Matthew’s Gospel tells us that, at the moment Christ died, darkness swept over the land for three hours (Matthew 27:45). The foreboding skies at Christ’s crucifixion were also recorded in Luke 23:44-45 and Mark 15:33. Mark’s account, thought to have been written around the year 70 CE, was likely the earliest.[1] Some scholars have reasoned that this midday phenomenon was an actual eclipse, because the passage in Luke reports that darkness fell over the land when “the sun was eclipsed” (“τοῦ ἡλίου ἐκλιπόντος”) (Luke 23:45). However, the passage is usually translated “the sun was darkened.” The verb is in the passive voice, as is the verb “ἐσκοτίσθη” used in other versions of the Greek text, and both words can mean “was darkened” or “was obscured.”[2] No matter how we may interpret the words relating the phenomenon, and no matter whether it is possible to attribute the darkness thus described to a real astronomical event, scriptural hours of daytime darkness over Golgotha presented an iconographic opportunity to medieval artists depicting the Crucifixion.

In manuscripts and painted works of art that aimed to depict the event, color was frequently exploited to illustrate darkness and to create a dramatic setting. Across media, the celestial bodies of the sun and the moon were incorporated into the skies above the crucifixion, not only to signal darkness at daytime but also to imbue the scenes with a rich cosmological significance.

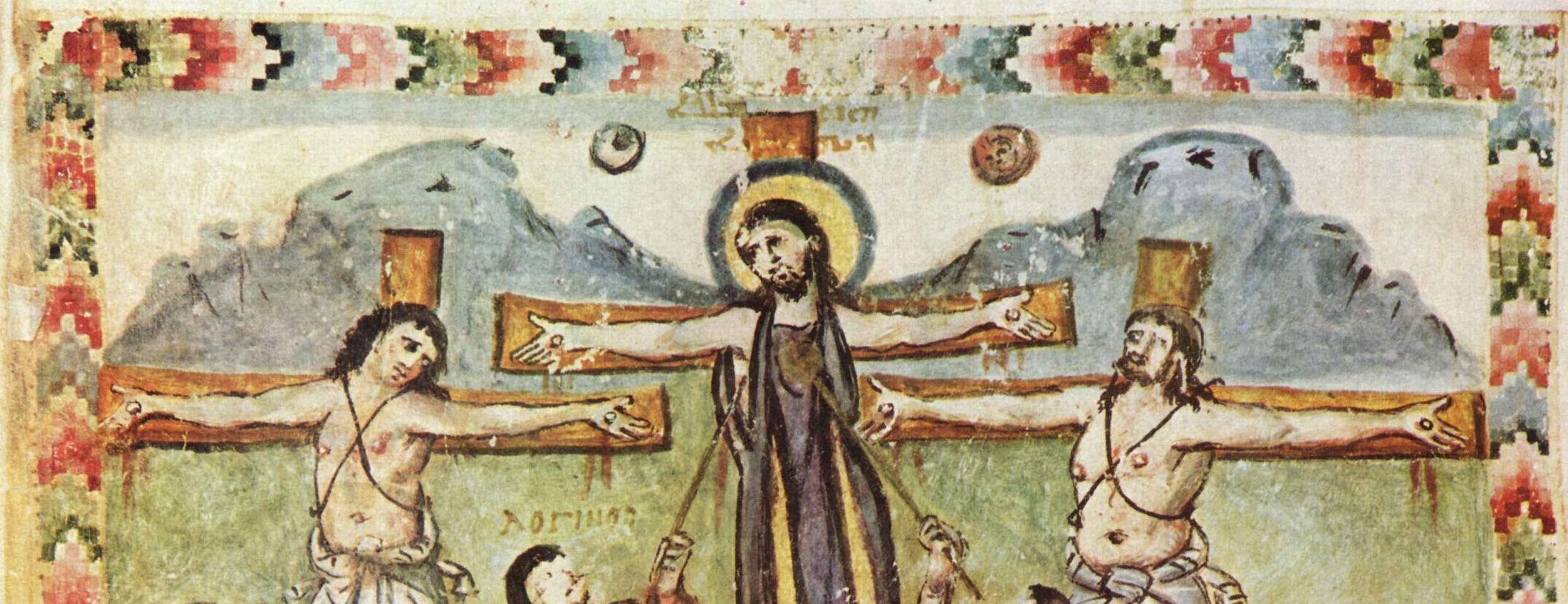

An especially early example appears in the Syriac Rabbula Gospels from the late sixth century. In this manuscript, the Crucifixion includes a partly eclipsed Sun and a Moon with a face against a remarkably light sky; a sliver of shaded pigment at the top suggests darkness (Figure 1). From antiquity, the sun and moon were associated with power. In early medieval crucifixion scenes they represented God’s cosmic anger at the death of Christ.[3] Throughout the Middle Ages, personifications of the Sun and Moon became regular characters at the Crucifixion, positioned as sorrowful figures mourning Christ’s death. The placement of the Sun and Moon respectively at the right and left arms of the cross came to be read typologically as the Old and New Testaments.[4] After about 850, they could also be seen as allegorical representations of Church and Synagogue.[5]

The Ottonian Sacramentary of Henry II sets the Crucifixion scene against a deep purple background, a striking hue used to set a somber mood and suggest darkness (Figure 2). Busts of the personifications Sun and Moon sit on the arms of the cross. The Sun, labeled SOL and sporting a rayed headpiece, and the veiled Moon, labeled LUNA, both turn away from the scene and weep into their draped hands. The strong background color effectively conveys the darkness of this scene emphasized by the dramatic gestures of the Sun and Moon.

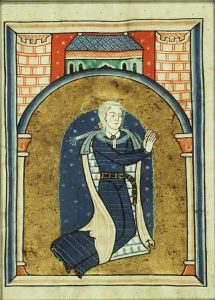

Medieval artists sometimes set the same iconographic features within a flattened space of gold or patterned backgrounds. A leaf from the Potocki Psalter, made in Paris in the mid-13th century, sets the Crucifixion against a gold background (Figure 3). Christ is flanked above by the sun and moon and below by the Virgin Mary and the Evangelist John. Within this composition, the three main figures hover between time and space, darkness suggested only by the presence of the partly obscured sun and the crescent moon.

Similarly, in a Crucifixion scene painted around 1400 to 1410 in a Register of Coiners and Minters from Avignon, a richly patterned background of gold scrolls avoids any illusion of a dim sky (Figure 4). The red sun and the moon’s countenance in the upper corners of the miniature are the only clues that the ornamental ground is actually simulated “darkness.” In both miniatures, decorative and luminous backgrounds highlight the central features of the scene so that the Crucifixion image becomes a place of mediation, the background “darkness” metaphorically positioned between an earthly space and a shift in the cosmos at the moment of Christ’s death.

Images of darkness at the Crucifixion can be found in the Index database by any of several possible search strategies. One method is to perform an advanced search using the keyword “Crucifixion” while filtering with the subject “Sun and Moon.” This search returns over 380 results. Executing the search again with the subject “Personification: Sun and Moon” returns around 220 examples in a variety of media, including ivory plaques, glyptics, and frescoes. “Personification: Sun and Moon” is the subject used by the Index for records concerning works on which both celestial bodies have facial features. Using words like “stars” or “starry,” background elements that can also suggest a dark sky may be recorded in the Index’s descriptions of such works.

With the advent of the Index of Medieval Art’s new database, thumbnail images are now visible with search results, allowing the researcher to review works of art at a glance. Thus, a researcher looking into images of the Crucifixion will be able to notice the gradual change in the later medieval period in the West, when images of the Crucifixion began to represent the three-hour darkness as a true night sky. In a Book of Hours made in Paris about 1490, a soft pattern of gold stars with the sun and moon dot a dark blue sky to create the illusion of evening (Figure 5). Other Crucifixion scenes that a researcher may notice while thumbnail browsing show cloudy, dark, and emotive skies that convey darkness without the sun or moon. These atmospheric scenes offer a remarkable and naturalistic, if not peaceful, departure from the earlier ones with their grief-stricken personifications of the Sun and Moon.

The starry night sky casts a familiar source of light over a recognizable scene, and these astronomical bodies inspired fascination in medieval minds still forming theories about what those bodies might actually be. Nevertheless, the symbols of the Sun and Moon, while signaling darkness and the passage of time, also imparted emotional weight, persisting in iconography not only to adhere to scriptural tradition, but also to emphasize the significance of Christ’s death.

Further Reading

Hautecoeur, Louis. “Soleil et la lune dans les crucifixions.” Revue archéologique, ser. 5, XIV (1921): 13-32

Schiller, Gertrude. “The Crucifixion.” In vol. 2 of Iconography of Christian Art, 88–164. London: Lund Humphries, 1972.

Nickel, Helmut. “The Sun, the Moon, and an Eclipse: Observations on The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, by Hendrick Ter Brugghen.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 42 (2007): 121–24.

[1] The Gospels report three other supernatural events that occurred during the Crucifixion: the temple veil was split in two; various earthquakes shook the land; and the souls of the dead rose from their graves. See related subjects in the Index of Medieval Art: Christ: Crucifixion, Earthquake; Christ: Crucifixion, Resurrection of Dead, and Veil of Temple: rending.

[2] Bible Translation. “David Robert Palmer trans., The Gospel of Luke: Part of The Holy Bible.” Accessed 30 March 2018. Bibletranslation.ws/trans/lukewgrk.pdf. See especially p. 116, n. 307.

[3] Gertrude Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, trans. Janet Seligman (London: Lund Humphries, 1972), 2:94.

[4] This interpretation was promoted by St. Augustine (354–430 CE). Schiller, 109.

[5] Schiller, 110.

The Index is pleased to announce the speakers for two honorary sessions at the International Congress on Medieval Studies to be held at Western Michigan University (Kalamazoo, MI) on May 11-14, 2017.

Organized by Judith Golden and Jessica Savage, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Presider: Judith H. Oliver, Colgate University, Professor Emerita

This session will examine the interaction between words and images in medieval manuscripts as they shape the reader-viewer’s experience of the book. How do texts and images interact on the page? How did medieval readers respond to the varied discourses between images and texts? This session endeavors to open up new perspectives in describing, analyzing, and contextualizing manuscript illumination according to their intrinsic or peripheral textual elements. Papers in this session will undertake a close study of a particular manuscript and will expand upon theories for image-text composition by reviewing evidence of an artist’s written instructions; reading images with layered text additions, omissions or annotations; and recovering the reader’s experience through text and iconography.

“Artists and Autonomy: Written Instructions and Preliminary Drawings for the Illuminator in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea (HM 3027)”

“Bodies of Words: Text and Image in an Illustrated Anatomical Codex (Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 399)”

“A Votive ‘Closing’ in the Claricia Psalter (Walters MS W.26)”

Presider: M. Alison Stones, University of Pittsburgh, Professor Emerita

This session will examine the varied “visual signatures” of manuscript patrons, including dress, gestures, posture, and attributes of donor figures; heraldry and personalized inscriptions; marginal notes, colophons, dedications, and other signs of ownership and use in medieval manuscripts. Building on scholarship presented in the 2013 Index of Christian Art conference Patronage: Power and Agency in Medieval Art, this session will investigate the dynamic system of patronage centered on the interaction of owners with their books (whether as creator, patron, commissioner, or reader-viewer). Papers will address the importance of gender and social roles in book production, use, and readership, or will expand upon the role of patron as instigator in the book creation process, from payment to design.

“How Owner Portraits Work”

“The Patroness Portrait of the Fécamp Psalter (c. 1180): An Unknown Example of Royal Artistic Commission in Angevin Normandy”

“Patron Portrait as Creation Myth: On ‘Production Scenes’ in Illuminated Manuscripts”

In July 2016, Adelaide Bennett Hagens retired from the Index of Christian Art at Princeton University after fifty years of dedicated research and scholarship. She studied under Robert Branner at Columbia University and joined the Index during the directorship of Rosalie Green. Adelaide has studied medieval art in a variety of media, but her passion at the Index and in her personal research has always been manuscript illumination, particularly of the Gothic period. Her publications include “Some Perspectives on the Origins of Books of Hours in France in the Thirteenth Century,” in Books of Hours Reconsidered, edited by Sandra Hindman and James H. Marrow (2013); “Making Literate Lay Women Visible: Text and Image in French and Flemish Books of Hours, 1220–1320,” in Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces, edited by Elina Gertsman and Jill Stevenson (2012); and “The Windmill Psalter: The Historiated Letter E of Psalm One,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 43 (1980). In two sessions, we celebrate Adelaide’s accomplishments and recognize her contributions to the Index of Christian Art and to the wider medieval and academic community.

The Index of Christian Art is sponsoring two sessions in honor of Adelaide Bennett Hagens at the 52nd International Congress on Medieval Studies, University of Western Michigan, Kalamazoo, MI, May 11-14, 2017.

Image & Meaning in Medieval Manuscripts: Sessions in Honor of Adelaide Bennett Hagens

Session I: Text-Image Dynamics in Medieval Manuscripts

Session II: Signs of Patronage in Medieval Manuscripts

Organizers: Judith Golden and Jessica Savage, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Please see the full call for papers on our website here: https://ima.princeton.edu/conferences/