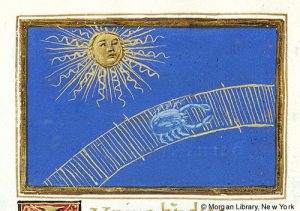

On June 21st we recognize Cancer, the astrological sign that Richard Hinckley Allen called the most “inconspicuous figure of the zodiac” (Allen, 107). Representing the sun at its highest point, Cancer is the zodiacal sign of the summer solstice. In ancient Egypt, the Cancer sign was imagined as a scarab beetle, and in Mesopotamia as a turtle or tortoise, both of which may have pushed the sun across the heavens. In Europe, traditionally, the constellation of Cancer was identified with the crab from Greek mythology that was crushed by the foot of Hercules and placed in the sky by Hera. Some have speculated that the characteristic sideways walk of hard-shelled crustaceans, whether crayfish or crab, could be symbolic of the backward shift in day-length after the arrival of the summer constellation in the Northern Hemisphere at the end of June, and Medieval people also believed those born under Cancer’s influence harnessed great, gripping power.

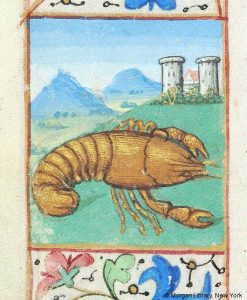

At the Index of Christian Art, the label “lobster-like” has been used to describe Cancerian crabs that are not at all “crab-like.” These crustaceans have elongated pincers, chunky claws, and a distinct tail, and they more closely resemble a lobster or a crayfish. The zoological treatise The Crustacea, published by Brill in 2004, states that, although crabs are the most frequent symbol of the Cancer sign, that the variety of shellfish that adorn horoscopes “can bring surprises” (Forest et al., 173). It is possible that while the symbol of Cancer may draw from a singular iconographic entity which included all shellfish, the idea of a distinct crab, including its spoken and written labels, could be historically transmutable. A definitive explanation for the choice of crustacean in horoscopes might be impossible, but there are some hints as to why “lobster-like” crabs were so pervasive in zodiacal art of the medieval period.

“Cancer,” “Crab,” & “Crayfish”

“Cancer” is an ancient word of Indo-European origin from a root meaning “to scratch.” Today Cancer is the scientific Latin genus name for “crab,” but in classical usage it described many species of shellfish. J.-Ö. Swahn notes in “The Cultural History of Crayfish” that in both Sanskrit and Greek the word for crab had the same meaning as crayfish, both animals having pincers. While the Latin word for Cancer, Carcinus, comes from the Greek karkinos, the English word “crab” has Germanic and Old English roots, and an Anglo-Saxon chronicle from about the year 1000 identified Cancer as crabba (Allen 107). In Old High German (800-1050), kerbiz meant simply “edible crustacean” and was also used to describe crayfish. The OED links the Middle High German (1050-1350) krebz to the Middle French (ca. 1400-1600) escrevisse, which in turn became écrevisse (crayfish).

The OED cites these words for crayfish, through much of their history, were general terms for all larger edible crustaceans. On “lobster,” OED notes some crayfish are called “fresh-water lobsters” and the term “lobster” is applied to several crustaceans of resemblance. Well into the seventeenth century, the word “cancer” and its translations were used as generic terms for all crabs and “lobster-like” creatures until Linnaeus established the species name Astacus Astacus for crayfish in his Systema Naturae of 1758 (interestingly, also with the synonym Cancer Astacus). The OED also noting that the 1656 translation of Comenius’ Latinae Linguae Janua Reserata, described the crayfish as a “shelled swimmer, with ten feet, and two claws: among which are huge Lobsters of three cubits; round Crabs; Craw-fish, little Lobsters.” So, etymologically speaking, crabs, crayfishes, and lobsters were mingled together from very early on.

Star Sign and Sustenance

In the Middle Ages, the zodiacal symbol of Cancer often appeared in the calendar pages of devotional books, or on adorned monumental sculpture of the Middle Ages. The Index records examples in these mediums (including examples on more than 200 manuscript pages) with the subject heading Zodiac Sign: Cancer. Generally, the depiction of the sign of Cancer as a crab is most prevalent in art from the Mediterranean and Western Europe, possibly due to the proximity to the sea, but the crayfish as a symbol for Cancer is not unusual, even in coastal regions. Crabs are saltwater decapods, creatures with ten feet or five pairs of legs. Crayfish are also decapods, but they thrive in freshwater lakes and rivers. Summer was the best season for fishing, and crayfish were easily trapped along the streams and creeks of rural Europe. The French and the English were the first to incorporate crayfish into their diet.

The Romans had viewed the crayfish as a scavenger animal, and they disliked the taste in their cuisine. Elevated from its lowly status as mere fodder in the classical era, crayfish came to be considered a delicacy in Western Europe from as early as the tenth century. In medicine, the sign ruled over the chest, stomach and ribs, and there are also several medieval pharmacological texts that note the medical properties of the crayfish, including the fact that “If you boil them in milk they cause a good sleep” (Swahn, “The Cultural History of Crayfish,” 247). We know that Europeans were using crayfish in their recipes and tinctures, so their distinctive form would have been a familiar one.

Sources

Allen, Richard Hinckley, Star-names and Their Meanings (New York, Leipzig: G.E. Stechert, 1899), 107-111.

Fischof, Iris, “The Twelve Signs,” in Written in the Stars: Art and Symbolism of the Zodiac (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 2001), 111.

Forest, Jacques, J. C. von Vaupel Klein, and J. Chaigneau, The Crustacea: Treatise on zoology – anatomy, taxonomy, biology: Revised and updated from the Traité de zoologie (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 173.

Larkin, Deirdre, “Making Hay: The Zodiacal Sign of Cancer,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Blog, June 5, 2009, http://blog.metmuseum.org/cloistersgardens/2009/06/05/making-hay/060509_bottom/

Swahn, J.-Ö, “The Cultural History of Crayfish,” Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture 372-373 (2004): 243-251.

Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Cancer,” “Crab,” “Crayfish,” “Lobster,” accessed June 2016, http://www.oed.com/.

“Summer and Crayfish,” The Medieval Histories Blog, June 15, 2016, http://www.medievalhistories.com/summer-and-crayfish/.

Reminiscences of Summer Holidays in France

To welcome summer, the Index of Christian Art presents an exhibit of travel ephemera from various cities in France. This selection of guidebooks and maps from the Index archive was inspired by a summer road trip to some of our favorite destinations, including Amiens, Tours, Bourges, Strasbourg, Beauvais, Dieppe, Toulouse, Chantilly, Beaune, Aigues-Morte, and NÎmes. Marked with the pencil signature of Rosalie Green, Index director from 1951 to 1982, many of these guidebooks and maps seem to have been used by Indexers researching cities with important monuments and museums relevant to the mission of the Index.

Guidebook of Chartres, “its Cathedral and Monuments,” by Alexandre Clerval (1859-1918) published in Chartres in 1926. Alexandre Clerval was a Chartrian priest who first wrote an important doctoral thesis on the School of Chartres in 1895.

Preserved in their original printed wrappers, these guidebooks provided details about places of interest to tourists and scholars alike. Perhaps Indexers used these very maps and books to plan an itinerary of sights and sites in all these cities. Mostly in French, and retaining period advertisements, the material here dates from the 1920s through 40s. The unfolded map of Strasbourg is from a Rapide-Plan printed by J. Finck in 1946. Although intended to accompany a traveler on the go, these pocket-sized guidebooks are also treasured by anyone who enjoys armchair travel to distant shores or a lazy summer day lost in remembrance of things past.

The Index of Christian Art presents three images in honor of the 160,000 allied troops who landed on the fortified beaches of Normandy on 6 June 1944. The first, a detail of the Bayeux Embroidery portraying Duke William of Normandy sailing to England, evokes the seaborne operation that marked the beginning of the liberation of occupied Europe from Nazi control. The second, a sculpted personification of Fortitude holding a sword and shield from the west façade of Notre-Dame of Paris, speaks to the courage and resilience of the allied forces in the face of the enemy. The third, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s languid depiction of Peace from the Allegory of Good Government fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, alludes to the aftermath of the war, while also expressing hope for the resolution of current conflicts worldwide.