“We three kings of Orient are…” runs the traditional Christmas carol. If you were that kid who wondered “Just who are these guys with their weird-sounding gifts? And where’s ‘Orientare’ anyway?” this blog post is for you.

The story of the Magi originated in the Gospel of Matthew (2:1-12), which tells of “wise men from the east” (magi ab oriente) who traveled to Jerusalem seeking the king of the Jews after seeing a star portending his birth. When they reached Bethlehem, Matthew recounts, they fell and adored him, offering gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Although this fairly skeletal story offers few details about how the magi looked or from where “in the east” they hailed, that didn’t stop medieval artists from developing their Biblical story into an elaborate visual tradition.

Matthew offers no information about the number of magi who made the trip to Bethlehem. The tradition of depicting them as a trio predominated from the third century onward, perhaps inspired by the three gifts mentioned in the biblical account. Nonetheless, early medieval depictions of the magi in other numbers, such as two, four, or even six, can occasionally be found. Matthew also remains silent about the magi’s names; the ones with which we are familiar today—Melchior, Caspar, and Balthazar—appear much later, in Byzantine texts and images of the sixth century. One of the earliest such instances is the Adoration of the Magi mosaic in Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, where the elder, foremost magus is labeled Caspar, rather than Melchior, as more often would be the case in later medieval art.

Despite the lack of information about the locations from which the magi came, artists quickly developed ways of visually emphasizing their foreign origins. Early medieval images drew on traditional Roman representations of non-Roman peoples paying homage to the emperor, depicting the magi in appropriately “outlandish” dress such as the short tunics, brightly patterned leggings, and forward-peaked Phrygian caps that appear at Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo. Artistic interest in signaling the magi’s foreign origins corresponded well with Christian exegeses that interpreted the adoration of the magi as symbolic of “heathen” peoples’ recognition of Christ. It was not until the tenth century in western Europe that the magi were reconceived as royal figures, in association with the reference of Isaiah 60:1-4 to the Messiah’s illumination of Gentiles and kings. In many works of art from this point onward, the magi have traded in their traditional caps and trousers for crowns and royal robes, as in the early fourteenth-century Saligny Hours (Morgan Library & Museum, MS. M.60, fol.8r).

From the early Middle Ages onward, the magi were increasingly conceived to be of different ages and geographical origins. In the eighth century, the unknown Irish author nicknamed the “Pseudo-Bede” set down these ideas in writing, describing the magi as of three ages—youth, maturity, and old age—that corresponded to three stages of the life cycle as described by Classical philosophers. Their representation in the ninth-century Stuttgart Psalter (Würtembergische Landesbibliothek, Bibl. Fol. 23, fol. 84r) observes this tradition, depicting them with a white beard, a dark beard, and no beard at all.

The Pseudo-Bede also described the magi as hailing from the three known parts of the medieval world: Europe, Asia, and Africa. These continents, which formed the basis for the typically tripartite division of medieval T-O maps, were also thought each to have been settled by one of Noah’s three sons, Ham, Shem, and Japeth, with whom medieval thinkers sometimes associated the division of humanity into African, Asian, and European “races.” The late medieval and early modern tradition of representing the magi with ethnic features that European artists tended to associate with each continent—Melchior as a white European, Caspar with Asian features, and Balthazar as a black African—can be traced to this chain of ideas. The opportunity to distinguish the magi as exotic foreigners through their physical appearance as well as through costume and other attributes inspired some of the most elaborate and imaginative portrayals of the later Middle Ages, among them Hieronymous Bosch’s famous 1510 Adoration of the Magi in the Prado Museum. In the Index, many similar images can be found by browsing the subject “Black Magus.”

Extensive image cycles developed around the story of the magi; these illustrate the several stages of their journey, including their questioning of Herod, their sighting of the star, and their arrival in Bethlehem, as well as the dream in which they are warned to avoid Herod and their journey homeward by another route. Over a dozen of these subjects, from “Magi, Adoration” to “Magi, Vision of Christ at Different Ages,” are catalogued in the Index. The most popular subject of all, for medieval and modern viewers alike, is the Adoration of the Magi, depicting the moment when the wise men render homage to the Christ Child in Bethlehem. Portrayals of this event range in both complexity and mood, from the charming, trousered travelers of early Christian tradition to the theatrical processions, replete with angels, gaily costumed servants, and trains of exotic animals (including camels!), of late medieval works like Gentile da Fabriano’s 1423 altarpiece of the Adoration, now in the Uffizi Gallery. Although we still have no idea where these wise guys came from, their presence never fails to bring magic and mystery to the traditional Christmas story.

Someone made each of the works of art described in the Index of Medieval Art, and since the beginning of its online database, The Index has acknowledged the individuals and workshops responsible for generating illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, mosaics, et al. when their identities are known. In the original Index system, artists and scribes each occupied a separate field, however, in the updated Index a new field has been established to incorporate both roles under the title of Creator. This reflects the fact that in some media, such as manuscript illumination, the roles of scribe and artist were not always separate: at times one individual undertook both kinds of work, while in other cases the jobs were more specialized.

The Index here expresses a caveat: Creator will not appear on every record. Medieval artists and scribes were/are largely anonymous, creating unsigned works of art for patrons who were also frequently unknown. However, some of the approximately 1400 creators who are named in the Index are known because they signed their works. Others were acknowledged by patrons who named artisans in their inventories, and still others have been identified by modern art historians who have spotted enough similarities among groups of works to assign a nickname for their otherwise anonymous master.

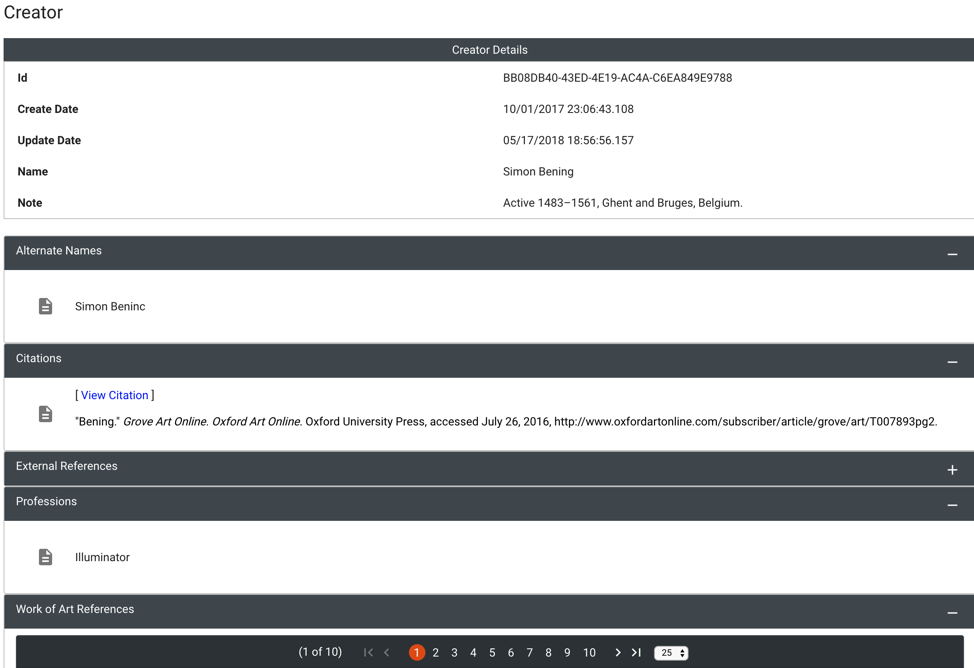

You can learn more about the artist associated with a particular work of art by looking at the work of art record, where the Creator field is located just toward the bottom. In the example below, a screen shot of a manuscript main record shows the name of Simon Bening as creator.

Click on the name, and another window will open providing information about the creator, including such information as general notes, alternate names, bibliographical citations, profession/s and work of art references. This last bit of information presents a list of all works of art associated by the Index with the artist. In the case of our example Simon Bening, this includes some 250 manuscript folios attributed to the artist and included in our database. The researcher can then click through the records to view these works.

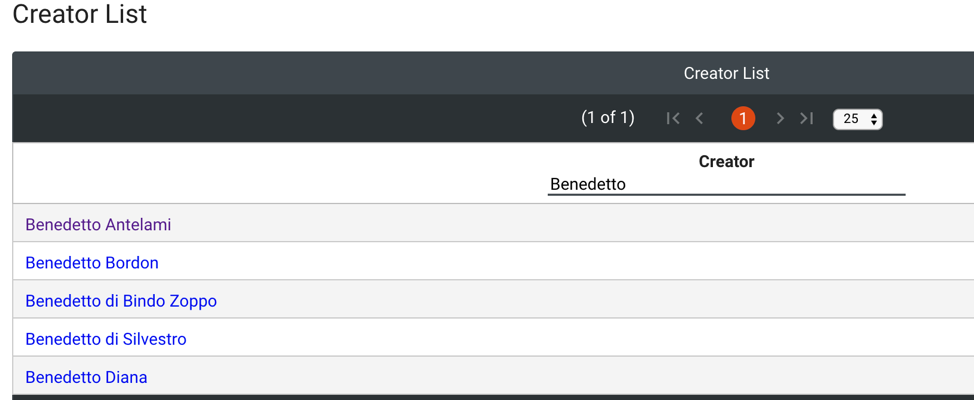

You can also browse by Creator name to see the information and records that the Index includes for a particular Creator. Choose the Browse option on the home page, and from the Browse Indices, click on Creator to open an alphabetical list of names. To find the artist or scribe of interest, either scroll through the list or type the desired name on the line below “Creator” at the top of the list. Click on the correct name, and a window will open as above.

The information about artists and scribes is intended to provide a springboard for further research. Citations frequently include an article in Oxford Art Online, many of which are followed in turn by relevant bibliography.

Although as noted, most medieval artists and scribes are unknown, The Index does include nearly 1400 “named” creators. A significant portion remain personally anonymous, but have been given monikers based on the attribution of works of very similar style or other details, such as the Gold Scrolls Group, named for a distinctive style of ornament, or the Master of Catherine of Cleves, a name based on work created for a specific patron. Searching Grove Art Online for “Anonymous Masters” will yield page after page of unknown creators whose works have been linked in this way to create a body of work by one artist, scribe or workshop. Because many of these names are still in use in art historical scholarship, the Index includes them in the Creator list, sometimes designating them as “see from” terms when consensus about authorship is not clear. We love to keep our records updated, so if you know of new research about the attribution of a work of art, please bring it to our attention at theindex@princeton.edu.

Judith K. Golden

Registration for the Symposium “Eclecticism at the Edges: Medieval Art and Architecture at the Crossroads of the Latin, Greek, and Slavic Cultural Spheres” is now open. The Symposium will be held on April 5-6, 2019 in 106 McCormick Hall on the Princeton University campus. This event is free, but registration is required to guarantee seating.

For details about the Symposium, please check the event web page at https://ima.princeton.edu/conferences/

We look forward to seeing you!