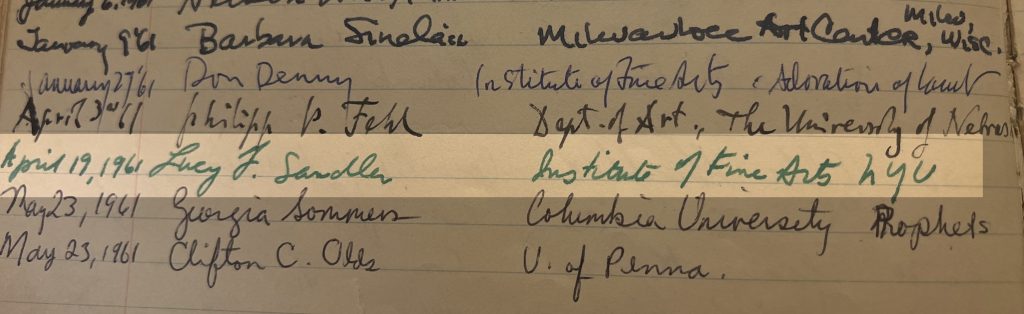

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to continue a series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by hundreds of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections and warmly thank Lucy Freeman Sandler, Professor Emerita, Institute of Fine Arts of New York University, and Index friend for her time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I began to study painting at Queens College but my first undergraduate art history course focused my interest in a new direction, and, inspired by a charismatic medievalist, Frances Godwin, I decided to study the art of the Middle Ages on the graduate level. On Prof. Godwin’s advice I applied to and was accepted at Columbia University and took courses with Meyer Schapiro, a formative intellectual experience, and then with John Plummer, who was then himself completing a Ph.D. with Schapiro. It was Plummer’s course, called “Gothic Painting,” which was primarily about illuminated manuscripts, in which I “discovered” marginal illustrations, a topic that became the subject of my master’s thesis. For my own Ph.D. I transferred to the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University (they generously awarded me a scholarship), eventually completing a dissertation on the Psalter of Robert de Lisle (London, British Library, Arundel MS 83).

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

I cannot remember the date of my first visit to the Index, which Index records indicate was 1961, during the time I was working on my dissertation. I have certainly used the Index many times since, and have known all its directors since Rosalie Green, although, to my regret, I did not meet her.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

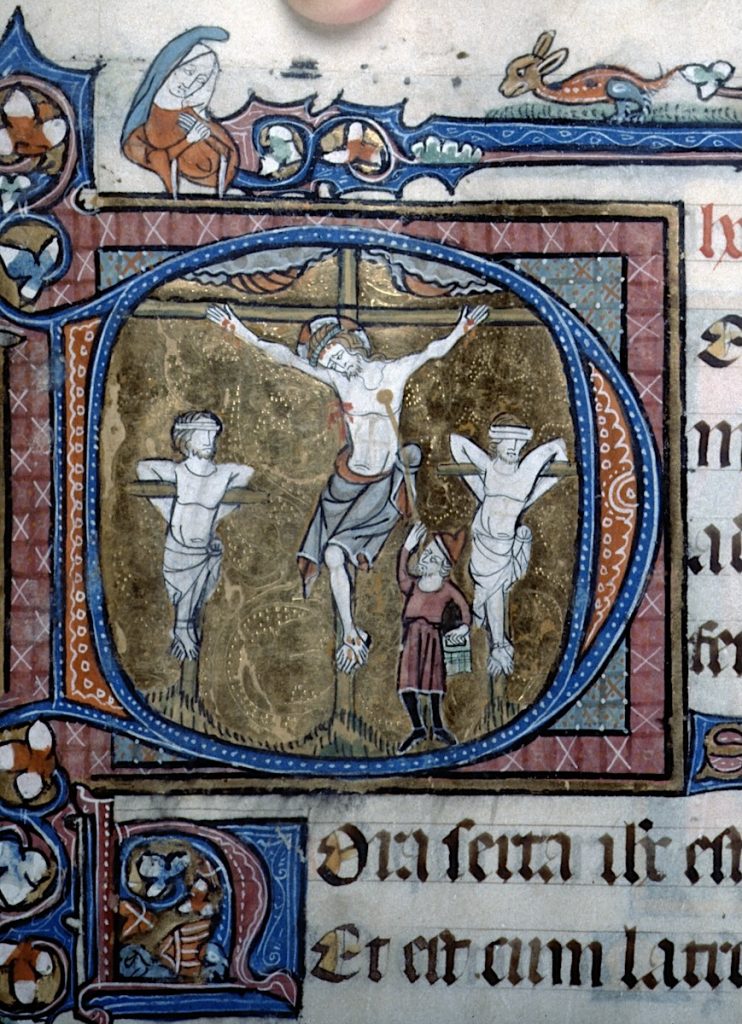

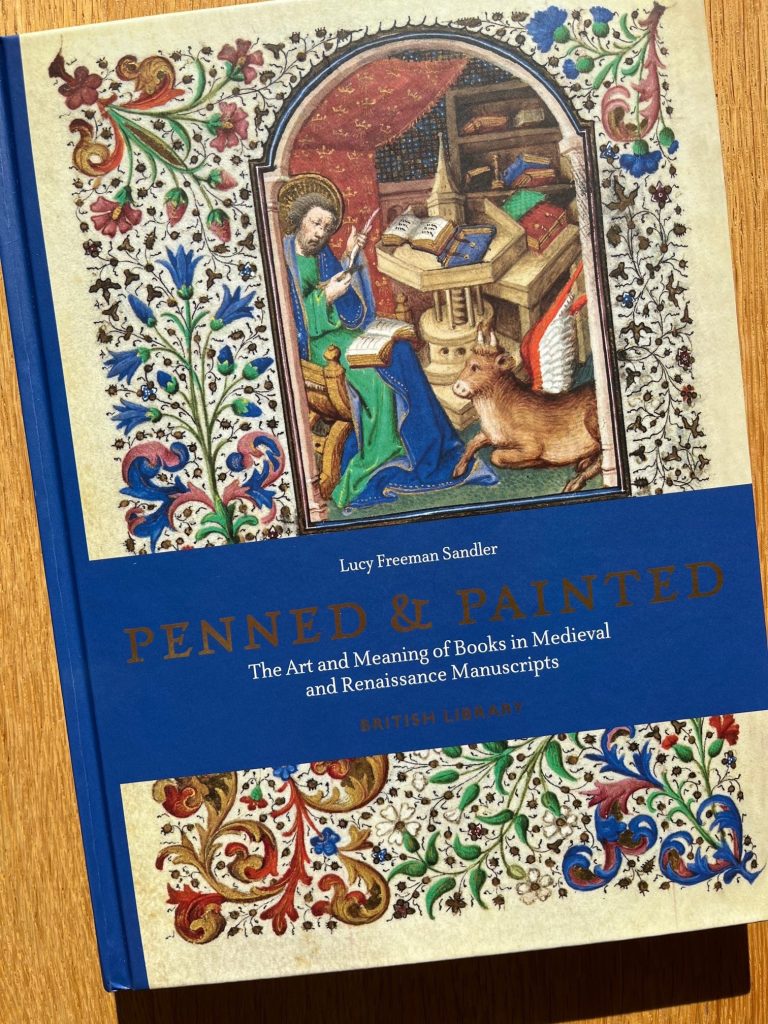

I remember at least one visit, probably sometime between 1961 and 1964, when I was trying to determine the date during the Gothic period at which the crossed feet of the Crucified Christ changed position. I must have looked at hundreds of photos of every late thirteenth and fourteenth century Crucifixion at the Index. I can’t say that I came to any definitive conclusion but I certainly learned a lot about Crucifixion representations. I have found the online version of the Index invaluable, especially in connection with my latest book, Penned & Painted: The Art and Meaning of Books in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts (London: British Library, 2022), for which I did much of the research during Covid.

Have you attended or presented at an Index conference? Which conferences were particularly memorable or helpful to your work?

I have attended quite a few Index conferences and have spoken at several, including “The Weingarten Office Lectionary and Passionale in New York and St. Petersburg,” in Romanesque Art and Thought in the Twelfth Century in Honor of Walter Cahn (October 2006); “One Hundred and Fifty Years of Study of the Illuminated Book in England: The Bohun Manuscripts from the Nineteenth Century to the Present,” in Gothic Art & Thought in the Middle Ages: A Conference in Honor of Willibald Sauerländer (March 2009); “The Bohun Women and Manuscript Patronage in Fourteenth Century England,” in Medieval Patronage: Patronage, Power and Agency in Medieval Art (October 2012); and “Princeton Garrett MS 35 and Homeless English Gothic Manuscripts,” in Manuscripta Illuminata: Approaches to Understanding Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts (October 2013). All these were subsequently published under the editorship of Colum Hourihane. I also contributed a tribute to John Plummer: “John Plummer: A Reminiscence,” in Between the Picture and the Word: Manuscript Studies from the Index of Christian Art, ed. C. Hourihane (University Park, PA, 2005), 9–11.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the field of medieval iconographic studies over the last three decades?

As co-editor of the Index-based Studies in Iconography, from 2009–2015, I hoped to serve the mission of the journal, as it has continued to the present, to publish “innovative work on the meaning of images from the medieval world broadly construed.”

Thank you, Lucy! As the home for Studies in Iconography we’re committed to publishing innovative work in iconographic studies, and we’re grateful for your invaluable contributions to the Index over so many years.

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2025.

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to introduce a new AI assistant to support users in their research on medieval iconography. The new IAI (Index Artificial Intelligence) aims to save researchers time and energy by aggregating search results into a digestible single image for use in your research paper or article. No more online filters to manipulate, index drawers to pull out, or search results to sort: simply tell IAI what you’re looking for and it will deliver an image that distills all the essential features of your search terms into the quintessential example for your next research project. And because it’s AI generated, no one will worry about copyright permissions.

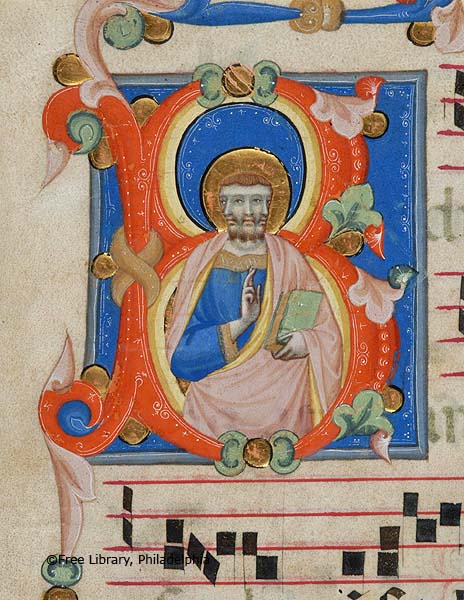

Perhaps you’re looking for a traditional inhabited initial in a musical manuscript, say a representation of the blessing Christ inhabiting the initial B of “Benedictus.” You could of course search for existing images in the traditional way, using the Subject term “Christ, Blessing” or an Associated Text using an incipit like “BENEDICTA SIT….” That could yield a lot of search results! But who wants to comb through those? Let IAI do the job for you, and you could get something like this:

Here, nested cozily in a bright vermilion letter B with all the right kinds of leafy decoration, is a generously robed figure of Christ holding a book as he raises his hand in blessing. Is it perfect? Well… you know how sometimes figures in AI art come out with a couple of extra fingers, or arms, or maybe even faces? Let’s just say we’re still working out a few things.

In the meantime, maybe you’re interested in legendary beasts and looking for a medieval depiction of a fierce mythological animal, say one that uses massive horns and fire to defend itself from attackers. IAI has got you covered! Of course, you could dig around in the Subject Classifications network to see all the different kinds of animals you can actually find in the Index of Medieval Art, maybe checking out the “Mythological and Religious Creatures” category to find your fiery friend. But searching on your own is so old school. Let IAI do it for you! We know you’ll like what you see.

Big horns: check! Fire: check! Attackers repelled: check! Oh wait, you wanted the fire coming from its mouth? How was IAI supposed to know that? Maybe you should have searched on your own for this one, using the Subject term “Dragon.”

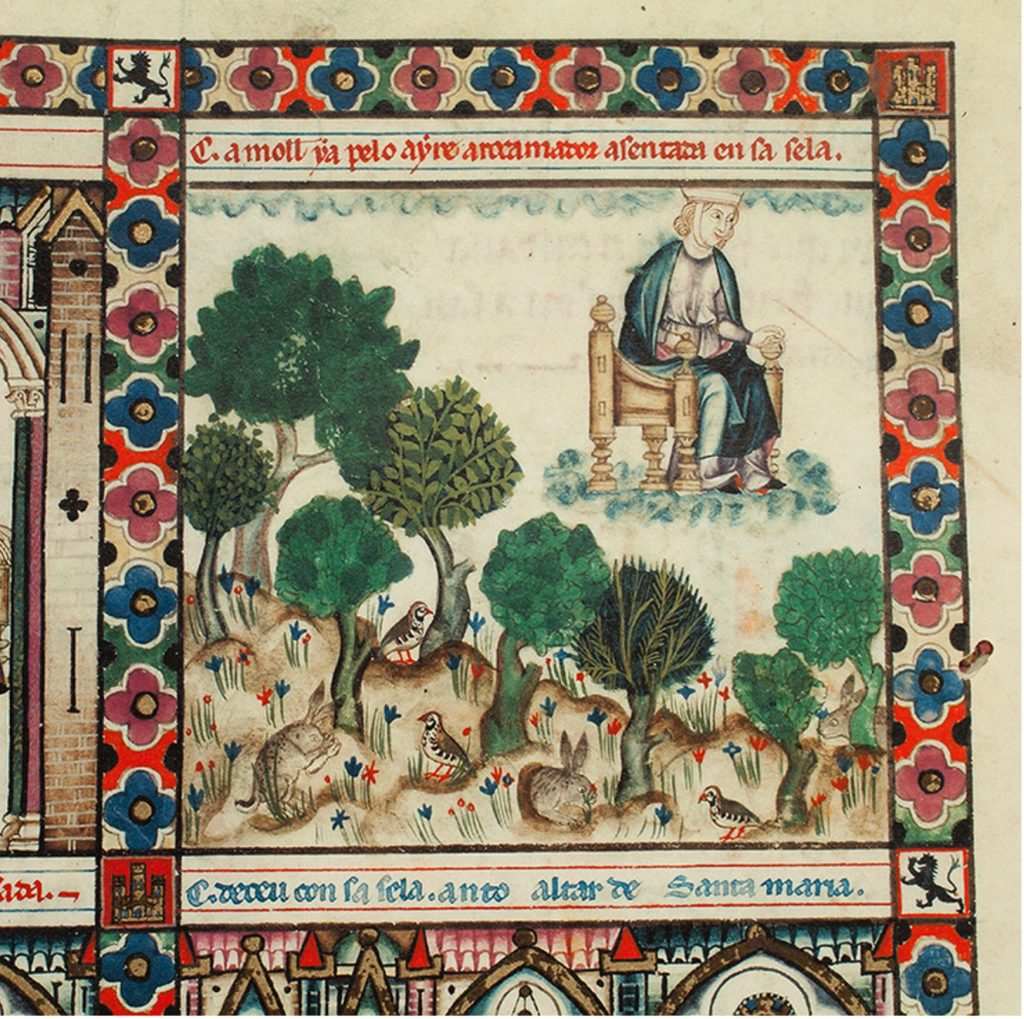

Let’s try something a little simpler. How about a medieval pilgrim? Pilgrimage to sacred sites, whether for penitence or to show devotion, was so important to medieval people that you won’t be surprised to learn there are more than thirty Index Subjects starting with “Pilgrim” in the database. But do you really want to take the time to look at all of those and then have to make decisions about which ones best suit your research needs? IAI has got your back. Let’s make it authentic by narrowing the parameters: we’ll ask for a female pilgrim on her way to the shrine of Our Lady of Rocamadour.

That’s a lady pilgrim all right, and the captions tells you she’s definitely on the way to Rocamadour. Yes, it does seem a little unusual that she’s flying there in a chair instead of riding a donkey, but of course if you’d wanted that kind of detail, you would have used the search filters for a Boolean search of the Subjects “Pilgrim” and “Donkey.” But since when were donkeys so important? IAI thinks this is a terrific way to go. You’ve never heard of armchair travel?

Even if IAI still has a kink or two to work out, we think you’ll love what it can do for you. Mental energy is precious; why devote so much of it to original image research when you can harness multiple terabytes of data and enough electricity per search to fully charge your phone just so IAI can come up with one fantastic image like these? Is IAI easy? You bet. Is IAI fun? Tell us, who doesn’t love flying chairs and flaming poo? Is IAI responsible? Now why would you ask us that? It’s not a self-driving car.