The year 2020, with its global pandemic, successive environmental crises, and sharp social and political divisions, has tested the patience, faith, and/or equilibrium of many people. As we approach the winter holidays, some will find solace in practicing gratitude—for challenges overcome, for crises averted, or simply for the love and support of those around them. It was not so different in the Middle Ages, when people in difficult circumstances also sought opportunities to consider or express gratitude, sometimes by pondering longstanding exemplars and sometimes by offering thanks of their own. Many of these left traces in medieval visual culture.

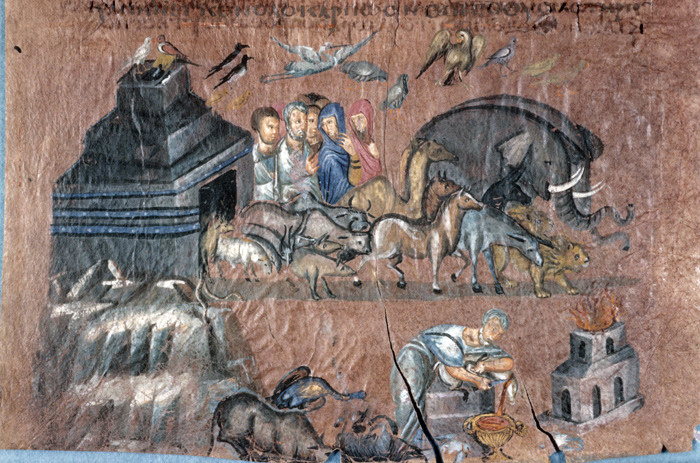

The most widely known medieval images of thanks-giving are those directed to the divine and holy figures to whom the faithful turned in troubled times. An example is the offering made by Noah after surviving the Great Flood, as described in Genesis 8:20 and represented in such works as the sixth-century Vienna Genesis [1]. In this purple-dyed luxury manuscript, the offering scene appears below a short parade of humans and animals, including elephants, lions, and camels, that issues from the ark onto dry land. Noah hunches gently over a sacrificial lamb he has placed on an altar as a thank-offering for humanity’s second chance.

A more creative expression of thanks appears in the Golden Haggadah [2], a fourteenth-century Passover manuscript in which Aaron’s sister Miriam leads the women of the Israelites in music-making and dance to thank the Lord for bringing them safely out of Egypt (Ex. 15:20–21).

Medieval Christians often gave visual thanks to the saints on behalf of those whom they were thought to have healed or rescued from danger. A thirteenth-century stained glass window in Canterbury cathedral records a number of miraculous cures performed by the relics of Saint Thomas Beckett, depicting the relieved victims of an arrow wound, malaria, madness, and even a nosebleed kneeling before the saint’s altar, their hands joined in thanks [3].

In the later Middle Ages, the Virgin Mary, thought to be the intercessor closest to God, earned special gratitude for her protection of the faithful: in the Cantigas de Santa María, the devotees who thank her for her miracles on behalf of the ill, the injured, and the unfortunate include the owner of an ailing silkworm colony, the recovery of which she celebrates by producing a beautiful silk textile that is presented to the Virgin by the king [4].

At times it was the work of art itself that embodied thanks offered to a holy helper. An intriguing example is a mid-sixth-century silver processional cross from Divirigi, now in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, which bears an inscription in Armenian that has been translated “In gratitude … [missing text] … offers to their intercessor St. George (of) Caginkom” [5]. Although the name of the patron is now lost and the reason for their offering remains unstated, the economic value of this substantial silver object suggests the depth of the unknown donor’s gratitude.

Creators and patrons sometimes added their thanks for the successful completion of a work of art. In an eleventh-century French manuscript of the poetic collection De sobrietate (Leiden, Universiteitsbib. BBL 190, fol. 16v), the poet Milo of Saint-Amand kneels before a church from which the hand of God issues in blessing; an inscription above reads “POETA GRA(TIA)S AGIT DEO PRO EXPLETO OPERE SUO” (The poet thanks God for the completion of his works) [6].

In the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the mihrab added to the structure in the 960s is framed by blue and gold mosaic inscriptions in Arabic that thank God for the successful expansion of the building to accommodate the faithful [7].

The belief that all good things come from God threads strongly through medieval visual culture. Nonetheless, some works record expressions of thanks between mortals—even if often these are legendary. An early sixteenth century tapestry from the Netherlands, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, depicts the story of Perseus and Andromeda in a series of scenes reading right to left [8]. While the climax of the narrative is Perseus’ slaying of the dragon that threatened the princess and her land, the sequence ends with the marriage of Andromeda to Perseus in thanks for his heroic deed, an arrangement for which the young couple appears to be, well, grateful.

The staff of the Index hope that the season finds our readers safe, in good health, and with something to give thanks for.

If you celebrate Thanksgiving in the United States, decorations for the feast might well include a representation of a cornucopia, a literal “horn of plenty” (Latin cornu + copiae) spilling over with fruits, vegetables, and flowers suggestive of a generous harvest. Wondering where this symbol came from and how it got onto Aunt Marian’s Thanksgiving table? Wonder no more: armed with 139 online records for the subject “cornucopia,” the Index is here to help.

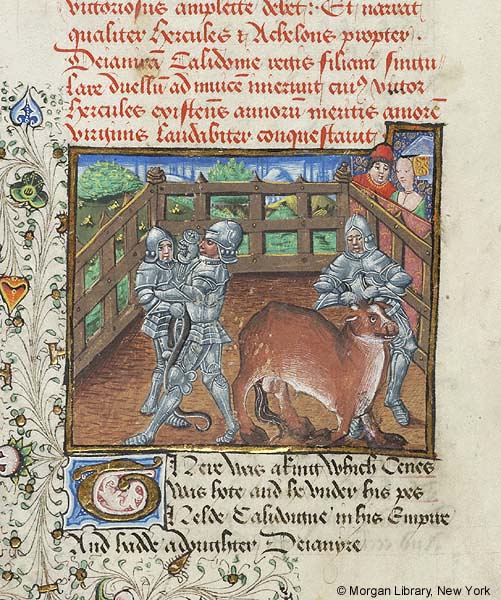

The cornucopia originated in classical mythology, where it bore connotations of plenty and good fortune. Explanations of its origins vary: according to Ovid’s Metamorphoses (ix.8), the Greek demigod Herakles tore the horn from the head of the shapeshifting river god Achelous, whom he wrestled to win the hand of Achelous’s daughter Deianira. Heracles then gave it to the Naiads, who turned it into a horn that produced an endless supply of foodstuffs. The Index records include an engagingly “modernized” version of this scene in a fifteenth-century manuscript of John Gower’s Confessio Amantis now in the Morgan Library (Fig. 1). Several other ancient sources attribute the horn to the goat Amalthea, which suckled Zeus on Crete when he was hidden there by his mother Rhea from his child-eating father Cronus. When Zeus accidentally broke off one of the goat’s horns, it became imbued with the power to be filled with whatever the owner might desire.

The positive connotations of the cornucopia made it a popular classical attribute. Usually configured as a twisted horn from which fruit, flowers, or other plants emerged, it became associated with a number of deities and personifications, including Demeter, Gaia, Persephone, and Tyche, the Roman Fortuna. A Roman statue of Tyche-Fortuna from the first or second century CE, today restored with the portrait head of an unknown woman (Metropolitan Museum of Art), portrays the goddess holding a ship’s rudder, alluding to how fortune steers human fate, in her right hand and a cornucopia filled with fruit in her left (Fig. 2).

A rendering of Fortuna with these attributes also can be found in a fresco from the synagogue of Dura Europos, produced by 244 CE (National Museum of Damascus). One of many classical references found in these early Jewish wall paintings, it appears as a faint line drawing on the right lower panel of the central door (Fig 3). In both these cases, the overflowing horn suggests a hope for the abundance that comes from good fortune.

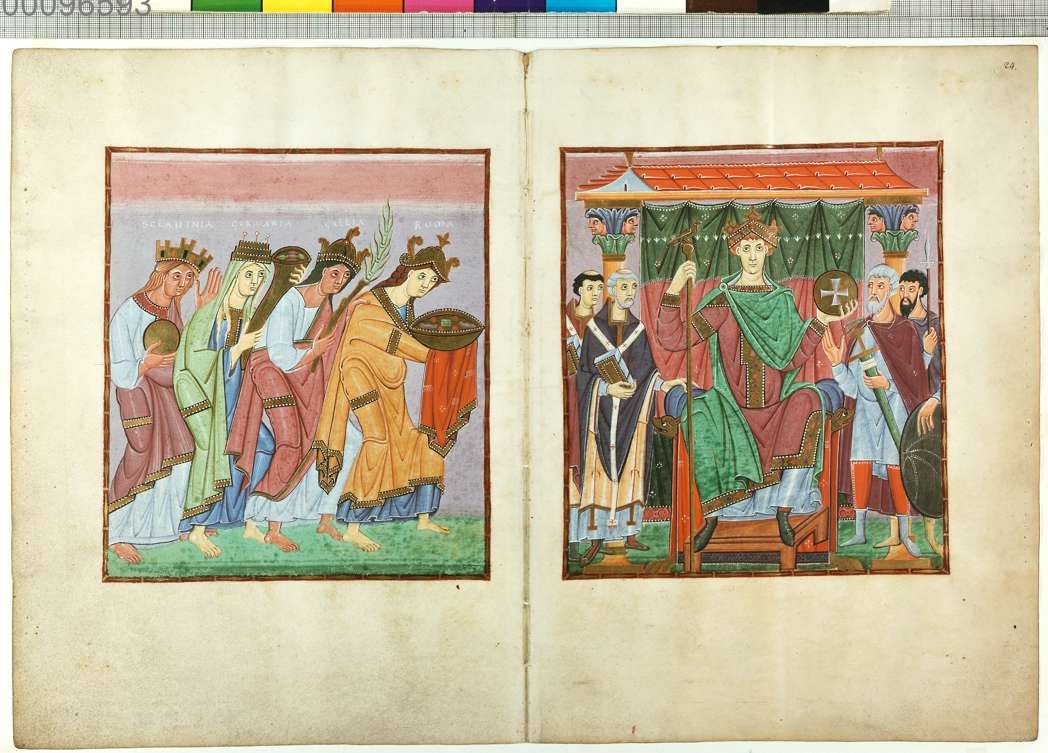

During the Middle Ages, the symbolic associations of the cornucopia expanded significantly. While it could continue to promise good fortune, it also appeared as a sign of homage, as in the Gospels of Otto III, produced in the Holy Roman Empire around the year 1000 (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek). Here, the four personified provinces who bring tribute to the emperor include a personification of Germania holding a golden cornucopia (Fig. 4); although no fruits are visible, its implications of earthly abundance would have made it an appropriate offering for the imperial ruler.

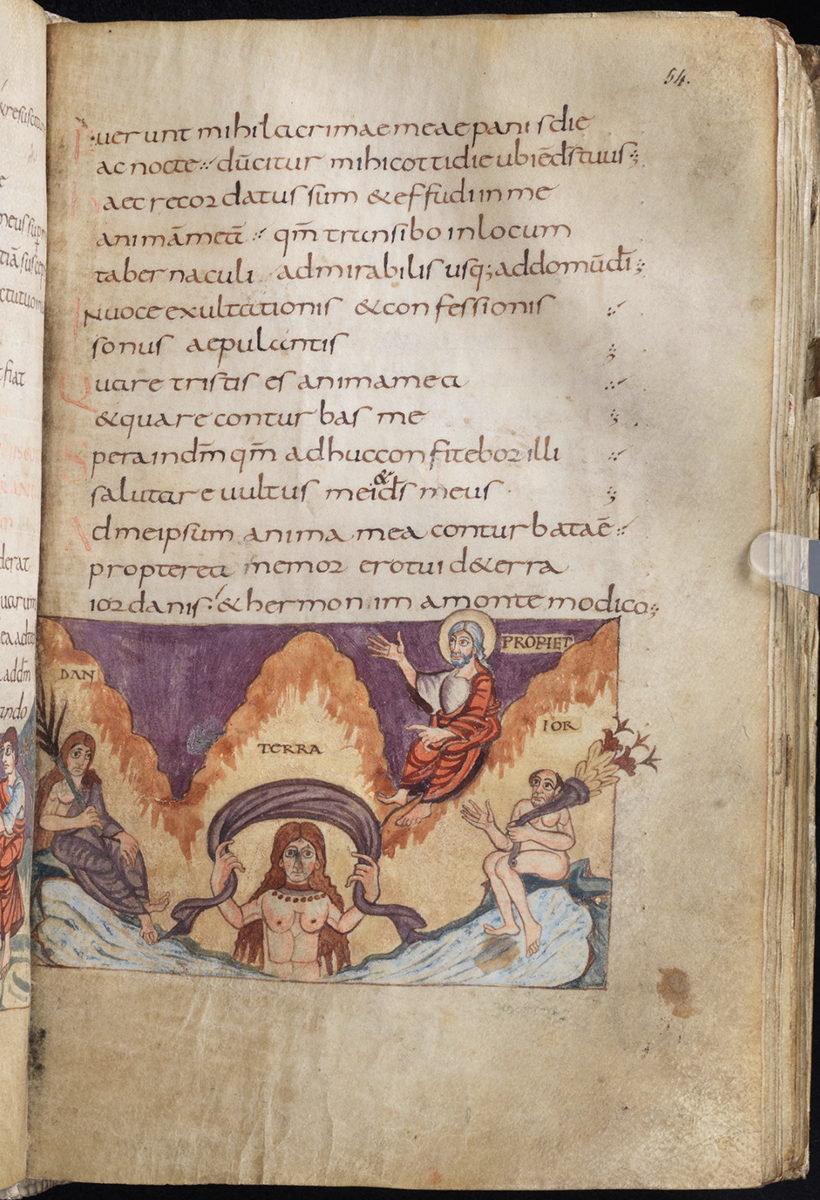

The cornucopia can also be found as an attribute of personified geographical locations, such as cities or waterways. On the right-hand leaf of a fifth-century diptych representing the cities of Rome and Constantinople (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), the figure representing the Byzantine capital holds a large cornucopia in her left hand (Fig. 5); in the Stuttgart Psalter (Württemburgische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart), the personified river Jordan holds a cornucopia sprouting leaves and flowers (Fig. 6).

The cornucopia could also represent more abstract values, including charity, hope, and abundance itself. The portrayal of Abundantia as a lesser goddess who holds a cornucopia originated in Roman tradition, and it persisted throughout the Middle Ages as a secular personification with very similar iconography.

In the early modern era, the formula was further popularized by artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, whose majestic red-robed Abundantia, painted circa 1630, spills an array of apples, grapes, figs, and other fall fruits from a cornucopia to the ground, to the delight of the putti who scramble for them at her feet (Fig. 7). This may be the formulation of the horn of plenty most familiar to modern viewers, for whom a cornucopia centerpiece suggests both the gratitude for good fortune and the spirit of generosity that both stand at the core of the modern Thanksgiving holiday.