Shepherd at the Nativity. Fourth century sarcophagus. Arles, Musée de l’Arles et de la Provence Antique, FAN.92.00.2517. Index system number 000107697.

Of all the medieval images associated with the Christmas story, surely most familiar is that of the Nativity, which depicts the Christ child in the lowly stable of his birth, almost always attended by the Virgin Mary, her husband Joseph, and the ubiquitous ox and ass. Medieval nativity scenes often included other onlookers as well, from the shepherds and magi to whom angels announced Jesus’ birth to the midwives who, in some accounts, assisted at it. Of all these figures, few have a longer or more engaging history than the shepherds, with whose homespun character and simple faith many ordinary medieval Christians could identify.

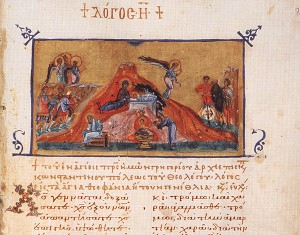

Shepherds and Magi at the Nativity. Homilies of Gregory Nazianzen, 11th century. Jerusalem: Greek Patriarchal Library, MS Taphou 14, fol. 80r. Index system number 150818

The shepherds themselves have biblical origins: Luke 2:8-20 describes them receiving news of Christ’s birth from a host of angels, then rushing to the stable to see the child for themselves. The scene of the angelic annunciation to the shepherds is sometimes presented adjacent to or in the background of the Nativity, and in the very late Middle Ages, under the influence of Franciscan piety, it was also depicted as an independent scene. However, from the beginnings of Christian art, the shepherds were also frequent onlookers at the Nativity itself. By the fourth century, Roman and Gallic sarcophagi had begun to include one or two shepherds standing beside the manger, often raising a hand in recognition of Jesus’ divinity; middle Byzantine mosaics often cast the shepherds as a trio to balance the three magi who also attended the child. Such pairings were encouraged by medieval texts that presented the shepherds as symbolizing the Jewish tradition from which Christianity had sprung and the magi as representing those pagans who converted to the faith. Alternatively, the magi and shepherds were sometimes presented as demonstrating Christ’s recognition by all walks of life, a universalistic message sometimes developed further in the portrayal of both groups as men of varying ages and even ethnicities.

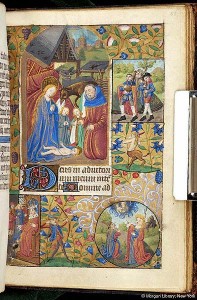

Music-making shepherds on the margin of the Nativity, ca. 1470. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, MS m.32 fol. 51r, Index system number 000175635

Late medieval pietistic trends, which promoted the idea that the poorest of men had been the first to receive news of Christ’s birth as confirmation of the value of humility and simplicity, encouraged fourteenth- and fifteenth-century artists to elaborate their images of the shepherds. They often are shown as rough-hewn peasant types—sometimes even including a shepherdess—who offer the child simple, heartfelt gifts, such as a lamb, a flute, flowers or, more unusually, a basket of eggs. The appeal of these humane, familiar figures still resonates in many a Christmas sermon as well as Christmas carols, from the traditional Austrian “Shepherd’s Carol” to the 1941 pop hit “The Little Drummer Boy.”

Shepherds are noted in over 650 records of the Nativity in the online database of the Index of Christian Art; many more can be found in the card files. Media include sculpture, gold glass, manuscripts, enamel, mosaic, fresco, and painting. We wish all our friends who celebrate Christmas a joyous and peaceful holiday.