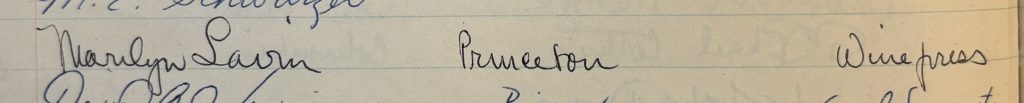

Many people know the name of Belle da Costa Greene, if not also her story as the fledgling librarian who rose to become librarian and then director of the famous Morgan Library & Museum in New York (1905–1948). A major exhibition opening this fall at the Morgan will explore the broad scope of Greene’s life and career, including the challenges she faced as a young woman of African-American heritage who lived as white in a field dominated by powerful European and American men. But where did Greene acquire the training in languages, history, and rare book studies that would advance her career? With the support of the Princeton Histories Fund, a team of researchers from Princeton University Library and the Index of Medieval Art set out to learn more. Their findings include the discovery of Greene’s hand in library records, a letter pinpointing the beginning of her work with the Morgan in summer 1905, and a fascinating correspondence documenting her continuing professional relationship with Princeton faculty and staff after her departure for New York.

These findings will be highlighted in a mini-exhibition opening on November 12, 2024 at Firestone Library and beginning with a round table discussing the project’s findings and their ramifications for Greene’s biography and the history of librarianship. Featured participants will include Kathleen Brennan of Princeton’s Mudd Library; Erica Ciallela of the Morgan Library & Museum and Schlesinger Library, Harvard University; and Mireille Djenno of Firestone Special Collections. The round table will be held at 4:30 pm on Nov. 12 in the Chancellor Green Rotunda, the very building in which the university’s library was housed during Greene’s time at Princeton. It will be followed by a reception and viewing in Firestone Library. Both round table and exhibition, supported by the Princeton Histories Fund, are free and open to the public.

The Index of Medieval Art is delighted to share a call for participation in a field seminar hosted by the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” at the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples on 12-13 June 2025. Associated with the conference “Unruly Iconography?”, which will be hosted on 9 November 2024 at the Index of Medieval Art, “Unruly Iconographies / Iconografie Indisciplinate” will take medieval Naples and southern Italy as a laboratory for exploring relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages.

The seminar organizers welcome proposals that consider individual case studies from medieval Naples and southern Italy as points of departure for investigating questions including so-called exceptions, hapaxes, mistakes, and lost originals; dynamics between “center” and “periphery”; challenges of chronology and dating in so-called peripheries and border zones; circulations of iconographies through polycentric cultural networks; translations of motifs across mediums, formats, functional contexts, and audiences; the legibility and illegibility of iconographies across cultures; mechanisms of transfer including mobile artworks, artists, and patrons; interplays between royal, non-royal elite, and non-elite patronage; and the limitations of previous models of iconography when confronted with cases in medieval Naples and southern Italy. They welcome in particular proposals that locate southern Italy within broader Mediterranean worlds, at the convergence of multiple cultural and religious currents including Latin and Orthodox Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

Further details and a compete call for papers are found here.

The Index of Medieval Art will sponsor the session “Breaking the Mirror: New Approaches to the Study of Medieval Images” at the 60th International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo.

Everyone wants something from medieval images: a sense of story, a corroborated argument, a witness to medieval realities. Although the methods by which scholars seek these answers have evolved considerably, their work remains dominated by the conception of the medieval image as mirror, one that reflects either explicitly or indirectly the truths of the historical past. This session challenges this tendency by asking what we can really expect to learn from medieval images. How does their potential to go beyond illustration—to aspire, deceive, and even fantasize—complicate what and how scholars can learn from them?

We invite papers from researchers at all levels and especially encourage submissions from early-career scholars. The session’s hybrid format can accommodate up to two remote participants. Conference details and a full call for papers can be found at this link.

“Unruly Iconography?” opens a new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules. Its eight speakers will challenge their listeners to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided when iconographic motifs should be considered canonical and which are instead “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” They will interrogate the value and limitations of the unspoken binaries that often underlie such labels: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, or center versus periphery. Their wide-ranging papers will demonstrate the value of a more critically aware, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

“Unruly Iconographies?” will take place on November 9, 2024 and constitutes the first of two internationally linked conferences, the second of which will be a site-based seminar at the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” in Naples in June 2025, which makes southern Italy a laboratory for exploring the relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages.

Speakers for the conference are listed alphabetically below. A schedule and free registration link will be shared on this page in September 2024.

Diliana Angelova (UC Berkeley), “Lawless, Hilarious, Black: Eros and Companions in Byzantium.”

Alexander Brey (Wellesley College), “Iconography Between Empires: The Red Hall at Varakhsha.”

Heidi Gearhart (George Mason University), “A Poem, a Scribe, a Saint, and a Scriptorium: Evoking Multiple Presences in Arras Bibliothèque Municipale MS 860.”

Julie A. Harris (Independent Scholar, Chicago), “Indicate, Illustrate, Decorate, or Comment? Iberian Hebrew Bibles and Their Unruly Paratextual Marks.”

Krisztina Ilko (University of Cambridge), “The Chessmen of the Hunt.”

Nicole C. Paxton (John Cabot University), “Iconographic Innovation and Political Subversion in the Medieval Serbian Akathistos Cycle.”

Patricia Simons (University of Michigan/University of Melbourne), “The Goldfinch: Flights of Fancy.”

Mark H. Summers (University of Arkansas), “Dressed to Impress: Reconsidering Roger II of Sicily and the Iconography of Kingship.”

The Index of Medieval Art is pleased to launch a new series of blog posts that delve into the history of the organization through interviews with senior scholars in the field of art history. The “Guest Book Series” takes its name from the Index guest books, which have been signed by scores of art historians who have consulted the Index files over the past century. We’ve enjoyed reading their recollections, and warmly thank our interviewees for their time and responses.

Please tell us a little about yourself and your work. Where did you study? What inspired you to become a medievalist?

I’m not a medievalist but my work in Renaissance iconography has always depended on research material from earlier times. I had my first course in art history as a senior in high school, Mary Institute, St. Louis, 1942–1943. I majored art history at Washington University, St. Louis, receiving my M.A. (1949) under H.W. Janson, and did graduate work at the Institute of Fine Art, NYU, with Erwin Panofsky and others. I received my PhD on the basis of three related published articles in 1973.

When was your first visit to the Index in Princeton? Where was the Index located then? With whom did you work there? Do you remember anything especially interesting about your visit?

My first visit to the Index was in 1950. For a seminar with Panofsky, I was investigating the sudden appearance of the Infant St. John the Baptist in the Florentine early fifteenth century. The Index was in McCormick Hall. I met Rosalie B. Green and worked with her and Isa Ragusa. I also, by chance, met Professor Morey on that visit. I quickly found that the arrangement of the Index card catalog did not offer simple searching under the Baptist’s name. Learning the biblical structure of the index then helped me broaden the conceptual basis of my project and enriched my results.

In my years of working in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, it was always reassuring to know that the copy of the Index was there for consultation. In the 1980s, when I was a member of the Getty AHIP team, the precedence of the Index was a motivating factor in creating new computer tools for art historical research.

Have you made any great iconographic discoveries related to your research using the Index? Have you used the Index for teaching as well as for research?

I am told that my article on the iconography of the Infant St. John, published in 1955 in The Art Bulletin remains useful up to the present day.

Do you have any observations about the evolution of the Index files and database? Where do you think Index work should go next?

With the appointment of Pamela Patton, the Index has finally hit its stride. Along with its change of name, broadened constituency, and superb technical improvements, the Index is fast becoming a major research center. It seems to me obvious that these advances indicate that the direction The Index of Medieval Art is going is the right one.

This blog post is the ninth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce our student worker Brooke Jurgenson.

What year are you in your Princeton education? What are some of your favorite courses or subjects?

I am a second-year student in the Class of 2026. I intend to declare psychology as my major, but I also love philosophy, literature, and art history. My first year, I really enjoyed the Western Humanities Sequence, which traced the development of the Western intellectual tradition through such foundational works as Augustine’s Confessions and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This semester, I am bridging my interests in psychology and philosophy with the course “The Psychological Foundations of the Mind” and branching out into linguistics by taking “On the Origins and Nature of the English Language.”

What do you do at the Index?

At the Index, I go through different iconographic categories, such as Virgin Mary, Dormition and Christ, Presentation, and add subjects to make the categories more comprehensive and accessible for researchers. For instance, I might add the subject tags “Joseph the Carpenter,” “Anna the Prophetess,” and “Dove” to all the records containing this imagery in scenes of the Presentation of Christ. I also collaborate with the Index research staff on refining the subject taxonomy and applying it more widely to records.

Aside from your experience at the Index, what was the most interesting job or internship you had?

In addition to fostering a love of medieval art at the Index, I have learned much about Princeton’s modern sculpture collection by serving as a Student Art Tour Guide with the Princeton University Art Museum. I lead small group tours around Princeton’s campus, highlighting the subtleties of Henry Moore’s bronze craftsmanship and Jacques Lipchitz’s mysterious abstractions.

What have you learned about medieval art since working for the Index? Has anything surprised you, or does anything stand out as extraordinary or curious about medieval art?

I absolutely love medieval art! Beautiful florals, ornate Latin scripts, gold pigments, and captivating renditions of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child regularly grace my screen. My appreciation for medieval art has grown immensely, and I have come to recognize just how rich and varied the subject area is.

I also never fail to come across the most mysterious and fun “hybrid creatures.” It is only here that I stumble across cats playing hurdy-gurdies and half-dragons slaying monsters. Medieval art truly expands your imagination.

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

This past summer, I took a somewhat impromptu trip to Berlin and visited the Bode Museum. I reveled in the amazing Byzantine collection there. Aside from medieval art, I enjoy Impressionism because of how it captures the ephemeral. My favorite work (as of right now) is Claude Monet’s “View of Vétheuil” painted in 1880, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Accession number 56.135.1).

What’s your favorite building or spot to sit on campus?

When it is warm outside, I love sitting on a bench in the garden behind Maclean House while reading. It is the perfect place to listen to the birds sing and feel the serenity of nature. I also love gazing at the stained glass windows of the Princeton University Chapel, watching the colorful dances of light play out in the sacred space.

Coffee or tea?

I avidly drink both coffee and tea, but I am a tea lover by heart. A steaming cup of freshly brewed green tea is all I need to be content.

NB: This satirical post was shared on April Fool’s Day, 2024.

Although some scholars have claimed to see something like pizza in a wall painting at Pompeii, most historians trace the origins of modern pizza to sixteenth-century Naples. However, researchers at the Index of Medieval Art have discovered previously unrecognized medieval evidence of pizzerias in manuscripts dating at least two centuries earlier.

These early pizza-making scenes depict workers baking crusts, as in the miniature of a fifteenth century Book of Hours (Princeton University Library, MS Garrett 54). Notice how the pizza chef thrusts a long-handled peel with a round crust into a roofed pizza oven. Other steps in the preparation of crust have been identified in the iconography of pizzerias, including a hybrid figure tossing a circle of dough into the air to give the pizza its custom shape. Tossing dough in the air has long been the preferred method in pizza preparation to thin out the crust and give it its signature stretchy, glutinous finish.

Our research found that the toppings for pizza throughout the medieval period would have run the gamut. The typical meats and vegetables that popularly eaten today would have featured on pizza in the Middle Ages, too…with one major exception: the edible berry of the plant Solanum lycopersicum, more correctly identified as the Amoris pomum and commonly called the “the tomato.” Tomato sauce on pizza was strictly prohibited due to the prevalence of the belief that the love apple is the devil’s fruit. But pizza was always a highly customizable dish, and pizza mongers were apt to use any combination of sauces with any number of toppings to suit their palates. Pineapple and anchovies on pesto with casu martzu was a particular favorite among both penitents and unrepentant heretics alike.

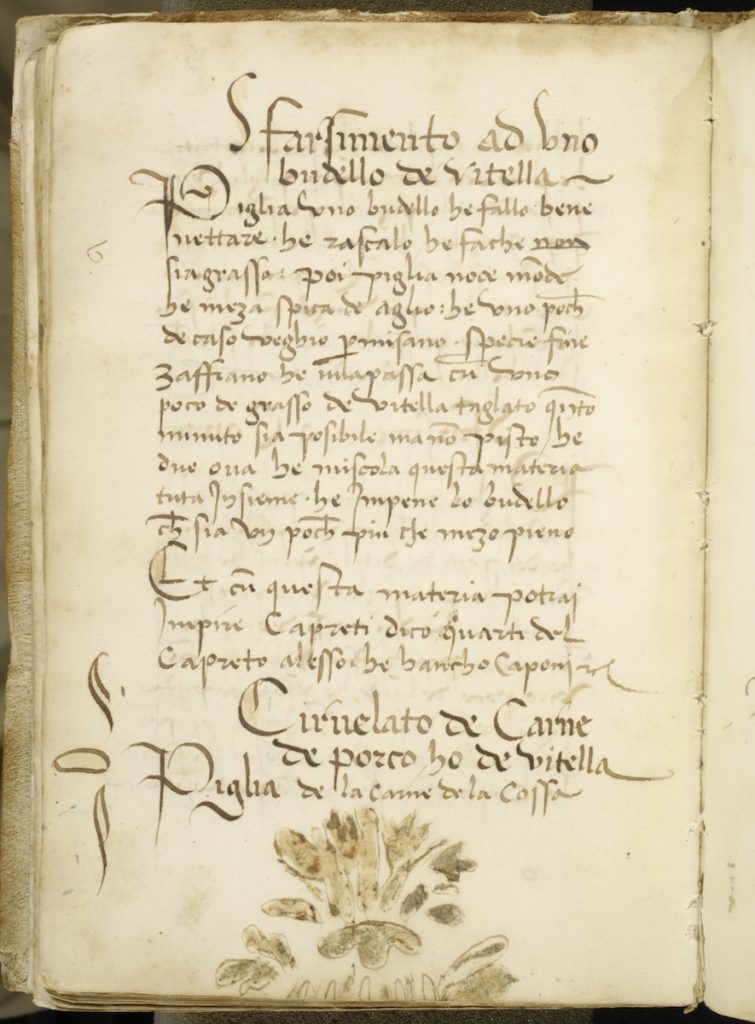

You can imagine our surprise at finding in one late fifteenth-century Neapolitan cookbook, known as the “Cuoco Napoletano,” a recipe for a type of blood sausage known as cervellato (manuscript inscribed “Cirvelato de carne de porco ho di vitelli”) with a mention of its use in pizza preparation. Legendarily, and much like today, sausage was a favorite topping among medieval consumers of pizza, and the following leaf in the cookbook describes such usage in great detail. Or are you a fan of fungi on your pies? Mushrooms too made it onto the menus of pizza chefs, and some illustrations in medieval manuscripts show the fleshy morsels lined up and ready to chop.

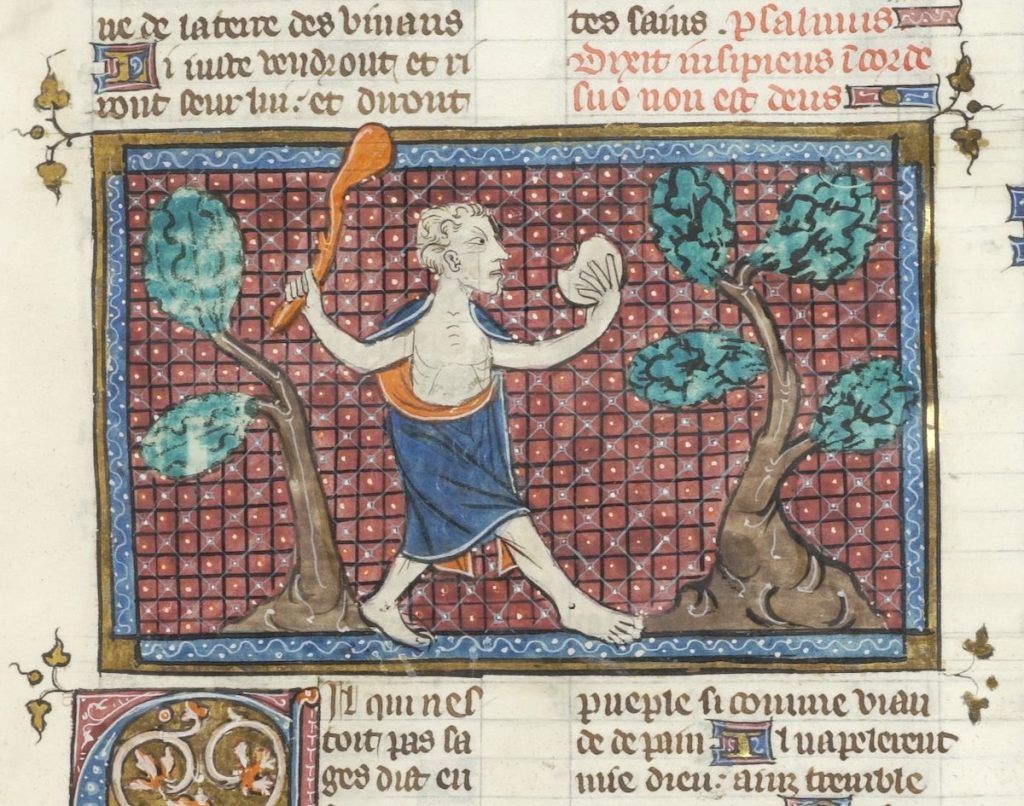

Whether deep-dish or thin with extra cheese, pizza was prized in the Middle Ages. Pizza to go wasn’t out of the ordinary, either, but the pie would have to be fiercely guarded by its consumer. Eating a slice, or “wolfing ’za” as the medieval collegiate vernacular would have it, was often a perilous, two-handed operation. In one medieval image, you’ll notice that a large man chowing down on a delicious slice folded in one hand was required to wield a club with his free hand to ward off would-be pizza poachers!

It was also a seasonal favorite. Such early forms of a pizza would have been regarded as the perfect addition to any menu on the first day of April.

(And by the way, April Fool!)

We are very pleased to announce that Kyriaki Giannouli has joined the Index remotely for a three-month, part-time research opportunity to help incorporate key works on Mount Athos (Greece) into the database!

Kyriaki is a doctoral candidate specializing in Byzantine History at the University of Ioannina and a professional conservator of paintings. Her research focuses on examining the significance of Greek landscapes within the travelogues of Western Holy Land pilgrims from the 12th to the 17th centuries. She is an expert in Byzantine portable icons, frescoes, coins and seals and has hands-on experience in creating specialized conservation reports and working with databases.

At the Index, Kyriaki has started working on enamel and metalwork backfiles and has already made digitally available several objects on Mount Athos, including a fourteenth-century chalice from Vatopedi monastery (Index system number mar20240205001) and an eleventh-century book cover from Lavra monastery (Index system number mar20240212001). Her position requires her to examine the Index legacy records, update the metadata, identify new color images, and incorporate them into the online database. This will allow scholars worldwide, who are not able to travel to use the print Index on the Princeton campus, to access these images and their metadata. We are very excited and grateful to have Kyriaki join us in this collaboration!

This position is part of a multi-year project focusing on Mount Athos-related collections at Princeton (https://athoslegacy.project.princeton.edu/) and has been generously funded by the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies with the support of the Dimitrios and Kalliopi Monoyios Modern Greek Studies Fund and Art & Archaeology Department at Princeton University.

This blog post is the eighth in a series focusing on members of the Index staff. Today we introduce our student worker Tinney Mak.

What year are you in your Princeton education? What are some of your favorite courses or subjects?

I’m a junior right now studying computer science. Some of my favorite classes that I’ve taken are “Everyday Writing in Medieval Egypt” and one where I learned how to read hieroglyphics (fulfilled my childhood dream).

What do you do at the Index?

I mostly deal with tagging subjects on works of art to make sure that people doing research have an easier time finding the materials they want.

Aside from your experience at the Index, what was the most interesting job or internship you have had?

The most interesting internship I’ve had was last summer where I spent eight weeks in Malaysia analyzing a diabetes dataset. I learned a lot from the people I worked with and also really enjoyed exploring the country.

What have you learned about medieval art since working for the Index? Has anything surprised you or does anything stand out as extraordinary or curious about medieval art?

Since working for the Index, I’ve been continually impressed by the amount of skill and knowledge it must take to decipher what’s going on in a piece of art, especially since objects often get extremely worn down through time. It’s always interesting learning about the vast number of different work of art types that I didn’t even know existed (current favorite: croziers!).

Do you have a favorite work of art or favorite place you’ve visited?

My favorite place that I’ve visited is probably Budapest. I remember taking the ferry down the Danube and being in awe of the Liberty Monument on the hill.

What’s your favorite building or spot to sit on campus?

The Mathey common room because of the comfy couches, high ceilings, and occasional piano playing.

Coffee or tea?

Tea! Specifically, a nice cup of Earl Grey.

Modern study of medieval iconography inevitably entails grappling with exceptions and the rupture of expectations. No sooner might scholars settle on an expected visual formula—Cain killing Abel with his farmer’s hoe, Saint George riding his snowy steed—than we’re pulled up by an image that flouts those rules. In the fifteenth-century Alba Bible, Cain sinks his teeth directly into his brother’s neck, arguably in reference to Jewish exegesis, while in some Byzantine and post-Byzantine icons of St. George, a small boy carrying a cup rides with the saint, inspiring a semi-serious modern tradition concerning George’s love of coffee. Other iconographic traditions seem to emerge out of the blue, as did the distinctive type known as the Virgin of Humility, which flowered suddenly in Mediterranean cities in the 1340s. Such unruly iconographies both intrigue and disappoint us: they engage yet disobey our expectations, and we are left to wonder why.

The culprit in such cases is less often a rogue medieval work of art than the rigidity of modern scholarship. Despite ample evidence to the contrary, the assumption that medieval iconographic norms were formulaic, authoritative, and above all universally obeyed still shapes the way modern scholars analyze the imagery they study. Even after the poststructuralist turn, art historians have continued to wrestle with expectations deeply embedded in the discipline: that medieval artists preferred to copy or turn to text rather than to innovate; that unprecedented iconography must be based on a lost original; that patrons or learned advisors must have directed artists’ work; that traditions translated smoothly across media, formats, and contexts; that all viewers read and understood the images they saw in the same way. Underlying many of these assumptions has been a wider one: that the ideas of greatest value must be tracked to artists rooted in cosmopolitan centers, rather than to artists and works of art that circulated freely throughout their peripheries.

The conference “Unruly Iconographies? Examining the Unexpected in Medieval Art” aims to open a new conversation about medieval images that don’t follow the rules. We call for papers, drawn from any area of the medieval world broadly defined, that ask both speakers and audience to rethink the unspoken paradigms that have decided which iconographic motifs are canonical and which are “singular,” “exceptional,” or even “mistakes.” At the broadest level, we seek to problematize the binaries on which these paradigms were founded: tradition versus invention, canon versus exception, and center versus periphery. At a more specific one, we invite deeply researched case studies whose particularities can lead scholars to a more effective, contextually sensitive, and historically informed approach to the study of images and image-making in the Middle Ages.

“Unruly Iconographies?” will take place on November 9, 2024 at the Index of Medieval Art at Princeton University, following the Weitzmann Lecture by Dr. Brigitte Buettner, held on November 8 and hosted by Princeton’s Department of Art & Archaeology. It also will constitute the first of two internationally linked events, the second of which will be a site-based seminar at the Center for the Art and Architectural History of Port Cities “La Capraia” in Naples in June 2025. Whereas the Index conference will consider broadly disciplinary questions about methodology, theory, and models, the Naples conference, hoped to be the first of several site-based conferences of this kind, takes southern Italy as a laboratory for exploring the relationships between iconography and place within a geographically expanded Middle Ages, focusing on the potentials and limits of the study of iconography in southern Italy. Details about this conference will be available in Summer 2024.

Submissions for the Princeton-based conference are invited by April 1, 2024. They should include a one-page abstract and c.v. and be sent to fionab@princeton.edu. Travel and hotel costs for the eight selected speakers will be covered by the Index. Speakers will be informed of their selection no later than May 1, 2024.